Fear of Flying is a 1973 novel by Erica Jong. It became controversial for its portrayal of female sexuality, and figured in the development of second-wave feminism.

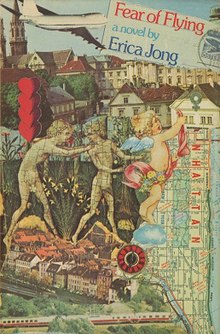

First edition cover | |

| Author | Erica Jong |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Judith Seifer |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Holt, Rinehart and Winston |

Publication date | 1973 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 340 pp |

| ISBN | 0-03-010731-8 |

| OCLC | 618357 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PZ4.J812 Fe PS3560.O56 |

| Followed by | How to Save Your Own Life |

The novel is written in the first person, narrated by its protagonist, Isadora Zelda White Stollerman Wing, a 29-year-old poet who has published two books of poetry. On a trip to Vienna with her second husband, Isadora decides to indulge her sexual fantasies with another man.

The novel's tone may be considered conversational or informal. The story's American narrator is struggling to find her place in the world of academia, feminist scholarship, and in the literary world as a whole. The narrator is a female author of erotic poetry, which she publishes without fully realizing how much attention she will attract from both critics and writers of alarming fan letters.

The book resonated with women who felt stuck in unfulfilling marriages,[1] and it has sold more than 20 million copies worldwide.

Plot

editIsadora Wing is a Jewish journalist from New York City. She and her husband Bennett fly to Vienna for the first psychoanalysts' conference since analysts were driven out during the Holocaust. She associates her fear of flying, both literally and metaphorically referring to a fear of freeing herself from the shackles of traditional male companionship, with recent articles about plane hijackings and terrorist attacks. She also associates fear and loathing with Germany, because she and her husband were stationed in Heidelberg and she struggled both to fit in and to wrestle with the hatred and danger she felt being a Jew in post-Holocaust Germany. Isadora ponders many questions, plans, mental rough drafts and reminiscences as her journey unfolds, including the "zipless fuck," a major motif in the story that haunts the narrator throughout.

Upon arriving, Isadora meets the English Langsian analyst Adrian Goodlove and is immediately smitten. Despite his gruff attitude and poor sexual performance, he seems to provide what she desires but does not find in her own marriage: energy, excitement, desire, danger. They begin a poorly-veiled affair by dancing and kissing rather openly at conference events, staying out nights, and spending days by German pools. Isadora's desperation to feel alive and her developing feelings for Adrian lead her to the toughest decision: to return home with Bennett or to go to London with Adrian. She agonizes over the decision. One night, Bennett finds Adrian and Isadora in bed together and joins them in an adventurous sexual act that Bennett never acknowledges afterward.

Finally, through an emotionally taxing and melodramatic letter that she never delivers to Bennett because he once again walks in and interrupts her, Isadora decides to leave with Adrian. The two of them drive through France, Germany, and Italy camping every night, drinking, and making love. Along the way, Isadora confides in Adrian the stories of her past relationships and first marriage. She reveals that she met her first husband, Brian, in college, where they connected over their mutual love of literature and ability to walk for hours while quoting poetry. They gradually became distant and Brian began to fall into delusions, believing himself to be the second coming of Christ. He became violent, raped Isadora, and choked her close to death in one mental break. He was repeatedly hospitalized and eventually moved to an asylum in Los Angeles in which Brian blamed her for everything, and they finally divorced.

Eventually, Adrian reveals that he has plans to meet his ex-wife and his children, leading Isadora to return home to Bennett. On a train journey to meet him in London, she is approached by an attendant who sexually assaults her, which propels her into her own psychological self-examination.

It wasn’t until I was settled, facing a nice little family group—mother, daddy, baby—that it dawned on me how funny that episode had been. My zipless fuck! My stranger on a train! Here I’d been offered my very own fantasy. The fantasy that had riveted me to the vibrating seat of the train for three years in Heidelberg and instead of turning me on, it had revolted me! Puzzling wasn't it. A tribute to the mysteriousness of the psyche. Or maybe my psyche had begun to change in a way I hadn’t anticipated. There was no longer anything romantic about strangers on trains.

— Erica Jong, Fear of Flying (1973), page 417

She realizes that when she is not in control of her body and does not have agency or autonomy, it does not matter how much she has dreamed of a situation, but it will never be satisfying. When she returns home, she takes a bath; waits for Bennett; and comes to accept her body, herself, and the unknown future: "A nice body. Mine. I decided to keep it" (p. 424).

The zipless fuck

editIt was in this novel that Erica Jong coined the term "zipless fuck", which soon entered the popular lexicon.[2] A "zipless fuck" is defined as a sexual encounter for its own sake, without emotional involvement or commitment or any ulterior motive, between two previously unacquainted persons.

The zipless fuck is absolutely pure. It is free of ulterior motives. There is no power game. The man is not "taking" and the woman is not "giving". No one is attempting to cuckold a husband or humiliate a wife. No one is trying to prove anything or get anything out of anyone. The zipless fuck is the purest thing there is. And it is rarer than the unicorn. And I have never had one.

— Erica Jong, Fear of Flying (1973)

Jong goes on to explain that it is "zipless" because "when you came together, zippers fell away like rose petals, underwear blew off in one breath like dandelion fluff. For the true ultimate zipless A-1 fuck, it was necessary that you never got to know the man very well."

Feminist influences then and now

editFear of Flying was written in the throes of the Sexual Revolution of the 1970s, as associated with second-wave feminism. Finally, it was acknowledged that desire and fantasy are good things and not entirely condemnable in women, and Jong wanted to harness that newfound respect for desire into a piece of art that brought the intersections of sexual and nonsexual life together, which she felt was missing in literature. "At the time I wrote Fear of Flying, there was not a book that said women are romantic, women are intellectual, women are sexual—and brought all those things together."[3] "What [Isadora is] looking for is how to be a whole human being, a body and a mind, and that is what women were newly aware they needed in 1973."[4] However, she also points out the drawbacks of a sexually liberated life and acknowledges that sexuality "is not the cure for every restlessness." Male critics who interpreted Isadora as being "promiscuous" were actually misinterpreting her acts since she has an active fantasy life but does not really sleep with many men. This does, however, allude to the possibility that other charming men can bring a women's fantasies to life, hence promiscuity is there, just not realized.

Jong says that today, women are no longer shocked by Isadora's sexuality and the depiction of sex and fantasy, but readers were when the book was first released. Instead, she sees that book mirrors the lack of pleasure that many young women experience in sexual interactions. She cites the TV show Girls as an example of media depicting sexually-liberated women but without attention to female pleasure. Just like Isadora, the women on television and alive today struggle to reconcile the empowerment of sexual freedom with the disempowerment of sex without pleasure. However, she also sees growth in the female population that live alone and "whose lives are full with friends, travel, work, everything and who don’t feel that in some way they're inferior because they don’t have a man at their side" as being one extremely positive result of the way sexual liberation has transformed over the decades.[4]

The political battle over women's bodies today has also renewed the book's relevance in Jong's mind, constituting a 40th anniversary redistribution of the book. "All these states are introducing crazy anti-abortion rules... passing laws that they know are unconstitutional, shutting down Planned Parenthood clinics, and making it very hard...to get birth control." She cites those types of political moves as a regression from the progress set out by the Sexual Revolution. She also still feels that female authors are "second-class citizens in the publishing world," as Jennifer Weiner says in the introduction to the 40th anniversary edition: "it's very hard, if you write about women and women's struggles, to be seen as important with a capital 'I'."[4]

Character models

editJong denies that the novel is autobiographical but admits that it has autobiographical elements.[5] However, an article in The New Yorker recounts that Jong's sister, Suzanna Daou (née Mann), identified herself at a 2008 conference as the reluctant model for Isadora Wing's sister Randy and called the book "an exposé of my life when I was living in Lebanon." Daou angrily denounced the book, linked its characters to people in her own life, and took her sister to task for taking cruel liberties with them, especially Daou's husband. In the book, Isadora Wing's sister Randy is married to Pierre, who makes a pass at both Wing and her two other sisters. Jong dismissed her sister's claim by saying instead that "every intelligent family has an insane member."[6]

Film and radio adaptations

editMany attempts to adapt this property for Hollywood have been made, starting with Julia Phillips, who fantasized that it would be her debut as a director, from a screenplay by David Giler. The deal fell through and Erica Jong litigated, unsuccessfully.[7] In her second novel,[8] Jong created the character Britt Goldstein, a predatory and self-absorbed Hollywood producer devoid of both talent and scruples.

In May 2013 it was announced[9] that a screenplay version by Piers Ashworth had been green-lit by Blue-Sky Media, with Laurie Collyer directing.

References

edit- ^ "Fear of Flying (1973) by Erica Jong". Woman's Hour. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Bowman, David (June 14, 2003). "The 'Sex Woman'". Salon. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Open Road Media (2011-10-14), Erica Jong on Fear of Flying, archived from the original on 2021-12-21, retrieved 2017-11-16

- ^ a b c cunytv75 (2013-10-21), One to One: Erica Jong "Fear of Flying" 40th Anniversary, archived from the original on 2021-12-21, retrieved 2017-11-16

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fear of Flying – Erica Jong". Penguin Reading Guides. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Mead, Rebecca (April 14, 2008). "The Canon: Still Flying". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Phillips, Julia (1991). You'll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again. Random House. pp. 136 et seq. ISBN 0-394-57574-1.

- ^ Jong, Erica (2006). How to Save Your Own Life. Tarcher. ISBN 1585424994.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (10 May 2013). "Erica Jong's Fear of Flying Getting a Movie after 40 Years in Print". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

External links

edit- Quotations related to Fear of Flying at Wikiquote