Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia, is a rare, autosomal recessive disease, characterized by diaphyseal dysplasia and metaphyseal dysplasia of the long bones and refractory anemia.[2][3][1]

| Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | GHDD[1] |

| |

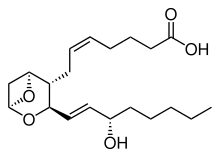

| Thromboxane A2 | |

It is associated with a deficiency of Thromboxane-A synthase,[4] which produces Thromboxane A2.

Although this disease is like Camurati–Engelmann disease where there is also diaphyseal dysplasia, there are, however, reasons to differentiate between the two diseases. As mentioned earlier, both diseases affect diaphysis, but Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia, affects both the diaphysis, and metaphyses.[1] Also, Camurati–Engelmann disease has no sign of defective haematopoiesis, but Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia is associated with a hematological abnormality.[5][6]

This is a rare disease and was characterized in 1988 by Ghosal in several children with anemia and bony dysplasia.[7][8] Later, in 2008, there was a discovery that a mutation in the gene TBXAS1 cause some of the distinct features in this disease such as increased bone density.[3][9]

Most cases are found in India and the Middle East area, likely meaning a shared gene pool.[10]

Symptoms and signs

editPeople with this disease often have varying degrees of the following symptoms.[1]

People with the disease often have overall inflammation with skeletal symptoms that could include increased bone density associated with dysplasia.[10] Specifically, the extremities are especially thick and long; bones can be seen with wide diaphyseal medullary cavities.[1] Most early manifestations of this disease are bowing of the legs and forearms with general weakness of the legs. The bowing of the legs is usually seen in adolescence, with the child often taking longer than average to walk. The increased bone density manifests with the skull with general widening of diploic space. Also, a thickened skull base suggests diaphyseal dysplasia, which can lead to sclerosis of the base of the skull.[5][11]

When it comes to blood, most symptoms can be summarized as defective hematopoiesis. It is speculated that this is due to the metadiaphyseal dysplasia of the long bones and fibrosis or sclerosis of the bone marrow. The symptoms can include corticosteroid-sensitive anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypocellular bone marrow, and myelofibrosis.[6][1] The key symptom here is progressive anemia, and symptoms like thrombocytopenia or leukopenia may be present with varying degrees of penetrance between patients.[12]

Causes

editGhosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder due to a mutation in both copies of the TBXAS1 gene on chromosome 7q34. The TBXAS1 gene codes for the enzyme Thromboxane-A synthase.[13] When known patients with the disease were sequenced for the TBXAS1 gene they had a homozygous missense mutation.[4] The TBXAS1 gene mainly transcribes in cells involved with the skeletal system and muscular system.

The increased bone density is due to lopsidedness between bones forming and bone resorption.[9]

This enzyme has a couple of essential functions in the body that, if removed, could lead to the symptoms observed with the disease. Thromboxane-A synthase is responsible for platelet aggregation and the regulation of bone mineral density. Thromboxane-A synthase regulates bone mineral density by influencing the two genes TNFSF₁₁ and TNFSF₁₁B, which encode for RANKL and osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor in osteoblasts, so if the regulation did not occur it consequently leads to sclerosis.[14]

Even though Thromboxane-A synthase is important for platelet aggregation it is important to note that patients with this disease do not have any bleeding problems.[4]

The refractory anemia also called corticosteroid sensitive anemia, is likely due to fibrotic scarring or sclerosis, which is the stiffening of the tissue when organ-specific tissue is replaced with connective tissue.[6] Thromboxane-A synthase also participants in the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway, which has effects on the prostaglandin E2 levels. A decrease in Thromboxane-A synthase leads to an increase in prostaglandin E2 levels which may affect erythroid precursor cells by suppressing them which likely leads to refractory anemia.[15]

There are still unanswered questions about the effect of a compromised TBXAS1 gene function and its affect in Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia.[4]

Diagnosis

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2024) |

Treatment

editBlood transfusions can treat the low levels of hemoglobin in patients, but symptoms usually come back in irregular intervals.[8] A consistent treatment most patients receive is a low-dose corticosteroid treatment, with a range between 0.1 mg/kg/day to 1.5 mg/kg/day to maintain hemoglobin and white blood cells at normal levels in the blood throughout life. The intervention of corticosteroid treatment is effective because patients can maintain healthy hemoglobin levels without the need for blood transfusions.[6][15] After steroid therapy, anemia and most hematological abnormalities resolved themselves after a couple of weeks.[5][15]

This disease must be identified early because the progression of some of the symptoms can be slowed down, and other signs of the disease can even be cured.

Even the more severe symptoms of the disease like the increase in bone density can be slowed. Some people treated early with the condition can achieve a healthy weight with thinning of dysplastic diaphysis to being close to normal.[5][11]

Walking abnormalities usually clear up with no signs of difficulty walking.[16]

History

editThere were five patients in early childhood had two significant symptoms of the disease characterized today as Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia. The two symptoms described were thick long bones of the extremities with features of diaphyseal dysplasia and anemia that was not responsive to hematinics. Broadening of the long bones, specifically in the diaphyses, is usually thought of as Englemann disease, but patients showed both diaphyses and the metaphyses to be affected. This minor detail when it comes to Englemann disease is essential because there is a consistent mention of the metaphyses of the long bones to have been unaffected. Even though some patients with Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia had difficulty walking, this is not a consistent symptom found with people affected by the disease, even though it is a crucial characteristic of Englemann disease.[7]

Some patients had low hemoglobin values experiencing Englemann disease. Anemia is a consistent feature of Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia with the severity of said anemia to include multiple blood transfusions.[7]

The gene responsible for Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia is likely TBXAS1. A genome-wide study was done on two families with the disease found that the likely culprits lie on the 7q33-34 chromosome. The region is made of the TBXAS1 gene, which is associated with bleeding disease, BRAF, which is associated with cancers, and ATP6VoA4, which is associated with renal distal tubular acidosis with sensorineural hearing loss.[2] One year later, in 2008, the mutation in the TBXAS1 gene was found to be the gene responsible for the disease. However, this means that since TBXAS1 encodes for the enzyme Thromboxane-A synthase, there are yet to be known functions of this enzyme when it comes to bone remolding.[4]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f "OMIM Entry - # 231095 - Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia ; GHDD". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b Isidor B, Dagoneau N, Huber C, Genevieve D, Bader-Meunier B, Blanche S, et al. (April 2007). "A gene responsible for Ghosal hemato-diaphyseal dysplasia maps to chromosome 7q33-34". Human Genetics. 121 (2): 269–73. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0311-1. PMID 17203301. S2CID 29595410.

- ^ a b Alebouyeh, Mardawig; Vossough, Parvanch; Tabarrok, Firouz (9 July 2009). "Early Manifestation of Ghosal-Type Hemato-Diaphyseal Dysplasia". Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 20 (5): 409–415. doi:10.1080/08880010390203945. PMID 12775540. S2CID 26922603.

- ^ a b c d e Geneviève D, Proulle V, Isidor B, Bellais S, Serre V, Djouadi F, et al. (March 2008). "Thromboxane synthase mutations in an increased bone density disorder (Ghosal syndrome)". Nature Genetics. 40 (3): 284–6. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.66. PMID 18264100. S2CID 2179041.

- ^ a b c d Datta K, Karmakar M, Hira M, Halder S, Pramanik K, Banerjee G (December 2013). "Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia with myelofibrosis". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 80 (12): 1050–2. doi:10.1007/s12098-012-0872-z. PMID 22983925. S2CID 35709801.

- ^ a b c d Arora R, Aggarwal S, Deme S (March 2015). "Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia-a concise review including an illustrative patient". Skeletal Radiology. 44 (3): 447–50. doi:10.1007/s00256-014-1989-0. PMID 25172219. S2CID 11175313.

- ^ a b c Ghosal SP, Mukherjee AK, Mukherjee D, Ghosh AK (July 1988). "Diaphyseal dysplasia associated with anemia". The Journal of Pediatrics. 113 (1 Pt 1): 49–57. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80527-4. PMID 3385529.

- ^ a b Ghosal, S. P.; Mukherjee, A. K.; Mukherjee, D.; Ghosh, A. K. (July 1988). "Diaphyseal dysplasia associated with anemia". The Journal of Pediatrics. 113 (1 Pt 1): 49–57. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80527-4. ISSN 0022-3476. PMID 3385529.

- ^ a b Geneviève, David; Proulle, Valérie; Isidor, Bertrand; Bellais, Samuel; Serre, Valérie; Djouadi, Fatima; Picard, Capucine; Vignon-Savoye, Capucine; Bader-Meunier, Brigitte; Blanche, Stéphane; de Vernejoul, Marie-Christine (March 2008). "Thromboxane synthase mutations in an increased bone density disorder (Ghosal syndrome)". Nature Genetics. 40 (3): 284–286. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.66. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 18264100. S2CID 2179041.

- ^ a b Jeevan A, Doyard M, Kabra M, Daire VC, Gupta N (April 2016). "Ghosal Type Hematodiaphyseal Dysplasia". Indian Pediatrics. 53 (4): 347–8. doi:10.1007/s13312-016-0851-y. PMID 27156553. S2CID 9030177.

- ^ a b Mondal RK, Karmakar B, Chandra PK, Mukherjee K (March 2007). "Ghosal type hemato-diaphyseal dysplasia: a rare variety of Engelmann's disease". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 74 (3): 291–3. doi:10.1007/s12098-007-0047-5. PMID 17401271. S2CID 42815531.

- ^ Kini PG, Kumar S, Moideen A, Narain AT (January 2018). "Ghosal Hemato-diaphyseal Dysplasia: A Rare Variety of Hypoplastic Anemia with Good Response to Steroid Therapy". Indian Journal of Hematology & Blood Transfusion. 34 (1): 181–182. doi:10.1007/s12288-017-0818-8. PMC 5786615. PMID 29398828.

- ^ "OMIM Entry - * 274180 - Thromboxane A Synthase 1; TBXAS1". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ^ Ciftciler R, Buyukasık Y, Saglam EA, Haznedaroglu IC (August 2019). "Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia with autoimmune anemia in two adult siblings". Transfusion and Apheresis Science. 58 (4): 449–452. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2019.04.027. PMID 31395426. S2CID 199507803.

- ^ a b c John RR, Boddu D, Chaudhary N, Yadav VK, Mathew LG (May 2015). "Steroid-responsive anemia in patients of Ghosal hematodiaphyseal dysplasia: simple to diagnose and easy to treat". Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 37 (4): 285–9. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000279. PMID 25374284. S2CID 2696383.

- ^ Alebouyeh, Mardawig; Vossough, Parvanch; Tabarrok, Firouz (July 2003). "Early manifestation of Ghosal-type hemato-diaphyseal dysplasia". Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 20 (5): 409–415. doi:10.1080/08880010390203945. ISSN 0888-0018. PMID 12775540. S2CID 26922603.