Grecia was a literary magazine which was published from 1918 to 1920 in Spain. Its subtitle was Revista Decenal de Literatura (Spanish: Decennial Literature Magazine).[1] Later it was redesigned as Revista de literatura (Spanish: Literature Magazine).[2] It was a traditionalist as reflected in its title[3] and modernist publication in the early years, but later adopted an avant-garde approach and became the flagship of the ultraísmo.

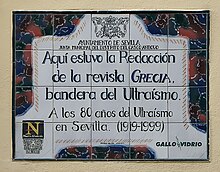

Commemorative plaque in Seville for the 80th anniversary of the ultraísmo manifesto in Grecia | |

| Editor | Rafael Cansinos-Asséns |

|---|---|

| Former editors | Adriano del Valle |

| Categories | Literary magazine |

| Founder | Isaac del Vando Villar |

| Founded | 1918 |

| First issue | 18 October 1918 |

| Final issue | November 1920 |

| Country | Spain |

| Based in | |

| Language | Spanish |

History and profile

editGrecia was established by the Andalusian poet Isaac del Vando Villar in Seville in 1918 as a modernist literary magazine.[4] Its first issue appeared on 18 October 1918.[1] Adriano del Valle was the first editor-in-chief of the magazine which had 24 pages throughout its run.[4]

Although Grecia adhered to modernism, over time it covered the work by writers from distinct literary waves such as futurism, cubism, dadaism and expressionism.[4] The first manifesto of the ultraísmo group was published in the magazine in 1919.[5] The group included Guillermo de Torre, Rafael Cansinos-Asséns, Gerardo Diego and Jorge Luis Borges.[5] Following this incident Grecia became the leading media outlet of the avant-garde in Spain.[6] In addition, it played a significant role in the introduction of the ultraísmo in other Spanish-speaking countries, including Mexico.[5] Pedro Garfias published his poem Domingo (Spanish: Sunday) in the magazine which was a typical example of the ultraist poetry.[3]

The headquarters of Grecia moved to Madrid in the summer of 1920.[1][3] During this period Rafael Cansinos-Asséns edited the magazine. Its title page and header was redesigned by Norah Borges to reflect its avant-garde character.[1][7] The magazine folded in November 1920.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Vanessa K. Davidson (2009). "Norah Borges, the Graphic Voice of Ultraísmo in Two Peripheral Centres". Romance Studies. 27 (1): 13–15, 18. doi:10.1179/174581509X397993.

- ^ José Mª Barrera López, ed. (1998). Grecia: revista de literatura (in Spanish). Málaga: Centro Cultural de la Generación del 27.

- ^ a b c Zachary Rockwell Ludington (2022). "Spanish Ultraism's Sacred Woman of the Future". In Günter Berghaus; Monica Jansen; Luca Somigli (eds.). International Yearbook of Futurism Studies. Vol. 11. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 209–210, 215. doi:10.1515/9783110752380-009. ISBN 978-3-11-075238-0.

- ^ a b c "Grecia (Sevilla)". Hemeroteca Digital (in Spanish). 18 March 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Vanessa Fernandez (2013). A Transatlantic Dialogue: Argentina, Mexico, Spain, and the Literary Magazines that Bridged the Atlantic (1920-1930) (Ph.D. thesis). University of California, Los Angeles. pp. 10, 88.

- ^ Kelly S. Franklin (Summer 2017). "A Translation of Whitman Discovered in the 1912 Spanish Periodical Prometeo". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 35 (1): 120. doi:10.13008/0737-0679.2267.

- ^ Eamon McCarthy (2015). "Flirting with Futurism: Norah Borges and the Avant-garde". In Günter Berghaus (ed.). International Yearbook of Futurism Studies. Vol. 5. Berlin; München; Boston: De Gruyter. p. 116. doi:10.1515/9783110422818-007. ISBN 9783110422818.