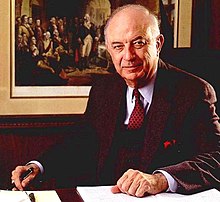

Eugene L. Stewart (February 9, 1920 – August 5, 1998) was an American lawyer and founder of the law firm Stewart and Stewart, an international law firm based in Washington D.C. He was known for his work in international trade law. He was the recipient of numerous awards including the John Carroll Award, an award given to Georgetown University Alumni whose achievements exemplify the ideals and traditions of the university.[2] He is credited with being the leading organizer and founder of the Sursum Corda Cooperative in Washington, D.C.,[4] and was also a former law professor at Georgetown University.[5]

Eugene Stewart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 9, 1920 |

| Died | August 5, 1998[1] |

| Education | Juris Doctor |

| Alma mater | Georgetown Law School[2] |

| Occupation | Lawyer[3] |

| Children | Terence P. Stewart |

| Website | Stewart and Stewart History Page |

Early life and education

editStewart was born in Kansas City in 1920. His father died when Stewart was 14. Stewart then graduated from high school at 16, taking a job with General Motors.[6] He enlisted in the Army-Air Force during World War II where he rose through the ranks, eventually earning the rank of Major.[1] He would use the G.I. Bill to further his education after the war. He would also become a Lieutenant Colonel in the reserves, being the highest-ranking officer among Georgetown University students.[6]

Stewart attended Georgetown University where he graduated in 1948. He went on to law school at Georgetown Law School while also clerking for the United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals. During his time at Georgetown and throughout the remainder of his life, he was active as a Georgetown alumnus, including being the national chairman of the annual giving fund drives and as president of the National Alumni Association.[1][5] Stewart is also credited with helping revive Georgetown University's newspapers The Hoya and The Yard. Stewart graduated from Georgetown Law in 1951 where he would also go on to teach Restitution and Corporate Law.[6]

Career

editStewart began his legal career with the law firm of Steptoe & Johnson in 1951. He worked for the firm for seven years before founding his own law firm.[7] The firm was the predecessor of what would become Stewart and Stewart.[1] Stewart began his own law firm in 1958 with partner David Hume.[7] The law firm was named Hume and Stewart, with Hume leaving the firm in 1962 to run for Governor of Maryland.[8] The firm was named Lincoln and Stewart between 1967 and 1971 with Donald O. Lincoln a partner in the firm. From 1975 to 1978 the firm bore the name Stewart and Ikenson with partner Frederick L. Ikenson. The firm's name was later changed to Stewart and Stewart with Eugene's son Terence Stewart joining the firm. Terence acquired the firm from his father in 1986, which Eugene having an active role in the firm up to his death in 1998.[7]

His work in the 1960s led to the development of new trade policies in the United States, including case law for various trade remedies.[9] During the 1970s, Stewart was involved in countervailing duty cases on flat glass which affected the Trade Agreements Act of 1979 and the availability of judicial review for cases brought under the Act. Stewart was involved in numerous cases involving domestic steel producers in both the 1970s and 1980s. The result of these cases led to changes in U.S. countervailing duty law practices. Throughout his career, he was quoted in numerous books and also gave government testimony on international trade matters.[7]

Sursum Corda Cooperative

editStewart was a leading organizer and founder of the Sursum Corda Cooperative in Washington, D.C.[5][10] In 1965 he was approached as a member of the Georgetown Alumni Association and asked if the association would become involved by sponsoring a low income housing project.[4][6] The idea presented to him was for students and alumni to assist with tutoring the poor and their children in the community. Stewart presented the ideas to the Alumni Board of Governors, but the plan was rejected. He formed Sursum Corda, Inc. and oversaw the construction of the Sursum Corda Cooperative.[6] In 1967, he was awarded the John Carroll Medal from the Alumni Association for his efforts with the project.[6]

Government testimony

editStewart was often requested to provide testimony before various government agencies, specifically on international trade and other matters. For example, Stewart testified before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs in 1968 regarding proposed housing legislation.[11] Senator John Sparkman, chairman of the subcommittee, who presided over the hearing, described it as such: “[T]oday we start hearings on legislation proposing different measures, different proposals on housing and urban affairs for 1968... The legislative proposals we have before us encompass the whole range of housing and urban development programs.”[11] Stewart’s testimony had the purpose of extending Federal housing assistance programs to benefit residents of Sursum Corda. He stated that “My purpose is .... saying that the programs that are now on the books, which programs are extended in the pending legislation and indeed further modified, the 221(d)(3) program, the rent supplement program, and the public housing leasing programs, are sound programs that can be combined by people with a will to create worthwhile housing for low income large families.”[11]

Automotive industry cases

editDuring the 1970s and 80s, Stewart represented the United Auto Workers in some of the largest anti-dumping and safeguards cases in U.S. history. In 1975, Stewart was involved with complaints filed by Congressman John H. Dent concerning imports of new, on-the-highway, four-wheeled, passenger automobiles from Belgium, Canada, France, Italy, Japan, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and West Germany.[12] Over $7 billion of imports were subject to the complaints.[13]

When oil export prices to the United States were sharply increased in 1979, the U.S. automobile industry faced a surge of automobile imports from Japan and other countries. Stewart filed a petition in 1980 for the United Auto Workers, arguing that the U.S. auto industry was being substantially injured by foreign auto imports and sought import relief under Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974. The problems facing the auto industry and its workers were ultimately addressed by a voluntary export restraining agreement with Japan in which the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry agreed to limit the export of automobiles to the United States for a three-year period. Thereafter, Japan voluntarily continued export limits on autos to the U.S. until 1994.[14]

Steel industry cases

editStewart represented domestic steel producers in a series of trade remedy cases that redefined U.S. countervailing duty law practice and that resulted in voluntary export restraint agreements.[15] In 1982, Stewart filed anti-dumping and countervailing duty petitions for a major U.S. producer. These petitions were part of a large number of trade remedy cases brought by three groups of domestic steel producers at the same time. The petitions resulted in 93 preliminary countervailing duty and antidumping investigations involving 9 steel product lines from 9 countries. The petitions were delivered in 494 boxes, contained an estimated 3 million pages and concerned imported carbon steel products with an estimated value of more than $1 billion.[16] The petitions were later withdrawn in 1982 after the United States and the European Community reached an agreement limiting steel imports for three years.[17] The agreement was later expanded in product coverage and extended through September 1989, and subsequently extended through March 1992.

In 1984, Stewart filed a petition on behalf of a U.S. steel producer in conjunction with the United Steelworkers of America who were represented by another law firm. The petition sought temporary import relief from imports of carbon and certain alloy steel products. The petition led to President Reagan negotiating voluntary restraint agreements with the EC and 16 other countries whose exports had increased significantly in recent years, including Japan, Korea, Brazil, Mexico, Spain, Australia, Finland, and South Africa.[18] The agreements which initially limited imports through September 1989 were extended by President Bush for an additional 2½ years through March 1992.[19][20]

Awards and recognition

editStewart was given the John Carroll Medal in 1967 from the Georgetown Alumni Association for his work with the Sursum Corda Cooperative.[6] He was subsequently honored in 1970 by receiving a commendation letter from then President Richard Nixon for his work with Sursum Corda.[21]

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Stewart, Eugene L (72)". The Washington Post. 8 August 1998.

- ^ a b "John Carroll Award Recipients". Georgetown Alumni Online. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ Farnsworth, Clyde H. (13 November 1982). "Specialists Who Thrive on Deficits". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Sursum Corda Lift Up Your Hearts". Journal of Housing. 30 (1). 30 January 1973.

- ^ a b c Feinberg, Lawrence (25 September 1968). "Montgomery Sets Up Study of Gun Control". Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Georgetown's Highest Ranking of The Greatest Generation". The Georgetown Academy. February 1999.

- ^ a b c d "History". The Law Offices of Stewart and Stewart. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Hughes, Harry Roe (2006). My Unexpected Journey: The Autobiography of Governor Harry Roe Hughes. The History Press. ISBN 9781596291171.

- ^ "Clamor Over Cheap Japanese Goods Grows". L.A. Times. PQ Archiver (subscription needed). 12 April 1971. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Monagan, John (1985). Horace – Priest of the Poor. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 9780878404216.

- ^ a b c "Hearings Before The Subcommittee on Housing and Urban Affairs of the Committee on Banking and Currency – Proposed Housing Legislation for 1968". Hearing Transcript. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1968.

- ^ "New, On-the-Highway Four-Wheeled Passenger Automobiles from Belgium, Canada, France, Italy, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and West Germany". USITC Pub 739. September 1975.

- ^ "Twenty-First Annual Report of the President of the United States on the Trade Agreements Program". 1976. p. 44.

- ^ "GATT, Trade Policy Review: Japan". GATT. 1995.

- ^ Kiely, Kathy (1 February 1982). "Imports Hurt, Steel Probe Told". The Pittsburg Press. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ "U.S. International Trade Commission Annual Report". U.S. International Trade Commission. 1982.

- ^ Barringer, William (2000). "Paying The Price For Big Steel". American Institute For International Steel.

- ^ "Operation of the Trade Agreements Program, 41st Report". USITC Pub. September 1990. pp. 153–155.

- ^ "Operation of the Trade Agreements Program, 37th Report". USITC Pub. June 1986. pp. 153–154.

- ^ Protectionism and World Welfare. Cambridge University Press. 1993. ISBN 9780521424899.

- ^ Nixon, Richard (14 September 1970). "Certificate and Letter of Commendation". Retrieved from the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.