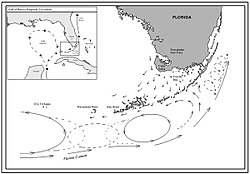

The Florida Current is a thermal ocean current that flows from the Straits of Florida around the Florida Peninsula and along the southeastern coast of the United States before joining the Gulf Stream Current near Cape Hatteras. Its contributing currents are the Loop Current and the Antilles Current. The current was discovered by Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León in 1513.

The Florida Current results from the movement of water pushed from the Atlantic into the Caribbean Sea by the rotation of the Earth (which exerts a greater force at the equator). The water piles up along Central America and flows northward through the Yucatán Channel into the Gulf of Mexico. The water is heated in the Gulf and forced out through the Florida Straits, between the Florida Keys in Hawk Channel and Cuba and flows northward along the east coast of the United States. The Florida Current is often referred to imprecisely as the Gulf Stream. In fact, the Florida Current joins the Gulf Stream off the east coast of Florida.

Transport

editThe Florida Current has an estimated mean transport of 30 Sv,[1][2][3] varying seasonally and interannually by as much as 10 Sv.[3] The volume transport increases as it flows farther north, reaching its maximum transport of 85 Sv near Cape Hatteras.[4] The water reaches a velocity of 1.8 metres per second (3.5 kn).

Seasonal variation

editThe seasonal variation of the Florida Current is relatively understudied. Seasonal variability in transports and eddies has been more intensely studied in the nearby Gulf Stream.[5][6][7] Past research indicates The Florida current reaches a maximum transport in July and a minimum transport in October, with a subsequent secondary maximum and minimum occurring in January and April, respectively.[8] Shorter variations in the transport may last between 2 and 20 days depending on wind current patterns, and are shortest during the summer months.[9] Therefore, the effects of the seasonal variability of the Florida Current on the wider reaching Gulf Stream is unknown. Wind speed, wind direction, topography, and temperature are important factors in determining current strength. Seasonal variation of weather in the South Florida region can help predict seasonal variability of current strength and transport. Stronger winds and higher temperatures lead to increased current flow due to the increase of the energy added into the system. Inversely, less wind speed and colder temperatures slow down currents and transport is typically lower. However, the Florida Current is formed in the Gulf of Mexico by the Yucatán Current and Gulf of Mexico Loop Current[10] and is important to monitor to determine flux in seasonal variations at the formation of the current.

Spatial scale

editLike transport, the spatial magnitude of the current increases along its course. At 27°N, it has a width of 80 km (50 mi); it gradually increases from 120 km (75 mi) at 29°N to 145 km (90 mi) where it flows into the Gulf Stream at 73°W.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Schmitz, William J. (1968-12-01). "On the transport of the Florida current". Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts. 15 (6): 679–693. Bibcode:1968DSRA...15..679S. doi:10.1016/0011-7471(68)90081-8.

- ^ Leaman, Kevin D.; Molinari, Robert L.; Vertes, Peter S. (1987-05-01). "Structure and Variability of the Florida Current at 27°N: April 1982–July 1984". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 17 (5): 565–583. Bibcode:1987JPO....17..565L. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1987)017<0565:SAVOTF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3670.

- ^ a b Schott, Friedrich A.; Lee, Thomas N.; Zantopp, Rainer (1988-09-01). "Variability of Structure and Transport of the Florida Current in the Period Range of Days to Seasonal". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 18 (9): 1209–1230. Bibcode:1988JPO....18.1209S. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1988)018<1209:VOSATO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3670.

- ^ Worthington; Kawai (1972). "Comparisons between deep sections across the Kuroshio and the Florida Current and Gulf Stream". In Stommel; Yoshida (eds.). Kuroshio, its Physical Aspects. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. pp. 371–385.

- ^ Fu, L. (1987). "Seasonal variability of the Gulf Stream from satellite altimetry". Journal of Geophysical Research. 92 (C1): 749. Bibcode:1987JGR....92..749F. doi:10.1029/JC092iC01p00749.

- ^ Zhai, X. (2008). "On the seasonal variability of eddy kinetic energy in the Gulf Stream region". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (24). Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3524609Z. doi:10.1029/2008GL036412.

- ^ Rossby, T. (2010). "On the variability of Gulf Stream transport from seasonal to decadal timescales". Journal of Marine Research. 68 (3–4): 503. doi:10.1357/002224010794657128.

- ^ Montgomery, R (1938). "Fluctuations in the monthly sea level on the eastern U.S. Coast as related to dynamics of the western North Atlantic Ocean". Journal of Marine Research. 1: 32–37. doi:10.1357/002224038806440584.

- ^ Lee, T; Williams, E (1988). "Wind-forced transport fluctuations of the Florida Current". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 18 (7): 937–946. Bibcode:1988JPO....18..937L. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1988)018<0937:wftfot>2.0.co;2.

- ^ "The Florida Current is a strong oceanic current flowing northward along the eastern coast of Florida carrying warm tropical waters that eventually feed the Gulf Stream". floridakeys.noaa.gov. NOAA. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Leaman, K; Johns, E; Rossby, T (1989). "The average distribution of volume transport and Potential Vorticity with temperature at three sections across the Gulf Stream". Journal of Physical Oceanography. 19 (1): 36–51. Bibcode:1989JPO....19...36L. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1989)019<0036:TADOVT>2.0.CO;2.

External links

edit- Florida Current Transport Time Series and Cruises; Western Boundary Time Series

- Joanna Gyory et al. The Florida Current; University of Miami