Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch: Gerrit van Honthorst; 4 November 1592 – 27 April 1656)[1] was a Dutch Golden Age painter who became known for his depiction of artificially lit scenes, eventually receiving the nickname Gherardo delle Notti ("Gerard of the Nights").[1] Early in his career he visited Rome, where he had great success painting in a style influenced by Caravaggio. Following his return to the Netherlands he became a leading portrait painter. Van Honthorst's contemporaries included Utrecht painters Hendrick Ter Brugghen and Dirck van Baburen.[2]

Gerard van Honthorst | |

|---|---|

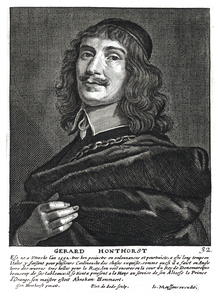

Portrait in Het Gulden Cabinet, 1662 | |

| Born | 4 November 1592 |

| Died | 27 April 1656 (aged 63) Utrecht, Dutch Republic |

| Education | Abraham Bloemaert |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | The Matchmaker |

| Movement | Utrecht Caravaggism Classicism |

| Patron(s) | Vincenzo Giustiniani |

Early life

editVan Honthorst was born in Utrecht, the son of a decorative painter, and trained under his father, and then under Abraham Bloemaert.[3]

Italy

editHaving completed his education, Honthorst went to Italy, where he is first recorded in 1616.[3] He was one of the artists from Utrecht who went to Rome at around this time, all of whom were to be deeply influenced by the recent art they encountered there. They were named the Utrecht caravaggisti. The other three were Dirk van Baburen, Hendrick ter Bruggen and Jan van Bijlert.[4] In Rome he lodged at the palace of Vincenzo Giustiniani, where he painted Christ Before the High Priest, now in London's National Gallery.[3] Giustiniani had an important art collection, and Honthorst was especially influenced by the contemporary artists, including Caravaggio, Bartolomeo Manfredi and the Carracci. He was particularly known for his depiction of artificially lit scenes.[1] Cardinal Scipione Borghese became another important patron, securing important commissions for him at San Silvestro Della Mariro, Montecompatri, and at Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. He also worked for Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.[1]

Return to Utrecht

editHonthorst returned to Utrecht in 1620, and went on to build a considerable reputation both in the Dutch Republic and abroad.[3] In 1623, the year of his marriage, he was president of the Guild of St. Luke in Utrecht. He soon became so fashionable that Sir Dudley Carleton, then English envoy at The Hague, recommended his works to the Earl of Arundel and Lord Dorchester. In 1626 Honthorst hosted a dinner for Rubens, and painted him as the honest man sought for and found by Diogenes.[5]

Royal patronage

editQueen Elizabeth of Bohemia, sister of Charles I of England and Electress Palatine, then in exile in the Netherlands, commissioned Honthorst as a painter and employed him as a drawing-master for her children.[when?] Through her he became known to Charles, who invited him to England in 1628. There he painted several portraits, and a vast allegory, now at Hampton Court, of Charles and his queen as Diana and Apollo in the clouds receiving the Duke of Buckingham as Mercury and guardian of the King of Bohemia's children. He painted a more intimate group portrait of The Four Eldest Children of the King of Bohemia, (also at Hampton Court) in which the two eldest are depicted as Diana and Apollo.[5]

After his return to Utrecht, Honthorst retained the patronage of the English monarch, painting for him, in 1631, a large picture of the king and queen of Bohemia and all their children.[5] At around the same time he painted some pictures illustrating the Odyssey for Lord Dorchester, and some showing incidents of Danish history for Christian IV of Denmark. He also painted a portrait of the king's daughter Countess Leonora while she was in the Hague.

His popularity in the Netherlands was such that he opened a second studio in the Hague, where he painted portraits of members of the court, and taught drawing.[3] These large studios, where the work included making replicas of Honthorst's royal portraits, employed a large number of pupils and assistants;[3] according to one pupil, Joachim von Sandrart, describing his experiences in the mid-1620s, Honthorst would have about 24 students at any one time, each paying 100 guilders a year for their education.[6]

His brother Willem van Honthorst (1594–1666) was also a portrait painter. Many of Willem's paintings were previously misattributed to Gerrit due to the similarity of their signatures. Willem was a pupil of Abraham Bloemaert, and was also taught by his own elder brother. In 1646 he went to Berlin, where he became court painter to Louise-Henriette, wife of the elector Frederick II of Brandenburg. He returned to Utrecht in 1664.[7]

Nickname

editHonthorst is often referred to as "Gherardo delle notti" ("Gerrit of the Nights") by modern Italians.[8] However, the nickname does not actually appear in any known Italian sources dating before Honthorst's death. Surviving Italian documents from before 1656 refer to the artist as either "Gherardo Fiammingo" ("Gerrit the Fleming") or "Gherardo Hollandese" ("Gerrit the Dutchman"), emphasizing his foreignness rather than his trademark skill at rendering nocturnal lighting. It was only in the 18th century that the nickname "Gherardo delle notti" came into widespread use.[9]

Legacy

editHonthorst was a prolific artist. His most attractive pieces are those in which he cultivates the style of Caravaggio, often tavern scenes with musicians, gamblers and people eating. He had great skill at chiaroscuro, often painting scenes illuminated by a single candle.[5]

Some of his pieces were portraits of the Duke of Buckingham and his family (Hampton Court), the King and Queen of Bohemia (Hanover and Combe Abbey), Marie de Medici (Amsterdam Stadthuis), 1628, the Stadtholders and their Wives (Amsterdam and The Hague), Charles Louis and Rupert, Charles I's nephews (Musée du Louvre, St Petersburg, Combe Abbey and Willin), and Baron Craven (National Portrait Gallery, London). His early style can be seen in the Lute-player (1614) in the Louvre, the Martyrdom of St John in Santa Maria della Scala at Rome, or the Liberation of Peter in the Berlin Museum.[5]

His 1620 The Adoration of the Shepherds in the Uffizi was destroyed in the Via dei Georgofili Massacre of 1993.[10]

Honthorst's 1623 The Concert was purchased for an undisclosed sum by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., from a private collection in France in November 2013. The painting had not been on view since 1795. The 1.23-by-2.06-metre (4.0 by 6.8 ft) The Concert went on display for the first time in 218 years in a special installation at the National Gallery of Art's West Building on 23 November 2013. It remained there for six months before going on permanent display in the museum's Dutch and Flemish galleries.[11]

Gallery

edit- Gerard van Honthorst's religious paintings

-

St. Peter Being Freed from Prison, 1616–1618, Berlin State Museums

-

Adoration of the Child, 1620

-

Christ before the High Priest, c. 1617, National Gallery, London

-

Mocking of Christ by Gerard van Honthorst

-

The Denial of Saint Peter, c. 1620

- Gerard van Honthorst's paintings of musicians

-

King David Playing the Harp

-

The Happy Fiddler, 1623 Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

-

Lute Player, 1624

-

The Happy Violinist with a Glass of Wine, 1624, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

-

Woman with guitar 1631, Lviv National Art Gallery

-

Woman Playing the Guitar

-

Man with viola da gamba

-

Merry Company

-

Merry Musician with Violin under His Left Arm

-

Supper with a Lute Player

- Other

-

Solon and Croesus

-

Portrait of William II (1626–50), prins of Oranje, and Maria Stuart (1631–60)

-

The Steadfast Philosopher, 1623 Private collection

-

The soldier and the girl

-

Pendant portrait of Amalia van Solms-Braunfels

-

Margareta Maria de Roodere and Her Parents (c. 1652) Centraal Museum, Utrecht

-

Allegory of Painting (1648) Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, California

References

edit- ^ a b c d Brown, Beverley Louise, ed. (2001). "Gerrit Hermnsz. van Honthorst". The Genius of Rome 1592-1693. London: Royal Academy of Arts. p. 380.

- ^ Liedtke, Walter; Plomp, Michiel; Rüger, Axel (2001). Vermeer and the Delft School. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 58. ISBN 0870999737.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown (1997), p.62

- ^ Brown (1997), p.32

- ^ a b c d e Chisholm 1911, p. 664.

- ^ Brown (1997), p.46

- ^ "James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, 1612–1650. Royalist". National Gallery of Scotland. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Papi, Gianni (2015). Gherardo delle Notti : Gerrit Honthorst in Italia. Florence: Galleria degli Uffizi. ISBN 9788809805385.

- ^ Lincoln, Matthew (Spring 2016). "Sources for Gerrit van Honthorst's Italian Nickname". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 35 (3): 244–249. doi:10.1086/686710. S2CID 192807446.

- ^ Delavaux, Celine (2012). The Impossible Museum: The Best Art You'll Never See. Prestel. pp. 86–9. ISBN 9783791347158.

- ^ Boyle, Katherine. "National Gallery Acquires 'The Concert' by Dutch Golden Age Painter Honthorst." Washington Post. November 22, 2013. Accessed 22 November 2013.

Sources

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Honthorst, Gerard van". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 663–664.

- Brown, Christopher (1997). Utrecht Painters of the Dutch Golden Age. London: National Gallery. ISBN 1-85709-214-7.

- Filippo Baldinucci's Artists in biographies by Filippo Baldinucci, 1610–1670, p. 198 Internet Archive

External links

edit- 61 artworks by or after Gerard van Honthorst at the Art UK site

- Gerrit-van-honthorst.org Works by Gerrit van Honthorst

- Picture gallery at WGA

- Reproduction of The Laughing Violinist (in French)

- Works and literature at PubHist

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XII (9th ed.). 1881. pp. 143–144.

- Vermeer and The Delft School, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Gerard van Honthorst

- Dutch and Flemish paintings from the Hermitage, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Gerard van Honthorst (cat. no. 12)