Garganornis (meaning "Gargano bird") is an extinct genus of enormous flightless anatid waterfowl from the Late Miocene of Gargano, Italy. The genus contains one species, G. ballmanni, named by Meijer in 2014. Its enormous size is thought to have been an adaptation to living in exposed, open areas with no terrestrial predators, and as a deterrent to the indigenous aerial predators like the eagle Garganoaetus and the giant barn owl Tyto gigantea.

| Garganornis Temporal range: Late Miocene,

| |

|---|---|

| |

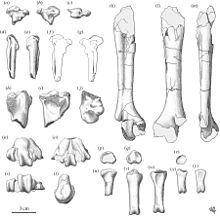

| Drawings of Garganornis material discovered from Gargano and Scontrone localities | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | †Garganornis Meijer, 2014 |

| Species: | †G. ballmanni

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Garganornis ballmanni Meijer, 2014

| |

Description

editThe tibiotarsus of Garganornis is approximately 30% larger than that of the living mute swan in circumference. Based on comparisons with the latter, it has been estimated that Garganornis had a weight in the range of 15–22 kilograms (33–49 lb), larger than any living anatid. This suggests that it was likely flightless.[1]

The preserved carpometacarpi from the wings had quite a short and robust shaft, much shorter than any of the living large-bodied anseriforms that are capable of flight. The carpometacarpus was also peculiarly flattened on its top end; and the trochlea carpalis (a bony articular process that drives wing extension and flexion) is reduced and weak in shape, limiting wrist movement - both likely adaptations to a flightless life.[2]

In some specimens of Garganornis, there is a small bony knob on the top of the carpometacarpus that is similar to that of swans, geese, ducks, and other anseriforms; this was likely used for fighting, as in other members of the group.[2][3]

Likewise short and robust was the tarsometatarsus of the foot. The processes known as the trochlea metatarsi II and IV, on the bottom portion of the tarsometatarsus, are more equal in length than most other anseriforms, with the exception of the Cape Barren goose, screamers, and the giant, extinct Cygnus falconeri. The phalanx bones of the toes are also relatively robust, and similar to other giant anseriforms; however, the impressions of ligaments on the bones are weaker and less defined.[2]

Discovery and naming

editThe first remains of Garganornis were discovered from the Posticchia 5 fissure filling near the town of Apricena in Gargano, Italy. These deposits are part of the Miocene Mikrotia faunal assemblage (named after an abundant murid rodent), which has been dated to 6–5.5 Ma in age. The holotype consists of a single partial left tibiotarsus, catalogued as RGM 443307, which was described by Meijer in 2014.[1]

Additional material was later described from Gargano by Pavia et al. in 2016, consisting of partial carpometacarpi (DSTF-GA 49, NMA 504/1801), a single damaged tibiotarsus (DSTF-GA 77), partial tarsometatarsi (RGM 425554, RGM 425943), and various phalanx bones from the foot (MGPT-PU 135356, RGM 261535, RGM 261945). Additionally, some geologically earlier but morphologically comparable material was described from the Scontrone locality, which is close to the town of Scontrone and has been dated to 9 Ma in age. This material consists of an almost complete tarsometatarsus, SCT 23; although it is temporally separated from the other material, the morphology and unusually large size of the bone suggests that it pertains to Garganornis.[2]

The genus name Garganornis is derived from the general area of Gargano, in which the holotype fossils were discovered; the Greek suffix ornis means "bird". The species name honors Peter Ballmann, who first described the birds of the Gargano region.[1]

Classification

editSeveral characteristics of the tibiotarsus allow Garganornis to be placed definitely in the order Anseriformes: the medial condyle is angled medially and bears a projection at its front end; and the canal of the extensor tendon is placed centrally over the intercondylar fossa.[1] Features of the carpometacarpus allow for a more specific assignment to the family Anatidae: the extensor process is parallel to the trochlea carpalis and is not tilted towards the bottom; the pisiform process is wide and unpointed; and a small knob is present above the caudal carpal fovea.[2]

Garganornis peculiarly shares a number of characteristics in the tibiotarsus with another group of large anseriforms, the Gastornithidae.[4] In particular, the intercondylar fossa is wide, the bottom opening of the extensor canal is circular (although it is placed more centrally relative to the condyles than in gastornithids), the extensor sulcus is relatively deep, and the pons supratendineus (a projection above the opening of the extensor canal) has a depression on its side.[1] However, given that gastornithids and other Paleogene fauna do not appear to have survived in - or even reached - this region, it is more likely that these shared traits are convergent adaptations to gigantic body sizes.[2]

Paleoecology

editSurveys conducted by P. Ballmann in the 1970s revealed a diverse bird fauna in the Gargano locality, consisting of 16 different taxa;[5] later work established the presence of 10 additional distinct taxa (not including Garganornis), bringing the total to 26.[6] These include the anatids Anas cf. velox and an additional unnamed anatid;[7] the giant eagles Garganoaetus freudenthali and G. murivorus,[5] as well as an unnamed smaller accipitrid;[6] the phasianid Palaeortyx volans;[8] the owls Tyto robusta, T. gigantea, "Strix" perpasta,[5] another species referred to Strix, an additional species referred to Athene, and an unnamed taxon formerly referred to T. sanctialbani;[6] the pigeon Columba omnisanctorum; the swift Apus wetmorei;[5] the sandpipers Calidris sp. and an unnamed taxon;[7] a threskiornithid; a woodpecker; a songbird; two rails; two charadriiforms; a bustard; a mousebird; and a corvid.[6] To date, Garganornis is the only bird that is found in both the Gargano and Scontrone localities; the lack of other Gargano birds in Scontrone is probably a result of taphonomic bias.[2]

Asides from birds, various mammals and reptiles are known from the Gargano and Scontrone localities. Most notably, the giant murid Mikrotia (including M. magna, M. parva, and M. maiuscula) is very abundant; the genus lends its name to the entire local ecosystem, which has become known as the Mikrotia fauna.[9][10] A second murid, Apodemus sp., is also present. Other rodents include the giant dormice Stertomys laticrestatus, S. daunius, and S. lyrifer, along with the smaller species S. deguili, S. simplex, and S. daamsi;[11][10][12] and the hamsters Hattomys gargantua, H. nazarii,[11][10][12] Neocricetodon sp., and Apocricetus sp.[11] The gymnures (hairy hedgehogs) Deinogalerix freudenthalli, D. minor, D. intermedius, D. brevirostris, D. koenigswaldi, and D. masinii were also giant,[11][12] while their smaller relative Apulogalerix cf. pusillus is also present.[10] Other mammals include the crocidosoricine shrew Lartetium cf. dehmi;[10] the pikas Prolagus apricenicus and P. imperialis;[11] the deer-like hoplitomerycid Hoplitomeryx mathei; and the otter Paralutra garganensis.[12] There is one reptile genus: a crocodile referred to Crocodylus.[13]

Garganornis and the rest of the Mikrotia fauna has been dated to the Tortonian stage of the Late Miocene.[12] During the Miocene, the Gargano and Scontrone areas were part of an isolated archipelago that has been referred to as the Apulia-Abruzzi Palaeobioprovince.[14] Small mammals, including the gymnure ancestors of Deinogalerix, probably reached these islands via rafting.[12]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Meijer, H.J.M. (2014). "A peculiar anseriform (Aves: Anseriformes) from the Miocene of Gargano (Italy)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 13 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2013.08.001.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pavia, M.; Meijer, H.J.M.; Rossi, M.A.; Göhlich, U.B. (2017). "The extreme insular adaptation of Garganornis ballmanni Meijer, 2014: a giant Anseriformes of the Neogene of the Mediterranean Basin". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (1): 160722. Bibcode:2017RSOS....460722P. doi:10.1098/rsos.160722. PMC 5319340. PMID 28280574.

- ^ Hume, J.P.; Steel, L. (2013). "Fight club: a unique weapon in the wing of the solitaire, Pezophaps solitaria (Aves: Columbidae), an extinct flightless bird from Rodrigues, Mascarene Islands". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 110 (1): 32–44. doi:10.1111/bij.12087.

- ^ Buffetaut, E. (2008). "First evidence of the giant bird Gastornis from southern Europe: a tibiotarsus from the Lower Eocene of Saint-Papoul (Aude, southern France)" (PDF). Oryctos. 7: 75–82.

- ^ a b c d Ballmann, P. (1976). "Fossile Vögel aus dem Neogen der Halbinsel Gargano (Italien), zweiter Teil" [Fossil Birds from the Neogene of Gargano Peninsula (Italy), part two]. Scripta Geologica. 38: 1–59.

- ^ a b c d Pavia, M. Fossil birds from the Neogene of the Gargano (Apulia, SE Italy). Neogene Park: Vertebrate Migration in the Mediterranean & Paratethys. Scontrone: RCMNS Interim Colloquium. pp. 78–80.

- ^ a b Pavia, M. (2013). "The Anatidae and Scolopacidae (Aves: Anseriformes, Charadriiformes) from the late Neogene of Gargano, Italy". Geobios. 46 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2012.10.013.

- ^ Göhlich, U.B.; Pavia, M. (2008). "A new species of Palaeortyx (Aves: Galliformes: Phasianidae) from the Neogene of Gargano, Italy" (PDF). Oryctos. 7: 95–108.

- ^ Freudenthal, M. (1973). "Rodent stratigraphy of some Miocene fissure fillings in Gargano (prov. Foggia, Italy)". Scripta Geologica. 37: 1–23.

- ^ a b c d e Masini, F.; Rinaldi, P.M.; Savorelli, A.; Pavia, M. (2013). "A new small mammal assemblage from the M013 Terre Rosse fissure filling (Gargano, South-Eastern Italy)". Geobios. 46 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2012.10.003.

- ^ a b c d e Masini, F.; Rinaldi, P.M.; Petruso, D.; Surdi, G. (2010). "The Gargano Terre Rosse faunas: an overview". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologica e Stratigrafia. 116 (3): 421–435.

- ^ a b c d e f Freudenthal, M.; van den Hoek Ostende, L.W.; Martín-Suárez, E. (2013). "When and how did the Mikrotia fauna reach Gargano (Apulia, Italy)?". Geobios. 46 (1): 105–109. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2012.10.004.

- ^ Delfino, M.; Rossi, M.A. (2013). "Fossil crocodylid remains from Scontrone (Tortonian, Southern Italy) and the late Neogene Mediterranean biogeography of crocodylians". Geobios. 46 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2012.10.006. hdl:2318/130008.

- ^ Masini, F.; Petruso, D.; Bonfiglio, L.; Mangano, G. (2008). "Origination and extinction patterns of mammals in three central Western Mediterranean islands from the Late Miocene to Quaternary" (PDF). Quaternary International. 182 (1): 63–79. Bibcode:2008QuInt.182...63M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.09.020. hdl:10447/36974.