Abdul Ghaffār Khān (Pashto: عبدالغفار خان; 6 February 1890 – 20 January 1988), also known as Bacha Khan (Pashto: باچا خان) or Badshah Khan (بادشاه خان, 'King of Chiefs'), was an Indian independence activist from the North-West Frontier Province, and founder of the Khudai Khidmatgar resistance movement against British colonial rule in India.[3]

Fakhr-e-Afghan Sarhadi Gandhi Abdul Ghaffar Khan | |

|---|---|

عبدالغفار خان | |

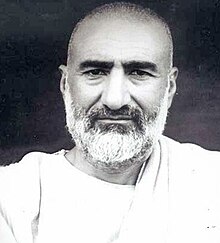

Ghaffar Khan c. 1940s | |

| Born | 6 February 1890 |

| Died | 20 January 1988 (aged 97) Peshawar, North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan |

| Resting place | Jalalabad, Afghanistan |

| Nationality |

|

| Education | Aligarh Muslim University |

| Title | Badshah Khan/Badshah Khan[2] |

| Political party |

|

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

| Spouses | Meharqanda Kinankhel

(m. 1912–1918)Nambata Kinankhel

(m. 1920–1926) |

| Children | 5, including |

| Parent | Abdul Bahram Khan (father) |

| Relatives | Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan (brother) |

| Awards |

|

He was a political and spiritual leader known for his nonviolent opposition and lifelong pacifism; he was a devout Muslim and an advocate for Hindu–Muslim unity in the subcontinent.[4] Due to his similar ideologies and close friendship with Mahatma Gandhi, Khan was nicknamed Sarhadi Gandhi (सरहदी गांधी, 'the Frontier Gandhi').[5][6] In 1929, Khan founded the Khudai Khidmatgar, an anti-colonial nonviolent resistance movement.[7] The Khudai Khidmatgar's success and popularity eventually prompted the colonial government to launch numerous crackdowns against Khan and his supporters; the Khudai Khidmatgar experienced some of the most severe repression of the entire Indian independence movement.[8]

Khan strongly opposed the proposal for the Partition of India into the Muslim-majority Dominion of Pakistan and the Hindu-majority Dominion of India, and consequently sided with the pro-union Indian National Congress and All-India Azad Muslim Conference against the pro-partition All-India Muslim League.[9][10][11] When the Indian National Congress reluctantly declared its acceptance of the partition plan without consulting the Khudai Khidmatgar leaders, he felt deeply betrayed, telling the Congress leaders "you have thrown us to the wolves."[12] In June 1947, Khan and other Khudai Khidmatgar leaders formally issued the Bannu Resolution to the British authorities, demanding that the ethnic Pashtuns be given a choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan, which was to comprise all of the Pashtun territories of British India and not be included (as almost all other Muslim-majority provinces were) within the state of Pakistan—the creation of which was still underway at the time. However, the British government refused the demands of this resolution.[13][14] In response, Khan and his elder brother, Abdul Jabbar Khan, boycotted the 1947 North-West Frontier Province referendum on whether the province should be merged with India or Pakistan, objecting that it did not offer options for the Pashtun-majority province to become independent or to join neighbouring Afghanistan.[15][16]

After the Partition of India by the British government, Khan pledged allegiance to the newly created nation of Pakistan, and stayed in the now-Pakistani North-West Frontier Province; he was frequently arrested by the Pakistani government between 1948 and 1954.[17][18] In 1956, he was arrested for his opposition to the One Unit program, under which the government announced its plan to merge all the provinces of West Pakistan into a single unit to match the political structure of erstwhile East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh). Khan was jailed or in exile during some years of the 1960s and 1970s. He was awarded Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, by the Indian government in 1987.

Following his will upon his death in Peshawar in 1988, he was buried at his house in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. Tens of thousands of mourners attended his funeral including Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah, marching through the Khyber Pass from Peshawar towards Jalalabad. It was marred by two bomb explosions that killed 15 people; despite the heavy fighting at the time due to the Soviet–Afghan War, both sides, namely the Soviet–Afghan government coalition and the Afghan mujahideen, declared an immediate ceasefire to allow Khan's burial.[19] He was given military honors by the Afghan government.

Early years

editAbdul Ghaffar Khan was born on 6 February 1890 into a prosperous Sunni Muslim Muhammadzai Pashtun family from Utmanzai, Hashtnagar; they lived by the Jindee-a, a branch of the Swat River, in what was then British India's Punjab province.[1][9][20] His father, Abdul Bahram Khan, was a land owner in Hashtnagar. Khan was the second son of Bahram to attend the British-run Edward's Mission School, which was the only fully-functioning school in the region and which was administered by Christian missionaries. At school, Khan did well in his studies, and was inspired by his mentor, Reverend Wigram, into seeing the crucial role education played in service to the local community. In his tenth and final year of secondary school, he was offered a highly prestigious commission in the Corps of Guides regiment of the British Indian Army. Khan declined due to his observational feelings that even Guides' Indian officers were still second-class citizens in their own nation. He subsequently followed through with his initial desire to attend university, and Reverend Wigram (Khan's teacher) offered him the opportunity to follow his brother, Abdul Jabbar Khan, to study in London, England. After graduating from Aligarh Muslim University, Khan eventually received permission from his father to travel to London. However, his mother wasn't willing to let another son go to London, so he began working on his father's lands in the process of figuring out his next steps.[21]

At the age of 20 in 1910, Khan opened a madrasa in his hometown of Utmanzai. In 1911, he joined the independence movement of the Pashtun activist Haji Sahib of Turangzai. By 1915, the British colonial authorities had shut down Khan's madrasa, deeming its pro-Indian independence activism to be a threat to their authority.[22] Having witnessed the repeated failure of Indian revolts against British rule, Khan decided that social activism and reform would be more beneficial for the ethnic Pashtuns. This led to the formation of the Anjuman-e Islāh-e Afghānia (Pashto: انجمن اصلاح افاغنه, 'Afghan Reform Society') in 1921, and the youth movement Pax̌tūn Jirga (پښتون جرګه, 'Pashtun Assembly') in 1927. After Khan's return from the Islamic Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Hejaz−Nejd (present-day Saudi Arabia) in May 1928, he founded the Pashto-language monthly political journal Pax̌tūn (پښتون, 'Pashtun'). Finally, in November 1929, Khan founded the Khudāyī Khidmatgār (خدايي خدمتګار, 'Servants of God') movement, which would strongly advocate for the end of British colonial rule and establishment of a unified and independent India.[8]

Ghaffar "Badshah" Khan

editIn response to his inability to continue his own education, Bacha Khan turned to helping others start theirs. Like many such regions of the world, the strategic importance of the newly formed North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan), as a buffer for the British Raj from Russian influence was of little benefit to its residents. Opposition to British colonial rule, the authority of the mullahs, and an ancient culture of violence and vendetta prompted Bacha Khan to want to serve and uplift his fellow men and women by means of education. At 20 years of age, Bacha Khan opened his first school in Utmanzai. It was an instant success and he was soon invited into a larger circle of progressively minded reformers.

While he faced much opposition and personal difficulties, Bacha Khan worked tirelessly to organise and raise the consciousness of his fellow Pashtuns. Between 1915 and 1918 he visited 500 villages in all part of the settled districts of NWFP. It was in this frenzied activity that he had come to be known as Badshah (Bacha) Khan ("King of Chiefs").[21]

Being a secular Muslim he did not believe in religious divisions. He married his first wife Meharqanda in 1912; she was a daughter of Yar Mohammad Khan of the Kinankhel clan of the Mohammadzai tribe of Razzar, a village adjacent to Utmanzai. They had a son in 1913, Abdul Ghani Khan, who would become a noted artist and poet. Subsequently, they had another son, Abdul Wali Khan (17 January 1917 – 2006), and daughter, Sardaro. Meharqanda died during the 1918 influenza epidemic. In 1920, Bacha Khan remarried; his new wife, Nambata, was a cousin of his first wife and the daughter of Sultan Mohammad Khan of Razzar. They had a daughter, Mehar Taj (25 May 1921 – 29 April 2012),[23] and a son, Abdul Ali Khan (20 August 1922 – 19 February 1997). Tragically, in 1926 Nambata died early as well from a fall down the stairs of the apartment where they were staying in Jerusalem.[20]

Khudai Khidmatgar

editIn time, Bacha Khan's goal came to be the formulation of a united, independent, secular India. To achieve this end, he founded the Khudai Khidmatgar ("Servants of God"), commonly known as the "Red Shirts" (Surkh Pōsh), during the 1920s.

The Khudai Khidmatgar was founded on a belief in the power of Gandhi's notion of Satyagraha, a form of active non-violence as captured in an oath. He told its members:

I am going to give you such a weapon that the police and the army will not be able to stand against it. It is the weapon of the Prophet, but you are not aware of it. That weapon is patience and righteousness. No power on earth can stand against it.[24]

The organisation recruited over 100,000 members and became influential in the independence movement for their resistance to the colonial government. Through strikes, political organisation and non-violent opposition, the Khudai Khidmatgar were able to achieve some success and came to dominate the politics of NWFP. His brother, Dr. Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan (known as Dr. Khan Sahib), led the political wing of the movement, and was the Chief Minister of the province (from 1937 and then until 1947 when his government was dismissed by Mohammad Ali Jinnah of the Muslim League).

Kissa Khwani Massacre

editOn 23 April 1930, Bacha Khan was arrested during protests arising out of the Salt Satyagraha. A crowd of Khudai Khidmatgar gathered in Peshawar's Kissa Khwani (Storytellers) Bazaar. The colonial government ordered troops to open fire with machine guns on the unarmed crowd, killing an estimated 200–250.[25] The Khudai Khidmatgar members acted in accord with their training in non-violence under Bacha Khan, facing bullets as the troops fired on them.[26] Two platoons of the Garhwal Rifles regiment under Chandra Singh Garhwali refused to fire on the non-violent crowd. They were later court-martialled and sentenced to a variety of punishments, including life imprisonment.[citation needed]

Bacha Khan and the Indian National Congress

editBacha Khan forged a close, spiritual, and uninhibited friendship with Gandhi, the pioneer of non-violent mass civil disobedience in India. The two had a deep admiration towards each other and worked together closely till 1947.

Khudai Khidmatgar (servants of God) agitated and worked cohesively with the Indian National Congress (INC), the leading national organisation fighting for independence, of which Bacha Khan was a senior and respected member. On several occasions when the Congress seemed to disagree with Gandhi on policy, Bacha Khan remained his staunchest ally. In 1931 the Congress offered him the presidency of the party, but he refused saying, "I am a simple soldier and Khudai Khidmatgar, and I only want to serve." He remained a member of the Congress Working Committee for many years, resigning only in 1939 because of his differences with the Party's War Policy. He rejoined the Congress Party when the War Policy was revised.

Bacha Khan was a champion of women's rights [dubious – discuss] and non-violence. He became a hero in a society dominated by violence; notwithstanding his liberal views, his unswerving faith and obvious bravery led to immense respect. Throughout his life, he never lost faith in his non-violent methods or in the compatibility of Islam and non-violence. He recognised as a jihad struggle with only the enemy holding swords. He was closely identified with Gandhi because of his non-violence principles and he is known in India as the 'Frontier Gandhi'. One of his Congress associates was Pandit Amir Chand Boambwal of Peshawar.

O Pathans! Your house has fallen into ruin. Arise and rebuild it, and remember to what race you belong.

— Ghaffar Khan[27]

The Partition

editKhan strongly opposed the partition of India.[9][10] Accused as being anti-Muslim by some politicians, Khan was physically assaulted in 1946, leading to his hospitalisation in Peshawar.[28] On 21 June 1947, in Bannu, a loya jirga was held consisting of Bacha Khan, the Khudai Khidmatgars, members of the Provincial Assembly, Mirzali Khan (Faqir of Ipi), and other tribal chiefs, just seven weeks before the partition. The loya jirga issueud the Bannu Resolution, which demanded that the Pashtuns be given a choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan composing all Pashtun territories of British India, instead of being made to join either India or Pakistan. However, the British refused to comply with the demand of this resolution.[13][14]

The Congress Party refused last-ditch compromises to prevent the partition, like the Cabinet Mission Plan and Gandhi's suggestion to offer the position of Prime Minister to Jinnah.

When the July 1947 NWFP Referendum over accession to Pakistan was held, Bacha Khan, the Khudai Khidmatgars, the then Chief Minister Khan Sahib, and the Indian National Congress Party boycotted the referendum. Some have argued that a segment of the population was barred from voting.[15]

Arrest and exile

editBacha Khan took the oath of allegiance to the new nation of Pakistan on 23 February 1948 at the first session of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly.[17][18]

He pledged full support to the government and attempted to reconcile with the founder of the new state Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Although initial overtures led to a successful meeting in Karachi, a follow-up meeting in the Khudai Khidmatgar HQ never materialised, allegedly due to the role of NWFP Chief Minister, Abdul Qayyum Khan Kashmiri, who told Jinnah that Bacha Khan was plotting his assassination.[29][30]

Following this, Bacha Khan formed Pakistan's first national opposition party, on 8 May 1948, the Pakistan Azad Party. The party pledged to play the role of constructive opposition and would be non-communal in its philosophy.

However, suspicions of his allegiance persisted and under the new Pakistani government, Bacha Khan was placed under house arrest without charge from 1948 till 1954. In 1954, Bacha Khan split with his elder brother Khan Sahib after the latter joined the Central Cabinet of Muhammad Ali Bogra as Minister for Communications. Released from prison, he gave a speech again on the floor of the National Assembly, this time condemning the massacre of his supporters at Babrra.[31]

I had to go to prison many a time in the days of the Britishers. Although we were at loggerheads with them, yet their treatment was to some extent tolerant and polite. But the treatment which was meted out to me in this Islamic state of ours was such that I would not even like to mention it to you.[32]

He was arrested several times after late 1948. In 1956 he was arrested for opposing the One Unit Scheme.[33] The government attempted in 1958 to reconcile with him and offered him a ministry in the government, after the assassination of his brother, but he refused.[34] He remained in prison till 1957 only to be re-arrested in 1958 until an illness in 1964 allowed for his release.[35]

In 1962, Bacha Khan was named an "Amnesty International Prisoner of the Year". Amnesty's statement about him said, "His example symbolizes the suffering of upward of a million people all over the world who are prisoners of conscience."

In September 1964, the Pakistani authorities allowed him to go to the United Kingdom for treatment. During the winter, his doctor advised him to go to United States. He then went into exile to Afghanistan, he returned from exile in December 1972 to popular support, following the establishment of National Awami Party provincial governments in North West Frontier Province and Balochistan.

He was arrested by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's government at Multan in November 1973 and described Bhutto's government as "the worst kind of dictatorship".[36]

In 1984, increasingly withdrawing from politics, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.[37] He visited India and participated in the centennial celebrations of the Indian National Congress in 1985; he was awarded the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding in 1967[38] and later Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, in 1987.[39]

His final major political challenge was against the Kalabagh dam project, fearing that the project would damage the Peshawar valley. His hostility would eventually lead to the project being shelved after his death.[citation needed]

Death

editBacha Khan died in Peshawar in 1988 from complications of a stroke and was buried in his house at Jalalabad, Afghanistan.[40] Over 200,000 mourners attended his funeral, including the Afghan president Mohammad Najibullah. The then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi went to Peshawar, to pay his tributes to Bacha Khan despite the fact that General Zia ul-Haq attempted to stall his attendance citing security reasons. Additionally, the Indian government declared a five-day period of mourning in his honour.[39] Although he had been repeatedly imprisoned and persecuted, tens of thousands of mourners attended his funeral, described by one commentator as "a caravan of peace, carrying a message of love" from Pashtuns east of the Khyber to those on the west,[29] marching through the historic Khyber Pass from Peshawar to Jalalabad. This symbolic march was planned by Bacha Khan, to affirmatively demonstrate his dream of Pashtun unification and to help that dream live on after his death.[citation needed] A cease-fire was announced in the Afghan Civil War to allow the funeral to take place, even though it was marred by bomb explosions killing fifteen people.[19]

Pashtunistan

editAbdul Ghaffar Khan took an oath of allegiance to Pakistan in 1948 in the legislation assembly. When during his speech he was asked by the PM Liaquat Ali Khan about Pashtunistan, he replied that it was just a name for the Pashtun province in Pakistan, just as Punjab, Bengal, Sindh, and Baluchistan are the names of provinces of Pakistan as ethno-linguistic names,[41] However, this compromise was apparently contrary to what he believed in and strived for before partition: Pashtunistan as an independent state after the failure of the idea of a united India.

Later on in 1980, during an interview with an Indian journalist, Haroon Siddiqui, in Jalalabad, Abdul Ghaffar Khan said

The idea never helped us. In fact, it was never a reality. Successive Afghan governments just exploited it for their own political ends. It was only towards the end of his regime that Daoud Khan had stopped talking about it. And Taraki in the early part of his regime also didn't mention it. So when I met him, I thanked him for not raising the issue. But later, even he raised the issue because he wanted to continue the problem for Pakistan. Our people suffered greatly because of all this.

[42] He also said in the same interview that "I'll live here. I'm now (for all intents and purposes) an Afghan. I'm not even permitting my son, Khan Abdul Wali Khan, political leader of Pakistan's North West Frontier Province, to visit me because he'll insist that I go with him to Pakistan. But I don't want to go."

Family

editBacha Khan married his first wife Meharqanda in 1912; she was a daughter of Yar Mohammad Khan of the Kinankhel clan of the Mohammadzai tribe of Razzar, a village adjacent to Utmanzai. They had a son in 1913, Abdul Ghani Khan, who would become a noted artist and poet. Subsequently, they had another son, Abdul Wali Khan (17 January 1917 – 2006), and daughter, Sardaro. Meharqanda died during the 1918 influenza epidemic. In 1920, Bacha Khan remarried; his new wife, Nambata, was a cousin of his first wife and the daughter of Sultan Mohammad Khan of Razzar. They had a daughter, Mehar Taj (25 May 1921 – 29 April 2012),[23] and a son, Abdul Ali Khan (20 August 1922 – 19 February 1997). Tragically, in 1926 Nambata died early as well from a fall down the stairs of the apartment where they were staying in Jerusalem.[20]

Legacy

editBacha Khan's political legacy is renowned amongst Pashtuns[citation needed] and those in modern Republic of India as a leader of a non-violent movement. Within Pakistan, however, the vast majority of society have questioned his stance with the All India Congress over the Muslim League as well as his opposition to the partition of India and Jinnah. In particular, people have questioned where Bacha Khan's patriotism rests.

His eldest son Ghani Khan was a poet. Ghani Khan's wife, Roshan, was from a Parsi family and was the daughter of Nawab Rustam Jang, a prince of Hyderabad.[43] His second son, Abdul Wali Khan, was the founder and leader of the Awami National Party from 1986 to 2006, and was the Leader of the Opposition in the Pakistan National Assembly from 1988 to 1990.

His third son Abdul Ali Khan was non-political and a distinguished educator, and served as Vice-Chancellor of University of Peshawar. Ali Khan was also the head of Aitchison College in Lahore and Fazle Haq College in Mardan.

His niece Mariam married Jaswant Singh in 1939. Jaswant Singh was a young British Indian airforce officer and was Sikh by faith. Mariam later converted to Christianity.[44]

Mohammed Yahya, Education Minister of Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, was the only son-in-law of Bacha Khan.

Asfandyar Wali Khan is the grandson of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, and was the leader of the Awami National Party. The party was in power from 2008 to 2013.

Zarine Khan Walsh, who lives in Mumbai, is the granddaughter of Abdul Ghaffar Khan and was the second daughter of Abdul Ghaffar Khan's eldest son Abdul Ghani Khan.[45]

The All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind is chaired by Yasmin Nigar Khan, who claims to be the great-granddaughter of Abdul Ghaffar Khan.[46][47] Awami National Party leader Asfandyar Wali Khan rejected the claim, though a cultural ministry official clarified that Yasmin Nigar Khan was a descendant of Abdul Ghaffar Khan's "adopted" son.[45]

Salma Ataullahjan is the great-grandniece of Abdul Ghaffar Khan and a member of the Senate of Canada.

Film, literature and society

editIn 2008, a documentary, titled The Frontier Gandhi: Badshah Khan, a Torch for Peace, by film-maker and writer T.C. McLuhan, premiered in New York. The film received the 2009 award for Best Documentary Film at the Middle East International Film Festival (see film page).

In 1990, Abdul Kabeer Siddiqui of Indian National TV made a 30-minute English-language biographical documentary film on Badshah Khan, titled The Majestic Man. It was telecast on Doordarshan.

In Richard Attenborough's 1982 epic Gandhi, Bacha Khan was portrayed by Dilsher Singh.

In his home city of Peshawar, the Bacha Khan International Airport is named after him.

In his hometown Charsadda, the Bacha Khan University is named after him.

Bacha Khan was listed as one of 26 men who changed the world in a recent children's book published in the United States, alongside Tiger Woods and Yo-Yo Ma.[48] He also wrote an autobiography (1969), and has been the subject of biographies by Eknath Easwaran (see article) and Rajmohan Gandhi (see "References" section, below). His philosophy of Islamic pacifism was recognised by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, in a speech to American Muslims.[49]

In the Indian city of Delhi, the popular Khan Market is named in his honour, along with Ghaffar market in the Karol Bagh area of New Delhi.[50][51] In Mumbai, a seafront road and promenade in the Worli neighbourhood was named Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan Marg after him.

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ a b Manishika, Meena (2021). Biography of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan: Inspirational Biographies for Children. Prabhat Prakashan.

- ^ Ahmad, Aijaz (2005). "Frontier Gandhi: Reflections on Muslim Nationalism in India". Social Scientist. 33 (1/2): 22–39. JSTOR 3518159.

- ^ Hamling, Anna (16 October 2019). Contemporary Icons of Nonviolence. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-4173-3.

- ^ An American Witness to India's Partition by Phillips Talbot, (2007), Sage Publications ISBN 978-0-7619-3618-3

- ^ Service, Tribune News. "Uttarakhand journalist gave Frontier Gandhi title to Abdul Gaffar Khan, claims book". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Raza, Moonis; Ahmad, Aijazuddin (1990). An Atlas of Tribal India: With Computed Tables of District-level Data and Its Geographical Interpretation. Concept Publishing Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-8170222866.

- ^ Burrell, David B. (7 January 2014). Towards a Jewish-Christian-Muslim Theology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-118-72411-8.

- ^ a b Zartman, I. William (2007). Peacemaking in International Conflict: Methods & Techniques. US Institute of Peace Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-1929223664. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b c "Abdul Ghaffar Khan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ a b "Abdul Ghaffar Khan". I Love India. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ Qasmi, Ali Usman; Robb, Megan Eaton (2017). Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Idea of Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1108621236.

- ^ "Partition and Military Succession Documents from the U.S. National Archives".

- ^ a b Ali Shah, Sayyid Vaqar (1993). Marwat, Fazal-ur-Rahim Khan (ed.). Afghanistan and the Frontier. University of Michigan: Emjay Books International. p. 256.

- ^ a b H Johnson, Thomas; Zellen, Barry (2014). Culture, Conflict, and Counterinsurgency. Stanford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0804789219.

- ^ a b Meyer, Karl E. (2008). The Dust of Empire: The Race For Mastery in the Asian Heartland – Karl E. Meyer – Google Boeken. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-0786724819. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Was Jinnah democratic? — II". Daily Times. 25 December 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b Shah, Sayed Wiqar Ali. "Abdul Ghaffar Khan" (PDF). Baacha Khan Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ a b Christophe Jaffrelot (2015). The Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience. Oxford University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-19-023518-5.

- ^ a b "15 Killed at Afghan Rites for Pathan Leader". The New York Times. AP. 23 January 1988. p. Section 1, page 28.

- ^ a b c "Ghani Khan". Kyber Gateway. Archived from the original on 23 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Meyer, Karl E. (7 December 2001). "The Peacemaker of the Pashtun Past". The New York Times.

- ^ "Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan" (PDF). Baacha Khan Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Daughter of Bacha Khan passes away". ePeshawar. 27 April 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- ^ Nonviolence in the Islamic Context by Mohammed Abu Nimer 2004 Archived 1 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Habib, p. 56.

- ^ Johansen, p. 62.

- ^ Eknath Easwaran, Nonviolent Soldier of Islam: Badshah Khan: A Man to Match His Mountains (Nilgiri Press, 1984, 1999), p. 25.

- ^ "Abdul Ghaffar Khan, 98, a Follower of Gandhi." The New York Times, 21 January 1988.

- ^ a b Korejo, M.S. (1993) The Frontier Gandhi, his place in history. Karachi : Oxford University Press.

- ^ Azad, Abul Kalam (2005) [First published 1959]. India Wins Freedom: An Autobiographical Narrative. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 213–214. ISBN 81-250-0514-5.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan had several interviews with him at Karachi and at one stage it seemed that an understanding would be reached ... [Jinnah] planned to go to Peshawar to meet him ... This however did not materialise. Soon the political enemies of the Khan brothers poisoned Jinnah's mind against them. Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan ... was naturally opposed to any reconciliation between Jinnah and the Khan brothers. He therefore behaved in a way which made any understanding impossible.

- ^ Hassan, Syed Minhajul (1998). Babra Firing Incident: 12 August 1948. Peshawar: University of Peshawar.

- ^ Badshah Khan, Budget session of Assembly on 20 March 1954.

- ^ Abdul Ghaffar Khan(1958) Pashtun Aw Yoo Unit. Peshawar.

- ^ by Zaidi, Syed Afzaal Husain. "An Old episode recalled" 28 September 2005, Dawn.com

- ^ "Pakistan: The Frontier Gandhi" (18 January 1954). Time.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (1993) Zulfi Bhutto of Pakistan: His Life and Times. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507661-5

- ^ McKibben, William (24 September 1984). "The Talk of the Town: Notes and Comments". The New Yorker. pp. 39–40.

- ^ "List of the recipients of the Jawaharlal Nehru Award". ICCR website. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ a b Abdul Ghaffar Khan, 98, a Follower of Gandhi (21 January 1988) The New York Times. Retrieved 21 January 2008

- ^ Ron Tempest (21 June 1988). "Ghaffar Khan: 'Frontier Gandhi' of India". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Bukhari, Farigh (1991). Taḥrīk-i āzādī aur Bācā K̲h̲ān. Fiction House. p. 226.

- ^ "Everything in Afghanistan is done in the name of religion: Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan". India Today. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ Arbab, Safoora (2016). "Ghani Khan: A Postmodern Humanist Poet-Philosopher" (PDF). Sagar: A South Asia Research Journal. 24: 24–63, 30.

- ^ Banerjee, Mukulika (2001). The Pathan Unarmed: Opposition & Memory in the North West Frontier. James Currey Publishers. p. 185. ISBN 0852552734.

- ^ a b Sharma, Vinod (1 June 2016). "Ministry goofs up on Ghaffar Khan's 'kin'". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ "Frontier Gandhi's granddaughter urges Centre to grant citizenship to Pathans". The News International. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Bacha Khan's great-granddaughter says Pakistan was behind attack on university". The Khaama Press News Agency. 23 January 2016.

The great-granddaughter of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan or Bacha Khan says that Pakistan was behind the university attack in which students were butchered. She has rejected the claim of Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) that accepted responsibility for attack on Bacha Khan University, named after her great-grandfather, saying it was done by Islamabad to "vitiate the minds" of Pakistani Pashtuns against the people of Afghanistan. In an interview with Hindustan Times, Yasmin Nigar Khan, 42, who heads the All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind, has argued that if this is not the cause then, why would the Taliban attack the North West Frontier Province every time, instead of striking in the Punjab or Sindh provinces?

- ^ Cynthia Chin-Lee, Megan Halsey, Sean Addy (2006). Akira to Zoltán: twenty-six men who changed the world. Watertown, MA (US): Charlesbridge. ISBN 978-1-57091-579-6 (Badshah Khan is listed under the letter 'B', p. 5)

- ^ Muslim Media Network. (17 September 2009). Hillary Clinton hosts Iftar at State Department. Archived 2 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine last accessed 22 March 2010.

- ^ "Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan Market". Paprika Media Private Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ "My visits to Khan Market". Sify News. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

References

edit- Habib, Irfan (September–October 1997). "Civil Disobedience 1930–31". Social Scientist. 25 (9–10): 43–66. doi:10.2307/3517680. JSTOR 3517680.

- Johansen, Robert C. (1997). "Radical Islam and Nonviolence: A Case Study of Religious Empowerment and Constraint Among Pashtuns". Journal of Peace Research. 34 (1): 53–71. doi:10.1177/0022343397034001005. S2CID 145684635.

- Caroe, Olaf. 1984. The Pathans: 500 B.C–-A.D. 1957 (Oxford in Asia Historical Reprints)." Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-577221-0

- Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1969). My life and struggle: Autobiography of Badshah Khan (as narrated to K.B. Narang). Translated by Helen Bouman. Hind Pocket Books, New Delhi.

- Rajmohan Gandhi (2004). Ghaffar Khan: non-violent Badshah of the Pakhtuns. Viking, New Delhi. ISBN 0-670-05765-7.

- Eknath Easwaran (1999). Nonviolent Soldier of Islam: Ghaffar Khan, a man to match his mountains. Nilgiri Press, Tomales, CA. ISBN 1-888314-00-1

- Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan: A True Servant of Humanity by Girdhari Lal Puri pp. 188–190.

- Mukulika Banerjee (2000). Pathan Unarmed: Opposition & Memory in the North West Frontier. School of American Research Press. ISBN 0-933452-68-3

- Pilgrimage for Peace: Gandhi and Frontier Gandhi Among N.W.F. Pathans, Pyarelal, Ahmedabad, Navajivan Publishing House, 1950.

- Tah Da Qam Da Zrah Da Raza, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Mardan [Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa] Ulasi Adabi Tolanah, 1990.

- Thrown to the Wolves: Abdul Ghaffar, Pyarelal, Calcutta, Eastlight Book House, 1966.

- Faraib-e-Natamam , Juma Khan Sufi

External links

edit- Leake, Elisabeth (2015). "ʿAbd al-Ghaffār Khān". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Interview with Bacha Khan

- Baacha Khan Trust

- Columbia University pictures

- Photograph Collection