Eye-cup is the term describing a specific cup type in ancient Greek pottery, distinguished by pairs of eyes painted on the external surface.

Description

editClassified as kylikes in terms of shape, eye-cups were especially widespread in Athens and Chalkis in the second half of the sixth century BC. The bowl of the eye-cup rests on a short squat foot; both sides are dominated by large painted pairs of eyes under arched eyebrows. The eyeballs are painted in silhouette style, later often filled with white paint or painted white on black. Some eyes are "female", i.e. almond-shaped and without tear-ducts. Often, a stylized nose is placed centrally between the eyes.

While used as a drinking vessel, due to the necessary inclination of the vessel, the cup with its painted eyes, the handles looking like ears and the base of the foot like a mouth, would have resembled a mask. Many of the vases also bear dionysiac imagery.[1] The eyes are assumed to have served an apotropaic (evil-averting) function.[2][3]

Types

editEye-cups were painted by various painters, mostly in the black-figure style, but later also in the red-figure style. The earliest bilingually painted vases, those with both styles, include specimens of eye-cups with a black-figure interior and a red-figure exterior.

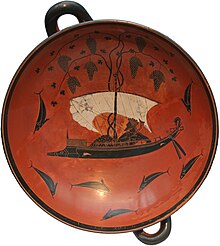

The introduction of this bilingual type and its specific decoration into Attic vase painting is attributed to Exekias. His eye-cup in Munich, dated 530–540 BC, is considered a masterpiece of the type. It depicts Dionysos, lying in a symposiast posture on a ship. His divine nature is indicated by his attributem, a vine, growing from the mast.

Painters or groups

editOther well-known examples of eye-cups are by the following painters or groups:

- Amasis Painter; he painted several eye-cups of a variant shape with non-carinated profile (Type B)[4]

- Andokides[4]

- Antiphon Painter

- Epiktetos: bilingual eye-cups[5]

- Ghost Painter

- Painter of Nicosia Olpe

- Hischylos

- Krokotos Group[4]

- Leafless Group; they continued the basic eye-cup shape with later variants, often lacking the large pair of eyes[6]

- Lydos Group

- Lysippides Painter

- Mastos Painter

- Nikosthenes[4]

- Oltos: bilinguals[5]

- Pheidippos: bilinguals[5]

- Skythes: bilinguals[5]

- Group of Walters 48.42, specialising in frontal views of masks of Dionysos, and of satyrs and maenads between the eyes, and gorgoneia on the cup interior[4]

A special type is the Chalkidian style of cup, of which further variants exist.[7]

History

editDating is often difficult, but the majority of eye-cups were probably produced between 540 and 500 BC, perhaps up to 480 BC.[8] They were also exported to Italy in large quantities. The majority of vases of this type were found as grave goods in Etruscan chamber tombs.

References

edit- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Handorf, in: Klaus Vierneisel, Bert Kaeser (Hrsg.), Kunst der Schale – Kultur des Trinkens, München 1990, p. 419 f.

- ^ Alexandre G. Mitchell (2009). Greek Vase-Painting and the Origins of Visual Humour. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3, 38–44.

- ^ Andrew J. Clark; Maya Elston; Mary Louise Hart (2002). Understanding Greek Vases: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques. Getty Publications. p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e John Boardman, Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, Übers. v. Florian Felten, Mainz 1977, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9, p. 118

- ^ a b c d John Boardman, Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, Übers. v. Florian Felten, Mainz 1977, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9, p. 124

- ^ John Boardman, Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, Übers. v. Florian Felten, Mainz 1977, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9, p. 163

- ^ John Boardman, Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, Übers. v. Florian Felten, Mainz 1977, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9, p. 119

- ^ "Bettina Kratzmüller, Eine attisch schwarzfigurige Augenschale". Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

Bibliography

edit- Corpus vasorum antiquorum. Deutschland. Hrsg. Komm. f. d. Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum b. d. Bay. Akad. d. Wiss. /Union Académique Internationale.Bd 77: München, Antikensammlung Band 13. Attische Augenschalen. Bearb. Fellmann, Berthold. 2004. ISBN 3-406-51960-1

- Friedrich Wilhelm Handorf, in: Klaus Vierneisel, Bert Kaeser (eds.), Kunst der Schale - Kultur des Trinkens, München 1990, p. 418 f.

- Norbert Kunisch: Die Augen der Augenschalen, in: Antike Kunst 33 1990

External links

edit- Kylix: eye–cup (drinking cup), ca. 530 b.c.; black–figure Greek. Obverse and reverse, between eyes: Theseus and the Minotaur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Athenian eyecups of the Late Archaic Period by Andrew Prentice

- Raimund Wünsche, "Trinken aus den Augen" - Griechische Augenschalen, aviso 2005,/4

- A clip showing how these vases resembled a mask (YouTube link)