The GIO Building is a heritage-listed office tower located at 60-70 Elizabeth Street in the Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It was built during 1929. It is also known as the General Insurance Office Building; the GIO building, and was constructed as the Sun Building or the Sun Newspaper Building. The property is privately owned and was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

| GIO Building | |

|---|---|

The Elizabeth Street façade in 2013 | |

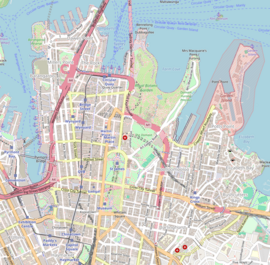

Location in Sydney central business district | |

| Former names | Sun Building Sun Newspaper Building |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Skyscraper |

| Architectural style | Interwar Skyscraper Gothic |

| Address | 60-70 Elizabeth Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′06″S 151°12′39″E / 33.8682479719°S 151.2108732860°E |

| Named for | Government Insurance Office (GIO) |

| Opened | 15 October 1929 |

| Renovation cost | A$12 million (1985) |

| Client | Sun Newspaper Limited |

| Owner | NGI Investments Pty Ltd |

| Technical details | |

| Material |

|

| Floor count | 10 |

| Lifts/elevators | 7 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Joseph Alexander Kethel |

| Architecture firm | Thomas Rowe and Sydney Moore Green |

| Main contractor | Concrete Constructions |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) | Keers Banks and Maitland |

| Official name | GIO Building; Sun Building |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Criteria | a., c., d., e. |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 683 |

| Type | Commercial Office/Building |

| Category | Commercial |

| References | |

| [1] | |

The GIO building was built in the Interwar Skyscraper Gothic style.

History

editThe early owners of the site

editThe land on which 60-70 Elizabeth Street stands comprises sections of three early land grants made in Section 40 of the City of Sydney. It includes land from part of Allotment 7, granted to Jacob Josephson on 5 April 1836, part of Allotment 18 granted to Francis Wilde (or Wild) on 14 May 1836 and part of Allotment 8 granted to Joseph Roberts on 29 December 1842, although all were in occupation for a number of years beforehand.[1]

The major part of the site consists of that portion located on the part of Allotment 7, one of several adjoining parcels of land granted to Jacob Josephson. Josephson was a jeweller by profession, a Jewish Christian who reached Sydney in May 1818 as a result of being convicted of having forged bank notes in his possession. He died in the first half of the 1840s, and his son Joshua Frey Josephson inherited his property, including Enmore House, in 1945.[1]

Joseph Josephson was born in 1815 in Hamburg, and arrived with his mother in Sydney in 1820. He displayed great musical talent and was teaching music by 1834. On 17 February 1844 he became a solicitor, the same year in which he was elected to the Sydney City Council to represent Cook Ward. In 1848 he became Mayor of Sydney as well as a justice of the peace, and on 9 June 1855 he was admitted to the New South Wales Bar Association. The following year he travelled to England, entered Lincoln's Inn and was called to the Bar in April 1859. On his return to Sydney he practiced as a barrister and in 1862 became a land titles commissioner under the newly introduced Real Properties Act. During this decade he was a director of the Australian Joint Stock Bank and invested in pastoral and city land. In 1868 he became solicitor general, but resigned from parliament in 1869 after his appointment as a district court judge. Josephson resigned in 1884 to devote more time to his private affairs, and died in January 1892. Lot 7, however, remained in the possession of the Josephson family until the beginning of the 1920s.[1]

Lot 8 appears to have been occupied by one Richard Roberts from July 1829 onwards, and was not associated with Joseph Roberts and also William Henry Roberts until September 1842. It remained in the possession of members of the Roberts family until 1874, when title to it was conveyed to John Starkey.[1]

The land granted to Francis Wild in 1836 was hotly contested several years later by Bridge Jagon, who claimed to be his widow, and John and Mary Harper, who claimed to have been left the land in Wild's will. A ruling was made in favour of Mary Harper and it came into her possession at the beginning of 1851. The John Harper mortgaged the property to John Thomas Neale in December 1864, but about three years later it was sold to Jacob Christian Fischer, probably as a means of settling the payment of the mortgage. After Jacob Fischer died in August 1894 titled passed to his widow Jane, and on her death in December 1905 to her son George. On 1 July 1908 it was then conveyed from George Fischer to Sir Matthew Harris. Harris (1841-1917) was the great nephew of John Harris of Ultimo. He acquired a large amount of real estate, partly through inheritance, and between 1881 and 1900 he represented the Ward of Denison on the Sydney Municipal Council, and Sydney-Denison in the Legislative Assembly between 1894 and 1901. Harris served as Mayor of Sydney between 1898 and 1900. He later became president of Sydney Hospital was a vice president of the Royal Agricultural Society and president of the Wentworth Park Trust. In all probability Harris purchased the property as an investment.[1]

The property remained in the possession of the Harris family until 1927, when it was then sold to Sun Newspapers Limited.[1]

Early development on the site

editBy 1835 the land granted to Francis Wild and William Roberts was substantially developed but Josephson's more substantial adjoining lot was relatively empty, containing only four detached, domestically scaled buildings along Phillip Street. However, by the second half of the 1830s the section of Elizabeth Street between Hunter and King streets was "bounded on both sides ... by a series of irregular-built private dwellings - some of them having, however, a respectable appearance; but the principal buildings are towards the south end of the section, near which, a very handsome enclosed series of Chambers, for the use of the legal profession, have been erected; communicating with Elizabeth and Phillip Street, and being in the immediate vicinity of the Supreme Court House, they are found to be very convenient by the gentlemen of the law ..." Already the legal profession was congregating in this part of Sydney. Phillip Street, by contrast, was relatively undeveloped.[1]

By 1842 Wentworth Chambers, the future site of 60-70 Elizabeth Street and possibly the "handsome enclosed series of Chambers" previously mentioned, had been erected on part of Josephson's grant. At the end of the 1840s the character of Elizabeth Street had undergone substantial change. The section between Hunter and King streets showed that "with few exceptions the whole of the buildings are of modern construction, and being situated in the vicinity of the Supreme Court, are principally occupied as Chambers by the Barristers, and other members of the Legal Profession". Wentworth Chambers consisted of two single storeyed gabled buildings with an open passage running between them. Josephson appears to have lived or operated chambers on the opposite side of the street at the same period.[1]

Joseph Josephson's land was brought under the provisions of the Real Property Act in February 1863 by his son. It was one of the earliest properties in NSW to have been brought under these provisions, and at the time much of it was occupied by a number of houses that fronted Elizabeth and Phillip Street. A Certificate of Title dated 30 September 1873 confirms that Joshua Josephson was the owner of the land. Wentworth Court, or Place as it was termed, was occupied by "weekly tenants" in the middle of the 1870s. By the first half of the 1880s the building was known as Wentworth Court and contained a ground floor and two upper levels. It was considered to be sufficiently important in the middle of this decade to warrant separate listing in Sands Sydney and suburban directory. Its mixed tenants included artists, merchants, watchmakers, surveyors, and most of all, solicitors and barristers. A photograph of the building taken in May 1926, shortly before it was demolished, shows its Elizabeth Street facade to have been a restrained three storey building with a high parapet and a simple tripartite fenestration pattern. At the same time, the Phillip Street facade was more elaborate in its decorative treatment and punctuated by arched openings, in addition to being a storey taller.[1]

The title of the land was transferred to Sydney Arthur Josephson and William Edward Wilson as joint tenants. Title to the land was transferred from Josephson and Wilson to Sun Newspapers Ltd in stages, from May 1920 to February 1921. The site was then consolidated when Sun Newspapers Ltd purchased a large amount of Lot 18 from the Harris Family during 1927. It has not been ascertain when the company purchased Lot 8 or part thereof.[1]

Sun Newspapers

editThe Australian Newspaper Company was one of several that published newspapers in Sydney during the 1890s. Its Australian Star was one of only two afternoon tabloid newspapers published in Sydney during that decade. However, after 1901 the company began to run at a loss. In 1907 it started attempts to raise capital, and towards the end of 1908 it needed to raise capital to fund new plant and for other purposes. The chairman of the Company, Sir Robert Anderson, approached the managing director of the Associated Tobacco Companies, Sir Hugh Denison, for a loan to assist these funding requirements. Despite obtaining the loan, in a relatively short period of time the Australian Newspaper Company found itself contemplating the very real prospect of liquidation. One of its directors, Herbert Easton, induced Sir Hugh Denison to examine the company's position, and the result was that a consortium of a number of Sydney's businessmen formed a new company that was called the Sun Newspaper Company Limited. Two of the board of the Australian Newspaper Company served on the board of the new organisation, and a complete overhaul of its publications was made. The Australian Star remained in publication for a further three months, whilst the Sunday Sun was transformed into a daily paper, and the first issue of its successor, The Sun, was issued on 1 July 1910. Its editor, Montague Grover, aimed to provide the publication with something new:[1]

...[h]e succeeded so well that many of his differences have since become the routine of up-to-date journalism. Prior to the advent of The Sun, Australian newspapers did not have front windows for the display of their best goods, but now most of them have followed the fashion of printing their leading news items on the front page. Sedater [sic] schools of journalism looked askance at many of Mr. Grover's "revolutionary" changes, but the public evinced a growing appetite for them. Crispness and brightness of presentation in all department of news was the aim.[1]

Circulation on the first day was double that of The Star, helped no doubt by promotional stunts such as motor boats bearing Sun posters speeding around the harbour and a chariot drawn by seven horses driven by a golden haired "Apollo" traversing Sydney's streets. The new newspaper turned out to be no less surprising, with news on the front page instead of the expected advertising and changes to the conventional layout of newspapers from that era. The sun was successful because, amongst other things, its publishers made great and innovative use of a cable service from overseas and gave a large amount of its space over to crime and human interest stories. Further increases in circulation meant that the premises occupied by the newspaper became inadequate, so land at the rear of the Castlereagh Street building, extending back to Elizabeth Street, was purchased and a new building was erected over the entire site. The building was completed towards the end of 1915.[1]

In 1918 Sun Newspapers Ltd took over the failing The Northern Times in Newcastle and changed its name to The Newcastle Sun, and erected a new four storey building in Hunter Street, Newcastle. This was designed by architect Joseph Kethel. During the second half of the 1920s the company expanded its interests still further. The Daily Telegraph Newspaper Co Ltd, which had been founded in 1879 and had erected a very large building at the corner of King and Castlereagh Streets between 1912 and 1916, found itself falling behind in this competitive era. A new company was set up to incorporate the Daily Telegraph Newspaper Co Ltd, with holding the controlling interests in it.[1]

In January 1921 Moore Street, which extended between Pitt and Castlereagh Streets beyond Martin Place, which only stretched between George and Pitt Streets, was renamed Martin Place as well. Evidently Sun Newspapers Ltd recognised that the extension would eventually take place, reflected by the purchase of the property between Elizabeth and Phillip Streets from Josephson and Wilson that concluded in February 1921. The building occupied by Sun Newspapers Ltd was located at the head of Martin Place and so right in the path of the proposed extension of the street through from Castlereagh Street to Macquarie Street. This had been suggested as far back as 1909 by a Royal Commission into the improvement of the City of Sydney.[1]

Architect Joseph Kethel lodged an application for a new building with the Sydney City Council on 18 January 1926, and the following May another application was lodged, this one for the demolition of Wentworth Court. However, two months later an application was ledged, this one for the demolition of Wentworth Court. However, two months later an application was lodged by the building contractors Stuart Bros for the excavation of the site and yet another application was lodged for demolition a few days after that.[1]

In the meantime, however, Sun Newspapers Ltd organised an architectural competition that was held in 1926, with six architects selected to submit entries, indicating that the newspaper was reconsidering its new premises. The entries were adjudicated by Professor Leslie Wilkinson, Chair of the School of Architecture at the University of Sydney, and Kingsley Henderson, a prominent architect from Melbourne whose practice designed many major office buildings throughout Australia during the 1920s and into the 1930s. "After adjudication had been carried out in the usual way, and the names of the competitors kept sealed until after the award had been made, by a remarkable coincidence the winner, Mr J Kethel, turned out to be the architect who had carried out the "Sun" Newspapers' work for many years past..." Kethel lodged a revised application for the new building on 27 July 1927. The structural engineer for the project was E. Leslie James.[1]

Joseph Alexander Kethel

editJoseph Alexander Kethel was born on 31 January 1866. He was the second son of Alexander Kethel and was indentured into the practice of Thomas Rowe and Sydney Moore Green, architects, in 1887. A number of business premises located in Sydney were designed in Kethel's office. They included the building for Alliance Assurance Company at 97 Pitt Street (demolished), the London Assurance Building at 16-20 Bridge Street (demolished), major alterations to an office building at 16 Loftus Street, Sydney (c. 1921, demolished) and numerous private residences and pastoral homesteads. The buildings included "Cavan" in the vicinity of Yass, "Chatsworth" at Potts Point (1922, demolished) and a residence at Leura, both for William Rhodes (demolished), ecclesiastical buildings such as the former Fuller Memorial Church in Surry Hills and theatres such as the Independent Theatre at North Sydney. Kethel held the position of Honorary Architect to the Royal Australian Historical Society. He died on 29 April 1946.[1]

Kethel was responsible for a number of earlier buildings for Sun Newspapers, so it is not surprising that he received the commission for 60-70 Elizabeth Street, for he designed the newspaper's earlier building in Castlereagh Street and its premises in Newcastle. He also designed a buildings for the publishers of Truth and Sportsman at 61-73 Kippax Street, Sydney.[1]

The Sun building

editThe newly completed Sun Building, built by Concrete Constructions, was officially opened on 15 October 1929 by the Governor of NSW, Sir Dudley de Chair. Was attended by a large number of dignitaries, including the Premier, Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, the President of the Legislative Council, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney and numerous others.[1]

The appearance of the building's exterior excited interest because it was an example of the newly popular "commercial Gothic" idiom that enjoyed a brief flowering in Sydney and other Australian cities in the second half of the 1920s and into the early 1930s. This aroused mixed feelings in some quarters. The editors of the influential architectural journal Building felt that:[1]

...[t]he five great openings at the bottom are dignified enough in themselves, only with their turned columns of Tuscan form and darker material, they do not appear to be in keeping with the rest of the ornament, which is applied to, rather than embodied in the composition. The symbol of the firm - the sun - held like a great balloon in the sky is the most daring and outstanding feature of the work. The seven floors in the shaft of the building, contained in five vertical bays, are essentially commercial and severely plain, probably intended to throw the ornamental proportions into high relief..

— Building magazine.

Some aspects of the building reflected peculiarities inherent in the height restrictions current at the time, and because of the fall across the site the building effectively ended up with two different roof levels. Towers on either side of the building served different functions. That on the Elizabeth Street side held aloft the gilded balloon representing the sun, whilst the tower on the Phillip Street side contained an observation platform. Below it, a cafeteria for the use of staff opened out onto the roof over the Elizabeth Street side of the building. Such staff amenities were relatively common parts of interwar office building design, but evidently not so common in other newspaper offices. A hospital located on the thirteenth floor was another facility provided for the benefit of the staff, as was a "mechanical suite where each departmental foreman has his own table, and mechanical toilets with enclosed showers, etc." Further consideration was shown for the staff by the use of "Vita glass" in a number of the building's windows. This proprietary glass was claimed to allow the passage of ultra violet radiation, and so benefit those working behind it.[1]

Seven high speed lifts, travelling at the maximum permitted speed of 600 feet (182 metres) per minute were installed. This was amongst the largest lift installations in any Sydney office building during the interwar period. Some of the innovations to be found in the building included the largest mechanical ventilation system installed in any Australian building of the time, (no doubt due in part to there being three floors constructed below the level of Phillip Street) while the exhaust fan in the system was the largest that had yet been installed in any Australian building up to that time. The basement levels contained the printing machinery and heavy storage.[1]

The exterior of the building was clad in a rich variety of materials. The ground floor levels were finished with Uralla granite, with emerald pearl around the windows and red granite on the Elizabeth Street facade. Above these levels it was clad in Benedict Stone of a soft grey hue. Benedict stone, apparently named after the person who invented it, appears to have been introduced in America during the 1880s. It was manufactured in a straightforward fashion - selected stone was crushed into chips and dust, then washed and mixed with a special cement. It was then poured into moulds of the required configuration. The Sun Building was the first major project in Sydney, if not Australia, to make use of this material. The decorative potential of stone was exploited to enhance parts of the interior as well. The main entrance vestibule was ornamented in "richly coloured" Cudgegong marble, whilst the main entrance stair landings and mid landings were tiled with panels depicting Apollo, the Sun God. By contract, the rest of the interiors were considered to be quite plain. The newspaper took pride in the fact that "wherever possible" Australian materials, "in keeping with the national character of the paper" were used.[1]

One very unusual feature associated with the building was the two landscaped plots in front of the Elizabeth Street facade. A central path connected the main entry and the footpath along the street. The plots, protected by chains slung between posts, were enhanced by decorative pedestals amidst expanses of lawn and young trees. Regretfully they were to have a short life, as this section of Elizabeth Street was widened around 1934.[1]

Apart from the Sun Building there were a number of large buildings erected for the publishers of newspapers in Sydney during the second and third decades of the twentieth century. They included the Daily Telegraph Building at the corner of King and Castlereagh Streets (now known as the Trust Building), designed by the architectural firm of Robertson & Marks and completed in 1916, The Sydney Morning Herald building at the corner of Hunter and O'Connell Streets, designed by the architectural firm of Manson and Pickering and completed in 1929, and the Evening News Building designed by the architectural firm of Spain and Cosh and completed in 1926.[1]

Subsequent history of Sun Newspapers Limited

editOn 1 October 1929 Sun Newspapers Ltd merged its interests with those of S. Bennett Ltd to form Associated Newspapers Limited, which was an operating as well as a holding company. The following January the new company purchased the Daily & Sunday Guardian from Smith's Newspapers Ltd and the remaining shares in Daily Telegraph Pictorial Ltd were purchased in February 1930. The directors of the company were forced to undertake some drastic measures as a result of the economic depression of the early 1930s and correspondingly reduced circulating revenue. As a result, the Evening News and Sunday Pictorial were discontinued, the Daily Guardian and Daily Pictorial were incorporated into a new newspaper called The Daily Telegraph, and the Sunday Guardian and Sunday Sun were incorporated into one newspaper. In this way the company published a morning, an evening and a Sunday newspaper. During 1936 the principal assets of S Bennett Limited were sold to Consolidated Press Holdings (of which Associated Newspapers was a shareholder), as was the goodwill of The Daily Telegraph. At this time Associated Newspapers were possessed of only one active subsidiary company in the form of Sun Newspapers Limited. It was decided to consolidate these interests and reduce operating expenses by amalgamating the two companies, and to this end Sun Newspapers was voluntarily liquidated on 29 March 1937. S. Bennett Limited was the next subsidiary to go, and was liquidated during 1938, whilst the Newcastle Sun was sold to the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate Pty Ltd. On 26 January 1938, the company launched a "pioneer journey in Pictorial News in Australia", Pix. During 1939 and 1940 the company invested in new plant and machinery to allow for expanded circulation and business, whilst at the end of 1939 a subsidiary company, Wireless Newspapers Pty Limited, was placed into voluntary liquidation. Around this time the company was also acquiring shares in Australian Newspaper Mills Pty Limited. Its stable of publications included the Daily Sun, Woman, Sunday Sun, World's News, Pix, Wireless Weekly and Radio and Hobbies. By 1943 Wireless Weekly had been replaced by Pocket Book Weekly, and despite the strictures of paper rationing circulation figures exceeded previous years.[1]

In 1947 two new magazines were introduced - Sporting Life and Glamour - and in the second half of 1949 Sungravure Limited was formed to take over the company's rotogravure printing activities. At the Annual General Meeting of Associated Newspapers held at the end of 1953, Warwick Fairfax gave notice of his candidature for election to the Board. This followed on from negotiations with John Fairfax & Sons earlier in the year that were concluded by the issue of shares to that company, to assist Associated Newspapers in improving its financial position. John Fairfax and Sons were also given representation on its Board. In June 1955, 60-70 Elizabeth Street was sold to the Government Insurance Office, or GIO,[2] at the time a controlled entity of the Government of New South Wales. Magazine and job printing rights were sold to Sungravure Limited, mirroring continued difficulties within the company. By the end of 1956 W. O. Fairfax had become Chairman of Directors whilst production and distribution of The Sun was transferred to John Fairfax & Son's Broadway premises. Employees were transferred to Sungravure and John Fairfax and Sons, which carried the bulk of newsprint requirements.[1]

In the second half of 1970 half of Sungravure Pty Limited was sold to the International Publishing Corporation, an overseas company that was the world's largest publisher of magazines. Associated Newspapers now only published The Sun and The Sun Herald. By 1974 the parent company was deriving a trading profit from the publication of The Sun and operated an interest of one-third in The Sun Herald. In a reversal of what had happened in 1970, on 21 April 1978 Associated Newspapers regained total ownership of Sungravure Pty Limited.[1]

Subsequent history of the Sun building

editEvidently Sun Newspapers Ltd foresaw the need to expand its new premises within the next decade, for its site was enlarged in October 1931 by the acquisition of a new title from the Sydney City Council of a part of the former Allotment 7, 68-70 Elizabeth Street. The Council of the City of Sydney had resumed this land the previous year, in August 1930. An application to demolish the buildings which stood on this land was made in November 1933. The site was expanded yet again by a new title in March 1936 from the addition of part of Lot 7 and part of Lot 8 in Section 40, purchased from the Council of the City of Sydney in November 1935. The Council had resumed the land in May 1935.[1]

During the second half of the 1930s architects Scott Green and Scott were responsible for the design and documentation of a series of alterations and additions to the building (refer to Appendix 3). In June 1936 Scott Green and Scott lodged an application to the building. In June 1936 Scott Green and Scott lodged an application for the enclosure of the northern lightwell in 1938, which was adjacent to the recently completed APA Building on Martin Place. Documentation describing major extensions to the building on the site of 68-70 Elizabeth Street was lodged in July 1938. This necessitated the demolition of a building called Dymocks Chambers on Elizabeth Street and Northfield Chambers (erected around 1888) at 163 Phillip Street. In June 1939 it was proposed to construct a floor across a lightwell on the fifth floor. The same architects were involved with the building continued after World War Two, but by this time was known as EA & TM Scott. They were responsible for the design and documentation associated with the construction of a mezzanine level between the sixth and seventh floors in 1946-47, a fan room on the western side of the roof of the extension and the construction of lavatory accommodation at the Phillip Street level.[1]

After ownership of the building was transferred to Associated Newspaper Ltd during the liquidation of Sun Newspapers in August 1939, from the next month part of the basement was leased by the Sydney City Council. Associated Newspapers Limited finally became proprietor of the land on 17 December 1953. The title was transferred from Associated Newspapers to the Government Insurance Office on 15 June 1955. The building was then extensively remodelled internally to suit the requirements of its new owners and many original finishes and fittings were swept away. The works were designed by the NSW Government Architect's Office and carried out by the NSW Public Works Department. At the same time extensive repairs and refitting of the steel framed windows took place, and the whole of the works were completed by the middle of 1957. Associated Newspapers tenanted a part of the building until February 1963.[1]

From 1959 onwards the building was subjected to numerous programs of alteration and modification, and for a number of years these were designed by the architectural firm of Morrow and Gordon. The modifications carried out under their direction affected a large part of the building. In 1959 the firm documented alterations to the main entrance off Phillip Street, partitions on the ninth floor and alterations to provide a car park, which included the construction of a series of ramps and "mezzanine" levels between the existing floor slabs. Between 1961 and 1964 their work included alterations to toilets and associated spaces, further alterations on the ninth floor, a covered way on the roof, a new tea room on the sixth floor, alterations on the seventh floor, and alterations to the "tank". In 1968 major upgrading of the mechanical ventilation system was documented and two years later plans were prepared for and alterations to the ground floor.[1]

Apart from Morrow and Gordon, there were other architects who were responsible for work to the building in this period. For instance, the Melbourne-based architect Guildford Bell designed facilities for Ansett Transport Industries in the basement and ground floor levels during 1959.[1]

The pace of change continued unabated during the 1970s and 1980s. Extensive alterations were carried out in 1970 and 1971, while alterations to Floors 7, 9, 10 and 11 took place in 1972. All were designed by architect R. B. Keers. In 1985 major alterations to the building, valued at $12 million, were documented by the architectural firm of Keers Banks and Maitland. This resulted in the removal of all the interior fabric excepting structural items from the ground levels upwards and installation of new services, lifts, stairs and toilet areas. New plant room accommodation was constructed at roof level, many windows were replaced and the introduction of retail tenancies on the ground floors resulted in modifications to the facades at street level. Since these extensive modifications were completed, there have been various alterations related to internal partitioning and changes in tenancies.[1][3]: 4–16

Description

editThe subject building is identified as occupying Lot 1 D.P. 87319 at 60-70 Elizabeth Street and 153-163 Phillip Street. It consists of a structural steel, reinforced concrete and masonry structure, and contains seven basement levels given over to car parking, a lower ground and ground floor level, and eleven upper floors. The building is accessed via entries on Elizabeth and Phillip Streets, whilst vehicular access is located on the southern end of the Elizabeth Street facade and the loading dock is situated on the Phillip Street side of the building.[1]

The exterior of the building was designed in what has become known as the Interwar Skyscraper Gothic style. There were relatively few buildings erected in this style in Australia, which showed the influence of American skyscraper design of the 1920s, the most notable example of which was Howells and Hood's Chicago Tribune Building of 1922-25. Indeed, this precedent was acknowledged in the Australian architectural press. The adaptation of Gothic embellishments and its inherent verticality was though appropriate as an expression of the height and vertical thrust of tall buildings in America during the 1920s. The major examples of this style of architecture in Sydney were designed and built between 1926 and 1930. The style effectively formed a bridge between the dominant Commercial Palazzo idiom of the 1920s and the Art Deco style of the late 1920s and 1930s - "... relatively few buildings were built in this style, but they provided potent images which had effects on the Art Deco style." Its characteristics, a number of which appear in the facades of 60-70 Elizabeth Street, include concentrated "medieval" motifs and detailing concentrated at the base and parapet levels of the building, vertical expression achieved by the accentuation of window mullions, and "Gothic" towers above the level of the roof to form a landmark on the city skyline.[1]

60-70 Elizabeth Street has strong visual associations with other interwar office buildings in this part of the city. They include the former APA Building to its immediate north at 53 Martin Place, the former State Savings Bank at 48-50 Martin Place and the former MLC Building at 42-46 Martin Place. As a group, the buildings provide a valuable demonstration of the ways in which architectural styles in tall office buildings evolved during the interwar period, and are evidence of the major changes that took place in this part of the city as a result of extending Martin Place to Macquarie Street.[1]

A Structure and Facade Review of the building was undertaken by Ove Arup & Partners for Rider Hunt Terotech, and is appended to this report. The building was also inspected by Roy Lumby on 8 September 1999.[1]

External fabric

editThe exterior of 60-70 Elizabeth Street has retained much of its early configuration and a relatively large amount of early fabric. The configuration of its facades is characteristic of many office buildings erected during the interwar period, consisting of a polished stone base (the ground floor cladding) that is extended into the upper part of the building by means of decorative detailing, a relatively plain shaft of window bays and decorative detailing at the top of the building and parapets. The facades were originally symmetrical and arranged in a tripartite configuration broken into five bays of windows of unequal width, but this configuration has since been obscured by the additions that were erected during the latter part of the 1930s on the southern side of the building. Early metal framed windows still remain in place in the large arched openings above the ground floor levels on both facades, although a leadlight window above the Elizabeth Street entrance, visible in early photographs, has been removed. All other windows were replaced as part of the late 1980s works. The flat roofs are covered with a proprietary membrane system, identified by Rider Hunt Terotech as "butynol". The original awning that sheltered the ground floor level of the Phillip Street facade has been removed, although the brackets that held suspension cable off the facade are still in place.[1]

Other modifications to the exterior of the building include: installation of new shop fronts on both facades; erection of canopies above the Phillip Street entrance and above shop fronts on the Elizabeth Street facade; recently installed stone cladding along the ground floor level of the Phillip Street facade, insertion of grilles above the level of ground floor openings along the Phillip Street facade and the addition of large plant room spaces on the roof levels. Many of these alterations and additions were carried out during the 1980s. However, doors to the ground floor car part vestibule in Elizabeth Street may also be remnants of early building fabric.[1]

Some parts of the building are in defective condition. Theses have been identified by Ove Arup & Partners as follows:[1]

- Concrete is spalling off the stair structure and walls in a number of locations in the tower on the eastern side of the building, and corroding reinforcement has been exposed. There is also evidence of water penetration into the tower;

- There are numerous cracks in the fire stairs, reflecting the joints between steel framing and masonry infill panels;

- Cracking has occurred in the roof parapet at the southern end of level 11 and the top of the plant room wall at the southern end of the building above level 11, on its eastern and western sides;

- The metal plant room roof has been damaged by pedestrian traffic across it, and screws fixing the roof sheeting have corroded, as have gutters associated with the roof. There has been some water penetration through the roof or from the guttering;

- Some of the hold-down bolts of the handrails around the level 10 and 11 roofs have corroded;

- There are a small number of locations where cement rendered surfaces are deteriorating and coming away;

- Two steel framed windows in the tower at level 11 are corroding;

- Staining has taken place on facade paintwork and on the reconstructed stone surfaces;

- Fittings and mechanisms on the original windows at the lower levels of the building are broken or ineffective in operation. Several of the windows do not seal properly when closed;

- Areas of dampness are evident in basement levels due to water penetration through perimeter walls, particularly in the northwestern and south western corners.

Internal fabric

editUnlike the exterior of the building, virtually all of the building's interior were removed as part of the alterations that were carried out during the 1980s. The only early fabric remaining in the building is the former board room and an adjacent anteroom of the seventh floor. There is very little else left of the original building fabric apart from structural columns, floor slabs and concrete stairs in the roof towers.[1]

The ground floor levels contain retail tenancies and a large central circulation space that links Elizabeth and Phillip Streets. Wide stairs and an escalator accommodate the change in level. Finishes throughout date from the late 1980s and are dominated by the extensive use of light toned marble. Columns are faced with mirrored glass whilst ceilings are divided into recessed sections from which large light fixtures are suspended. Floor finishes consist of carpet surrounded by a marble margin.[1]

Generally the office levels reflect fitouts undertaken by the various tenants. For instance, the foyer on the fifth floor has an "Art Deco" theme, designed by the Department of Public works around 1996. Lift lobbies are also given some distinction according to tenant requirements such as the lobby on the tenth floor, which is finished with a panelled timber dado. However, the ceilings of the lift lobbies are uniform, with coved sides and a flush ceiling decorated with plaster mouldings in a "Gothic" motif similar to that found in the ceiling of the early board room on the seventh floor.[1]

The Board Room on the seventh floor presently forms part of the Attorney General's tenancy. It and the adjacent ante room are part of the building's early fabric. Kethel's 1927 drawings do not indicate a board room at this level nor does it appear in Scott, Green & Scott's 1938 documentation. It is quite possible that it was decided to locate the two rooms here whilst the building was under construction, or they may have been relocated from another level during the works carried out during the 1980s. Original fabric in these spaces includes timber wall panelling, timber parquet floor and a fireplace with a low panelled timber ceiling above it in the board room. The ceiling above the rest of the Board Room may also be original. The ante room has only retained early timber wall panelling, although earlier ceilings may be concealed above the existing suspended ceiling, and original flooring may be concealed beneath present coverings. Wall mounted light fixtures and other luminaires are recent fabric.[1]

The toilet areas throughout the building are fitted out with recently installed fabric, as are the lift cars. There are now five lifts, two fewer than when the building was first completed. The lift cars are lined in timber, with panelled timber ceilings.[1][3]: 52–55

The building was constructed in 1929 to house the offices and printing presses of The Sun newspaper, an afternoon tabloid, which ran from 1910 until the 1980s. Sun Newspapers Limited occupied this site from 1929 until 1939. Joseph Kethel won the architectural competition top design the building. After the liquidation of Sun Newspapers in August 1939, the building was owned by Associated Newspapers Ltd. This building was the last of the great newspaper buildings to be built in the Sydney central business district, and the spectacular Skyscraper Gothic style confidently portrayed the commercial power of the media. The former Sun Building is one of only three in the city to be designed in this architectural style; with the other two being the Grace Hotel and the State Theatre.[4]

Heritage listing

editAs at 27 August 2008, The GIO Building is historically significant because of its associations with Sun Newspapers Ltd newspaper publishing activities in Sydney during the first half of the twentieth century. Its site has associations with the historically prominent figure, Joshua Josephson.[1]

The building is aesthetically significant because it is possibly the first major Interwar Skyscraper Gothic style building in Sydney, of which it is also a rare example, and because it is a major building designed by architect Joseph Kethel.[1]

The building has technical significance, due to its early and extensive use of the proprietary building material, Benedict stone. It is possibly the first major application of this material in a large city building in NSW.[1][3]: 71

GIO Building was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

60-70 Elizabeth Street has important associations with Sun Newspapers Ltd, which did much to change the way in which newspapers were published in Sydney in the early part of the twentieth century, and with the subsequent publication of newspapers up until the mid twentieth century.[1]

It is one of a number of large buildings erected specifically for the use of newspaper publishing in the second and third decades of the twentieth century in the City of Sydney. However, evidence of this past use has been removed from much of the building's interior.[1]

The site has historical associations with the significant figure of Joshua Josephson, who was a prominent legal figure and for a time mayor of Sydney, as well as holding property interests in the city centre.[1][3]: 70

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

60-70 Elizabeth Street is an important work by the architect Joseph Kethel, who was responsible for the design of a number of buildings for newspaper publishers during the first third of the twentieth century and designed a wide range of other buildings.[1]

The building is a rare example of a large Interwar Skyscraper Gothic style building in the City of Sydney, with a relatively intact exterior. It was the first major example of this style to be erected in Sydney, and may be the first to have been erected in Australia. The building also contains a small amount of original internal fabric in the form of the boardroom on the seventh floor and the associated ante room.[1]

The building is an important part of the architectural fabric of the area around Martin Place, Elizabeth Street and Phillip Street and has strong visual relationship with the former APA Building and other major interwar office buildings in this locality.[1][3]: 70

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The building is not considered to demonstrate any social significance. It does not appear to have any association with a contemporary community for social, spiritual or other reasons.[1][3]: 70

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The exterior of the building has technical significance because it was the first time that a proprietary synthetic stone, Benedict stone, was employed as the cladding of a major building in Sydney.[1][3]: 70

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi "GIO Building". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00683. Retrieved 13 October 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ Berry, Vanessa (17 November 2015). "A City Sun". Mirror Sydney. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rod Howard Heritage Conservation Pty Ltd (2001). 60-70 Elizabeth Street (GIO Building).

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Former Sun Building". Sydney Architecture. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

Bibliography

edit- Rod Howard Heritage Conservation Pty Ltd (2001). Conservation Management Plan - 60-70 Elizabeth Street (GIO Building).

Attribution

editThis Wikipedia article contains material from GIO Building, entry number 683 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links

edit- "Former GIO Building". Elizabeth Street Heritage Walk. Australia For Everyone. 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Former "Gio" Building Including Interiors". New South Wales Heritage Database. Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 13 December 2018.