This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (February 2023) |

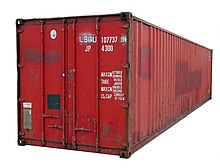

An intermodal container, often called a shipping container, or cargo container, (or simply “container”) is a large metal crate designed and built for intermodal freight transport, meaning these containers can be used across different modes of transport – such as from ships to trains to trucks – without unloading and reloading their cargo.[1] Intermodal containers are primarily used to store and transport materials and products efficiently and securely in the global containerized intermodal freight transport system, but smaller numbers are in regional use as well. It is like a boxcar that does not have wheels. Based on size alone, up to 95% of intermodal containers comply with ISO standards,[2] and can officially be called ISO containers. These containers are known by many names: freight container, sea container, ocean container, container van or sea van, sea can or C can, or MILVAN,[3][4] or SEAVAN.[citation needed] The term CONEX (Box) is a technically incorrect carry-over usage of the name of an important predecessor of the ISO containers: the much smaller steel CONEX boxes used by the U.S. Army.

Intermodal containers exist in many types and standardized sizes, but 90 percent of the global container fleet are "dry freight" or "general purpose" containers:[2][5] durable closed rectangular boxes, made of rust-retardant Corten steel; almost all 8 feet (2.44 m) wide, and of either 20 or 40 feet (6.10 or 12.19 m) standard length, as defined by International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard 668:2020.[2][6] The worldwide standard heights are 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m) and 9 feet 6 inches (2.90 m) – the latter are known as High Cube or Hi-Cube (HC or HQ) containers.[7] Depending on the source, these containers may be termed TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units), reflecting the 20- or 40-foot dimensions.

Invented in the early 20th century, 40-foot intermodal containers proliferated during the 1960s and 1970s under the containerization innovations of the American shipping company SeaLand. Like cardboard boxes and pallets, these containers are a means to bundle cargo and goods into larger, unitized loads that can be easily handled, moved, and stacked, and that will pack tightly in a ship or yard. Intermodal containers share a number of construction features to withstand the stresses of intermodal shipping, to facilitate their handling, and to allow stacking. Each has a unique ISO 6346 reporting mark.

In 2012, there were about 20.5 million intermodal containers in the world of varying types to suit different cargoes.[6][nb 1] Containers have largely supplanted the traditional break bulk cargo; in 2010, containers accounted for 60% of the world's seaborne trade.[9][10] The predominant alternative methods of transport carry bulk cargo, whether gaseous, liquid, or solid—e.g., by bulk carrier or tank ship, tank car, or truck. For air freight, the lighter weight IATA-defined unit load devices are used.

History

edit-

Transferring freight containers on the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS; 1928)

-

Freight car in railway museum Bochum-Dahlhausen, showing four different UIC-590 pa-containers

-

Side of Vietnam era U.S. Army steel 'CONEX' box container (3D)

-

In 1975, many containers still featured riveted aluminum sheet-and-post wall construction, instead of welded, corrugated steel.[11]

Origins

editContainerization has its origins in early coal mining regions in England beginning in the late 18th century. In 1766 James Brindley designed the box boat 'Starvationer' with ten wooden containers, to transport coal from Worsley Delph (quarry) to Manchester by Bridgewater Canal. In 1795, Benjamin Outram opened the Little Eaton Gangway, upon which coal was carried in wagons built at his Butterley Ironwork. The horse-drawn wheeled wagons on the gangway took the form of containers, which, loaded with coal, could be transshipped from canal barges on the Derby Canal, which Outram had also promoted.[12]

By the 1830s, railways were carrying containers that could be transferred to other modes of transport. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway in the UK was one of these, making use of "simple rectangular timber boxes" to convey coal from Lancashire collieries to Liverpool, where a crane transferred them to horse-drawn carriages.[13] Originally used for moving coal on and off barges, "loose boxes" were used to containerize coal from the late 1780s, at places like the Bridgewater Canal. By the 1840s, iron boxes were in use as well as wooden ones. The early 1900s saw the adoption of closed container boxes designed for movement between road and rail.

Creation of international standards

editThe first international standard for containers was established by the Bureau International des Containers et du Transport Intermodal (B.I.C.) in 1933, and a second one in 1935, primarily for transport between European countries. American containers at this time were not standardized, and these early containers were not yet stackable – neither in the U.S. nor Europe. In November 1932, the first container terminal in the world was opened by the Pennsylvania Rail Road Company in Enola, Pennsylvania. Containerization was developed in Europe and the US as a way to revitalize rail companies after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, in New York, which resulted in economic collapse and a drop in all modes of transport.[14]

Mid 20th century innovations

editIn April 1951 at Zürich Tiefenbrunnen railway station, the Swiss Museum of Transport and the Bureau International des Containers (BIC) held demonstrations of container systems for representatives from a number of European countries, and from the United States. A system was selected for Western Europe, based on the Netherlands' system for consumer goods and waste transportation called Laadkisten (lit. "Loading chests"), in use since 1934. This system used roller containers for transport by rail, truck and ship, in various configurations up to 5,500 kg (12,100 lb) capacity, and up to 3.1 by 2.3 by 2 metres (10 ft 2 in × 7 ft 6+1⁄2 in × 6 ft 6+3⁄4 in) in size.[15][16] This became the first post World War II European railway standard of the International Union of Railways – UIC-590, known as "pa-Behälter". It was implemented in the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, West Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark.[17]

The use of standardized steel shipping containers began during the late 1940s and early 1950s, when commercial shipping operators and the US military started developing such units.[18] In 1948 the U.S. Army Transportation Corps developed the "Transporter", a rigid, corrugated steel container, able to carry 9,000 pounds (4,100 kg). It was 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) long, 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) wide, and 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m) high, with double doors on one end, was mounted on skids, and had lifting rings on the top four corners.[19] After proving successful in Korea, the Transporter was developed into the Container Express (CONEX) box system in late 1952. Based on the Transporter, the size and capacity of the Conex were about the same,[nb 2] but the system was made modular, by the addition of a smaller, half-size unit of 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) long, 4 ft 3 in (1.30 m) wide and 6 ft 10+1⁄2 in (2.10 m) high.[22][23][nb 3] CONEXes could be stacked three high, and protected their contents from the elements.[20] By 1965 the US military used some 100,000 Conex boxes, and more than 200,000 in 1967,[22][26] making this the first worldwide application of intermodal containers.[20] Their invention made a major contribution to the globalization of commerce in the second half of the 20th century, dramatically reducing the cost of transporting goods and hence of long-distance trade.[27][28]

From 1949 onward, engineer Keith Tantlinger repeatedly contributed to the development of containers, as well as their handling and transportation equipment. In 1949, while at Brown Trailers Inc. of Spokane, Washington, he modified the design of their stressed skin aluminum 30-foot trailer, to fulfil an order of two-hundred 30 by 8 by 8.5 feet (9.14 m × 2.44 m × 2.59 m) containers that could be stacked two high, for Alaska-based Ocean Van Lines. Steel castings on the top corners provided lifting and securing points.[29]

In 1955, trucking magnate Malcom McLean bought Pan-Atlantic Steamship Company, to form a container shipping enterprise, later known as Sea-Land. The first containers were supplied by Brown Trailers Inc, where McLean met Keith Tantlinger, and hired him as vice-president of engineering and research.[30] Under the supervision of Tantlinger, a new 35 ft (10.67 m) x 8 ft (2.44 m) x 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) Sea-Land container was developed, the length determined by the maximum length of trailers then allowed on Pennsylvanian highways. Each container had a frame with eight corner castings that could withstand stacking loads.[31] Tantlinger also designed automatic spreaders for handling the containers, as well as the twistlock mechanism that connects with the corner castings.

Modern form

editContainers in their modern 21st-century form first began to gain widespread use around 1956. Businesses began to devise a structured process to utilize and to get optimal benefits from the role and use of shipping containers. Over time, the invention of the modern telecommunications of the late 20th century made it highly beneficial to have standardized shipping containers and made these shipping processes more standardized, modular, easier to schedule, and easier to manage.[32]

Two years after McLean's first container ship, the Ideal X, started container shipping on the US East Coast,[33] Matson Navigation followed suit between California and Hawaii. Just like Pan-Atlantic's containers, Matson's were 8 ft (2.44 m) wide and 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) high, but due to California's different traffic code Matson chose to make theirs 24 ft (7.32 m) long.[34] In 1968, McLean began container service to South Vietnam for the US military with great success.

Modern ISO standards

editISO standards for containers were published between 1968 and 1970 by the International Maritime Organization. These standards allow for more consistent loading, transporting, and unloading of goods in ports throughout the world, thus saving time and resources.[35]

The International Convention for Safe Containers (CSC) is a 1972 regulation by the Inter-governmental Maritime Consultative Organization on the safe handling and transport of containers. It decrees that every container traveling internationally be fitted with a CSC Safety-approval Plate.[36][37] This holds essential information about the container, including age, registration number, dimensions and weights, as well as its strength and maximum stacking capability.

Impact of industry changes on workers

editLongshoremen and related unions around the world struggled with this revolution in shipping goods.[38][39] For example, by 1971 a clause in the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) contract stipulated that the work of "stuffing" (filling) or "stripping" (emptying) a container within 50 miles (80 km) of a port must be done by ILA workers, or if not done by ILA, that the shipper needed to pay royalties and penalties to the ILA. Unions for truckers and consolidators argued that the ILA rules were not valid work preservation clauses, because the work of stuffing and stripping containers away from the pier had not traditionally been done by ILA members.[38][39] In 1980 the Supreme Court of the United States heard this case and ruled against the ILA.[38][39]

Impact in worldwide supply shortage of 2020 to present

editSome experts have said that the centralized, continuous shipping process made possible by containers has created dangerous liabilities: one bottleneck, delay, or other breakdown at any point in the process can easily cause major delays everywhere up and down the supply chain.[32]

The reliance on containers exacerbated some of the economic and societal damage from the 2021 global supply chain crisis of 2020 and 2021, and the resulting shortages related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In January 2021, for example, a shortage of shipping containers at ports caused shipping to be backlogged.[40][41][42]

Marc Levinson, author of Outside the Box: How Globalization Changed from Moving Stuff to Spreading Ideas and The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, said in an interview:[32]

Because of delays in the process, it's taking a container longer to go from its origin to its final destination where it's unloaded, so the container is in use longer for each trip. You've just lost a big hunk of the total capacity because the containers can't be used as intensively. We've had in the United States an additional problem, which is that the ship lines typically charge much higher rates on services from Asia to North America than from North America to Asia. This has resulted in complaints, for example, from farmers and agricultural companies, that it's hard to get containers in some parts of the country because the ship lines want to ship them empty back to Asia, rather than letting them go to South Dakota and load over the course of several days. So we've had exporters in the United States complaining that they have a hard time finding a container that they can use to send their own goods abroad.[32]

Description

editNinety percent of the global container fleet consists of "dry freight" or "general purpose" containers – both of standard and special sizes.[2][5] And although lengths of containers vary from 8 to 56 feet (2.4 to 17.1 m), according to two 2012 container census reports[nb 4] about 80% of the world's containers are either 20- or 40-foot standard-length boxes of the dry freight design.[6] These typical containers are rectangular, closed box models, with doors fitted at one end, and made of corrugated weathering steel (commonly known as CorTen)[nb 5] with a plywood floor.[44] Although corrugating the sheet metal used for the sides and roof contributes significantly to the container's rigidity and stacking strength, just like in corrugated iron or in cardboard boxes, the corrugated sides cause aerodynamic drag, and up to 10% fuel economy loss in road or rail transport, compared to smooth-sided vans.[45]

Standard containers are 8 feet (2.44 m) wide by 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) high,[nb 6] although the taller "High Cube" or "hi-cube" units measuring 9 feet 6 inches (2.90 m) have become very common in recent years[when?]. By the end of 2013, high-cube 40 ft containers represented almost 50% of the world's maritime container fleet, according to Drewry's Container Census report.[47]

About 90% of the world's containers are either nominal 20-foot (6.1 m) or 40-foot (12.2 m) long,[6][48] although the United States and Canada also use longer units of 45 ft (13.7 m), 48 ft (14.6 m) and 53 ft (16.15 m). ISO containers have castings with openings for twistlock fasteners at each of the eight corners, to allow gripping the box from above, below, or the side, and they can be stacked up to ten units high.[49]

Although ISO standard 1496 of 1990 only required nine-high stacking, and only of containers rated at 24,000 kg (53,000 lb),[50] current Ultra Large Container Vessels of the Post New Panamax and Maersk Triple E class are stacking them ten or eleven high.[51][52] Moreover, vessels like the Marie Maersk no longer use separate stacks in their holds, and other stacks above deck – instead they maximize their capacity by stacking continuously from the bottom of the hull, to as much as 21 high.[53] This requires automated planning to keep heavy containers at the bottom of the stack and light ones on top to stabilize the ship and to prevent crushing the bottom containers.

Regional intermodal containers, such as European, Japanese and U.S. domestic units however, are mainly transported by road and rail, and can frequently only be stacked up to two or three laden units high.[49] Although the two ends are quite rigid, containers flex somewhat during transport.[54]

Container capacity is often expressed in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU, or sometimes teu). A twenty-foot equivalent unit is a measure of containerized cargo capacity equal to one standard 20-foot (6.1 m) long container. This is an approximate measure, wherein the height of the box is not considered. For example, the 9 ft 6 in (2.9 m) tall high-cube, as well as 4-foot-3-inch half-height (1.3 m) 20-foot (6.1 m) containers are equally counted as one TEU. Similarly, extra long 45 ft (13.72 m) containers are commonly counted as just two TEU, no different from standard 40 feet (12.19 m) long units. Two TEU are equivalent to one forty-foot equivalent unit (FEU).[55][56]

In 2014 the global container fleet grew to a volume of 36.6 million TEU, based on Drewry Shipping Consultants' Container Census.[57][nb 7] Moreover, in 2014 for the first time in history 40-foot High-Cube containers accounted for the majority of boxes in service, measured in TEU.[57] In 2019 it was noted by global logistics data analysis startup Upply[58] that China's role as 'factory of the world' is further incentivizing the use of 40-foot containers, and that the computational standard 1 TEU boxes only make up 20% of units on major east–west liner routes, and demand for shipping them keeps dropping.[59] In the 21st century, the market has shifted to using 40-foot high-cube dry and refrigerated containers more and more predominantly. Forty-foot units have become the standard to such an extent that the sea freight industry now charges less than 30% more for moving a 40-ft unit than for a 1 TEU box. Although 20-ft units mostly have heavy cargo, and are useful for stabilizing both ships and revenue,[nb 8] carriers financially penalize 1 TEU boxes by comparison.[59]

For container manufacturers, 40-foot High-Cubes now dominate market demand both for dry and refrigerated units.[59] Manufacturing prices for regular dry freight containers are typically in the range of $1750–$2000 U.S. per CEU (container equivalent unit),[57] and about 90% of the world's containers are made in China.[48] The average age of the global container fleet was a little over 5 years from end 1994 to end 2009, meaning containers remain in shipping use for well over 10 years.[8]

Gooseneck tunnel

editA gooseneck tunnel, an indentation in the floor structure, that meshes with the gooseneck on dedicated container semi-trailers, is a mandatory feature in the bottom structure of 1AAA and 1EEE (40- and 45-ft high-cube) containers, and optional but typical on standard height, forty-foot and longer containers.[62]

Types

editOther than the standard, general purpose container, many variations exist for use with different cargoes. The most prominent of these are refrigerated containers (also called reefers) for perishable goods, that make up 6% of the world's shipping boxes.[5][48] Tanks in a frame, for bulk liquids, account for another 0.75% of the global container fleet.[5]

Although these variations are not of the standard type, they mostly are ISO standard containers – in fact the ISO 6346 standard classifies a broad spectrum of container types in great detail. Aside from different size options, the most important container types are:[63][nb 10]

- General-purpose dry vans, for boxes, cartons, cases, sacks, bales, pallets, drums, etc., Special interior layouts are known, such as:

- Ventilated containers. Essentially dry vans, but either passively or actively ventilated. For instance for organic products requiring ventilation.

- Temperature controlled – either insulated, refrigerated, and/or heated containers, for perishable goods

- Tank containers, for liquids, gases, or powders. Frequently these are dangerous goods, and in the case of gases one shipping unit may contain multiple gas bottles

- Bulk containers (sometimes bulktainers), either closed models with roof-lids, or hard or soft open-top units for top loading, for instance for bulk minerals. Containerized coal carriers and "bin-liners" (containers designed for the efficient road and rail transportation of rubbish from cities to recycling and dump sites) are used in Europe.

- Open-top and open-side containers, for instance for easy loading of heavy machinery or oversize pallets. Crane systems can be used to load and unload crates without having to disassemble the container itself.[67] Open sides are also used for ventilating hardy perishables like apples or potatoes.

- Log cradles for cradling logs[68]

- Platform based containers such as:

- flat-rack and bolster containers, for barrels, drums, crates, and any heavy or bulky out-of-gauge cargo, like machinery, semi-finished goods or processed timber. Empty flat-racks can either be stacked or shipped sideways in another ISO container

- collapsible containers, ranging from flushfolding flat-racks to fully closed ISO and CSC certified units with roof and walls when erected.[70]

- trash containers, for carrying trash bags and cans to and from Recycling factories and landfills.

Containers for offshore use have a few different features, like pad eyes, and must meet additional strength and design requirements, standards and certification, such as the DNV2.7-1 by Det Norske Veritas, LRCCS by Lloyd's Register, Guide for Certification of Offshore Containers by American Bureau of Shipping and the International standard ISO10855: Offshore containers and associated lifting sets, in support of IMO MSC/Circ. 860[71]

A multitude of equipment, such as generators, has been installed in containers of different types to simplify logistics – see § Containerized equipment for more details.

Swap body units usually have the same bottom corner fixtures as intermodal containers, and often have folding legs under their frame so that they can be moved between trucks without using a crane. However they frequently do not have the upper corner fittings of ISO containers, and are not stackable, nor can they be lifted and handled by the usual equipment like reach-stackers or straddle-carriers. They are generally more expensive to procure.[72]

Specifications

editBasic terminology of globally standardized intermodal shipping containers is set out in standard:

- ISO 830:(1999) Freight containers – Vocabulary, 2nd edition; last reviewed and confirmed in 2016.

From its inception, ISO standards on international shipping containers, consistently speak of them sofar as 'Series 1' containers – deliberately so conceived, to leave room for another such series of interrelated container standards in the future.[nb 11]

Basic dimensions and permissible gross weights of intermodal containers are largely determined by two ISO standards:

- ISO 668:2013–2020 Series 1 freight containers—Classification, dimensions and ratings

- ISO 1496-1:2013 Series 1 freight containers—Specification and testing—Part 1: General cargo containers for general purposes

Weights and dimensions of the most common (standardized) types of containers are given below.[nb 12] Forty-eight foot and fifty-three foot containers have not yet been incorporated in the latest, 2020 edition of the ISO 668.[74] ISO standard maximum gross mass for all standard sizes except 10-ft boxes was raised to 36,000 kg or 79,000 lb per Amendment 1 on ISO 668:2013, in 2016.[75] Draft Amendment 1 of ISO 668: 2020 – for the eighth edition – maintains this.[76] Given the average container lifespan, the majority of the global container fleet have not caught up with this change yet.

Values vary slightly from manufacturer to manufacturer, but must stay within the tolerances dictated by the standards. Empty weight (tare weight) is not determined by the standards, but by the container's construction, and is therefore indicative, but necessary to calculate a net load figure, by subtracting it from the maximum permitted gross weight.

The bottom row in the table gives the legal maximum cargo weights for U.S. highway transport, and those based on use of an industry common tri-axle chassis. Cargo must also be loaded evenly inside the container, to avoid axle weight violations.[77] The maximum gross weights that U.S. railroads accept or deliver are 52,900 lb (24,000 kg) for 20-foot containers, and 67,200 lb (30,500 kg) for 40-foot containers,[78] in contrast to the global ISO-standard gross weight for 20-footers having been raised to the same as 40-footers in the year 2005.[79] In the U.S., containers loaded up to the rail cargo weight limit cannot move over the road, as they will exceed the U.S. 80,000 lb (36,000 kg) highway limit.[78]

| Container by common name (imperial) |

ISO (global) standard containers[80][81] | Common North American containers[82][83] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-foot standard height |

40-foot standard height |

40-foot high-cube |

45-foot high-cube |

48-foot high-cube |

53-foot high-cube | ||

| External dimensions |

Length | 19 ft 10+1⁄2 in 6.058 m |

40 ft 12.192 m |

45 ft 13.716 m |

48 ft 14.630 m |

53 ft 16.154 m | |

| Width | 8 ft 2.438 m |

8 ft 6 in 2.591 m | |||||

| Height | 8 ft 6 in 2.591 m |

9 ft 6 in 2.896 m |

9 ft 6 in 2.896 m | ||||

| Minimal interior dimensions |

Length | 19 ft 3 in 5.867 m |

39 ft 4+3⁄8 in 11.998 m |

44 ft 5+1⁄8 in 13.541 m |

47 ft 5 in 14.453 m |

52 ft 5 in 15.977 m | |

| Width | 7 ft 7+3⁄4 in 2.330 m |

8 ft 2 in 2.489 m | |||||

| Height | 7 ft 8+1⁄2 in 2.350 m |

8 ft 8+1⁄2 in 2.654 m |

8 ft 11 in 2.718 m | ||||

| Minimum door aperture |

Width | 7 ft 6 in 2.286 m |

8 ft 2 in 2.489 m | ||||

| Height | 7 ft 5 in 2.261 m |

8 ft 5 in 2.565 m |

8 ft 10 in 2.692 m | ||||

| Internal volume | 1,169 cu ft 33.1 m3 |

2,385 cu ft 67.5 m3 |

2,660 cu ft 75.3 m3 |

3,040 cu ft 86.1 m3 |

3,454 cu ft 97.8 m3 |

3,830 cu ft 108.5 m3 | |

| Common maximum gross weight |

30,480 kg 67,200 lb |

33,000 kg 73,000 lb |

30,480 kg 67,200 lb | ||||

| Empty (tare) weight (approximate) |

2,200 kg 4,850 lb |

3,800 kg 8,380 lb[84] |

3,935 kg 8,675 lb[82][84] |

4,500 kg 10,000 lb[82] |

4,920 kg 10,850 lb |

5,040 kg 11,110 lb | |

| Common net load (approximate) |

28,280 kg 62,350 lb |

26,680 kg 58,820 lb |

26,545 kg 58,522 lb |

28,500 kg 62,800 lb |

25,560 kg 56,350 lb |

25,440 kg 56,090 lb | |

| ISO maximum gross mass |

36,000 kg 79,000 lb per ISO 668:2013, amendment 1 (2016)[75][76] |

Not standardized | |||||

| U.S. maximum legal truck weights |

80,000 lb (36,000 kg) overall maximum on Interstate highways / 84,000 lb (38,000 kg) (6 or more axles) on non-Interstate highways[85] | ||||||

| Triaxle chassis: 44,000 lb (20,000 kg)[77][78] |

Triaxle chassis: 44,500 lb (20,200 kg)[77][78] | ||||||

Other sizes

editAustralian RACE containers

editAustralian RACE containers are also slightly wider to optimise them for the use of Australia Standard Pallets, or are 41 ft (12.5 m) long and 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) wide to be able to fit up to 40 pallets.[86][87]

European pallet wide containers

editEuropean pallet wide (or PW) containers are minimally wider, and have shallow side corrugation, to offer just enough internal width, to allow common European Euro-pallets of 1.20 m (47+1⁄4 in) long by 0.80 m (31+1⁄2 in) wide,[88] to be loaded with significantly greater efficiency and capacity. Having a typical internal width of 2.44 m (96+1⁄8 in),[89] (a gain of ~10 centimetres (3+15⁄16 in) over the ISO-usual 2.34 m (92+1⁄8 in),[90] gives pallet-wide containers a usable internal floor width of 2.40 m (94+1⁄2 in), compared to 2.00 m (78+3⁄4 in) in standard containers, because the extra width enables their users to either load two Euro-pallets end on end across their width, or three of them side by side (providing the pallets were neatly stacked, without overspill), whereas in standard ISO containers, a strip of internal floor-width of about 33 centimetres (13 in) cannot be used by Euro-pallets.

As a result, while being virtually interchangeable:[89]

- A 20-foot PW can load 15 Euro-pallets – four more, or 36% better than the normal 11 pallets in an ISO-standard 20-foot unit

- A 40-foot PW can load 30 Euro-pallets – five more, or 20% better than the 25 pallets in a standard 40-foot unit, and

- A 45-foot PW can load 34 Euro-pallets – seven more, or 26% better than 27 in a standard 45-foot container.

Some pallet-wides are simply manufactured with the same, ISO-standard floor structure, but with the side-panels welded in, such that the ribs/corrugations are embossed outwards, instead of indenting to the inside.[91] This makes it possible for some pallet-wides to be just 2.462 m (96+7⁄8 in) wide,[89] but others can be 2.50 m (98+3⁄8 in) wide.[92]

The 45 ft (13.72 m) pallet-wide high-cube container has gained particularly wide acceptance, as these containers can replace the 13.6 m (44 ft 7+3⁄8 in) swap bodies that are common for truck transport in Europe. The EU has started a standardization for pallet wide containerization in the European Intermodal Loading Unit (EILU) initiative.[93]

Many sea shipping providers in Europe allow these on board, as their external width overhangs over standard containers are sufficiently minor that they fit in the usual interlock spaces in ship's holds,[91] as long as their corner-castings patterns (both in the floor and the top) still match with regular 40-foot units, for stacking and securing.

North American containers

editThe North American market has widely adopted containerization, especially for domestic shipments that need to move between road and rail transport.[94] While they appear similar to the ISO-standard containers, there are several significant differences: they are considered High-Cubes based on their 9 ft 6 in (2.90 m) ISO-standard height, their 102-inch (2.6 m) width matches the maximum width of road vehicles in the region but is 6 inches (15 cm) wider than ISO-standard containers,[95] and they are often not built strong enough to endure the rigors of ocean transport.[94]

48-foot containers

editThe first North American containers to come to market were 48 feet (15 m) long. This size was introduced by container shipping company American President Lines (APL) in 1986.[94] The size of the containers matched new federal regulations passed in 1983 which prohibited states from outlawing the operation of single trailers shorter than 48 feet long or 102 inches wide.[96] This size being 8 feet (2.44 m) longer and 6 inches (15 cm) wider has 29% more volume capacity than the standard 40-ft High-Cube,[97] yet costs of moving it by truck or rail are almost the same.

53-foot containers

editIn the late 1980s, the federal government announced it would once again allow an increase in the length of trailers to 53 feet (16 m) at the start of 1990. Anticipating this change, 53 foot containers were introduced in 1989. These large boxes have 60% more capacity than 40' containers, enabling shippers to consolidate more cargo into fewer containers.[97][98][99]

In 2007, APL introduced the first 53-foot ocean-capable containers designed to withstand voyages on its South China-to-Los Angeles service.[94] In 2013, APL stopped offering vessel space for 53-foot containers on its trans-Pacific ships.[100] In 2015 both Crowley and TOTE Maritime each announced the construction of their respective second combined container and roll-on/roll-off ships for Puerto Rico trade, with the specific design to maximize cubic cargo capacity by carrying 53-foot, 102-inch wide (2,591 mm) containers.[101][102] Within Canada, Oceanex offers 53-foot-container ocean service to and from Newfoundland.[103] 53-foot containers are also being used on some Asia Pacific international shipping routes.[73]

Canadian 60-foot containers

editIn April 2017, Canadian Tire and Canadian Pacific Railway announced deployment of what they claimed to be the first 60-foot intermodal containers in North America.[104] The containers are transportable on the road using specially configured trucks and telescoping trailers (where vehicle size limits permit it), and on the railway using the top positions of double-stack container cars.[105] According to initial projections, Canadian Tire believed it would allow them to increase the volume of goods shipped per container by 13%.[104] 5 years after the deployment of the containers, analyst Larry Gross observed that United States truck size regulations are more constraining than those in Canada, and predicted that for the foreseeable future, these larger containers would remain exclusive to Canada.[106]

Small containers

editThe ISO 668 standard has so far never standardized 10 ft (3 m) containers to be the same height as so-called "Standard-height", 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m), 20- and 40-foot containers. By the ISO standard, 10-foot (and previously included 5-ft and 61⁄2-ft boxes) are only of unnamed, 8-foot (2.44 m) height. But industry makes 10-foot units more frequently of 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) height,[90] to mix, match (and stack) better in a fleet of longer, 8 ft 6 in tall containers. Smaller units, on the other hand, are no longer standardized, leading to deviating lengths, like 8 ft (2.44 m) or 6+1⁄2 ft (1.98 m), with non-standard widths of 2.20 m / 86.6 in and 1.95 m / 76+3⁄4 in respectively, and non-standard heights of 2.26 m / 7 ft 5 in and 1.91 m / 6 ft 3.2 in respectively,[90] for storage or off-shore use.

U.S. military

editThe United States military continues to use small containers, strongly reminiscent of their Transporter and Conex boxes of the 1950s and 1960s. These mostly comply with (previous) ISO standard dimensions, or are a direct derivative thereof. Current terminology of the United States armed forces calls these small containers Bicon, Tricon and Quadcon, with sizes that correspond with (previous) ISO 668 standard sizes 1D, 1E and 1F respectively. These containers are of a standard 8 ft (2.44 m) height, and with a footprint size either one half (Bicon), one third (Tricon) or one quarter (Quadcon) the size of a standard 20-foot, one TEU container.[107][108][109] At a nominal length of 10 feet (3.05 m), two Bicons coupled together lengthwise match one 20-foot ISO container, but their height is 6 inches (152 mm) shy of the more commonly available 10-foot ISO containers of so-called 'standard' height, which are 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) tall. Tricons and Quadcons however have to be coupled transversely – either three or four in a row – to be stackable with twenty foot containers.[110] Their length of 8 ft (2.44 m) corresponds to the width of a standard 20-foot container, which is why there are forklift pockets at their ends, as well as in the sides of these boxes, and the doors only have one locking bar each. The smallest of these, the Quadcon, exists in two heights: 96 in (2.44 m) or 82 in (2.08 m).[111] Only the first conforms to ISO-668 standard dimensions (size 1F).

ABC bulk containers

editABC containers are small containers, typically 20 ft long and 5 ft high, used for hauling dense materials. The smaller size reduces the tare weight (as compared to using a half-full standard height container). They are normally shipped on specialized railroad flatcars, where 6 containers can be carried in the space of 4 standard containers.[112]

Japan: 12-foot containers

editIn Japan's domestic freight rail transport, most of the containers are 12 ft (3.66 m) long in order to fit Japan's unique standard pallet sizes.[113]

- Gallery: Small container size examples

-

12-foot (3.66 m) the 19D-type container used by JR Freight in Japan

-

U.S. Navy tractor moves Quadcon containers at Kin Red Port in Okinawa (2005)

-

U.S. Navy load Tricon containers into a Lockheed C-5 Galaxy transport aircraft (2006)

-

U.S. Navy moving a Bicon box. Note the forklift pockets only in the sides, not at the ends.

Reporting mark

editEach container is allocated a standardized ISO 6346 reporting mark (ownership code), four letters long ending in either U, J or Z, followed by six digits and a check digit.[114] The ownership code for intermodal containers is issued by the Bureau International des Containers (International container bureau, abbr. B.I.C.) in France, hence the name "BIC-Code" for the intermodal container reporting mark. So far there exist only four-letter BIC-Codes ending in "U".

The placement and registration of BIC Codes is standardized by the commissions TC104 and TC122 in the JTC1 of the ISO which are dominated by shipping companies. Shipping containers are labelled with a series of identification codes that includes the manufacturer code, the ownership code, usage classification code, UN placard for hazardous goods and reference codes for additional transport control and security.

Following the extended usage of pallet-wide containers in Europe the EU started the Intermodal Loading Unit (ILU) initiative. This showed advantages for intermodal transport of containers and swap bodies. This led to the introduction of ILU-Codes defined by the standard EN 13044 which has the same format as the earlier BIC-Codes. The International Container Office BIC agreed to only issue ownership codes ending with U, J or Z. The new allocation office of the UIRR (International Union of Combined Road-Rail Transport Companies) agreed to only issue ownership reporting marks for swap bodies ending with A, B, C, D or K – companies having a BIC-Code ending with U can allocate an ILU-Code ending with K having the same preceding letters. Since July 2011 the new ILU codes can be registered, beginning with July 2014 all intermodal ISO containers and intermodal swap bodies must have an ownership code and by July 2019 all of them must bear a standard-conforming placard.[115]

Handling

editContainers are transferred between rail, truck, and ship by container cranes at container terminals. Forklifts, reach stackers, straddle carriers, container jacks and cranes may be used to load and unload trucks or trains outside of container terminals. Swap bodies, sidelifters, tilt deck trucks, and hook trucks allow transfer to and from trucks with no extra equipment.

ISO-standard containers can be handled and lifted in a variety of ways by their corner fixtures, but the structure and strength of 45-foot (type E) containers limits their tolerance of side-lifting, nor can they be forklifted, based on ISO 3874 (1997).[116]

Transport

editContainers can be transported by container ship, truck and freight trains as part of a single journey without unpacking. Units can be secured in transit using "twistlock" points located at each corner of the container. Every container has a unique BIC code painted on the outside for identification and tracking, and is capable of carrying up to 20–25 tonnes. Costs for transport are calculated in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU).

Rail

editWhen carried by rail, containers may be carried on flatcars or well cars. The latter are specially designed for container transport, and can accommodate double-stacked containers. However, the loading gauge of a rail system may restrict the modes and types of container shipment. The smaller loading gauges often found in European railroads will only accommodate single-stacked containers. In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, there are sections of the rail network through which high-cube containers cannot pass, or can pass through only on well cars. On the other hand, Indian Railways runs double-stacked containers on flatcars under 25 kV overhead electrical wires. The wires must be at least 7.45 metres (24 ft 5 in) above the track. China Railway also runs double-stacked containers under overhead wires, but must use well cars to do so, since the wires are only 6.6 metres (21 ft 8 in) above the track.[117]

Sea

editAbout 90% of non-bulk cargo worldwide is transported by container, and the largest container ships can carry over 19,000 TEU (Twenty-Foot Equivalent, or how many 20 foot containers can fit on a ship). Between 2011 and 2013, an average of 2,683 containers were reported lost at sea.[118] Other estimates go up to 10,000; of these 10% are expected to contain chemicals toxic to marine life.[119] Various systems are used for securing containers on ships.[120][121] Losses of containers at sea are low.[122]

Air

editContainers can also be transported in planes, as seen within intermodal freight transport. However, transporting containers in this way is typically avoided due to the cost of doing such and the lack of availability of planes which can accommodate such awkwardly sized cargo.

There are special aviation containers, smaller than intermodal containers, called unit load devices.

Securing and security

editSecuring containers and contents

editThere are many established methods and materials for stabilizing and securing intermodal containers loaded on ships, as well as the internal cargo inside the boxes. Conventional restraint methods and materials such as steel strapping and wood blocking and bracing have been around for decades and are still widely used. Polyester strapping and lashing, and synthetic webbings are also common today. Dunnage bags (also known as "air bags") are used to keep unit loads in place.

Flexi-bags can also be directly loaded, stacked in food-grade containers. Indeed, their standard shape fills the entire ground surface of a 20 ft ISO container.

- Methods of securing containers or internal loads

-

Containers can be horizontally connected with lashing bridge fittings

-

Dockworkers securing containers on a ship with steel lashing bars and turnbuckles

-

Polyester lashing application

-

Polyester strapping and dunnage bag application

-

Application in container

Non-shipping uses

editContainerized equipment

editContainer-sized units are also often used for moving large pieces of equipment to temporary sites. Specialised containers are particularly attractive to militaries already using containerisation to move much of their freight around. Shipment of specialized equipment in this way simplifies logistics and may prevent identification of high value equipment by enemies. Such systems may include command and control facilities, mobile operating theatres[124] or even missile launchers[125] (such as the Russian 3M-54 Klub surface-to-surface missile).

Complete water treatment systems can be installed in containers and shipped around the world.[126]

Electric generators can be permanently installed in containers to be used for portable power.[127]

Repurposing

editHalf the containers that enter the United States leave empty.[128] Their value in the US is lower than in China, so they are sometimes used for other purposes. This is typically but not always at the end of their voyaging lives. The US military often used its Conex containers as on-site storage, or easily transportable housing for command staff and medical clinics.[129] Nearly all of the more than 150,000 Conex containers shipped to Vietnam remained in the country, primarily as storage or other mobile facilities.[26] Permanent or semi-permanent placement of containers for storage is common. A regular forty-foot container has about 4,000 kg (8,818 lb) of steel, which takes 8,000 kWh (28,800 MJ) of energy to melt down. Repurposing used shipping containers is increasingly a practical solution to both social and ecological problems.

Shipping container architecture employs used shipping containers as the main framing of modular home designs, where the steel may be an integrated part of the design, or be camouflaged into a traditional looking home. They have also been used to make temporary shops, cafes, and computer datacenters, e.g. the Sun Modular Datacenter.

Intermodal containers are not strong enough for conversion to underground bunkers without additional bracing, as the walls cannot sustain much lateral pressure and will collapse.[citation needed] Also, the wooden floor of many used containers could contain some fumigation residues, rendering them unsuitable as confined spaces, such as for prison cells or bunkers. Cleaning or replacing the wood floor can make these used containers habitable, with proper attention to such essential issues as ventilation and insulation.

Single-time use

editThe City of Göttingen has deployed containers for the disablement of unexploded ordnance: either FIBCs filled with sand or IBCs filled with water. When the bomb squad performs controlled detonations, such prepared containers absorb shock and fragments.[130] This use requires level, load-bearing ground. The deformed containers are unsuitable for further circulation.

International standards

edit- ASTM D5728-00 Standard Practices for Securement of Cargo in Intermodal and Unimodal Surface Transport

- ISO 668:2013 Series 1 freight containers – Classification, dimensions and ratings

- ISO 830:1999 Freight containers – Vocabulary

- ISO 1161:1984 Series 1 freight containers – Corner fittings – Specification

- ISO 1496 – Series 1 freight containers – Specification and testing

- ISO 1496-1:2013 – Part 1: General cargo containers for general purposes

- ISO 1496-2:2008 – Part 2: Thermal containers

- ISO 1496-3:1995 – Part 3: Tank containers for liquids, gases, and pressurized dry bulk

- ISO 1496-4:1991 – Part 4: Non-pressurized container for dry bulk

- ISO 1496-5:1991 – Part 5: Platform and platform based containers

- ISO 2308:1972 Hooks for lifting freight containers of up to 30 tonnes capacity – Basic requirements

- ISO 3874:1997 Series 1 freight containers – Handling and securing

- ISO 6346:1995 Freight containers – Coding, identification and marking

- ISO 9897:1997 Freight containers – Container equipment data exchange (CEDEX) – General communication codes

- ISO/TS 10891:2009 Freight containers – Radio frequency identification (RFID) – Licence plate tag

- ISO 14829:2002 Freight containers – Straddle carriers for freight container handling – Calculation of stability

- ISO 17363:2007 Supply chain applications of RFID – Freight containers

- ISO/PAS 17712:2006 Freight containers – Mechanical seals

- ISO 18185-2:2007 Freight containers – Electronic seals

See also

edit- BBC Box – shipping container tracked by the BBC from September 2008 to April 2009

- Boxpark – Food/retail park made from shipping containers Mall

- Conflat

- Container chassis

- Container ship – Ship that carries cargo in intermodal containers

- Containerization – Intermodal freight transport system

- Container port design process

- Customs Convention on Containers – 1956 United Nations and International Maritime Organization treaty

- Double-stack rail transport

- GWR Container – British railway company's goods containers

- Inter-box connector

- Intermediate bulk container – Industrial-grade storage and transport container for fluids and solids

- Logistics Vehicle System – American military vehicle family

- MIL-STD-129 – military standard of the United States of America

- New York Central container

- RACE – shipping container

- Re:START – Temporary mall in Christchurch, New Zealand Mall

- Re-use – Heavy duty container used for shipping

- Roller container

- Roll trailer – auxiliary vehicle used to transport heavy goods

- SECU – Stora Enso Cargo Unit, a type of shipping container

- Shipping container – Heavy duty container used for shipping

- Stowage plan for container ships – Methods of organizing and loading containers

- Unit load – Size of assemblage into which individual items are combined for ease of storage & handling

Notes

edit- ^ Up from an estimated 18.6 million in 2011[8]

- ^ 8 ft 6 in length, 6 ft 3 in width and 6 ft 10+1⁄2 in height, and 9000 lb capacity[20][21]

- ^ Some sources also mention a 12-foot version.[24][25]

- ^ The Containerisation International Market Analysis Report: World Container Census 2012, and the Drewry Maritime Research report: Container Census 2012[43]

- ^ Originally "COR-TEN", a trademark of U.S. Steel Corporation

- ^ Using "standard" to mean "standard height", as intended within the ISO 668 standard,[46] as opposed to meaning "dry van" or "general purpose" container.[6]

- ^ Up from an estimated 34.5 million TEU in 2013[5]

- ^ Heavy 1 TEU containers are habitually stacked low in a vessel, both for the stability of a ship (keep the center of gravity low), as well as being often used under long term contracts, providing financial stability.[59]

- ^ Infrequently there are two sets,[60] an outer set which may be used for loaded handling, and an inner set only for unloaded handling, by smaller forklifts.[61]

- ^ Frequently used abbreviations for the most common ISO 6346 types are: GP (General Purpose), HC / HQ (High Cube), OT (Open Top), RF (Refrigerated), RK (Rack) and TK (Tank).[64]

- ^ The term "Series 1" in the standards' names expresses the interrelated nature of the standards, leaving room for another such series in the future. In 2012, Michel Hennemand, president of the International Container Bureau (BIC), and chair of ISO Technical committee 104, subcommittee SC 1: General purpose containers, asked whether the time has come to develop a new series of standards on containers (Series 2), to accommodate new sizes like American 53-foot and European Pallet-wide containers. A new series which, given the significant investments required by the industry, would replace the current series of standards (series 1) in the next 20 or 25 years.[73]

- ^ Forty-five-foot containers were not standardized by the ISO until the 2005 Amendment No. 2 to the ISO 668:1995 standard.[46]

References

edit- ^ Lewandowski, Krzysztof (2016). "Growth in the Size of Unit Loads and Shipping Containers from Antique to WWI". Packaging Technology and Science. 29 (8–9): 451–478. doi:10.1002/pts.2231. ISSN 1099-1522. S2CID 113982441.

- ^ a b c d Jean-Paul Rodrigue. "World Container Production, 2007". The Geography of Transport Systems. Hofstra University. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "M: MILVAN : military van (container)". Military Dictionary. MilitaryFactory.com. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

Military-owned, demountable container, conforming to US and international standards, operated in a centrally controlled fleet for movement of military cargo. Also called MILVAN.

- ^ "NSN: 8145-01-C00-8991 (CONTAINER SHIPPING AND STORAGE: 20 FT MILVAN)". ArmyProperty.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Global Container Fleet". www.worldshipping.org. World Shipping Council. 2013. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "World Container Fleet Overview". csiu.co. CSI Container Services International. January 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Container sizes". Shipsbusiness.com. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ a b Container Supply Review (PDF) (Report). World Shipping Council. May 2011. p. 1. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ "Container Shipping – Statistics & Facts". Statista.com. Statista Inc. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Global Trade – World Shipping Council

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions - Modeling Eras". 14 August 2015. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015.

- ^ Ripley, David (1993). The Little Eaton Gangway and Derby Canal (Second ed.). Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-431-8.

- ^ Essery, R. J, Rowland. D. P. & Steel W. O. British Goods Wagons from 1887 to the Present Day. Augustus M. Kelly Publishers. New York. 1979 p. 92 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Lewandowski, Krzysztof (2014). "Czechoslovak activity to prepare European norms for containers before the Second World War" (PDF). Acta Logistica. 1 (4): 1–7. doi:10.22306/al.v1i4.25. ISSN 1339-5629.

- ^ M.K. "Vorläufer der heutigen Container: pa, BT und B900" [Predecessors of today's containers: pa, BT and B900]. MIBA (in German) (Special 54): 12–19. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Nico Spilt. "Laadkistvervoer – Langs de rails" [Loading bin transport] (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Lewandowski, Krzysztof (2014). "Wymagania Organizacyjne Stosowania Systemu ACTS" [Organizational Requirements Use the ACTS System] (PDF). Pojazdy Szynowe (in Polish). 2: 1–14. ISSN 0138-0370.

- ^ Intermodal Marine Container Transportation: Impediments and Opportunities, Issue 236 // National Research Council: The container revolution (page 18): "This [Army] box in turn served as a model for the small containers that most major ship operators began using during the late 1940s and early 1950s. These however, were mainly loaded and unloaded at the docks, and not used intermodally."

- ^ "History & Development of the Container – The 'Transporter', predecessor to the CONEX". www.transportation.army.mil. U.S. Army Transportation Museum. 15 May 2013. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Heins, Matthew (2013). "2" (PDF). The Shipping Container and the Globalization of American Infrastructure (dissertation). University of Michigan. p. 15. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Levinson, Marc (2006). "Chapter 7: Setting the Standard". The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-691-12324-0. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ a b van Ham, van Ham & Rijsenbrij (2012), p. 8.

- ^ Monograph 7: Containerization (1970), p. 10, "The dimensions of the CONEX II are 75 by 82+1⁄2 by 102 in. The CONEX container is a metal reusable shipping box. The most common type has a 295-cu. ft. capacity, is about 8+2⁄2 by 6 by 7 ft, and can carry 9,000 lbs. The dimensions of the Half-CONEX or CONEX I container are 75 by 82+1⁄2 by 51 in."

- ^ Flanagan, Robert (2011). "Fleeing G.o.D.". Falloff. AuthorHouse. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4670-7295-3.

- ^ Michael J. Everhart (7 July 2014). "My Vietnam Tour – 1970". Retrieved 21 July 2015.

CONEX ... container that ... was about 7' high by 8' wide and about 12' long...

- ^ a b Monograph 7: Containerization (1970), pp. 9–11.

- ^ Levinson, Marc. "Chapter 1: The World the Box Made". The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger. Princeton University Press. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Gittins, Ross (12 June 2006). "How the invention of a box changed our world". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ van Ham, van Ham & Rijsenbrij (2012), p. 14.

- ^ van Ham, van Ham & Rijsenbrij (2012), p. 18.

- ^ van Ham, van Ham & Rijsenbrij (2012), p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Heilweil, Rebecca (14 December 2021). "The history of the metal box that's wrecking the supply chain". Vox.

- ^ Cudahy, Brian J. (September–December 2006). "The Containership Revolution: Malcom McLean's 1956 Innovation Goes Global" (PDF). TR News. No. 246. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ van Ham, van Ham & Rijsenbrij (2012), p. 26.

- ^ Bartsch, Butsri. "Sea freight – somehow antique yet modern!". Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "International Convention for Safe Containers (CSC) – Adoption: 2 December 1972; Entry into force: 6 September 1977". International Maritime Organisation. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ International Convention for Safe Containers Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Geneva, 2 December 1972)

- ^ a b c "NLRB v. Longshoremen, 447 U.S. 490" – via Admiralty and Maritime Law Guide.

- ^ a b c "NLRB v. Longshoremen, 447 U.S. 490" – via Justia: U.S. Supreme Court.

- ^ Partners, McAlinden Research (16 November 2020). "Shipping Container Shortage Could Last Until Next Year, Boosting Container Leasing Stocks". McAlinden Research Partners. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ cameronc86 (31 December 2020). "Container Shortage – The Reasons Behind It". ClearFreight. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Shipping companies box clever to overcome container shortages". The National. 9 November 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "World Container Fleet - CSI Container Services International". Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Shipping Container Homes Globally". Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "Miles to Go - Running Green content from Fleet Owner". 26 July 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015.

- ^ a b ISO 668:1995 Series 1 freight containers – Classification, dimensions and ratings – AMENDMENT 2: 45' containers (Technical report). ISO. 2005. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "40ft High Cubes set to Dominate the Container Equipment Market". Drewry Shipping Consultants. 18 June 2014. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ a b c "Composition of the Global Fleet of Containers, 2008". The Geography of Transport Systems. Hofstra University. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Section 3.1 Container design". Container Handbook. GDV. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ ISO 1496-1: Series 1 Freight Containers – Specification and Testing (PDF) (Technical report). ISO. 1990. pp. 4–5. Part 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2014.

- ^ Jean-Paul Rodrigue (2013). "Evolution of Containerships". The Geography of Transport Systems. Hofstra University. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ "The Triple-E A larger-than-life puzzle". 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Hammond, Richard. Episode 4: Mega Ship. Big. Event occurs at 1:23. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "GTRI Develops New Technologies to Secure Cargo Containers". PhysOrg.com. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ "The 20 Foot Shipping Container". Shipping-container-housing.com. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Thanh Do Container". thanhdocontainer.vn.

- ^ a b c Wackett, Mike (7 July 2015). "Price of new containers at a 10-year low, putting pressure on leasing companies". The Loadstar. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Upply is Using Data to Build a New Logistics Market: Here's How | MongoDB News

- ^ a b c d Ricqles, Jerome de (6 May 2019). "Containerized sea freight: is it time to switch from TEU to FEU?". Upply Transportation and Logistics Analysis. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ U.S. Army 20-ft ISO container in Pohang, South Korea, 2013 Archived 22 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ISO 1496-1: Series 1 Freight Containers – Specification and Testing (PDF) (Technical report). ISO. 1990. pp. 8, 13, 20. Part 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2014.

- ^ ISO:668 (E) (2013), p. 4.

- ^ "Selecting a Container" (PDF). CMA CGM Group. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ ISO Container Type Group.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Garmentainers". OOCL.com. Orient Overseas Container Line. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010.

- ^ "DB Schenker Logistics offers new solution for garments on hangers | 3PL". 3plnews.com. 7 July 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Jacob, Munden (14 August 2018). "Why Open-Top Containers Dominate the Glass Industry and How to Use Them To Streamline Your Shipping". Barrett Ltd. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ Log cradle

- ^ "COSCO develops tech to transform pulp ship into a car carrier". 22 August 2022.

- ^ 4FOLD – Foldable Container Archived 26 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Standard for Certification No.2.7-1 – Offshore Containers_April 2006 Archived 22 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Economic Analysis of Proposed Standardisation And Harmonisation Requirements" (PDF). ICF Consulting, Ltd. 13 October 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2010.

- ^ a b Hennemand, Michel (April 2012). "Containers – Talk about a revolution !". ISO Focus+. 3 (4): 21–22. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ [standard.https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/81611/5d7c564c8da2423e80fb95fbbdfeb70f/ISO-668-2020-DAmd-1.pdf ISO 668:2020 Preview (pdf)]

- ^ a b Sub-committee on Carriage of Cargoes and Containers (5 July 2019). Discrepancy in container stacking strength requirements between the pertinent ISO Standard and the Convention for Safe Containers (CSC) (PDF) (6th session; Agenda item 13 ed.). International Maritime Organization. pp. 1–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b Draft Amendment ISO 668:2020/DAM 1

- ^ a b c Container Weight: Overweight container guide – UK P&I Club.htm

- ^ a b c d Size and weight limit laws – TechnoGroup USA

- ^ ISO 668:1995 Series 1 freight containers – Classification, dimensions and ratings – AMENDMENT 1 (Technical report). ISO. 15 September 2005. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "ISO 668:2020 Series 1 freight containers — Classification, dimensions and ratings". ISO. 19 November 2024.

- ^ "ISO 668:2013(E)". Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Georgia Storage Containers: Specifications".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "53ft High Cube Container | 53' High Cube Container". Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ a b Shipping Container Dimensions – Container Container

- ^ Compilation of Existing State Truck Size and Weight Limit Laws – Appendix A State Truck Size and Weight Laws – Federal Highway Administration

- ^ 41ft Refrigerated Container | Up to 40 temp-controlled pallets

- ^ SCF: 41ft Refrigerated Container brochure.pdf

- ^ "Standard Shipping Containers". Container container. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Pallet wide containers – ShippingAndFreightResource.com

- ^ a b c Shipping Container Dimensions - Container Container.com

- ^ a b "gesu4710896.jpg". Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 2012-04-22.

- ^ Photo of 45-foot Cobelfret containers, with markings warning of their 2.5 metres width, as well as their 9'6'' height

- ^ Frederik Hallbjörner; Claes Tyrén (2004). "Possible consequences of a new European container standard (EILU)" (PDF). master thesis.

- ^ a b c d Crowe, Paul (2 November 2007). "APL Introduces 53 Foot Ocean Containers". Export Logistics Guide. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ "Container Dimensions 48' and 53'". PNW Equipment. Archived from the original on 5 October 2014.

- ^ Blaszak, Michael W. (1 May 2006). "Intermodal equipment". Trains Magazine. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ a b Jean-Paul Rodrigue (2006). "Carrying Capacity of Containers (in cubic feet)". The Geography of Transport Systems. Hofstra University. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ "53ft High Cube Container | 53' High Cube Container". Container Technology, Inc. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Joiner, Eric (5 November 2007). "Big Boxes bring Big Questions –". Freightdawg.com. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ JOC staff (15 March 2013). "APL Abandons 53-Foot Ocean Containers". The Journal of Commerce. Newark, New Jersey. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Construction Begins on Crowley's Second Commitment Class ConRo Ship for Use in the Puerto Rico Trade". Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide. Piraeus, Greece. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ "Containers for world's first LNG-powered container ships arrive at Jaxport". Jacksonville, Florida: Jacksonville Port Authority. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ "Oceanex Invests $8 Million to Expand its Refrigerated Services". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ a b Canadian Pacific and Canadian Tire Corporation Deploy North America's First 60-foot Intermodal Container, 27 April 2017, archived from the original on 11 May 2017, retrieved 3 May 2017

- ^ Menzies, James (22 December 2016), "Canadian Tire's push for 60", TruckNews.com, archived from the original on 26 December 2016, retrieved 7 November 2024,

McKenna has been pursuing the use of 60-ft. containers for several years now. It began as an idea to transition to 57-ft. containers, capable of accommodating two additional pallets, but he upped the ante when he saw another retailer was pulling a 60-ft. trailer on Ontario roads.

- ^ Gunnoe, Chase (17 November 2022), "Analysis: Canada's 60-foot container will likely stay north of the border", Trains website, archived from the original on 26 February 2024, retrieved 7 November 2024,

It's been five years since Canadian Pacific and retail giant Canadian Tire Corp. unveiled North America's first 60-foot intermodal container, and intermodal analyst Larry Gross says the larger container type is probably going to remain exclusive to Canada for the foreseeable future.

- ^ Bicon Transport Storage Units – Charleston Marine Containers Inc. Archived 8 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tricon Dry Freight Container – Maloy Mobile Storage Archived 11 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quadcon Dry Freight Container – Maloy Mobile Storage Archived 11 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ A 20-foot module of USAU containers. Archived 24 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quadcon and Tricon – Maloy Mobile Storage Archived 14 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Specialty Intermodal Cars". Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Wisinee Wisetjindawat; Hiroki Oiwa; Motohiro Fujita (2015). "Rare Mode Choice in Freight Transport: Modal Shift from Road to Rail" (PDF). Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies. 11. doi:10.11175/easts.11.774. S2CID 112515172. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Defense Transportation Regulation –Part VI" (PDF). Chapter 603: Intermodal Container Coding and Marking. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ "New markings of intermodal loading units in Europe" (PDF). International Union of Combined Road-Rail Transport Companies. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ TandemLoc – ISO Container Information Archived 30 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Raghvendra, Rao (26 August 2008). "Rlys reaches higher, sets world record". IndianExpress.com. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "World Shipping Council Containers Lost at Sea 2014 Update" (PDF). 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Scientists to study effects of shipping containers lost at sea". 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Container Handbook".

- ^ "How Shipping Containers are Stacked on Cargo Ships - American Trailer Rentals". 12 August 2019.

- ^ "The securing of containers on deck on a container ship – Transport Informations Service".

- ^ Hammelmann Diesel

- ^ ""operating Room in a Box" Unfolds". 9 September 2004. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ^ Correspondent, Thomas Harding (25 April 2010). "A cruise missile in a shipping box on sale to rogue bidders". Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Water treatment in container". Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) pg3 - ^ "No. 2879: Empty Shipping Containers". www.uh.edu.

- ^ "Glossary of Military Terminology". Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Göttingen: 4 World War II bombs prompt evacuation". Deutsche Welle. 31 January 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

Bomb disposal experts set up protective barricades around the site, including stacked shipping containers filled with special water balloons to absorb the explosion.

- van Ham, Hans; van Ham, J.C.; Rijsenbrij, Joan (2012). Development of Containerization. Amsterdam: IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-6149-9146-5. Retrieved 1 May 2020. page 8, page 14, page 18, page 20, page 26.

- Monograph 7: Containerization (PDF) (Report). Logistic Support in the Vietnam Era. US DoD Joint Logistics Review Board. 15 December 1970. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

Further reading

edit- Donovan, Arthur & Bonney, Joseph. The Box That Changed the World, East Windsor, New Jersey, Commonwealth Business Media, 2006 ISBN 978-1-891131-95-0

- George, Rose. Ninety Percent of Everything: Inside Shipping, the Invisible Industry That Puts Clothes on Your Back, Gas in Your Car, and Food on Your Plate (2013), describes typical sea voyage excerpt and text search

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Freight containers, Volume 34 of ISO standards handbook, International Organization for Standardization, 4th edition, 2006. ISBN 92-67-10426-8

- Levinson, Marc. The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-691-12324-1 excerpt and text search