Fort Taber District or the Fort at Clark's Point is a historic American Civil War-era military fort on Wharf Road within the former Fort Rodman Military Reservation in New Bedford, Massachusetts. The fort is now part of Fort Taber Park, a 47-acre town park located at Clark's Point. Fort Taber was an earthwork built nearby with city resources and garrisoned 1861-1863 until Fort Rodman was ready for service.

Fort Taber District | |

Fort Rodman | |

| Location | New Bedford, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°35′35″N 70°54′05″W / 41.59306°N 70.90139°W |

| Built | 1861 |

| Architect | Robert E. Lee, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| Architectural style | Third System fortification |

| NRHP reference No. | 73001954 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | February 8, 1973 |

Fort Taber

editAfter the Civil War began in April 1861, it was apparent that the Fort at Clark's Point was still years from completion. Fort Taber, a small earthwork with six cannons, was built nearby with city resources, and named after New Bedford's mayor during that period.[2] It provided a temporary defense until the stone fort was garrisoned in 1863. Fort Taber is marked by a stone outline today, directly behind the stone fort. It was noted at the time that the stone fort's presence interfered with effective fire from Fort Taber, and a battery of field artillery was emplaced east of Fort Taber.[3][4] The Fort Taber name was unofficially used to refer to the Fort at Clark's Point for many years, even by the garrison in letters home, and is used to refer to the stone fort in some recent references.[5]

Fort Rodman

editCivil War era

editAlso known as the Old Stone Fort, Fort Rodman (known as "Fort at Clark's Point" until 1898) began construction in 1857 under the third system of US fortifications, and in 1862 construction became overseen by Henry Robert, author of Robert's Rules of Order and an Army Corps of Engineers officer.[2] The fort, as built, had emplacements for 72 cannon in three tiers; a fourth tier was originally planned, but this was removed from the design to allow more timely completion.[5] Construction was halted in 1871, and the fort as planned was never completed.

The Fort Rodman/Fort Taber Military Museum is open Wednesdays through Sundays between 1:00pm and 4:00pm. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays.

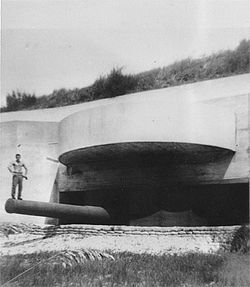

Endicott period

editWith new batteries being constructed under the Endicott program in 1898, the U.S. Army officially named the military reservation at the site and the fort as Fort Rodman Military Reservation, in honor of Lieutenant Colonel Logan Rodman, a New Bedford native with the 38th Massachusetts Infantry who died in the assault on Port Hudson, Louisiana in 1863. It was the primary fort of the Coast Defenses of New Bedford, and was garrisoned by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps.[6] Along with gun batteries, facilities for planting and controlling an underwater minefield were built. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[4]

The Endicott period batteries at Fort Rodman were built 1898-1902, with other batteries added later as follows:[3][6]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walcott | 1 | 8-inch gun M1888 | disappearing M1896 | 1899-1942 |

| Barton | 1 | 8-inch gun M1888 | disappearing M1896 | 1899-1942 |

| Cross | 2 | 5-inch gun M1900 | pedestal M1903 | 1902-1920 |

| Craig | 2 | 3-inch gun M1898 | masking parapet M1898 | 1902-1920 |

| Gaston | 2 | 3-inch gun M1898 | masking parapet M1898 | 1902-1920 |

| Milliken | 2 | 12-inch gun M1895 | M1917 long-range barbette | 1921-1946 |

| Unnamed | 2 | 155 mm gun M1918 | Towed on Panama mounts | 1938-1945 |

Battery Walcott was named for William H. Walcott of the 17th U.S. Infantry in the Civil War. Battery Barton was named for William Barton of the Revolutionary War. Battery Cross was named for Charles E. Cross, an engineer officer killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg in the Civil War. Battery Craig was named for Presley O. Craig, 2nd U.S. Artillery, killed at the First Battle of Bull Run in the Civil War. Battery Gaston was named for William Gaston, 1st U.S. Dragoons, killed in 1858 fighting Native Americans. Battery Milliken was named for Alfred S. Milliken, an engineer officer killed in World War I.[3]

World War I through World War II

editAfter the American entry into World War I many 5-inch guns were withdrawn from forts for potential service on field carriages on the Western Front. However, Battery Cross's two guns were removed in 1917 and installed on the Army transport ship USAT Kilpatrick. They were returned to Fort Rodman in March 1919, and scrapped in 1921 under a general removal from Coast Artillery service of 5-inch guns. The 8-inch guns of Batteries Walcott and Barton were dismounted for potential service as railway artillery in June 1918, but were remounted later without leaving the fort.[3]

In 1920 the Driggs-Seabury M1898 3-inch guns of Batteries Craig and Gaston were removed due to a general removal from service of this type of gun; they were not replaced.[3]

Battery Milliken was built 1917-1921 as part of a general upgrade of the Coast Artillery with existing 12-inch M1895 guns on new long-range carriages, initially in open mounts.[3] Compared with disappearing carriages, this increased the range of this type of gun from 18,400 yards (16,800 m) to 30,100 yards (27,500 m).[7] This effectively replaced the fort's previous 8-inch guns, but those were not removed until World War II.[3] Battery Milliken housed the post switchboard, and during World War II this was operated by the Women's Army Corps, for which the latrines were re-arranged.

In 1925 the Coast Defenses of New Bedford were renamed the Harbor Defenses of New Bedford, as were all similar commands.[8]

In 1938 a battery of two 155 mm guns on "Panama mounts" (circular concrete platforms) was built at Fort Rodman. In 1940-1941 numerous temporary buildings were constructed on site to accommodate newly mobilized units. In 1942 the two 8-inch guns of Batteries Walcott and Barton were scrapped, leaving only the 12-inch Battery Milliken and the 155 mm battery active. Battery Milliken was casemated for protection against air attack during the war.[3] HD New Bedford was garrisoned by the 23rd Coast Artillery from February 1940 through October 1944. This unit was a battalion for most of the war, but was redesignated as a regiment September 1943 through February 1944.[9][10]

In 1946, with the war over, Fort Rodman was disarmed and subsequently turned over to the Commonwealth.

Associated batteries

editSeveral additional small-caliber batteries defended New Bedford and Buzzards Bay during World War II. Chief among these was Battery 210 at Mishaum Point Military Reservation in Dartmouth. It had two 6-inch M1 guns in long-range shielded mounts with a large bunker for ammunition and fire control between them. It currently has a private residence built on it. A two-gun 155 mm battery was at the location until the 6-inch battery was completed in 1945, along with the harbor entrance control post for New Bedford.[3][4][6]

Defending the passage to New Bedford between Dartmouth and Cuttyhunk Island were two batteries of 90 mm guns, one at Barneys Joy Point Military Reservation and one on Cuttyhunk Island, part of the Elizabeth Islands Military Reservation. These were called Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat Batteries (AMTB) 931 and 932, respectively. The AMTB batteries had an authorized strength of four 90 mm guns, two on fixed mounts and two on towed mounts. An additional 90 mm battery, AMTB 933, was on Nashawena Island, just east of Cuttyhunk Island.[3][4][6]

Protecting the southern entrance to the Cape Cod Canal was a two-gun 155 mm battery on Panama mounts, replaced in 1943 by AMTB 934, at Butler Point Military Reservation in Marion.[3][4]

Present

editThe fort's guns were all scrapped by 1948. The fort grounds and garrison buildings became a military reserve center, and eventually a wastewater treatment plant was built on part of the site. University of Massachusetts Dartmouth (Southeastern Massachusetts University prior to 1991) occupies some of the fort's buildings. The reserve center closed in the 1970s. Today most of the former fort is a public park, but as of 2016 the stone fort and gun batteries are fenced off, and the Endicott batteries are overgrown. The stone fort has occasionally been opened for special events.

Lighthouse

editThe Clarks Point Light stands on the parapet of the fort. Originally established as a freestanding tower, it was moved to the fort in 1869 because the fort's walls obscured the beacon from some angles. it was deactivated in 1898, but was relit in 2001 by the city as a private aid to navigation.

Fort Taber Historical Association Museum

editThe Fort Taber Historical Association Museum is located at Fort Taber Park, and features a miniature model of the fort, uniforms from different eras during the fort's active use, photos and military memorabilia. It is operated by the Fort Taber/Fort Rodman Historical Association and opened in 2004.

Park amenities

editThe park includes several gun batteries, and American Revolution, American Civil War, and World War II re-enactments are held in the park. The stone fort and 20th-century batteries are fenced off but can be viewed.

A World War II M-4 Sherman tank recovered from the debris of Exercise Tiger is on display in the park, and serves as the US memorial for the dead of the Exercise. A commemoration ceremony is held annually.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Fort Taber Park at New Bedford city website Archived 2013-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fort Rodman article at FortWiki.com

- ^ a b c d e Fort Taber at NorthAmericanForts.com

- ^ a b Weaver, pp. 115–120

- ^ a b c d Berhow, p. 206

- ^ Berhow, p. 61

- ^ Coast Artillery Organization: A Brief Overview at the Coast Defense Study Group website

- ^ Gaines, William C., Coast Artillery Organizational History, 1917-1950, Coast Defense Journal, vol. 23, issue 2, p. 15

- ^ Stanton, pp. 459, 484

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1991). World War II Order of Battle. Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-775-9.

- Weaver II, John R. (2018). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867, 2nd Ed. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. ISBN 978-1-7323916-1-1.

External links

edit- Fort Taber Park - City of New Bedford

- Fort Taber/Fort Rodman Park at Destination New Bedford

- Fort Taber/Fort Rodman Historical Association

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts

- NorthAmericanForts.com, lists most US forts