England Made Me is the debut studio album of English rock band Black Box Recorder. It was released through Chrysalis Records on 20 July 1998. After releasing albums with the Auteurs and as Baader Meinhof, in early 1997, musician Luke Haines formed Black Box Recorder with John Moore and Sarah Nixey. Through most of 1997, the band recorded their debut album with Auteurs collaborator-and-producer Phil Vinall in several London studios, including Milo and The Drugstore. The country folk, easy listening and pop album is named for Graham Greene's 1935 novel eponymous novel, and has been compared to the work of Portishead and Young Marble Giants. Bontempi drums and a radio scanner, and samples are used on several tracks. The songs' lyrics criticize the mundane experience of living and growing up in post-Restoration England, and explore the themes of single mothers and teenage sex.

| England Made Me | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 20 July 1998 | |||

| Recorded | 1997 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 37:16 | |||

| Label | Chrysalis | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Black Box Recorder chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from England Made Me | ||||

| ||||

England Made Me was met with mixed reviews; critics focussed on the album's quality, Nixey's voice and the lyrics. It reached number 110 on the UK Albums Chart. Following an argument between Haines and Moore, which almost saw Black Box Recorder disband, they signed to Chrysalis Records in December 1997. After a brief return to The Auteurs, Black Box Recorder toured the UK in early 1998. "Child Psychology" was released as the album's lead single in May 1998 and reached number 82 in the UK Singles Chart; this was followed by "England Made Me" in July 1998, which peaked at number 89. Black Box Recorder did not tour after the album's release, making a single appearance at that year's Reading Festival. NME included England Made Me on its list of the 50 best releases from 1998, and was reissued as part of a career-spanning box set in 2018.

Background

editBetween 1993 and 1996, vocalist and guitarist Luke Haines released three albums with the Auteurs; New Wave (1993), Now I'm a Cowboy (1994) and After Murder Park (1996). After Murder Park received critical acclaim but was not as commercially successful as its predecessors.[1] For around a year,[2] singer Sarah Nixey had been working as a backing vocalist in the band Balloon to harmonize with frontman Ian Bickerton. Bickerton, who wanted more musicians to help the band in a recording studio, recruited Haines and former the Jesus and Mary Chain member John Moore.[3] In 1996, Haines released a self-titled album under the moniker Baader Meinhof,[1] which Moore enjoyed.[4] Haines had tired of listening to his voice and decided to form Black Box Recorder with Moore in March 1997.[5] Moore coined the band's name while flying home from Spain. Moore persuaded Volume magazine to include a Black Box Recorder track on their next compilation album, prompting Haines to visit Moore at his residence in Little Venice, London, to make noise.[4]

With fruitless results, the Moore and Haines began creating a song with the idea of having Nixey sing; by this point, Haines had written "Girl Singing in the Wreckage" while Moore had written "England Made Me". The pair habitually wrote material without exerting much effort to create simple compositions.[4] Nixey, who had been helping Moore with his own songs, received a fax promising to make her famous if she sang on "Girl Singing in the Wreckage".[2] She had been aware of the Auteurs through friends, and owned a copy of the Jesus and Mary Chain album Psychocandy (1985) but did not know the pair personally.[3] Nixey was unsure about fronting Black Box Recorder but Moore encouraged her by saying he liked her voice. Nixey initially agreed to sing on one track[3] that was due to be released on the Volume compilation. When this release did not occur,[2] the trio planned to make an extended play (EP) and send demos to record labels.[6]

Recording

editBlack Box Recorder went to a basement studio in Camberwell, London, with producer and Auteurs collaborator Phil Vinall, where they recorded "Girl Singing in the Wreckage". Moore was aware of Vinall's earlier work with Haines; he calling Vinall a "somewhat intense individual, and the atmosphere was often dark, bordering on Pinteresque", which he felt was appropriate for their forthcoming album. Hut Records, which had released Haines' earlier work, paid the band an advance fee, allowing them to move sessions to the basement of Milo Studios in Hoxton Square, London. Here, they recorded "New Baby Boom" and "England Made Me", the latter of which was recorded the same day Tony Blair became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Moore said "England Made Me" is "new-slow, new-nightmarish, and new-cruel, but definitely not New Labour". Charlie Inskip, who had worked with Haines, became the band's manager.[4]

Despite the lack of commercial appeal, the songs were attracting interest from potential labels such as Island Records. During the season, the band wrote more material at Moore's and Haines' residences in Camden Town. As they ran out of money for recording, connections through The Jesus and Mary Chain saw sessions moved to that band's studio The Drugstore in Walworth Road. In two three-day sessions they recorded "It's Only the End of the World", "Child Psychology", "I. C. One Female", "Swinging", "Kidnapping an Heiress", "Hated Sunday", "Brutality" and "Jackie 60". Sessions then returned to Milo Studios, where Vinall mixed "Ideal Home"; during a Sunday afternoon, Haines and Moore mooted the idea of recording a cover of "Up Town Top Ranking" (1977) by Althea & Donna. The pair had told Nixey she would not be required for that day's session so she went out clubbing. When they called her to record the cover, she had gone to bed. To persuade her, they told her the session would take only an hour but Nixey said she did not know the words, to which they replied they did not either.[4]

To Haines' surprise, Virgin Records, who owned Hut Records, approved another album from The Auteurs; they recorded four tracks before he continued working on England Made Me.[7] Sessions concluded in autumn with the recording of "Wonderful Life", "Lord Lucan Is Missing" and "Factory Radio" at Milo Studios. The band and Vinall produced most of the tracks except "Ideal Home", which was solely produced by the band. Several engineers worked on the album; Vinall, Martin Jenkins, Teo Miller, Pete Hofmann and the band. Miller mixed most of the songs while Vinall mixed one of them.[8] The cover of "Up Town Top Ranking" ends with a reverb-enhanced crashing sound, which came from Vinall kicking amplifiers. When they remixed the song at On-U Sound Studios, London, the sounds were made louder.[4]

Composition and lyrics

editOverview

editThe music of England Made Me has been described as country folk,[9] easy listening[1] and pop,[10] and recalls the sound of Young Marble Giants.[9] Pitchfork contributor Michael Sandlin said Black Box Recorder deliver a "mildly morose but slightly tongue-in-cheek Sylvia Plath-meets-Paul McCartney pop sensibility" with elements of the work of Portishead.[11] Black Box Recorder worked as a collective in contrast to the Auteurs, of which Haines was the leader.[12] Jason Ferguson of MTV said "wispy samples will waft through the proceedings or the band will get a little carried away and almost start to rock".[13] Moore said Vinall took pride in refining the drum sound on the album and that they used instruments they had accumulated, including Bontempi drums on "It's Only the End of the World", a musical saw, a santoor imported from Iran, and an ex-police radio scanner on "I. C. One Female".[4]

Moore said Black Box Recorder proposed calling the album Mine Camp and Goodbye Beachy Head before landing on England Made Me.[4] The Quietus's Jude Rogers wrote Graham Greene's 1935 novel England Made Me, which explores a "disreputable man wrestling with his conscience", gave the album its title.[14] AllMusic reviewer Stanton Swihart wrote the band lambasted life in England, the "bland, dull mundaneness of daily living as well as the stale political world", and that the album deals with issues ranging from "teenage sex and single mothers to repressive family life and wife swapping".[10] Sandlin called it an "anti-tribute to the shame, horror and general degradation that must naturally come" with growing up in post-Restoration England.[11]

Tracks

editAccording to Gil Kaufman of MTV, Nixey acts as a character who starts the album by "surviving a plane crash", giving the band their name.[15] "England Made Me" starts with Nixey inflicting pain on insects;[16] for the rest of the song, she stays off boredom by contemplating staging a murder.[17] Moore called it a "paean to Graham Greene and British seediness";[4] Niles Baranowski of Consumable Online said on "New Baby Boom", Nixey equates "teen pregnancy [a]s some sort of bad hair day".[18] Moore said the song is about a ghost pregnancy that involved singer Gary Barlow.[4] "It's Only the End of the World" summarizes disillusionment of people in their 20s at the end of the 20th century[11] while Moore said it is about loss of innocence.[4] "Ideal Home" is a homage to property ownership,[19] and according to Tony Fletcher of MTV, the "pettiness of middle class suburban values".[20]

Sandlin said "Child Psychology" describes a child who is intellectually stunted by irreversible neglect by misguided parents.[11] In the song, Nixey repeats the lyric "Life is unfair / Kill yourself or get over it" in a mantra-like way.[10] Moore said the song was influenced by The Tin Drum (1959) by Günter Grass, "Is That All There Is?" (1969) by Peggy Lee and an Open University-operated psychology course he attended.[4] In a review for NME, journalist Kitty Empire called "Up Town Top Ranking" a "warped attempt to reflect Britain's ethnic diversity (possibly)",[21] while Fletcher said Nixey changed the song from a "boastful feminine going-out anthem into a morning-after lament".[20] Elements of trip hop can be found in its breakbeat and frequent loops.[22] Discussing the cover, Nixey described it as "An English woman who sounds very English when singing / speaking in Jamaican Patois".[23] On "Swinging", Moore said Nixey acted as a Blue Remembered Hills-esque character who persuades boys to jump from a cliff face.[4]

"Kidnapping an Heiress" recounts the kidnapping of Patty Hearst; it is sung from the perspective of the Symbionese Liberation Army[18] and includes a reference to The Angry Brigade.[24] The album concludes with "Hated Sunday", which Empire said evokes the work of Morrissey with "its vista of endless, depthless grey days".[21] Ferguson said the addition of four bonus tracks on the US version aided in "extend[ing] the misery" for longer.[13] One of these is a cover of Terry Jacks' 1974 hit "Seasons in the Sun", on which according to Spin's Joshua Clover, Nixey sounds "as if she's singing the grocery list",[16] while Ink 19 writer Matthew Moyer said the band "pervert [the song] to its most evil and base nature". Moyer also said "Lord Lucan Is Missing" recalls the work of Baader Meinhoff "but with ten times the sugar".[25] Fletcher said it is the album's sole upbeat song, "and that's probably because the central character (a British nobleman who disappeared after a crime spree) is someone other than the singer".[20]

Release and promotion

editNixey lost enthusiasm for working in theatre and was working as a temp across London. She stopped this type of employment a week before the band signed with Chrysalis Records,[3] in December 1997. According to Nixey, A&R representative Gordon Biggins' first words to her asked if she wanted to go solo rather than working with Haines and Moore, who two days earlier had argued and almost disband Black Box Recorder until Nixey mediated between them. The band liked Biggins enough to sign with the label.[4] Between the end of recording England Made Me and its release, the Auteurs recorded How I Learned to Love the Bootboys (1999),[7] which was influenced by the atmospheric nature of England Made Me.[26] In February and March 1998, Black Box Recorder toured the UK.[27]

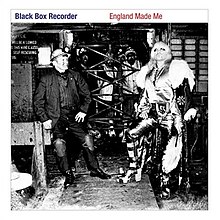

Chrysalis Records released England Made Me on 20 July 1998.[28] The album's cover features a 1973 photograph of wrestler Adrian Street and his miner father taken by Dennis Hutchinson at Beynon's Colliery in Blaina, Wales.[29] Haines said Street, who was cross-dressing, was showing off his championship belt while his father reproachfully stares at him. Haines said he and Moore used to watch wrestling when they were children until it "got axed because it became too pantomime".[30] Hutchinson's photograph is included in Simon Garfield's book The Wrestling (1996); Garfield put the band in contact with Street to ask his permission to use the photograph for the album. Street was enthusiastic about the prospect, hoping the band would sell a million copies of it.[4]

A photograph of the England football team performing a Nazi salute at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin was planned to be used as the album's cover;[31] journalist Owen Hatherley said had the image been used, the album would have "truly encapsulated British fascism by adding sport to the litany of untrustworthy outsiders".[19] The band did not tour to promote the album[32] but they performed at the Reading Festival the following month.[27] The cover of the US version, which Jetset Records issued on 6 July 1999,[33] depicts a girl in a bed who appears "bored and morbidly introspective – [it] tells you most everything you need to know" about the band, according to Sandlin.[11] The US version includes extra tracks "Wonderful Life", "Seasons in the Sun", "Factory Radio" and "Lord Lucan Is Missing";[28] Haines said he struggled to get the album issued in the US due to its highly English nature.[12]

Singles and related releases

editThe release of "Child Psychology" as the lead single from England Made Me was originally planned for April 1998[5] but was postponed to 4 May; "Girl Singing in the Wreckage" and "Seasons in the Sun" were included as B-sides.[28] The video for "Child Psychology", which was directed by Clio Barnard,[34] depicts children in a bath that is located in a forested swamp.[35] "Child Psychology" was banned from MTV and radio stations in the UK due to the lyric "Life is unfair / Kill yourself or get over it".[14] Nixey stated at the time; "I think the line was actually incredibly positive ... We just thought it was tough love really, nothing negative about it".[6] Because the song was released in the US shortly after the Columbine High School massacre, disc jockeys played the chorus backwards to avoid causing offence.[14]

"England Made Me" was released as the album's second single on 6 July 1998. The CD version featured "Factory Radio" and "Child Psychology" as the B-sides,[28] while the seven-inch vinyl edition included a cover of "Lord Lucan Is Missing" (1980) by the Dodgems.[36] The video for "England Made Me", directed by Sonja Phillips,[4] opens with an interior shot of an office building with staff members miming to the song. It cuts to children in a park doing the same, before the band members appear to walk down a street. People outside a farm house are seen miming; it ends with more footage of the band members.[37] To promote the single, the band supported Pulp at their show in Finsbury Park, London and performed at the T in the Park festival.[27]

"Wonderful Life", "Seasons in the Sun", "Factory Radio", "Lord Lucan Is Missing", a remix of Uptown Top Ranking" and the music videos for "Child Psychology" and " England Made Me" were included on the compilation album The Worst of Black Box Recorder (2001).[38] England Made Me was included in the career-spanning Life Is Unfair (2018) CD box set alongside the band's other albums.[4] A vinyl edition of this box set was issued the following year.[39] In 2022, "Child Psychology" became a viral sensation on the video platform TikTok; in addition to this, a one-hour looped version was posted on YouTube. Due to the renewed interest in the track, Chrysalis Records posted an edited version of the track to Spotify.[40] Alexis Petridis, writing for SuperDeluxeEdition, attributed the virality to Billie Eilish posting a video of herself enjoying the track. In 2023, England Made Me was re-pressed on vinyl to coincide with the album's 25th anniversary.[22]

Reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [10] |

| Alternative Press | 3/5[41] |

| NME | 7/10[21] |

| Pitchfork | 6.2/10[11] |

| Q | [42] |

| Rolling Stone | [9] |

| The New Rolling Stone Album Guide | [43] |

| Select | 4/5[44] |

| Spin | 8/10[16] |

| The Village Voice | A−[45] |

Reviews of England Made Me were mixed. According to Swihart, though the album does not immediately appear to be a satirical statement on "anything, but rather an exquisite, even upbeat, bit of pop ... [e]ven when Black Box Recorder do inject a bit of pop cheerfulness into the music, it is seemingly done ironically".[10] Rolling Stone writer James Hunter said Black Box Recorder are "totally of their time, ignoring guitar rock on the one hand and dance music on the other, and insisting on composure and clarity. Along the way, England Made Me gets off on its own erudite kicks".[9] Anna Robinson in The Rough Guide to Rock (2003) called the album a "seductive and perverse listening experience. Sour times wrapped in a sugar coating. Beautiful and change."[1] Clover said; "never once does [Nixey] offer easy emotion; neither does Haines's music let you off the psychological hook with easy melodies".[16] According to Baranowski, the album "isn't without hooks, but musically nothing will catch in your head", except the chorus of "Child Psychology".[18] Ron Hart of CMJ New Music Report said it "provides the perfect soundtrack to those mornings when you're ... wondering what the hell went wrong the night before".[46] Sandlin said at the halfway point, the album slips into "barely-tolerable redundancy" as it loses the "casual, deliberate momentum it'd been building upon".[11]

Some critics commented on Nixey's voice. Hatherley considered England Made Me to be in a "different league entirely" due to the substitution of Haines' "perpetually irritated rasp with the perfect vowels" of Nixey.[24] Empire said Nixey's "opiated debutante tones take Haines' odium to new, discomfiting extremes",[21] while Ferguson called her the band's "secret weapon".[13] According to Moyer, the "innate beauty of Black Box Recorder is that Nixey can sing so sweet and innocently about kidnappings, murder, and the decay of Swinging London".[25] Robert Christgau in The Village Voice said Nixey has a "rich, delicate, contained" voice that is "so neurotic that to expect her to give of herself would be meaningless".[45] Sandlin considered her to have the kind of limited, faint murmur that is "certainly pleasant enough to draw you into her world without hope. But soon, you just feel yourself aching for her to begin screaming her dainty lungs out, just to shake up the melancholic monotony a bit".[11]

Attention was also drawn to the album's lyrics, which critics were mixed on. Swihart said the songs Haines and Moore compose are "cleanly stylized in a way that conceals the raw-nerved lives their characters exist in but are also reflective of the internalization of such relentless barrenness" as the band "seemingly approach their subjects without judgment".[10] Ferguson said the album serves as the "most elegant paean to suicide ever committed to tape. The fact that it's a song-suite almost entirely dedicated to how depressing England is ... you really have to wonder how the trio made it through the studio sessions without any self-inflicted wounds".[13] According to Jamie Kiffel of Lollipop Magazine; "rarely do the lyrics get as specific as their simple singability would imply" as exemplified by "England Made Me". He added the "stories are weird, realistic, and leave plenty of room for your mind to color in the humor with a black marker".[47] Sandlin wrote the band "just keep churning out more quaint songs about resigned depression" and after a while, the listener is "left with empty sorrow and overly reflective gobbledygook".[11] Empire said; "curiously, though, it's the tunes less concerned with dissing Blighty and more preoccupied with escape and revenge that stay with you".[21] Baranowski found it easy to laugh at some of the lyrics, noting Nixey is singing what Haines wrote; in one track Nixey is "pretending to be Haines who is pretending to be a teenaged mother".[18]

England Made Me charted at number 110 on the UK Albums Chart, and "Child Psychology" and "England Made Me" peaked at numbers 82 and 89, respectively, on the UK Singles Chart.[48] NME ranked the album 31st on their list of the year's 50 best releases.[49]

Track listing

editAll songs written by Luke Haines and John Moore, except for where noted.[8]

- "Girl Singing in the Wreckage" – 2:42

- "England Made Me" – 4:00

- "New Baby Boom" – 2:10

- "It's Only the End of the World" – 5:21

- "Ideal Home" – 2:39

- "Child Psychology" – 4:08

- "I. C. One Female" – 2:19

- "Up Town Top Ranking" (Althea Forrest, Donna Reid) – 3:57

- "Swinging" – 3:52

- "Kidnapping an Heiress" – 2:46

- "Hated Sunday" – 3:16

Personnel

editPersonnel per booklet.[8]

|

Black Box Recorder

|

Production and design

|

Charts

edit| Chart (1998) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Albums (OCC)[48] | 110 |

References

editCitations

- ^ a b c d Robinson 2003, p. 48

- ^ a b c Strutt, Anthony (12 March 2003). "Black Box Recorder - Interview". Pennyblackmusic. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Sinclair, Paul (2 July 2018). "Sarah Nixey on Black Box Recorder". SuperDeluxeEdition. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Black Box Recorder (2018). Life Is Unfair (booklet). One Little Indian. TPLP1414CDBOX.

- ^ a b Harrison 1998, p. 9

- ^ a b Redfern 2001–2002, p. 31

- ^ a b The Auteurs (2014). How I Learned to Love the Bootboys (booklet). 3 Loop Music. 3RANGE-30.

- ^ a b c Black Box Recorder (1998). England Made Me (booklet). Chrysalis Records. 7243 4 93907 2 0/493 9072.

- ^ a b c d Hunter 1999, p. 115

- ^ a b c d e f Swihart, Stanton. "England Made Me – Black Box Recorder". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sandlin, Michael (6 July 1999). "Black Box Recorder: England Made Me". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ a b Waters, Christopher (1 February 2000). "Black Box Recorder London Kills Me". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Ferguson, Jason. "Black Box Recorder". MTV. Archived from the original on 14 September 2000. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Jude (1 June 2010). "Uncovering The Ballardian Universe Of Black Box Recorder". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (20 September 1999). "Gay Dad, Black Box Recorder, Dot Allison Introduce Themselves To U.S." MTV. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Clover 1999, p. 194

- ^ Ashare 1999, p. 42

- ^ a b c d Baranowski, Niles (21 September 1999). "Black Box Recorder, England Made Me- Niles Baranowski". Consumable Online. Archived from the original on 30 August 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b Hatherley 2021, p. 24

- ^ a b c Fletcher, Tony (24 September 1999). "Cool Britannia". MTV. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Empire, Kitty (18 July 1998). "Black Box Recorder – England Made Me". NME. Archived from the original on 17 August 2000. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ a b Petridis, Alexis (17 November 2023). "Black Box Recorder / England Made Me". SuperDeluxeEdition. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Lai, Chi Ming (18 July 2011). "Sarah Nixey Interview". Electricityclub. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ a b Hatherley 2021, p. 25

- ^ a b Moyer, Matthew (24 August 1999). "Black Box Recorder England Made Me". Ink 19. ISSN 1075-8933. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Hubbard, Michael (5 July 1999). "The Auteurs – How I Learned To Love The Bootboys". musicOMH. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Gig List". Nude Records. Archived from the original on 28 April 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Discography". Black Box Recorder. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Haines 2011, p. 15

- ^ Alexander (23 September 2006). "Blast from the past 2000: Black Box Recorder". The Portable Infinite. Archived from the original on 17 May 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ Hatherley 2021, pp. 23–4

- ^ "Luke Here for Xmas Cheer". NME. 17 October 1998. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Sansone ed. 1999, p. 38

- ^ Thompson 2000, p. 163

- ^ Chrysalis Records (1 November 2017). Black Box Recorder - Child Psychology (Official Music Video) (video). Archived from the original on 4 May 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ Black Box Recorder (1998). "England Made Me" (sleeve). Chrysalis Records. CHS 5091/7243 8 85713 7 1.

- ^ Chrysalis Records (1 November 2017). Black Box Recorder - England Made Me (Official Music Video) (video). Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ Black Box Recorder (2001). The Worst of Black Box Recorder (sleeve). Jetset Records. TWA40CD.

- ^ Black Box Recorder (2019). Life Is Unfair (sleeve). One Little Indian. TPLP 1414.

- ^ Teo-Blockey, Celine (15 August 2022). "First Issue Revisited: Black Box Recorder on 'The Facts of Life'". Under the Radar. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Black Box Recorder: England Made Me". Alternative Press (134): 92–93. September 1999. ISSN 1065-1667.

- ^ "Black Box Recorder: England Made Me". Q (171): 142. December 2000. ISSN 0955-4955.

- ^ Harris 2004, p. 29

- ^ Wilkinson, Roy (August 1998). "Black Box Recorder: England Made Me". Select (98): 95. ISSN 0959-8367.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (7 March 2000). "Consumer Guide: Cleanup Time". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Hart 1999, p. 26

- ^ Kiffel, Jamie (1 September 1999). "Black Box Recorder". Lollipop Magazine. OCLC 36854274. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ a b Chart Log UK: "Chart Log UK: Darren B – David Byrne". UK Albums Chart. Zobbel.de. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "NME.com". NME. Archived from the original on 17 August 2000. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

Sources

- Ashare, Matt (August 1999). "Reviews". CMJ New Music Monthly. Vol. 72. ISSN 1074-6978. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Clover, Joshua (September 1999). "Black Box Recorder: England Made Me". Spin. 15 (9). ISSN 0886-3032.

- Haines, Luke (2011). Post Everything: Outsider Rock and Roll. London: William Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-434-02009-6.

- Harris, Keith (2004). "The Auteurs". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Harrison, Ian (April 1998). "Ignition – Black Box Recorder". Select (94). ISSN 0959-8367.

- Hart, Ron (5 July 1999). "Reviews". CMJ New Music Report. Vol. 59, no. 625. ISSN 0890-0795. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Hatherley, Owen (2021). Clean Living Under Difficult Circumstances – Finding a Home in the Ruins of Modernism. London: Verso Books. ISBN 9781839762215. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Hunter, James (19 August 1999). "Black Box Recorder: England Made Me". Rolling Stone. ISSN 0035-791X. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Redfern, Mark (December 2001 – February 2002). "Black Box Recorder – A Mellow Crash Landing". Under the Radar. ISSN 1553-2305. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- Robinson, Anna (2003). "The Auteurs/Black Box Recorder". In Buckley, Peter (ed.). The Rough Guide to Rock. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-105-0.

- Sansone, Glen, ed. (28 June 1999). "Upcoming Releases". CMJ New Music Report. Vol. 59, no. 624. ISSN 0890-0795. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Thompson, Dave (2000). Alternative Rock. Third Ear: The Essential Listening Companion. San Francisco, California: Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-607-6.

External links

edit- England Made Me at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)

- Review of "Child Psychology" at The New York Times

- Interview at Spin

- Live review at NME