Gaius Duilius (fl. 260–231 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. As consul in 260 BC, during the First Punic War, he won Rome's first ever victory at sea by defeating the Carthaginians at the Battle of Mylae. He later served as censor in 258, and was appointed dictator to hold elections in 231, but never held another command.

Gaius Duilius | |

|---|---|

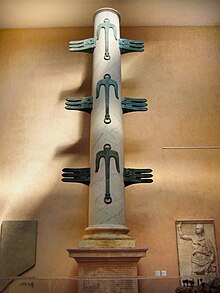

Reproduction of the victory column of Gaius Duilius | |

| Dictator of Rome | |

| In office 231 BC | |

| Censor of Rome | |

| In office 258 BC | |

| Consul of Rome | |

| In office 260 BC | |

| Personal details | |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Awards | Triumph |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Rome |

| Branch/service | Roman navy |

| Battles/wars | |

Background

editGaius Duilius, whose father and grandfather were both named Marcus Duilius,[1] belonged to an undistinguished family. One Caeso Duilius is recorded as consul in 336 BC, but the surname is otherwise only known historically and reliably from a few minor magistrates in the fourth century BC.[2]

Career

editNaval victory

editDuilius was one of the consuls for the year 260 BC, and was initially appointed to command Rome's land forces in Sicily against Carthage, as part of the First Punic War. His colleague in office, Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio, held charge of the fleet.[3][note 1] The Romans built 120 warships and despatched them to Sicily in 260 BC for their crews to carry out basic training. Scipio sailed with the first 17 ships to arrive to the Lipari Islands, a little way off the north-east coast of Sicily, in an attempt to seize the islands' main port, Lipara. The Carthaginian fleet was commanded by Hannibal Gisco and was based at Panormus, some 100 kilometres (62 miles) from Lipara. When Hannibal heard of the Romans' move he despatched 20 ships. When these attacked, Scipio's inexperienced men offered little resistance and the consul himself was taken prisoner. All of the Roman ships were captured, most with little damage.[5][6] This forced Duilius to hand over the legions to the tribunes and assume control of the Roman fleet himself.[7] A little later, Hannibal was scouting with 50 Carthaginian ships when he encountered the full Roman fleet. He escaped, but lost most of his ships.[8]

Manoeuvring galleys at sea required long and arduous training.[9] As a result, the Romans were at a disadvantage against the more experienced Carthaginians. To counter this, the Romans introduced the corvus, a bridge 1.2 metres (4 feet) wide and 11 metres (36 feet) long, with a heavy spike on the underside of the free end, which was designed to pierce and anchor into an enemy ship's deck.[10] This allowed Roman legionaries acting as marines to board enemy ships and capture them, rather than employing the previously traditional tactic of ramming.[11]

Duilius, hearing that a Carthaginian squadron under Hannibal Gisco was attacking Mylae, promptly sailed, seeking battle. The two fleets met off the coast of Mylae in the Battle of Mylae. Hannibal had 130 ships, and the historian John Lazenby calculates that Duilius had approximately the same number.[12] The Carthaginians anticipated victory, due to the superior experience of their crews, and their faster and more manoeuvrable galleys, and broke formation to close rapidly with the Romans.[13] The first 30 Carthaginian ships were grappled by the corvus and successfully boarded by the Romans, including Hannibal's ship – he escaped in a skiff. Seeing this, the remaining Carthaginians swung wide, attempting to take the Romans in the sides or rear. The Romans successfully countered and captured a further 20 Carthaginian vessels.[note 2] The surviving Carthaginians broke off the action, and being faster than the Romans were able to escape. This clash was Rome's first ever naval victory. Duilius sailed to relieve the Roman-held city of Segesta, which had been under siege.[13][15]

Further successes

editFollowing his victory at sea, Duilius resumed his command of the legions in Sicily.[note 3] Landing probably at the gulf of Termini, he relieved Segesta of its siege by the Carthaginian Hamilcar, and then stormed the fortress of Macella (possibly Macellaro near Camporeale).[18][19][20] As his term as consul neared its end, Duilius returned to Rome to hold elections and to celebrate, in early 259, the first Roman triumph for a naval victory. With part of the spoils, Duilius built a temple to Janus at the Forum Holitorium, and a column adorned with the ramming beaks (rostra) of captured warships was erected in the Forum to celebrate his victory.[18][19] He was also accorded the special honour of being accompanied by a torchbearer and flute-player while returning home from dinner at night.[21][22]

Duilius went on to hold the office of censor in 258–257, and was later, in 231, appointed dictator to hold elections. He was said to have lived to old age, and Cato the Censor may have claimed to have seen the aged Duilius during his own childhood.[22] Despite this, Duilius never held another military command, though he may have participated in a raid on Africa in 247. Lazenby suggested that, since he lacked an aristocratic pedigree, the nobility "may have got tired of his boastfulness", if the tone of the commemorative inscription attached to his column (CIL VI, 1300) reflects his own attitude.[21]

Legacy

editIn the Twentieth Century, the Italian Navy named several warships after Duilius, including the battleship Duilio.

Due to Duilius' victory being commemorated with a column adorned with the ramming beaks (rostra) of captured warships being erected in the Forum, behind where speakers were standing when delivering a speech, the word "Rostrum" gained in Latin - and thence to various modern languages - the meaning of referring to a dais.

Notes, citations and sources

editNotes

edit- ^ A commemorative inscription claims Duilius oversaw the construction of the fleet, although the consuls may have seen to it jointly.[4]

- ^ The figures for Carthaginian losses are taken from Polybius. Other ancient sources give 30 or 31 ships captured and 13 or 14 sunk.[14]

- ^ Literary sources place Duilius's operations on land after the victory at sea, but commemorative inscriptions mention the former first. The literary evidence is usually preferred, and inscriptions may not, in any case, have recorded events in chronological order. .[16][17]

Citations

edit- ^ Münzer 1905, col. 1777.

- ^ Kondratieff, p. 1.

- ^ Caven, p. 28

- ^ Walbank 1990, p. 76.

- ^ Harris 1979, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 181.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 70.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 67.

- ^ Casson 1995, pp. 278–280.

- ^ Casson 1995, p. 121.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Bagnall 1999, p. 63.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 16.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Walbank 1990, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b Caven, p. 30.

- ^ a b Münzer 1905, col. 1780.

- ^ Walbank 1990, p. 80.

- ^ a b Lazenby 1996, p. 72.

- ^ a b Münzer 1905, col. 1781.

Sources

edit- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Casson, Lionel (1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5130-8.

- Caven, Brian (1980). The Punic Wars. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77633-9.

- Harris, William (1979). War and Imperialism in Republican Rome, 327–70 BC. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814866-1.

- Kondratieff, Eric (2004). "The Column and Coinage of C. Duilius: Innovations in Iconography in Large and Small Media in the Middle Republic". Scripta Classica Israelica. 23: 1–39.

- Lazenby, John (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Münzer, Friedrich (1905). "Duilius 3". Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Vol. 5, part 2.

- Walbank, F.W. (1990). Polybius. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06981-7.