Filip Višnjić (Serbian Cyrillic: Филип Вишњић, pronounced [fîliːp ʋîʃɲitɕ]; 1767–1834) was a Serbian epic poet and guslar. His repertoire included 13 original epic poems chronicling the First Serbian Uprising against the Ottoman Empire and four reinterpreted epics from different periods of history of Serbia.

Filip Višnjić | |

|---|---|

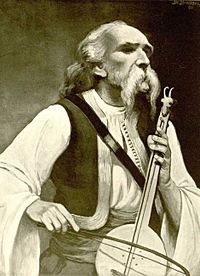

Drawing of Filip Višnjić by Josif Danilovac, 1901. | |

| Born | 1767 Gornja Trnova, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina) |

| Died | 1834 (aged 66–67) |

| Known for | Serbian epic poetry |

Born in a village near Ugljevik, Višnjić went blind at the age of eight or nine after contracting smallpox. He lost his family early in life, and began playing the gusle and reciting epic poetry around the age of 20. He spent years wandering the Balkans as a vagabond, and performed and begged for a living. His storytelling abilities attracted the attention of a number of influential figures, and around 1797, he married into an affluent family. In 1809, he relocated to Serbia with his wife and children, and experienced first-hand the First Serbian Uprising against the Ottomans. He performed in military camps, hoping to raise the morale of the rebels, and composed epic poems recounting the history of the uprising. The revolt was crushed by the Ottomans in 1813, and Višnjić and his family were forced to resettle in Austrian-controlled Syrmia, north of the Sava River.

In 1815, Višnjić performed for the linguist and folklorist Vuk Karadžić, who preserved his work in writing. Višnjić's epic poems were soon published as part of a collection of Serbian epic poetry that Karadžić had compiled. They were well received both in the Balkans and abroad. By this point, Višnjić was solely reinterpreting his old poems and no longer composing new ones. He lived in Syrmia until his death in 1834. Grk, the village in which he and his family lived, was later renamed Višnjićevo in his honour. Višnjić is widely considered one of Serbia's greatest gusle players and is revered for his contributions to the Serbian oral tradition. Notable Serbian scholar and Hellenist Miloš N. Đurić dubbed him the Serbian Homer.[1]

Life

editFilip Višnjić was born in the village of Vilića Guvno, near Gornja Trnova, Ugljevik, in 1767. At the time of his birth, Bosnia and Herzegovina was part of the Ottoman Empire.[2] His parents were Đorđe and Marija Vilić. He derived his surname from his mother's nickname, Višnja (meaning cherry). Višnjić's father died when he was young, and at the age of eight or nine, he lost his ability to see after a bout of smallpox. Following his father's death, Višnjić's mother remarried and moved to the village of Međaši in the lowlands of Semberija, taking her young son with her. When Višnjić was 20, the Ottomans massacred his family and burned their village.[3] Around this time, he began to play the gusle,[3] a one-stringed instrument used to accompany the recitation of epic poetry.[4][5]

For many years, Višnjić travelled as a vagrant throughout the Balkans, reaching as far as Shkodër. At first, he begged in order to earn a subsistence living, but soon his storytelling abilities attracted the attention of a number of influential figures, including Ivo Knežević, a nobleman from Semberija. Around 1798, Višnjić married Nasta Ćuković, who hailed from an affluent family. The marriage produced six children, several of whom died in infancy. In 1809, Višnjić left eastern Bosnia, crossed the Drina and ventured into Serbia, which beginning in 1804, had been the site of a violent anti-Ottoman rebellion under the leadership of Karađorđe. Višnjić and his family first settled in Loznica, then in Badovinci, and finally in Salaš Noćajski, where they were accommodated by the rebel leader Stojan Čupić. Thereafter, Višnjić travelled along the Drina, playing the gusle and reciting his epic poetry with the aim of raising the rebels' morale.[3] His recitations impressed many of the rebel commanders, including Karađorđe himself.[6]

By 1813, the rebels were teetering on the edge of defeat, and eventually the nine-year uprising was crushed. Most of the rebels fled across the Sava into the Austrian Empire and Višnjić followed them there. After several years in a refugee camp, in 1815, he settled in the village of Grk, near Šid, in the region of Syrmia.[6] Višnjić was living in Grk with his family when he became acquainted with the linguist and folklorist Vuk Karadžić, who wished to write down and preserve Višnjić's poetry.[7] Karadžić convinced Višnjić to visit him at the Šišatovac Monastery, at Fruška Gora, where the latter played the gusle and recited his poetry while the former took note. Shortly thereafter, Karadžić left Fruška Gora and made his way to Vienna, where he had Višnjić's epic poems published.[6] These appeared in the volume Narodna srbska pjesnarica (Songs of the Serbian People).[8]

Višnjić continued travelling across the region and reciting his poems despite his advancing age.[6] Everywhere he performed he was warmly received and accorded expensive gifts.[7] In 1816, he performed for the religious leader of the Habsburg Serbs, the Metropolitan of Karlovci, Stefan Stratimirović. By this time, Višnjić was exclusively reinterpreting his old poems, and was no longer composing new ones. Karadžić and several other prominent Serbian academics tried to convince Višnjić to return to Ottoman Serbia, hoping that this would inspire him to write new material, but the aging bard refused. Biographer Branko Šašić attributes Višnjić's refusal to his philosophical and ideological opposition to Miloš Obrenović, who had initiated a second uprising against the Ottomans in 1815. Višnjić is said not to have been able to forgive Obrenović for ordering Karađorđe's death.[6] Višnjić and his family prospered in Syrmia. He sent his son to school, acquired his own horse and cart, and according to Karadžić, "became a proper gentleman".[7][9] He died in Grk in 1834.[10]

Works

editVišnjić was not as prolific a bard as some of his contemporaries. His body of work contained four reinterpreted epics and 13 originals. All of his surviving poems were written during the First Serbian Uprising.[6] They are all set during the revolt and revolve around existent, as opposed to fictional, characters.[10] Their central theme is the struggle against the Ottoman Empire.[11] Ten out of Višnjić's 13 originals take place in the Podrinje, the region that straddles the Drina River.[10] In total, his opus consists of 5,001 lines of verse.[6] The following is a list of the epic poems whose authorship is attributed solely to Višnjić, as compiled by Šašić:[10]

- Početak bune protiv dahija (The Start of the Revolt against the Dahijas)

- Boj na Čokešini (The Battle of Čokešina)

- Boj na Salašu (The Battle of Salaš)

- Boj na Mišaru (The Battle of Mišar)

- Boj na Loznici (The Battle of Loznica)

- Uzimanje Užica (The Taking of Užice)

- Knez Ivo Knežević

- Luka Lazarević i Pejzo (Luka Lazarević and Pejzo)

- Miloš Stojićević i Meho Orugdžić (Miloš Stojićević and Meho Orugdžić)

- Hvala Čupićeva (In Praise of Čupić)

- Stanić Stanojlo

- Bjelić Ignjatije

- Lazar Mutap i Arapin (Lazar Mutap and the Arab)

Početak bune protiv dahija is widely considered Višnjić's magnum opus.[12] It focuses on the early stages of the First Serbian Uprising and the events leading up to it. Unlike the epic poems from the Kosovo Cycle, which deal with the Battle of Kosovo and its aftermath, Početak bune protiv dahija is a celebration of victory, not a commemoration of defeat.[13]

Višnjić was unique in that he was one of the few epic poets from the 18th and early 19th centuries whose works were not disseminated anonymously.[14] This is true of several other epic poets whose works Karadžić published, such as the recitalist Tešan Podrugović, and the blind female guslari Jeca, Stepanija and Živena.[8] Due to the predominantly oral character of Serbian epic poetry, the names of the original authors of many epic poems have been lost over time.[14]

The varying and meandrous style of the guslari, whereby the text of a published poem would not match word for word with that sung during a live performance, is due to the nature of epic poetry recitation itself. According to Slavic studies professor David A. Norris, the guslar "did not know his songs by heart, but as compositions made up of traditional phrases and formulaic expressions on which he could call each time he sang. His repertoire was based on a type of rapid composition recalling these fragments and lines and guiding them into place for each performance."[15] This gave gusle players such as Višnjić the ability to alter the content of their epic poems depending on the audience or occasion. The liberal use of artistic license also permeated the epic tradition.[5]

Legacy

editVišnjić is widely considered one of the greatest epic poets ever to have played the gusle.[16] With the publication of Karadžić's collections of Serbian epic poetry, Višnjić's works found a European audience, and were very well received.[17] As Serbia entered the modern age, epic poetry's standing as an influential art form diminished, prompting 20th-century literary scholar Svetozar Koljević to describe Višnjić's work as "the swansong of the epic tradition".[18]

Each November, Gornja Trnova hosts a cultural manifestation called Višnjićevi dani ("Višnjić's Days"), which attracts writers, theoreticians and poets, and features a Serbian Orthodox commemoration service.[19] In 1994, a commemorative plaque was installed in Gornja Trnova, marking the location where Višnjić was born. Bijeljina's municipal library is adorned with a plaque commemorating Višnjić and his work. The bard's likeness is incorporated into the municipal coats of arms of Bijeljina and Ugljevik. The village of Grk, in which Višnjić spent his final years, was renamed Višnjićevo in his honour. Numerous streets and schools in Serbia and Republika Srpska are named after him. During World War II, Višnjić's likeness was featured on 50 dinar banknotes issued by the Government of National Salvation. In modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, his likeness appears on 20 KM banknotes distributed in the Republika Srpska.[20] Višnjić is included in the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts' 1993 compendium The 100 most prominent Serbs.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Први су учитељи судбоносни". Politika Online. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ Šašić 1998, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Šašić 1998, p. 60.

- ^ Wachtel 1998, p. 32.

- ^ a b Carmichael 2015, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Šašić 1998, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Wilson 1970, p. 111.

- ^ a b Neubauer 2007, p. 272.

- ^ Burke 2009, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d Šašić 1998, p. 62.

- ^ Carmichael 2015, p. 28.

- ^ Zlatar 2007, p. 602.

- ^ Norris 2008, pp. 33–35.

- ^ a b Vucinich 1963, p. 108.

- ^ Norris 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Vidan 2016, p. 493.

- ^ Norris 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Judah 2000, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Ovčina, Đurđević-Alidžanović & Delić 2006, p. 180.

- ^ Čolović 2002, p. 73.

Bibliography

edit- Burke, Peter (2009). Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6507-6.

- Carmichael, Cathie (2015). A Concise History of Bosnia. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01615-6.

- Čolović, Ivan (2002). "Who Owns the Gusle? A Contribution to Research on the Political History of a Balkan Musical Instrument". In Resic, Sanimir; Törnquist-Plewa, Barbara (eds.). The Balkans in Focus: Cultural Boundaries in Europe. Riga, Latvia: Nordic Academic Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-91-89116-38-2.

- Judah, Tim (2000) [1997]. The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (2nd ed.). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08507-5.

- Neubauer, John (2007). "Introduction: Folklore and National Awakening". In Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (eds.). The Making and Remaking of Literary Institutions. History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Vol. 3. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 269–284. ISBN 978-90-272-9235-3.

- Norris, David A. (2008). Belgrade: A Cultural History. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-970452-1.

- Ovčina, Ismet; Đurđević-Alidžanović, Zijada; Delić, Ida (2006). Vodič kroz javne biblioteke Bosne i Hercegovine (in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina: Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine. ISBN 978-9958-500-26-8.

- Petrović, Ivana (2016). "On Finding Homer: The Impact of Homeric Scholarship on the Perception of South Slavic Oral Traditional Poetry". In Efstathiou, Athanasios; Karamanou, Ioanna (eds.). Homeric Receptions Across Generic and Cultural Contexts. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 315–330. ISBN 978-3-11-047783-2.

- Šašić, Branko (1998). "Филип Вишњић". Знаменити Шапчани и Подринци [Notable Residents of Šabac and the Podrinje] (in Serbian). Šabac, Serbia: Štampa "Dragan Srnić". pp. 59–62.

- Vidan, Aida (2016). "Serbian Poetry". In Greene, Roland; Cushman, Stephen (eds.). The Princeton Handbook of World Poetries. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 492–494. ISBN 978-1-4008-8063-8.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1963). "Some Aspects of the Ottoman Legacy". In Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (eds.). The Balkans in Transition: Essays on the Development of Balkan Life and Politics Since the Eighteenth Century. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. pp. 56–80. OCLC 395381.

- Wachtel, Andrew Baruch (1998). Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation: Literature and Cultural Politics in Yugoslavia. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3181-2.

- Wilson, Duncan (1970). The Life and Times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, 1787–1864: Literacy, Literature and National Independence in Serbia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821480-9.

- Zlatar, Zdenko (2007). Njegoš. The Poetics of Slavdom: The Mythopoeic Foundations of Yugoslavia. Vol. 2. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-8135-7.

Further reading

edit- Vojislav M. Jovanović (1954). "O liku Filipa Višnjića i drugih guslara Vukova vremena". Zbornik Matice srpske za književnost i jezik. Novi Sad: Projekat Rastko: 67–96.

External links

edit- Media related to Filip Višnjić at Wikimedia Commons