An electronic dictionary is a dictionary whose data exists in digital form and can be accessed through a number of different media.[1] Electronic dictionaries can be found in several forms, including software installed on tablet or desktop computers, mobile apps, web applications, and as a built-in function of E-readers. They may be free or require payment.

Information

editMost of the early electronic dictionaries were, in effect, print dictionaries made available in digital form: the content was identical, but the electronic editions provided users with more powerful search functions. But soon the opportunities offered by digital media began to be exploited. Two advantages are that limitations of space (and the need to optimize its use) become less pressing, so additional content can be provided; and the possibility arises of including multimedia content, such as audio pronunciations and video clips.[2][3]

Electronic dictionary databases, especially those included with software dictionaries are often extensive and can contain up to 500,000 headwords and definitions, verb conjugation tables, and a grammar reference section. Bilingual electronic dictionaries and monolingual dictionaries of inflected languages often include an interactive verb conjugator, and are capable of word stemming and lemmatization.

Publishers and developers of electronic dictionaries may offer native content from their own lexicographers, licensed data from print publications, or both, as in the case of Babylon offering premium content from Merriam Webster, and Ultralingua offering additional premium content from Collins, Masson, and Simon & Schuster, and Paragon Software offering original content from Duden, Britannica, Harrap, Merriam-Webster and Oxford.

Writing systems

editAs well as Latin script, electronic dictionaries are also available in logographic and right-to-left scripts, including Arabic, Persian, Chinese, Devanagari, Greek, Hebrew, Japanese, Korean, Cyrillic, and Thai.

Dictionary software

editMany publishers of traditional printed dictionaries such as Langenscheidt, Collins-Reverso, Oxford University Press, Duden, American Heritage, and Hachette, offer their resources for use on desktop and laptop computers. These programs can either be downloaded or purchased on CD-ROM and installed. Other dictionary software is available from specialised electronic dictionary publishers such as iFinger, ABBYY Lingvo, Collins-Ultralingua, Mobile Systems and Paragon Software. Some electronic dictionaries provide an online discussion forum moderated by the software developers and lexicographers[4]

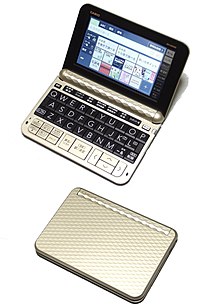

Handheld dictionaries or PEDs

editHandheld electronic dictionaries, also known as "pocket electronic dictionaries" or PEDs, resemble miniature clamshell laptop computers, complete with full keyboards and LCD screens. Because they are intended to be fully portable, the dictionaries are battery-powered and made with durable casing material. Although produced all over the world, handheld dictionaries are especially popular in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, and neighbouring countries, where they are the dictionary of choice for many users learning English as a second language.[5] Some features of handheld dictionaries include stroke order animations, voice output, handwriting recognition, language-learning programs, a calculator, PDA-like organizer functions, time zone and currency converters, and crossword puzzle solvers. Dictionaries that contain data for several languages may have a "jump" or "skip-search" feature that allows users to move between the dictionaries when looking up words, and a reverse translation action that allows further look-ups of words displayed in the results. Many manufacturers produce handheld dictionaries that use licensed dictionary content[6] that use a database such as the Merriam Webster Dictionary and Thesaurus while others may use a proprietary database from their own lexicographers.[7] Users can also add content to their handheld dictionaries with memory cards (both expandable and dedicated), CD-ROM data, and Internet downloads. Manufacturers include AlfaLink, Atree, Besta, Casio, Canon, Instant Dict, Ectaco, Franklin, Iriver, Lingo, Maliang Cyber Technology, Compagnia Lingua Ltd., Nurian, Seiko, and Sharp.

In Japan

editThe market size as of 2014 was about 24.2 billion yen ($227.1 million in May 2016 USD), although the market has been shrinking gradually from 2007[8] because of smartphones and tablet computers. The targeted customer base has been being shifted from business users to students.[9][10] Student models of Japanese handheld dictionaries also include digital versions of textbooks and other study materials. Sony and Seiko have withdrawn from the market.[11][12] As of 2016, Casio had 59.3% of the market share, followed by Sharp with 21.5% and Canon with 19.2%.[13]

In 2016, Seiko announced that their mobile device apps on iPad iOS has been launched.[14]

Dictionaries on mobile devices

editDictionaries of all types are available as apps for smartphones and for tablet computers such as Apple's iPad, the BlackBerry PlayBook and the Motorola Xoom. The needs of translators and language learners are especially well catered for, with apps for bilingual dictionaries for numerous language pairs, and for most of the well-known monolingual learner's dictionaries such as the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English and the Macmillan English Dictionary.

Online dictionaries

editThere are several types of online dictionary,[15] including:

- Aggregator sites, which give access to data licensed from various reference publishers. They typically offer monolingual and bilingual dictionaries, one or more thesauruses, and technical or specialized dictionaries. (e.g. TheFreeDictionary.com, Dictionary.com, Kotobank, and Goo Dictionary)

- 'Premium' dictionaries available on subscription (e.g. Oxford English Dictionary, van Dale, and Kenkyusha Online Dictionary)

- Dictionaries from a single publisher, free to the user and supported by advertising (e.g. Collins Online Dictionary, Duden Online, Larousse bilingual dictionaries, the Macmillan English Dictionary, and the Merriam-Webster Learner's Dictionary)

- Dictionaries available free from non-commercial publishers (often institutions with government funding), such as the Algemeen Nederlands Woordenboek (ANW), and Den Danske Ordbog.[16][17]

Online dictionaries are regularly updated, keeping abreast of language change. Many have additional content, such as blogs and features on new words. Some are collaborative projects, most notably Wiktionary and the Collins Online Dictionary. And some, like the Urban Dictionary, consist of entries (sometimes self-contradictory) supplied by users. Many dictionaries for special purposes, especially for professional and trade terminology, and regional dialects and language variations, are published on the websites of organizations and individual authors. Although they may often be presented in list form without a search function, because of the way in which the information is stored and transmitted, they are nevertheless electronic dictionaries.

Evaluation

editThere are differences in quality of hardware (hand held devices), software (presentation and performance), and dictionary content. Some hand helds are more robustly constructed than others, and the keyboards or touch screen input systems should be physically compared before purchase. The information on the GUI of computer based dictionary software ranges from complex and cluttered, to clear and easy-to-use with user definable preferences including font size and colour.

A major consideration is the quality of the lexical database. Dictionaries intended for collegiate and professional use generally include most or all of the lexical information to be expected in a quality printed dictionary. The content of electronic dictionaries developed in association with leading publishers of printed dictionaries is more reliable that those aimed at the traveler or casual user, while bilingual dictionaries that have not been authored by teams of native speaker lexicographers for each language, will not be suitable for academic work. Some developers opt to have their products evaluated by an independent academic body such as the CALICO.

Another major consideration is that the devices themselves and the dictionaries in them are generally designed for a particular market. As an example, almost all handheld Japanese-English electronic dictionaries are designed for people with native fluency in Japanese who are learning and using English; thus, Japanese words do not generally include furigana pronunciation glosses, since it is assumed that the reader is literate in Japanese (headwords of entries do have pronunciation, however). Further, the primary manner to look up words is by pronunciation, which makes looking up a word with unknown pronunciation difficult (for example, one would need to know that 網羅 "comprehensive" is pronounced もうら, moura to look it up directly). However, Japanese electronic dictionaries (primarily on recent models) include character recognition, so users (native speakers of Japanese or not) can look up words by writing the kanji.

Similar limitations exist in most two or multi-language dictionaries and can be especially crippling when the languages are not written in the same script or alphabet; it's important to find a dictionary optimized for the user's native language.

Integrated technology

editSeveral developers of the systems that drive electronic dictionary software offer API and SDK – Software Development Kit tools for adding various language-based (dictionary, translation, definitions, synonyms, and spell checking and grammar correction) functions to programs, and web services such as the AJAX API used by Google. These applications manipulate language in various ways, providing dictionary/translation features, and sophisticated solutions for semantic search. They are often available as a C++ API, an XML-RPC server, a .NET API, or as a Python API for many operating systems (Mac, Windows, Linux, etc.) and development environments, and can also be used for indexing other kinds of data.[18][19]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Nesi, H., 'Dictionaries in electronic form', in Cowie, A.P. (Ed.), The Oxford History of English Lexicography, Oxford University Press 2009: 458-478

- ^ De Schryver, Gilles-Maurice, ‘Lexicographers’ dreams in the electronic dictionary age’, in International Journal of Lexicography, 16(2), 2003:143-199

- ^ Atkins, S. & Rundell, M. The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography, Oxford University Press 2008: 238-246

- ^ "Forums - Ultralingua". ultralingua.com. 13 March 2013. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ Chen, Yuzhen, 'Dictionary use and EFL learning: a contrastive study of pocket electronic dictionaries and paper dictionaries', in International Journal of Lexicography23 (3), 2010:275-306

- ^ Franklin MWS-1840

- ^ "Ultralingua Inc". ultralingua.com. 18 May 2013.

- ^ "Changes of each year's electronic dictionary shipment" (PDF). Japan Business Machine and Information System Industries Association. 25 Feb 2015.

- ^ "ネットで何でも検索できる時代 電子辞書は生き残れるのか(At era of internet search, how electronic dictionary survives)". 18 Oct 2014.

- ^ "電子辞書、気が付けばカシオの独壇場(Electronic dictionary, suddenly noticed that Casio is leading the market)".

- ^ "ソニー、電子辞書から撤退 (Sony withdraw from electronic dictionary)" (in Japanese). 7 Jul 2006.

- ^ "Notice of Withdrawal from Electronic Dictionary Business". 7 Oct 2014.

- ^ "BCN AWARD for Handheld electronic dictionaries".

- ^ "大学生向け・高校生向けの電子辞書アプリとコンテンツのダウンロード販売を開始(: iOS dictionary apps for university and high school student has been launched and extra contents are available)". Seiko solutions inc. 5 Apr 2016. Retrieved 11 Jun 2016.

- ^ Lew, Robert. ‘Online Dictionaries of English’ in Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. and Henning Bergenholtz (eds.), E-Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography. London/New York: Continuum, 2011: 230-250.

- ^ Tiberius, C. and Niestadt, J. 'The ANW: an online Dutch dictionary', in Dykstra, A. and Schoonheim, T. (eds), Proceedings of the XIV Euralex Congress, Leewarden, 2010: 747-753

- ^ Trap-Jensen, L., 'Access to Multiple Lexical Resources at a Stroke: Integrating Dictionary, Corpus and Wordnet Data', In Sylviane Granger, Magali Paquot (eds.), eLexicography in the 21st Century: New Challenges, New Applications Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2010:295-302

- ^ Semantica S.A.

- ^ Ultralingua Inc.

Media related to Electronic dictionaries at Wikimedia Commons