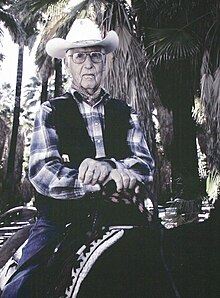

Frank Mitchell Bogert (January 1, 1910 – March 22, 2009) was an American cowboy, professional rodeo announcer, author, and politician best known as the longtime mayor of Palm Springs, California.

Frank Bogert | |

|---|---|

| |

| 8th & 15th Mayor of Palm Springs | |

| In office April 1958 – January 1966 | |

| Preceded by | Gerald K. Sanborn |

| Succeeded by | George Beebe, Jr. |

| In office April 1982 – April 1988 | |

| Preceded by | John Doyle |

| Succeeded by | Sonny Bono |

| Member of the City Council | |

| In office 1958–1966 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 1, 1910 Mesa, Colorado, U.S. |

| Died | March 22, 2009 (aged 99) Palm Springs, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

Born in Mesa, Colorado to Henry Kneeland Bogert and Adaline Esther Mitchell, he was raised in the California mountain town of Wrightwood in San Bernardino County. He was a rodeo colleague and distant relative to cowboy artist Earl W. Bascom.

Bogert arrived in Palm Springs in 1927, becoming the city's first chamber of commerce manager in 1939. In the later 1930s he was the manager of the Palm Springs Racquet Club.[1]

In 1958, Bogert was elected to the Palm Springs City Council, becoming mayor soon after, serving for eight years. He was elected to the position for two more two-year terms in 1982.

Bogert worked closely with Gene Autry to bring the California Angels to Palm Springs for spring training. In 1987 he wrote a book, Palm Springs: First Hundred Years,[2] a favorite of famous area resident Bob Hope.

In 1997, a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs, California, Walk of Stars was dedicated to him.[3]

Early life

editThe youngest of eight siblings, Franklin Mitchell Bogert was born on January 1, 1910 to Henry Kneeland Bogert (1868-1959) and Adaline Esther Bogert (1870-1970) in Grand Mesa, Colorado.[4] The Bogert family initially lived a refined life on a 250-square-mile ranch. As a young child, Bogert learned to ride a horse and assisted with the raising of cattle and other ranch chores. However, this came to an end as the family lost their wealth and ranch as the result of fallout from the Panic of 1907.[5]

Shortly thereafter, the Bogert family relocated to Los Angeles where Frank attended the 24th Street Grammar School followed by the Los Angeles High School. In high school, he was a successful football player and worked odd jobs. It was also around this time that he began to take riding a roping lessons near the family’s home on Rimpau Boulevard, where the development of Los Angeles opened into rural open space. In 1926, when he was 16, he took a job as a stable hand at a stable in Wrightwood, and when the owner died the following year, he left his sixty horses to Bogert and another man named Rod Abbott.[5]

Shortly thereafter, after considering a place to put the horses out for pasture, Bogert and Abbott moved all sixty horses about ninety miles over the course of three days to Palm Springs.[6] At the time, Palm Springs was in the early stages of becoming a recreation destination, with hotels such as the El Mirador and Desert Inn attracting wealthy tourists during the town’s temperate winters.[7] Bogert and Abbott built a small horse riding operation that took these tourists into Palm Canyon for a nominal charge of $1.[6] During this time, Bogert still had not moved to Palm Springs, but would return on weekends while Abbott ran the business during the week. Bogert was also attending the University of California, Los Angeles, which he had entered in hopes of courting Marion Dale, a future Olympic athlete. Partially due to the busy nature of his and Abbott’s horse operation, he did not finish his degree.[5]

Section 14 Indigenous Land

editAs Mayor of Palm Springs in the mid-1960's, Bogert was an advocate for the eviction of non-Native Americans from Section 14, a tract of land held by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians but leased to others. The city directed that the tribe terminate short-term leases granted to them and used city funds to clear the land for redevelopment, including burning the homes.[8] The evicted residents of Section 14 were mostly Black and Latino who did not want to move.[9]

The Palm Springs Human Relations Commission cited this history, as well as a conflict of interest while Bogert acted as conservator for tribal land which was being demolished by the city, and alleged racist comments regarding the "poor Blacks" who lived in Section 14, as justification for removing a statue of Bogert on horseback[10] placed in 1990 in front of the Palm Springs City Hall.[11] The City Council of Palm Springs ordered its removal in 2021 and formally apologized for the eviction of the Section 14 residents.[12] After legal objections to its removal from Bogert's supporters and family members were rejected by the courts, the statue was relocated on July 13, 2022.[13]

Bibliography

edit- View From the Saddle: Characters Who Crossed My Trail. Palm Springs: ETC Publications. 2006. p. 232. ISBN 978-0882801582. LCCN 2005049514. OCLC 62110026. LCC F869.P18 B65 2006

- Palm Springs: First Hundred Years. Palm Springs: Palm Springs Library. 2003 [1987]. p. 288. ISBN 978-0961872427. OCLC 51059207.

- Prickly Pears : Interviews with Billie Lipps and Tommy Lipps Von Mastrigt (VHS). Palm Springs Library: Portraits of Historical Palm Springs, No. 54. 1989. OCLC 40933409.

- Anthony Burke. Palm Springs: Why I Love You. Palm Desert: Palmesa. 1978. OCLC 5346893.

- Lawrence Culver. Frontier of Leisure: Southern California and the Shaping of Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press. 2010. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9780195382631.

References

edit- ^ Rippingale, Sally Presley (1984). "The Thirties". The History of the Racquet Club of Palm Springs. Yucaipa, CA: US Business Specialties. p. 146. LCCN 85226534. OCLC 13526611.

- ^ Palm Springs: First Hundred Years. Palm Springs: Palm Springs Library. 2003 [1987]. p. 288. ISBN 978-0961872427. OCLC 51059207.

- ^ Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau. 1910 United States Federal Census, Mesa, Mesa, Colorado; Roll: T624_122; Page: 3b; Enumeration District: 0088; FHL microfilm: 1374135. Ancestry.com.

- ^ a b c Conrad, Tracy (January 7, 2024). "Palm Springs history: Frank Bogert's journey from a Colorado ranch to Southern California". Desert Sun.

- ^ a b Conrad, Tracy (January 21, 2024). "History: Frank Bogert was a known horseman, but photography also played a role in his life". Desert Sun. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ Culver, Lawrence (2012). The frontier of leisure: Southern California and the shaping of modern America. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 156–159. ISBN 978-0-19-989192-4.

- ^ Holland, Gale (2022-11-30). "Black and Latino residents burned out of Palm Springs seek city reparations". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ "'City-engineered holocaust': Musician [Alvin Taylor] reflects on boyhood home". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Thropay, Caitlin (2020-06-24). "Petition to remove Frank Bogert's statue; Palm Springs Historical Society and Jack Jones, friend of Bogert respond". KESQ. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Biography and news of Bogert's death at Mydesert.com(subscription required)

- ^ Ingrassia, Jake (2021-09-30). "Palm Springs to apologize for Section 14 destruction; moves forward with process to remove Frank Bogert statue". KESQ. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Talkington, Mark (2022-10-11). "Legal case around removal of Frank Bogert statue from in front of City Hall stopped in its tracks after judge's ruling". The Palm Springs Post. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

External links

edit- "Frank Bogert, the Man not the Myth". INformed People Magazine (Special Issue). Big Media USA Inc: 1, 4, 7–8, 11, 26–30. August 4, 2021.