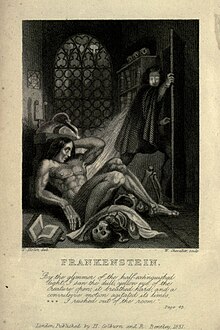

When Mary Shelley's Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published in 1818, the novel immediately found itself labeled as Gothic and, with a few exceptions, promoted to the status of masterpiece.

The Gothic wave began with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), followed by aristocrat William Beckford's Vathek (1787),[1] and peaked with the works of Ann Radcliffe (1791–1797). After a few spurts with The Monk by Lewis (1796), it has since been in marked decline. After that, the novel moved on to something else, becoming historical with Walter Scott, and later truly romantic with the Brontë sisters. The Gothic did, however, persist within the Victorian novel, particularly in Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens, but only as a hint.[2]

Before 1818, or at the time of Frankenstein's composition, the genre was considered in bad taste, if not downright laughable. In accordance with Edmund Burke's warnings,[3] the line between the fantastique and the ridiculous seemed to have been crossed. Coleridge, familiar with the Godwins and thus with Mary Shelley, wrote as early as 1797, in reference to M. G. Lewis's The Monk, that "the horrible and the supernatural [...], powerful stimulants, are never required, unless for the torpor of a drowsy or exhausted appetite". He criticized "tiresome enemies, insubstantial characters, screams, murders, subterranean dungeons, [...] imagination and thought out of breath, [...] vulgar and low taste."[4] In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen, in 1817, had Henry Tilney give Catherine Morland a lesson in common sense:[5] "Remember that we are English, that we are Christian. Appeal to your understanding, your appreciation of verisimilitude, your sense of observation [...] does your education prepare you for similar atrocities?"[6] In other words, the critics embraced the Incredulus odi,[7] which led to an overdose of the marvelous, whose very nature, as Walter Scott pointed out in 1818, is to be "easily exhausted.[8]

Frankenstein's immediate and undeniable success was based on foundations that differed from those of its predecessors, if not in appearance, then at least in essence. The novel substitutes horror for terror, divests itself of all wonder, favors internalization and anchors itself in rationality, to the point where its gothic style becomes almost realistic and has revelatory value.

The Gothic novel

editThe great Gothic wave, which stretches from 1764 with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto to around 1818-1820, features ghosts, castles and terrifying characters; Satanism and the supernatural are favorite subjects; for instance, Ann Radcliffe presents sensitive, persecuted young girls who evolve in a frightening universe where secret doors open onto visions of horror, themes even more clearly addressed by M. G. Lewis at the age of twenty. His novel's youthful ardor and satanism gave the genre the extreme model it sought. After these excesses of terror, the genre could but slowly decline,[9] and Frankenstein, through its originality, struck a decisive blow.[2]

Terror and horror

editWhen Edmund Burke addresses the notion of the "sublime", he describes the feelings inspired in the viewer or reader in terms of "terror" or "horror", but, it seems, without making much distinction between the two, although "terror" is the word most often used.[10]

Substitution of horror for terror in Frankenstein

editMax Duperray explains that the choice of the term "horror" served to distinguish a later school within the Gothic movement, which Frankenstein is partly part of: "[...] whereas the early novels separate good and evil with an insurmountable barrier," he writes, "the later ones usher in the era of moral ambiguity, involving the reader more deeply in the mysteries of the transgressive personalities of their heroes-scoundrels."[1]

The first great gothic wave based its effects on what was more commonly referred to as "terror", the desired feeling being "fear" or " fright" (frayeur),[11] hence the use of well-known devices, which Max Duperray calls "a machinery to frighten."[1] There are still many hints of this in Frankenstein: Victor works in a secret laboratory plunged into darkness; his somewhat remote house is streaked with labyrinthine corridors; he enters, without describing them, into forbidden vaults, he breaks into cemeteries soon to be profaned; the mountains he climbs are pierced by sinister caves, icy spaces stretch to infinity, lands and oceans tumble into chaos, etc.[12]

The emancipation of Gothic wonder

editHowever, apart from the very young man's brief and unsuccessful foray into esotericism, there is nothing reminiscent of the supernatural, the ghostly.[13] There are apparitions, but they are those of the monster, who appears when he is least expected, following his creator step by step without much vraisemblance (likelihood), an expert in concealment and an excellent director of his own manifestations. The reader is transported far from his familiar surroundings by the exoticism, for the 19th century, of Switzerland, Bavaria, Austria and so on. But if they are disoriented, it's by something other than traditional Gothic wonder. The only manifestations that are remotely reminiscent of an extra-human power are those of nature, the storm, the lightning.[14] Moreover, Victor Frankenstein is careful to point out that his education has rid him of all prejudice, that the supernatural holds no appeal for him, in short that his knowledge and natural disposition lead him along the enlightened path of rationalism.[13]

Mary Shelley, at least initially, seems to substitute horror for terror. Horror is based on repulsion, and it is well known that Mary was attracted to the macabre as a young girl.[Note 1][15] It is death, its manifestations and attributes, that take the center stage: thus, what was vaulted in earlier Gothic becomes a mortuary vault, what was a dungeon becomes a mass grave and charnel house, what was a torture tray becomes a dissection table, what was torn clothing is metamorphosed into shreds of flesh. The medieval castle has disappeared; in its place, an isolated office in a town unknown, at least to the English reader, then a filthy laboratory on an almost deserted northern island.[16]

The physical horror of appearances

editWhat's more, the horror comes to life in the figure of the monster who, although alive, has lost none of his cadaverous characteristics, and it's this complacently supported description of his physical appearance that is one of the driving forces behind the action, since it provokes social rejection, hence revenge, the reversal of the situation, and so on. The horror of the eyes, eyelids, cheeks, lips, colors, mummification, open body, functional organs but gangrenous and infested with morbid decay, is further accentuated by the unfinished making of a female creature: although not explicitly stated, the text suggests that it is precisely at the moment when the woman's genitals are to be placed that Victor's rage leads him to lacerate, tear, destroy, restore the assembled shreds to chaos. Here we find the symbolism of the dream, where the love kiss is transformed into a fatal incestuous embrace, where desire is the bearer of death.[17]

Frankenstein's work unleashes into the world of men a creature of gigantic hideousness, scruffy, cadaverous, and it stops when it was not far from finding its fulfillment in the possibility of a monstrous lineage. It is appearance alone that arouses horror, since the monster possesses the intellectual, emotional and sentimental qualities of uncorrupted man.[18] Society bases many of its reactions, and the behavior of the human community depends essentially on the way things look,[19] a fragile equilibrium based on the gaze of one on the other and of the other on the other.[20] Alienation - the feeling of being different - is at the heart of Mary Shelley's Gothic.[17]

During the implementation of Victor's project, horror is adorned with a scientific alibi. Mary Shelley places the act of creation in an experimental context, naming the disciplines involved: physics, chemistry and the natural sciences. A sincere alibi, she and her parents, companion and friends have always been rationalists. Moreover, Victor is presented as a relentless, obstinate researcher, whose intellectual activity is clearly compartmentalized: nothing else interests him, literary and artistic culture, the so-called moral sciences being left to Clerval.[21]

Return to terror, but internalized

editOnce the act of creation is complete, the Gothic aspect of the novel leaves the stage of the outside world - with the exception of a few appearances by the monster and the repetition of Chapter V when the female creature is made again - to confine itself to the mysteries of the psyche: this exploration focuses primarily on Victor, but also takes into account the analysis of the monster by itself, in the central section devoted to his apology and at the end, during the ultimate encounter with Walton next to Frankenstein's corpse.[22]

The despicable or the sublime emanate, as Saint-Girons notes in his preface to Burke's work, from states of mind most often subject to exhausting existential anguish, linked to isolation, feelings of guilt and also manifestations of the unconscious.[23] The dramatic spring then oscillates between terror and pity (φόβος καὶ ἔλεος), this gothic of the soul returning indeed to the primary sources of the literary movement of the same name, terror, but an internalized terror:[22] each character takes refuge in confession, oral or written (epistolary or narrative), or even, with Walton, in a correspondence that is the vector of the whole story.

The reader is then invited to share the psychological torments that beset him, his sympathy or antipathy is solicited, and a kind of love-hate relationship is established between character and audience.[22] This feeling is based on ambiguity and tension, further accentuated by the distortion (amplification, radicalization, etc.) inflicted on everyone by the narrative structure of a story composed solely of superimposed memory facts.[22]

The quest of modern man

editThis is a step forward in the Gothic movement, which now merges with modern man's quest for identity. This is a confluence with Romanticism, of which the Gothic had previously been no more than a precursor. The terror inflicted, for the reader's pleasure, is that of a rendezvous with a being in a universe belonging to the genre now known as science fiction, where the possible becomes reality and the impossible merely possible. As Brian Wilson Aldriss wrote in 1973 in Billion Year Spree, "science fiction is the quest for the definition of a man and his status in the universe";[24] to this should we add the quest for his integrity.

Imagination and reason

editThe scientific changes, the creative act of Victor Frankenstein, are a matter for the imagination, that faculty of the Romantic artist who has freed himself from the straitjacket of the rules of composition, writing, poetic language and propriety. In the case of the novel, the creative imagination has joined forces with reason to achieve its ambition. This is the logical reason of mathematics and the physical sciences. The alchemist's spark now exists only as enthusiasm; the idealistic quest has been transformed into a methodical quest based on Kant's pure reason. The extraordinary is a matter of order:[25] Victor adds cadaver parts to other parts, essential parts only, since materially, the work remains incomplete; whole patches of skin are missing, the aesthetic aspect has been neglected, even ignored. The successive grafts of disparate elements form a biologically viable but socially inadequate whole, to the extent that its creator is the first to ostracize it. In fact, this logically reasonable approach in the service of the imagination turns out to be a veritable death sentence.[26]

Reason without imagination

editThis reasonable reason lacked imagination. Pure reason in the service of an ambition, however original it may be, as long as it confers power (and here we find again the power evoked by Edmund Burke) must be associated with practical reason, and this is indeed the major originality of the novel, even in its Gothic component: imagination alone does not have all the rights, even when it is based on a logically reasonable approach. The terror that can seize the reader is that of an absence of morality,[27] the morality of personal responsibility[28] (Victor is a kind of father who abandons his child),[29] of social responsibility (he lets loose in the very heart of the city a being whose strength he knows but whose impulses he knows nothing about), morality that is also transcendental,[30] an unrevealed but categorical commandment.[31] Because it was neglected, because it remained a dead letter, because the end had no finality, the dream turns to nightmare, the fairy tale to horror. The hero's transgressive personality becomes villainous:[32] the reader is placed in a world whose equilibrium is disrupted, which collapses and self-destructs; legal institutions explode, the innocent are executed, the falsely guilty are arrested; the very republic is threatened as its leaders, the syndics of the city of Geneva, find themselves destabilized, then annihilated. Even nature seems to express its indignation and wrath: the peaks become menacing, the ice becomes chaotic and frail,[28] boats are seized and then drift away (like people), the peaceful Rhine valley opens onto the lunar, the planet has become hostile, as if subject to evil spells.[33]

A gothic representation of evil

editThe gothic in Frankenstein becomes a representation of the evil that inhabits the human spirit. The novel draws the reader into the hell of a soul that has lived with and served it, despite the good intentions that paved the way. The machinery of frightening strikes at the very depths of being, touching on myth.[34] The terror becomes ontological: to read Frankenstein is to witness first-hand the union of sexuality and death, from baptism to burial. The thrill is to become aware of the human condition; the sublime no longer reaches the heights of the Alps, but the intimate depths of the ego.[35] The necropolises, the mass graves, the workshops of this infamous creation are within each of us, the nooks and crannies of our own dwelling exposed. There's no need for the Gothic vein to seek out unlikely spectres. Even "we", the English, the Christians of whom Henry Tilney speaks, discover, laid bare like the half-covered organs of the monster, the gangrenous shreds of our being.[36]

A demon called love

editThe demon that torments Victor seems to be love, but with it the Map of tender becomes macabre, the plain of desire littered with corpses, right from the seminal dream of the kiss of death.[36] This dream fits in well with the schema of the Gothic nightmare, with its successive metamorphoses, in fact anamorphoses, and at the end of the journey, its maternal corpse, eaten away by worms.[37] It is also the proleptic expression of the internal fatality of which the hero is the victim. Forbidden to express itself, sexuality appears in the darkness of a narrative strewn with clues, signs and symbols. The terror, then, is that which Victor feels for his own love life; the horror is also the horror inspired by the disgust of a couple's accomplishment.[38]

The monster's creation contains within itself Elizabeth's destruction: its creation, then its bringing to life, was the work of a solitary, wifeless man. By killing the young bride, the monster fulfills his creator's secret desire to remain a virgin father. It's a kind of Immaculate Conception for men, an aberration of Eros that turns into Thanatos:[39] "the hue of death" that lingers on Elizabeth's lips is identical to the deathly pallor inhabiting the monster's face. Fear of sex or simply recoil from incestuous desire,[40] the desire is satisfied by proxy: the monster, Victor's negative double, an unavowable part of his ego, does the work.[41] In fact, the conception was indeed stained.[42]

Fantasy and reality

editFrankenstein naturalizes the Gothic supernatural: the unavowable and unformulated imaginary becomes reality, fantasy (or phantasy)[Note 2][42] occupying the entire sphere of the real, with neurosis becoming the very reality of the novel.

In this respect, Frankenstein is similar to works by Rétif de la Bretonne (1734–1806) and Gérard de Nerval (1808–1855), and foreshadows Balzac's La Peau de chagrin (1831), Edgar Poe's Ligeia (1838) and Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).[42] Frankenstein brings the genre to its apogee, but heralds its death with its overly tranquil trajectory: it will have been secularized, rid of the miraculous; its fantastic is explained and, above all, recognized as a constituent part of man; the reader is enclosed within a framework of rationality.[36]

A disguised denunciation of Gothic style

editFrankenstein uses Gothic conventions and discourse only to denounce them.[12] As Max Duperray shows, the novel's setting is, in fact, a " bourgeois rationalist setting."[22]

The characters are often wealthy notables, always refined and enamored of good manners, indulging in the delights of cultural tourism, not prone to rambling, regretting the unorthodox choices of Clerval's studies, too inclined towards orientalism. Likewise, the monster is drawn to belles-lettres and music. For him, books are the very expression of truth: he reads Paradise Lost "as if it were a true story."[43] These enlightened minds, believing in human, individual and social progress, were "inspired, as Robert Walton writes, by a breeze of promise."[44] Although they are convinced that nature is beautiful and good, none of them is fascinated by ignorance and primarity.[45] On the contrary, Victor stands out and distances himself from the simple inhabitants of the Orkney Islands, and the monster prefers to imitate the DeLaceys in their "simple but pretty cottage" rather than the frumpy shepherd whose meal he swallows in the primitive hut. The place where he hides is clearly identified by him as a "hovel" adjoining the pigsty, from which he intends to escape as quickly as possible.[46]

The privileged bourgeois order

editIndeed, it is domestic virtue that this Gothic novel seems to emphasize.[47] The pact it makes is not with the devil, as Faust did,[48] but with the bourgeois order, an order in which excess becomes suspect, haste harmful, and frenzy reprehensible. Frankenstein's eloquence is somewhat undermined by the author's latent irony:[47] his lyrical outbursts are on the margins of comedy, and his heroism almost reaches the heights of the ridiculous. One has the impression that this barely marked passage to the ludicrous ("grotesque ridicule")[Note 3] is like the literary punishment Mary Shelley inflicts on her character.[28] Victor's world is indeed "upside down", as Gabriel Marcel put it:[49] dreams become real existence and, after Elizabeth's death, joy can only be tasted during sleep. The author seems to be warning his reader against the deception of appearances; the monster's actions become a real lesson by example,[28] a lesson in contrast to the consequences of a thoughtless, disruptive, transgressive act.[12]

Frankestein's gothic style is at the service of the law.[50]

Paradoxically realistic gothic

editThe novel, situated under the sign of ambiguity and tension, is therefore paradoxical, just as is a genre that has reached the limits of its expressive possibilities and, with Frankenstein, tips over into the Romantic realm. In fact, insofar as, despite its exaggerations, its linearity, its total lack of verisimilitude, its theoretical substratum and its literary references, this work carves meaning out of human reality, it contains a dose of realism. As Bergson wrote, "Realism is in the work when idealism is in the soul, and [...] it is only by force of ideality that we regain contact with reality."[51] Here, then, the Gothic has revelatory value.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ In her Diary of 1815, Mary Shelley recalls the death of her seven-month-old baby, and has a vision of his return to life through the friction she administers to him.

- ^ "Fantasy" belongs to the conscious; "phantasy" to the unconscious.

- ^ First attested in 1619; from Latin lūdicrus, from lūdō ("to play").

References

edit- ^ a b c Duperray (1994, p. 39)

- ^ a b Duperray (1994, pp. 38–39)

- ^ Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757.

- ^ Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (19 February 1797). Compte rendu de Le Moine de Matthew Gregory Lewis (in French). Critical Review. pp. 194–200.

- ^ Seeber, Barbara Karolina (2000). General consent in Jane Austen : a study of dialogism. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2066-0.

- ^ Austen, Jane. "Northanger Abbey, Chapter 24". fr. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ Horace, Ars Poetica, Ar, translated by C. Lefebvre-Laroche, Paris, P. Didot l'aîné, 1798, c. 188, p. 22.

- ^ Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1827). "On the Supernatural in Literary Composition; and Particularly on the Works of Ernest Theodore William Hoffman" (PDF). Foreign Quarterly Review. 1 (1). Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ "Roman gothique sur L'Encyclopédie Larousse en ligne" (in French). Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Edmund Burke, Recherche philosophique sur l’origine de nos idées du sublime et du beau (In French), B. Saint-Girons (éd), Paris, Vrin, 1990.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 36)

- ^ a b c Levine (1973, p. 17)

- ^ a b Spark, Muriel (1951). Child of Light: A Reassessment of M. W. Shelley. Hadleih: Tower Bridge. p. 74.

- ^ Lecercle, Jean-Jacques (1987). "Fantasme et Phantasme dans Frankenstein de M. Shelley". Études Lawrenciennes (in French) (3): 57–84, 45–46.

- ^ Duperray (1994, pp. 1 and 38)

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 44)

- ^ a b Duperray (1994, p. 46)

- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Du Contrat social ou Principes du droit politique; First book, Chapter VIII (in French).

- ^ Lecercle, Jean-Jacques (1987). "Fantasme et Phantasme dans Frankenstein de M. Shelley". Études Lawrenciennes (in French) (1): 57–84, 93.

- ^ Baldick, Chris (1987). In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 52.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 19)

- ^ a b c d e Duperray (1994, p. 40)

- ^ Saint-Girons, B. (1990). Avant-propos de E. Burke, Recherche philosophique sur l'origine de nos idées du sublime et du beau (in French) (Vrin ed.). Paris: Vrin.

- ^ Aldriss, Brian (1973). Billion year spree: the true history of science fiction. Doubleday. p. 339.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 63)

- ^ Kiely, R. (1972). "Frankenstein". The Romantic Novel in England. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 155–173.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 51)

- ^ a b c d Sanders, Andrew (1996). The short Oxford history of English literature (Revised ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871156-8.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 25)

- ^ Spatt, H. S. (1975). "M. Shelley's Last Men: The Truth of Dreams". Studies in the Novel (7): 526–537.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel; Renaut, Alain (1994). Métaphysique des moeurs. GF. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-070715-4.

- ^ Miyoshi, Masao (1969). The Divided Self. New York: New York University Press. pp. XIV.

- ^ Duperray (1994, pp. 34–35)

- ^ Mill, John M. (1975). "Frankenstein and the Physiognomy of Desire". American Imago. 32 (4): 335–358. eISSN 1085-7931. ISSN 0065-860X. JSTOR 26303110. OCLC 7787910331.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 37)

- ^ a b c Duperray (1994, p. 41)

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 17)

- ^ Floch, Sylvain (1985). "La Chute d'un Ange : le monstrueux à travers le mythe de Shelley et Aldiss". Le Monstrueux (in French) (6). Aix-en-Provence: 137.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 75)

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 67)

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 62)

- ^ a b c Lecercle, Jean-Jacques (1987). "Fantasme et Phantasme dans Frankenstein de M. Shelley". Études Lawrenciennes (3): 57–84, 64.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 20)

- ^ Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, Letter 1 from Roger Walton.

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 72)

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 23)

- ^ a b Duperray (1994, p. 42)

- ^ Duperray (1994, p. 45)

- ^ Quoted by Raymon Aron, Le marxisme de Marx (In French), Le livre de Poche, Éditions de Fallois, 2002, pages 180-181, p. 74-75.

- ^ Levine (1973, p. 30)

- ^ Bergson, Henri (1900). "Chapter III". Le Rire (in French). Paris: PUF. p. 120.

Bibliography

edit- Shelley, Mary; Wolfson, Susan J. (2007). Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus. New York: Pearson Longman. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-321-39953-3.

- Shelley, Mary; Paley, Morton D. (1998). The Last Man. Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-19-283865-0.

- Duperray, Max (1994). Mary Shelley, Frankenstein. Vanves: CNED.

- Ferrieux, Robert (1994). Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (in French). Perpignan: Université de Perpignan Via Domitia. p. 102.

- Hume, Robert D. (1969). "Gothic versus Romantic: A revaluation of the Gothic Novel". PMLA, Modern Language Association. 84 (2): 282–290. doi:10.2307/1261285. JSTOR 1261285.

- Scholes, Robert; Rabkin, Eric S. (1972). Science Fiction: History-Science-Vision. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 182–183.

- Abensour, Liliane; Charras, Françoise (1978). "Gothique au féminin". Romantisme noir (in French). Paris: L'Herne. pp. 244–252.

- Punter, David (1980). "Chapter IV: Gothic and Romanticism". The Literature of Terror: A History of Gothic Fictions from 1765 to th present day. London: Longman.

- Lecercle, Jean-Jacques; et al. (Philosophies) (1994). Frankenstein : mythe et philosophie (in French). Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-041872-4.

- Lacassin, Francis (1991). "Frankenstein ou l'hygiène du macabre". Mythologie du fantastique : les rivages de la nuit (in French). Paris. pp. 29–51. ISBN 9782268012315.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Johanna (1992). Frankenstein, A Case Study in Contemporary Criticism. Boston: Bedford Books of St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312463182.

- Moeckli, Gustave (1962). Une Genevois méconnu : Frankenstein (in French). Genova: Musée de Genève, 111. pp. 10–13.

- Cude, Wilfred. "Mary Shelley's Modern Prometheus: A Study in Ethics of Scientific Creativity" (PDF). The Dalhousie Review. Dalhousie University: 212–225.

- Pollin, Burton R. (1965). "Philosophical and Literary Sources of Frankenstein". Comparative Literature. 17 (2): 97–108. doi:10.2307/1769997. JSTOR 1769997.

- Ketterer, David (1979). Frankenstein's Creation, The Book, The Monster and the Human Reality. Victoria: Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-0920604304.

- Ponneau, G. (1976). Le mythe de Frankenstein et le retour aux images (in French). Paris: Trames. pp. 3–16. Collection: Littérature comparée

- Levine, George (1973). "Frankenstein and the Tradition of Realism". Novel. 7: 14–30.