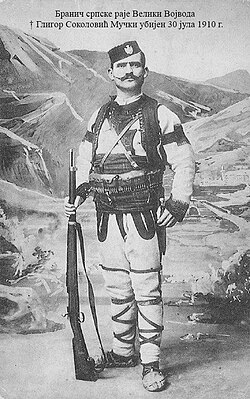

Gligor Sokolović (Serbian Cyrillic: Глигор Соколовић[c]; 17 or 5 January 1870 or 1872[1] – 30 July 1910]) was one of the supreme commanders (Great Voivode) of the Serbian Chetnik Movement, that fought the Ottoman Empire, Bulgarian, and Albanian armed bands during the Macedonian Struggle. He was one of the most famous Chetniks,[2] and the foremost in Western Povardarie.[3] In Bulgaria he is considered a Bulgarian renegade who switched sides, i.e. (sic) Serboman.[4]

Gligor Sokolović | |

|---|---|

Vojvoda Sokolović | |

| Birth name | Gligor Sokolov Ljamević Nebregovski[c] |

| Nickname(s) | Gligor Sokolović – Nebregovski |

| Born | 17 or 5 January 1870 or 1872 Nebregovo, Ottoman Empire (now within Dolneni Municipality, North Macedonia) |

| Died | 30 July 1910 Macedonia, Ottoman Empire |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1896–1910 |

| Rank | Great Voivode (Veliki Vojvoda) |

| Unit | Western Povardarje |

| Battles / wars | Macedonian Struggle |

After murdering a local Ottoman lord, Sokolović went into the woods with some friends and formed a guerrilla unit which would target Ottomans. He then joined the Bulgarian revolutionary organizations of SMAC and IMRO,[5] and fought throughout the wider Macedonia region. After the Ottomans' suppression of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising in 1903, he, like many others, fled to Serbia. He was acquainted with Dr. Gođevac, one of the founders of the Serbian revolutionary organization that sought liberation of Macedonia, and became one of its supreme commanders that would fight in the Prilep region. With the Young Turk Revolution, he became a deputy of the National Assembly of the Serbs in Turkey. He was killed in 1910 by the Ottoman government.

Life

editEarly life

editSokolović was born in 1870[6] in the village of Nebregovo, near Prilep, under the Ottoman Empire (now part of Dolneni, North Macedonia).[7] His father was Sokol Lamević (1833–1903). He grew up without education.

At a young age, Sokolović killed a noted Turk from Prilep, Ali-Aga, the property intendant of Avdi-Pasha, who held villages around Babuna, and was a notorious persecutor of Christians.[7]

Murder of Ali-Aga and entering guerrilla lifestyle

editAvdi-Pasha, the Lord of Babuna, had an infamous chiflik intendant in his service, Ali-Aga, who was a notorious persecutor (zulum) of Christians.[6] Ali-Aga had cancelled weddings, as the first day of his arrival was to be in his honour only.[6] When Ali-Aga gathered the tax, he took an amount that suited him, and never followed any law. Ali-Aga beat villagers whose gibanica (pastry) was not fat enough.[6] He ordered villages to slay sheep just in order to clear his rifle barrel with the tallow.[6] The villagers had none at their side, so five villages (Stepanci, Prisad, Smilovci, Nikodin, Krstec) secretly conspired to murder Ali-Aga, but no one dared to fulfill the task.[6] Then, Gligor Sokolović, aged 25, from a sixth village, accepted it.[6]

Sokolović, with his friend Tale Šejtan, prepared an ambush on the road of Babun, and waited for several days.[6] One morning the villagers of Stepanci came and told them that Ali-Aga had just turned to collect tax from the farms.[6] Tale climbed a tree and had a full view of the surroundings, while Sokolović went and lay with his gun on the end of the road.[6] As Ali-Aga advanced on his horse, Sokolović carefully aimed and shot, and Ali-Aga fell hard to the ground.[6] His horse screamed and fled towards Prilep, and Sokolović and Tale hurried to disappear into the forest, even though no one had seen them.[6] Prilep was soon alarmed, and an army went into pursuit.[6] Sokolović had returned to the village by the night, and the villagers quietly greeted him for his deed.[6]

Forces arrived in Nebregovo and searched through the houses.[8] When they entered Sokolović's house, he quietly waited while they found nothing.[8] As soon as the troops had left the village, Sokolović went back to the forest and took his hidden gun, and he began guerrilla warfare in the summer of 1895, and he would never look back on the village life.[8] He gathered a few friends: Đorđe Palaš from Prisad, Riste Todorović-Šika from Drenovci, and Koce from Omorani, that would form a band.[8] As they did not want to be far away from home, they moved through the forests of Babun and Nebregovo, and ate what the shepherds had prepared for them in the heights of the village areas.[8] In the fall, when the forests became thinner and the first snow made traces, they were forced to flee the site, and they had heard that in Bulgaria, some kind of committee for the struggle against the Ottoman Empire had been founded.[8] Hungry, and pursued, they joined the Bulgarian revolutionaries, where they would not have much rest.[8]

1896–1903

editFighting in Salonica and visit to Nebregovo

editOn Atanasov dan (18 January), 1896, his band of 9 friends were led by Dimo Dedoto (Supreme Macedonian Committee), from Thessaloniki back across the border.[8] There was heavy snow, and severe cold; Sokolović had his feet severely frozen, swollen and sore.[8] He managed to Nebregovo.[8] Sokolović was not allowed to see his family, so he went to his friend, Stanko Bogojević, in belief that he would not be noticed.[8] The frozen flesh of his feet fell of, and they were healed with grass.[8] The village heard that Sokolović had returned.[8] Stanko, fearing for his family, went to Sokol, Gligor's father, and told him that he could not care for the hajduk any more.[8] Sokol came for his son, and when he saw his wounds in the light, he cried.[8] Sokolović was taken to his father's house and there he healed.[8] When snow fell on Babuna again, he left for the forest again, gathering a small band from old friends.[8]

In springtime, there was time for the Turks to collect livestock tax from the shepherds, who tried to hide the animals in caves and the heights, but the Turks searched there too.[9] One day, the begs (honorary title, "sir") arrived in Drenovci to a shepherd who told them that there were none left, but the one beg, unbelieving, went into the hut to inspect.[9] The beg was shot in the head, and the others left the premises running – in the hut was Sokolović and his band.[9]

Fighting in Mariovo and Pirin

editThe band could not stay in Babuna, and crossed into Mariovo, and on the way they left the bodies of four begs from Vitolište, but they could not stay in Morihovo for long, and they retreated to Belica in Poreče.[9]

One day, there came a message that two Turkish merchants from Ohrid would travel through the Babuna to Veles.[9] Sokolović had the knowledge and time to prepare an ambush before Stepanci.[9] The merchants came on horses, and they had silver revolvers in their belts – Sokolović shouted "Throw your pistols!" in Turkish ("Чикараз алтипатлак!"), jumping in front of them.[9] They let go off their guns, and were killed.[9] Pursuits were made in all villages, and Sokolović was forced to flee towards the Bulgarian border once again.[9] To spare his family from retaliation, he never returned to Babuna.[9] He fought in the Salonica Vilayet on the Pirin mountains, where he befriended Greek bandits, from whom he adopted opanke with longer tassels (tsarouhi).[9]

Ilinden Uprising and moving to Serbia

editWhen the Uprising broke out in June 1903, Turks from Desovo, while they understood that Sokolović was with his bandits, waited outside the house of Sokol until he came home from Prilep and killed him.[9] They took his severed nose and eyes with them as a sign of vendetta.[9] Sokolović was at the time in Bulgaria, as part of an Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) detachment of 400–500 soldiers, of which commanders where Sotir Atanasov, Atanas Murdzhev, Dimitar Ganchev and Nikola Pushkarov.[10] Hearing of his father's death, he gathered a band and turned to repay his father, but he only reached Vardar, which was cut off by the Ottoman army.[9] The destroyed bands fled towards Bulgaria and Serbia.[9] Sokolović also needed to depart, and he sent a letter to his brother with a bandit, saying: "I was on my way to return blood but there were many askeri on the Vardar. I retaliated [for his death], but I have not avenged him."[11]

He turned towards Kyustendil, but when he reached Gyueshevo, the first village after the Bulgarian border, a group of Bulgarians tried to disarm them, and Sokolović began to fight them.[11] Wounded, he returned to Turkish territory with his 8 fighters in order to reach the Serbian border.[11] In Buštranje, an old rebel base, he crossed into Serbia.[11] Naum Marković, Jordan Severković, Koce Mrguška, from Drenovac; Ilija Močko from Prilep; Josif from Bela Crkva, and Ilija Jovanović, did not leave their commander.[11] Worn down, with torn shoes and clothes, smeared in mud, and with long beards, they reported themselves to the Serbian border patrol.[11]

The band was taken to Vranje, their weapons were left at the Tabana café, and they were sent to Belgrade, where the Serb Chetnik Movement committee awaited them.[11] At their arrival, they were sent to prison as they were suspected Bulgarian komiti.[11]

1903–1910

editArrival at Belgrade and meeting with Dr. Gođevac

editA bricklayer, Spasa Kostić, came running to the office of Dr. Gođevac, saying that Voivode Gligor Sokolović and his fighters had returned from the battlefield and had been falsely imprisoned by the Belgrade Police, and that Sokolović was wounded in the head.[12] Dr. Gođevac quickly contacted the borough manager, and the band was immediately released.[12] In Palilula, at the Dva Pobratima café, owned by a Nikola from Kruševo, Sokolović found his brother who worked in the Belgrade water system.[12] Dr. Gođevac had not yet visited the Voivode whom he had freed, so he walked the Varoš-kapija (an historical neighbourhood) at noon, and Vasa Jovanović (minister) told him that a group of chetniks had dinner at Razman's aščinica (traditional restaurant).[12] The baker, Damče, took Dr. Gođevac in and pointed at where Sokolović sat.[12] At a fat-soiled table sat three chetniks in front of a steaming large bowl with pasulj.[12] Upon noticing Vasa Jovanović, the three jumped up, and a puzzled Sokolović gave his hard hand, full of calluses.[12] Sokolović was young, with bright blue eyes, timid in his moves, humble, he seemed to have nothing hajduk (brigand) about him. Only his great stature gave light of enormous power.[12] After he had finished his meal, Vasa Jovanović escorted him to Dr. Gođevac.[12] Dr. Gođevac, who was almost disappointed since the encounter, asked him about the head wound.[12] Sokolović gave an embarrassed smile and replied -"It's nothing...", "Who wounded you?", -"We had a fight..." – he was suspicious, and avoided long conversations.[12] Dr. Gođevac began healing his wounds; his head wound was a result from a gun stock blow, and though it was not severe, it had been neglected.[6] Little by little, Sokolović began opening himself up, telling the story of his life.[6]

When Sokolović's wound was healed, he was sent to Stara Bogoslovija (between St. Michael's Cathedral and Kalemegdan, towards Hotel National) where more than 50 fighters stayed.[11] He wintered in Belgrade, and spent his time in the "Crni konj" café, where many other displaced Serbs gathered.[13] The Stara Bogoslovija quarter served as a barrack for komiti.[14]

Serb Committee sends first bands

editOn Đurđevdan (23 April), 1904, Bulgarian students travelled to Belgrade to hold a congress.[15] This was after negotiations between the Bulgarian and Serbian committees about a joint Serb-Bulgarian uprising had failed after more than 50 meetings in a period of 4–5 months.[16] The Bulgarian students and the Serbian side constantly stressed the need for Serb-Bulgarian brotherhood.[15] After the students had left, it was unearthed that most of these were in fact members of the Bulgarian committee, who sought to find their companions and lead them back to Bulgaria.[15] Three of them were wholly assigned to persuade Gligor Sokolović to return to Bulgaria, but he refused.[15] They also met with Stojan Donski.[15]

On 25 April, two bands (četa) of some 20 fighters under voivodes Anđelko Aleksić and Đorđe Cvetković swore oath in a ceremony of the Serbian Chetnik Committee (Dr. Milorad Gođevac, Vasa Jovanović, Žika Rafailović, Luka Ćelović and General Jovan Atanacković), with prota Nikola Stefanović holding the prayers.[14] The Committee had prepared the formation of the first bands for a number of months.[14] The Chetniks were sent for Poreče, and on 8 May they headed out from Vranje, to Buštranje, which was divided between Serbia and Turkey.[17] Vasilije Trbić, who guided them, told them that the best way was to go through the Kozjak and then down to the Vardar.[18] The two voivodes however, wanted the fastest route, through the Kumanovo plains and then to Četirac.[18] They managed to enter Turkish territory but were subsequently exposed in the plain Albanian and Turkish villages, and the Ottomans closed in on them from all sides, and they decided to stay on the Šuplji Kamen, which gave them little defence instead of meeting the army on the plains; in broad daylight, the Ottoman military easily poured bombs over the hill and killed all 24 of the Chetniks.[19]

Second wave

editAfter receiving the news in Belgrade, the Chetnik activity did not stop; four new bands were prepared for crossing the border.[20] Velko Mandarchev, from the Skopje field, became the voivode of a band that moved into Skopska Crna Gora.[20] The more experienced and bold Gligor Sokolović became the voivode of a band that would fight in the Prilep region (Prilepska četa).[7][20] Rista Cvetković-Sušički, a former friend and voivode of Zafirov, was sent for Poreče where Micko Krstić impatiently waited for him with the band.[20] Poreče was a source for the rebels; every villager was a martyr and hero, and although Poreče was small, it beat off all attacks, and from it, troops entered all sides, as an effectuation for the struggle.[20] The fourth band was firstly sent to Drimkol, Ohrid, its voivodes being Đorđe Cvetković and Vasilije Trbić.[20]

On the night of 19 July, the four bands crossed the border.[20] They went a secure route which had been put forward by Trbić and Anđelko.[20] They did not rush, and spent days in Kozjak and villages of the Pčinja.[20] They went fast and lightly in the night, and carefully descended towards the Vardar transition.[20] In the village of Živinj, in the middle of the junction, they encountered Bulgarian Voivode Bobev; the meeting at first was sudden and unpleasant, but quickly became friendly and festive.[20] Voivode Bobev assured them that he was happy that they would fight together, and took the bands to the village of Lisičja, where they would cross over the Vardar.[20] Only Sokolović suspected a fraud, but went reluctantly.[20] A sudden Ottoman chase urged them to abandon the route on the river coast of Pčinja, and to cross Vardar at one of its confluences, as they had intended at first.[20] On the night of 31 July, in the village of Lisičja, to no avail, a large Bulgarian ambush waited for Bobev to lead the Serbs to their hands – to terminate the Serbian Chetnik Movement.[21]

In the village of Solpa, they dried their clothes on the warm summer morning, and rested in the boxwood shrubs and ate wet bread.[21] Bobev, who was not allowed to leave them as part of the ambush, was still with them.[21] On the next day, 2 August, the bands crossed through Drenovo, and climbed the Šipočar mountain in a long line, where they would rest and drink fragrant milk of the Vlachs.[21] For three days they freely stayed in the mountain and watched the horizon, and routinely looked out, and then climbed to the higher Dautica mountain.[21]

Sokolović, troubled and bothered by Bobev's presence, did not want to go further and took his band towards Babuna.[21] The three bands that stayed, followed by Bobev, descended into Belica.[21] There they found a number of Bulgarian bands, led by Voivode Banča, who told them to call on Micko, a lord of Poreče.[21] The Serbs awaited him, not sensing a deceit.[21] But Trbić, who had always sought the background in things, found out from a drunk Bulgarian friend, whom he had been drinking with for an hour, that there was a plot against them.[21] Trbić told a villager assistant to report to Micko not to come.[21] After learning this, the band of Trbić and Đorđe Cvetković turned to Demir-Hisar.[21] Mandarčević and Sušički stayed in Belica, ready for betrayal.[21] In the mountain village of Slansko they found yet another Bulgarian band, of Voivode Đurčin, who kindly, but with the intent to follow them, sent with them two followers to Cer, in Demir-Hisar.[21]

In the meantime, in Belgrade, there was still hope that the Serbs and Bulgarians would work together in Macedonia; however, in Macedonian villages, there began massacres. On the night of 6 August, Bulgarian major Atanas Babata and his band entered the Serbian village of Kokošinje, where they were searching for people that were condemned to death by the Bulgarian Committee. The Bulgarian band demanded that the village priests and teachers renounce their Serbian identity, but they refused, and they massacred over 53 people. A servant of one of the teachers, who had managed to hide, set out to find the band of Jovan Dovezenski, who he had heard was crossing the border. The teacher's servant found another Serbian band, that of Jovan Pešić-Strelac, which had learned of the Bulgarian atrocities of Babota, but also of those of Jordan Spasev, who had killed members of the notable Dunković family on 11 August.[a]

The Serbian Chetniks in Poreče and Demir-Hisar, constantly followed by Bulgarians, did not know of the massacres.[22] The hungry and tired band of Đorđe Cvetković arrived at the village of Gornji Divjaci, where they were hosted by the villagers who had brought cheese and rakija.[22] They rested in sheets of sheep skin, and the village children came with bread and listened to their stories.[22] Cvetković, Trbić and Stevan Ćela rested in the house of the village leader, and ate several meals.[22] In the next morning, Trbić walked through the yard and went down some stairs, and saw an Ottoman jandarma whom he shot, who was then buried in the forest.[22] The rest ended and the band assembled and walked the river across the mountain.[22] They arrived at the village of Cer the next day where they also found Bulgarians, and the Bulgarian voivodes Hristo Uzunov and Georgi Sugarev joined their company.[22]

In the mountainous village of Mramorac, where Petar Chaulev had set up camp in the forest, Trbić band were told that the Bulgarian Committee had prohibited them to go to Drimkol.[23] On the same day, 14 August, the Bulgarians had killed Serbian priest Stavro Krstić, which the Chetniks later learnt from the villagers.[b] Far from the other bands, without help, tricked and surrounded, the band understood their situation.[23] Chaulev informed them of their disarmament and the Bulgarian Committee's verdict of crime against the Bulgarian organization.[23] They were only shouted at, as they were saved by some ethnic Serb voivodes in the Bulgarian bands: Tase and Dejan from Prisovjan and Cvetko from Jablanica in Debar, who were bound by oath to the Bulgarian Committee, but nevertheless openly defended the Serbian Chetniks, and friends, whom they had wintered together with in Belgrade.[23] They awaited Dame Gruev, the second leader of the Bulgarian Committee after Sarafov, who would arrive from Bitola.[23] Gruev and his escort arrived as village priests on a night.[23] Trbić knew Gruev from the Kruševo Uprising and from an encounter in Serava.[23] Trbić used their acquaintance and memories, reminding Gruev of the common revolutionary fight and his childhood, when Gruev was a cadet of the Society of Saint Sava in Belgrade, and an apprentice in the printing house of Pero Todorović, which was called Smiljevo after Gruev's birthplace.[23]

Fighting

editHe fought mainly Bulgarian forces.[7] Under his command, the Prilep, Kičevo, Veles, Poreče regions were cleared of Bulgarian forces.[7] When the Young Turk Revolution broke out (1907–1908), and there was a temporary peace in Macedonia, the Young Turks gave Serbs more rights.[7]

Young Turk revolution and death

editThe Serbian leaders in Turkey held a conference in Skopje, August 1908, and passed a decision to found the Serbian Democratic League, whose objective was "...to aid the establishment of civil freedoms and constitutional life." The National Assembly of the Serbs in Turkey was held in Skopje from 2 to 11 February 1909, and the Constitution of the Serbian National Organization in the Ottoman Empire was passed; the requirements concerning education, political and economic life of the Serbs in Turkey were proclaimed. Besides the Chief Committee seated in Skopje, there were four district committees: for the Eparchy of Raška and Prizren, for the Skopje eparchy, for the Manastir Vilayet, and for the Salonica Vilayet. Gligor Sokolović, chief, was one of the deputies.[24]

However, the Young Turks changed politics and turned against the Serbs.[7] The Turks gave Sokolović a bodyguard, and when he stopped to drink water from a fountain, they killed him.[7]

His eldest son, Andon, died as a Serbian volunteer in the First Balkan War.[7] Sokolović was the maternal uncle of Blaže Koneski, a Yugoslav poet and major Macedonian linguist.[10]

See also

editAnnotations

edit- ^ Massacres in Kokošinje and Rudar: In the meantime, in Belgrade, there was still hope that the Serbs and Bulgarians would work together in Macedonia, however, in Macedonian villages, there began massacres.[25] On the night of 6 August, Bulgarian major Atanas Bobota and his band entered the Serbian village of Kokošinje, where they were searching for people that were condemned to death by the Bulgarian Committee.[25] Prota Aleksić stayed in his house, with Jovan Cvetković, the new village teacher from Kumanovo, and his nephew Milan Pop-Petrušinović.[25] Bobota entered the house, and Prota Aleksić's servant Mihajlo Miladinović hid on the attic, listening to the shouting and hearing that daskal Dovezenski had gathered a band in Serbia.[25] The three were taken out by the road, tied with kmet Trajko Car, elder Mita Pržo, and the elder's son Grozdan, and grandchild Gavo, and youngster Jovan Ivanović-Čekerenda.[26] Babota's soldiers awaited his further commands, he turned to the teacher: "Come on, tell me that you are Bulgarian, and you can continue be a Serb, and I will spare your life", but he refused.[26] Babota put his bayonnet to the breast of Cvetković, and to his astonishment, the teacher jumped on it with all his weight.[26] The massacre began, and 53 people were killed.[26] Babota then searched in the school, and on the second floor they found an old man, teacher Dane Stojanović, who also had been condemned to death by the Bulgarian Committee.[27] After Babota and his band had disappeared, the houses opened and the women screeched, and the silent villagers moved the bodies.[27] Servant Miladinović immediately left the village and began his search of Dovezenski.[27] The next day, Babota and his whole band returned, and he held feral speeches in the inn by the school, in front of all villagers, as Dane Stojanović, too, had refused renouncing his Serbian identity.[27]

On this same day, 7 August, Dovezenski, code named Jovan Slovo Želigovac, had crossed the border.[27] Dovezenski, who had been to church school in Belgrade, and had been a teacher in his village, had for 7 years lost close people because of their identity (Serbian).[27] When in March 1904, Bulgarians killed his godfather Atanas Stojiljković in his birthvillage of Dovezance, Dovezenski closed his school and went to Vranje, where he demanded a permit to form a Chetnik band.[27] Servant Miladinović found the band of Jovan Pešić-Strelac, which was composed of Chetniks from Toplica, Vranje frontier soldiers, and people from Old Serbia.[27] While descending the Pčinja, they learnt of the Kokošinje massacre, which the whole Kratovo and Kumanovo regions uttered Babota's name, but also heard the name of Jordan Spasev, a Bulgarian reserve soldier.[27]

The affluent Serb family Dunković, originally from Berovo, which had held the resistance of the Kratovo village of Rudar against the Bulgarian Exarchate and Bulgarians, had been condemned to death by the Bulgarian Committee.[28] In the dawn of 11 August, Jordan Spasev and his 30 komiti surrounded the waqf mill of the Vakov-Nenovce village.[28] The villagers were tortured and killed by the komite.

- ^ Murder of priest Stavro Krstić: On the same day as Trbić arrived at Mramorac, 14 August, the Bulgarians had killed Serbian priest Stavro Krstić, whose priest father Stojan had earlier been killed by Bulgarians.[23] The Bulgarians had found out that he would bless the house of his godfather in Podgorac on The Assumption.[23] The godfather was out, and they waited until the godfather's wife had left the house, and then entered the house where they found the priest reading prayers.[23] They shot him in the chest, and wounded he shut the door and went outside the house with a revolver, where he was shot a second time and died.[23] In Mramorac the Serbian Chetniks learnt of his death from the villagers.[23]

- ^ Name: His name used in Serbian is Gligor Sokolović (Глигор Соколовић), in Bulgarian Gligor Sokolov (Глигор Соколов), in Macedonian Gligor Sokolović (Глигор Соколовиќ). Sokolov(ić) is a patronymic, from his father, Sokol. Gligor's family name in Serbian is Lamević (Ламевић) or Ljamević (Љамевић), in Bulgarian Lamev (Ламев).

Notes

edit- ^ Войвода Глигуръ Соколовъ. Единъ отъ най-отличнитѣ войводи, стрѣлецъ чудесенъ. Роденъ на 17-й Януари 1870 г. въ с. Небрѣгово (Прилѣпско).... [1] Archived 11 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1, 1973, p. 512

- ^ Glas Javnosti, Prvi gorski štabovi Archived 3 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 3 March 2003

- ^ Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996 Archived 14 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, 67

- ^ Николов, Борис Й. (2001) Вътрешна македоно-одринска революционна организация. Войводи и ръководители (1893–1934). Биографично-библиографски справочник, София. p. 152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Krakov, p. 107

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Živković 1998

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Krakov p. 108

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Krakov, p. 109

- ^ a b Кръстю Лазаров. Революционната дейност в Кумановско Archived 6 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. promacedonia.org (in Bulgarian)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Krakov, p. 110

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Krakov, p. 106

- ^ Nusic 1966, p. 134

- ^ a b c Krakov, p. 150

- ^ a b c d e Krakov, p. 147

- ^ Krakov, p. 146

- ^ Krakov, p. 154

- ^ a b Krakov, p. 155

- ^ Krakov, pp. 161–164

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Krakov, p. 166

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Krakov, p. 167

- ^ a b c d e f g Krakov, p. 172

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Krakov, p. 173

- ^ The Serbs and the Macedonian Question Archived 6 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine; Rad Narodne skupštine otomanskih Srba, februar 2–11, 1909 /The Sessions of the National Assembly of the Ottoman Serbs/ (Skopje, 1910).

- ^ a b c d Krakov, p. 168

- ^ a b c d Krakov, p. 169

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Krakov, p. 170

- ^ a b Krakov, p. 171

References

edit- Krakov, Stanislav (1990) [1930], Plamen četništva (in Serbian), Belgrade: Hipnos

- Živković, Simo (December 1998), "SAKUPI SE JEDNA ČETA MALA", Srpsko Nasleđe Istorijske Sveske (12), Belgrade: PREDUZEĆE ZA NOVINSKO IZDAVAČKU DELATNOST „GLAS“ d.d.o., archived from the original on 3 March 2012, retrieved 2 February 2010

- Paunović, Marinko (1998), Srbi: biografije znamenitih : A-Š, Belgrade: Emka, pp. 231–232, ISBN 9788685205040, archived from the original on 8 November 2023, retrieved 22 September 2016,

Глигор Соколовић

- Nušić, Branislav Đ (1966), Sabrana dela, vol. 22, Belgrade: NIP "Jež", p. 134,

Глигор Соколовић

- VESTI online (18 December 2011), Prvi beogradski četnici, Belgrade, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 23 February 2012

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vučetić, B. (2006) "Srpska revolucionarna organizacija u Osmanskom carstvu na početku XX veka", Istorijski časopis, no. 53, pp. 359–374[permanent dead link].

- Simijanović, J. (2008) "Okolnosti na početku srpske četničke akcije – neki pokušaji saradnje i sukobi četnika i komita u Makedoniji", Baština, no. 25, pp. 239–250.

- Rastović, A. (2010) "Macedonian issue in the British Parliament 1903–1908", Istorijski časopis, no. 59, pp. 365–386[permanent dead link].