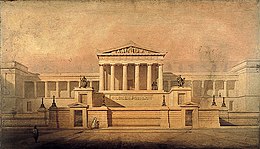

Greek Revival architecture was a style that began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe, the United States, and Canada, as well as in Greece itself following its independence in 1821. It revived many aspects of the forms and styles of ancient Greek architecture, in particular the Greek temple. A product of Hellenism, Greek Revival architecture is looked upon as the last phase in the development of Neoclassical architecture, which was drawn from Roman architecture. The term was first used by Charles Robert Cockerell in a lecture he gave as an architecture professor at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1842.[1]

With newfound access to Greece and Turkey, or initially to the books produced by the few who had visited the sites, archaeologist–architects of the period studied the Doric and Ionic orders. Despite its universality rooted in ancient Greece, the Greek Revival idiom was considered an expression of local nationalism and civic virtue in each country that adopted it, and freedom from the lax detail and frivolity that then characterized the architecture of France and Italy, two countries where the style never really took architecturally. Greek Revival architecture was embraced in Great Britain, Germany, and the United States, where the idiom was regarded as being free from ecclesiastical and aristocratic associations and was appealed to each country's emerging embrace of classical liberalism.

The taste for all things Greek in furniture and interior design, sometimes called Neo-Grec, reached its peak in the beginning of the 19th century when the designs of Thomas Hope influenced a number of decorative styles known variously as Neoclassical, Empire, Russian Empire, and Regency architecture in Great Britain. Greek Revival architecture took a different course in a number of countries, lasting until the 1860s and the American Civil War and later in Scotland.

Modern-day architects are recreating this design by building houses similar to the Greek Revival. These houses are characterized by their symmetrical and balanced proportions, typically featuring a bold, pedimented portico with arched openings. The symmetrical façade is divided into two equal halves.

General characteristics

editMuch Greek Revival architecture used the Greek Doric order in the earlier version found in buildings leading up to the Parthenon in Athens. This contrasted significantly with later Greek Hellenistic architecture and Roman architecture. Greek Doric columns are typically rather thick, often tapering towards the top, always fluted, and have complicated rules for the entablature above the columns. Additionally, the columns go straight down to the floor (stylobate) with no distinct base - this last aspect was often skipped by architects who followed the other Greek conventions, for example in the Brandenburg Gate.

The understanding of actual Greek architecture was based on ruined buildings, and awareness of the full range of ornamentation, and colour, on ancient Greek temples emerged over the period. Architects were aware of the large pedimental sculptures and metope reliefs, and copied these expensive elements when funds allowed, but far less often had the full range of antefixes and akroterions.

Greek temples normally had no windows except perhaps in the roof, posing a problem for modern buildings for most purposes, which was generally brushed aside. Many buildings that needed to fulfill modern functions concentrated on having an impressive temple-style front, giving the other faces of the building a more practical design up to the cornice.

Europe

editGermany and France

editIn Germany, Greek Revival architecture is predominantly found in two centres, Berlin and Munich. In both locales, Doric was the court style rather than a popular movement and was heavily patronised by Frederick William II of Prussia and Ludwig I of Bavaria as the expression of their desires for their respective seats to become the capital of Germany. The earliest Greek building was the Brandenburg Gate (1788–91) by Carl Gotthard Langhans, who modelled it loosely on the Propylaea in Athens. Ten years after the death of Frederick the Great, the Berlin Akademie initiated a competition for a monument to the king that would promote "morality and patriotism."

Friedrich Gilly's unexecuted design for a temple raised above the Leipziger Platz caught the tenor of high idealism that the Germans sought in Greek architecture and was enormously influential on Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Leo von Klenze. Schinkel was in a position to stamp his mark on Berlin after the catastrophe of the French occupation ended in 1813; his work on what is now the Altes Museum, Konzerthaus Berlin, and the Neue Wache transformed that city. Similarly, in Munich von Klenze's Glyptothek and Walhalla memorial were the fulfilment of Gilly's vision of an orderly and moral German world. The purity and seriousness of the style was intended as an assertion of German national values and partly intended as a deliberate riposte to France, where it never really caught on.

By comparison, Greek Revival architecture in France was never popular with either the state or the public. What little there is started with Charles de Wailly's crypt in the church of St Leu-St Gilles (1773–80), and Claude Nicolas Ledoux's Barriere des Bonshommes (1785–89). First-hand evidence of Greek architecture was of very little importance to the French, due to the influence of Marc-Antoine Laugier's doctrines that sought to discern the principles of the Greeks instead of their mere practices. It would take until Labrouste's Neo-Grec of the Second Empire for Greek Revival architecture to flower briefly in France.

Great Britain

editFollowing the travels to Greece, Nicholas Revett, a Suffolk architect, and the better remembered James Stuart in the early 1750s, intellectual curiosity quickly led to a desire among the elite to emulate the style. Stuart was commissioned after his return from Greece by George Lyttelton to produce the first Greek building in England, the garden temple at Hagley Hall (1758–59).[2] A number of British architects in the second half of the century took up the expressive challenge of the Doric from their aristocratic patrons, including Benjamin Henry Latrobe (notably at Hammerwood Park and Ashdown House) and Sir John Soane, but it remained the private enthusiasm of connoisseurs up to the first decade of the 19th century.

An early example of Greek Doric architecture married with a more Palladian interior, is the facade of the Revett-designed rural church of Ayot St Lawrence in Hertfordshire, commissioned in 1775 by Lord Lionel Lyde of the eponymous manor. The Doric columns of this church, with their "pie-crust crimped" details, are taken from drawings that Revett made of the Temple of Apollo on the Cycladic island of Delos, in the collection of books that he (and Stuart in some cases) produced, largely funded by special subscription by the Society of Dilettanti. See more in Terry Friedman's book The Georgian Parish Church, Spire Books, 2004.

Seen in its wider social context, Greek Revival architecture sounded a new note of sobriety and restraint in public buildings in Britain around 1800 as an assertion of nationalism attendant on the Act of Union, the Napoleonic Wars, and the clamour for political reform. William Wilkins's winning design for the public competition for Downing College, Cambridge announced the Greek style was to become a dominant idiom in architecture, especially for public buildings of this sort. Wilkins and Robert Smirke went on to build some of the most important buildings of the era, including the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden (1808–1809), the General Post Office (1824–1829) and the British Museum (1823–1848), the Wilkins Building of University College London (1826–1830), and the National Gallery (1832–1838).

One of the greatest British proponents of the style was Decimus Burton.

In London, twenty three Greek Revival Commissioners' churches were built between 1817 and 1829, the most notable being St.Pancras church by William and Henry William Inwood. In Scotland the style was avidly adopted by William Henry Playfair, Thomas Hamilton and Charles Robert Cockerell, who severally and jointly contributed to the massive expansion of Edinburgh's New Town, including the Calton Hill development and the Moray Estate. Such was the popularity of the Doric in Edinburgh that the city now enjoys a striking visual uniformity, and as such is sometimes whimsically referred to as "the Athens of the North".

Within Regency architecture the style already competed with Gothic Revival and the continuation of the less stringent Palladian and Neoclassical styles of Georgian architecture, the other two remaining more common for houses, both in towns and English country houses. If it is tempting to see the Greek Revival as the expression of Regency authoritarianism, then the changing conditions of life in Britain made Doric the loser of the Battle of the Styles, dramatically symbolized by the selection of Charles Barry's Gothic design for the Palace of Westminster in 1836. Nevertheless, Greek continued to be in favour in Scotland well into the 1870s in the singular figure of Alexander Thomson, known as Greek Thomson.

Greece

editFollowing the Greek War of Independence, Romantic Nationalist ideology encouraged the use of historically Greek architectural styles in place of Ottoman or pan-European ones. Classical architecture was used for secular public buildings, while Byzantine architecture was preferred for churches.

Examples of Greek Revival architecture in Greece include the Old Royal Palace (now the home of the Parliament of Greece), the Academy and University of Athens, the Zappeion, and the National Library of Greece. The most prominent architects in this style were northern Europeans such as Christian and Theophil Hansen and Ernst Ziller and German-trained Greeks such as Stamatios Kleanthis and Panagis Kalkos. Despite the prestige of ancient Greece among Europe's educated elite, most people had minimal direct knowledge of the ancient Greek civilization before the middle of the 18th century. The monuments of Greek antiquity were known chiefly from Pausanias and other literary sources. Visiting Ottoman Greece was difficult and dangerous business prior to the period of stagnation beginning with the Great Turkish War. Few tourists visited Athens during the first half of the 18th century, and none made any significant study of the architectural ruins.[3]

It was not until the expedition to Greece funded by the Society of Dilettanti of 1751 by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett that serious archaeological inquiry began in earnest. Stuart and Revett's findings, published in 1762 (first volume) as The Antiquities of Athens,[4] along with Julien-David Le Roy's Ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce (1758) were the first accurate surveys of ancient Greek architecture.[5]

The rediscovery of the three relatively easily accessible Greek temples at Paestum in Southern Italy created huge interest throughout Europe, and prints by Piranesi and others were widely circulated. The Napoleonic Wars denied access to France and Italy to traditional Grand Tourists, especially from Britain. Aided by close diplomatic relations between Britain and the Porte, British travellers, artists and architects went to Greece and Turkey in ever larger numbers to study ancient Greek monuments and excavate or collect antiquities. The Greek War of Independence ended in 1832; Lord Byron's participation and death during this had brought it additional prominence.

Russia

editThe style was attractive in Russia because they shared the Eastern Orthodox faith with the Greeks. The historic centre of Saint Petersburg was rebuilt by Alexander I of Russia, with many buildings giving the Greek Revival a Russian debut. The Saint Petersburg Bourse on Vasilievsky Island has a temple front with 44 Doric columns. Quarenghi's design for the Manege "mimics a 5th-century BC Athenian temple with a portico of eight Doric columns bearing a pediment and bas reliefs".[6]

Leo von Klenze's expansion of the palace that is now the Hermitage Museum is another example of the style.

Turkey

editDuring the late period of the Ottoman Empire, Greek Revival Architecture had its examples in the empire. The prominent examples are Istanbul Archaeology Museums (1891)

Rest of Europe

editThe style was generally popular in northern Europe, and not in the south (except for Greece itself), at least during the main period. Examples can be found in Poland, Lithuania, and Finland, where the assembly of Greek buildings in Helsinki city centre is particularly notable. At the cultural edges of Europe, in the Swedish region of western Finland, Greek Revival motifs might be grafted on a purely Baroque design, as in the design for Oravais Church by Jacob Rijf, 1792. A Greek Doric order, rendered in the anomalous form of pilasters, contrasts with the hipped roof and boldly scaled cupola and lantern, of wholly traditional Baroque inspiration.

In Austria, one of the best examples of this style is the Parliament Building designed by Theophil Hansen.

North America

editCanada

editIn Canada, Montreal architect John Ostell designed a number of prominent Greek Revival buildings, including the first building on the McGill University campus and Montreal's original Custom House, now part of the Pointe-à-Callière Museum. The Toronto Street Post Office, completed in 1853, is another Canadian example.

United States

editWhile some 18th-century Americans had feared Greek democracy, sometimes called mobocracy, the appeal of ancient Greece rose in the 19th century along with the growing acceptance of democracy. This made Greek architecture suddenly more attractive in both the North and the South, for differing ideological purposes: for the North, Greek architecture symbolized the freedom of the Greeks; in the South it symbolized the cultural glories enabled by a slave society.[7] Thomas Jefferson owned a copy of the first volume of The Antiquities of Athens.[8] He never practiced in the style, but he played an important role in introducing Greek Revival architecture to the United States.

In 1803, Thomas Jefferson appointed Benjamin Henry Latrobe as surveyor of public building, and Latrobe designed a number of important public buildings in Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia, including work on the United States Capitol and the Bank of Pennsylvania.[9]

Latrobe's design for the U.S. Capitol was an imaginative interpretation of the classical orders not constrained by historical precedent, incorporating American motifs such as corncobs and tobacco leaves. This idiosyncratic approach became typical of the American attitude to Greek detailing. His overall plan for the Capitol did not survive, though many of his interiors did. He also did notable work on the Supreme Court interior (1806–1807), and his masterpiece was the Basilica of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Baltimore (1805–1821).

Latrobe claimed, "I am a bigoted Greek in the condemnation of the Roman architecture", but he did not rigidly impose Greek forms. "Our religion," he said, "requires a church wholly different from the temple, our legislative assemblies and our courts of justice, buildings of entirely different principles from their basilicas; and our amusements could not possibly be performed in their theatres or amphitheatres."[10] His circle of junior colleagues became an informal school of Greek revivalists, and his influence shaped the next generation of American architects.

Greek revival architecture in the United States also included attention to interior decoration. The role of American women was critical for introducing a wholistic style of Greek-inspired design to American interiors. Innovations such as the Greek-inspired "sofa" and the "klismos chair" allowed both American women and men to pose as Greeks in their homes, and also in the numerous portraits of the period that show them lounging in Greek-inspired furniture.[11]

The second phase in American Greek Revival saw the pupils of Latrobe create a monumental national style under the patronage of banker and philhellene Nicholas Biddle, including such works as the Second Bank of the United States by William Strickland (1824), Biddle's home "Andalusia" by Thomas U. Walter (1835–1836), and Girard College, also by Walter (1833–1847). New York saw the construction (1833) of the row of Greek temples at Sailors' Snug Harbor on Staten Island. These had varied functions within a home for retired sailors.

From 1820 to 1850, the Greek Revival style dominated the United States, such as the Benjamin F. Clough House in Waltham, Massachusetts. It could also be found as far west as Springfield, Illinois. Examples of vernacular Greek Revival continued to be built even farther west, such as in Charles City, Iowa.[12]

This style was very popular in the south of the US, where the Palladian colonnade was already popular in façades, and many mansions and houses were built for the merchants and rich plantation owners; Millford Plantation is regarded as one of the finest Greek Revival residential examples in the country.[13]

Other notable American architects to use Greek Revival designs included Latrobe's student Robert Mills, who designed the Monumental Church and the Washington Monument, as well as George Hadfield and Gabriel Manigault.[9]

At the same time, the popular appetite for the Greek was sustained by architectural pattern books, the most important of which was Asher Benjamin's The Practical House Carpenter (1830). This guide helped create the proliferation of Greek homes seen especially in northern New York State and in Connecticut's former Western Reserve in northeastern Ohio.

Polychromy

editThe discovery that the Greeks had painted their temples influenced the later development of the style. The archaeological dig at Aegina and Bassae in 1811–1812 by Cockerell, Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, and Karl Haller von Hallerstein had disinterred painted fragments of masonry daubed with impermanent colours. This revelation was a direct contradiction of Winckelmann's notion of the Greek temple as timeless, fixed, and pure in its whiteness.

In 1823, Samuel Angell discovered the coloured metopes of Temple C at Selinunte, Sicily and published them in 1826. The French architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff witnessed the exhibition of Angell's find and endeavoured to excavate Temple B at Selinus. His imaginative reconstructions of this temple were exhibited in Rome and Paris in 1824 and he went on to publish these as Architecture polychrome chez les Grecs (1830) and later in Restitution du Temple d'Empedocle a Selinote (1851). The controversy was to inspire von Klenze's "Aegina" room at the Munich Glyptothek of 1830, the first of his many speculative reconstructions of Greek colour.

Hittorff lectured in Paris in 1829–1830 that Greek temples had originally been painted ochre yellow, with the moulding and sculptural details in red, blue, green and gold. While this may or may not have been the case with older wooden or plain stone temples, it was definitely not the case with the more luxurious marble temples, where colour was used sparingly to accentuate architectural highlights.

Henri Labrouste also proposed a reconstruction of the temples at Paestum to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1829, decked out in startling colour, inverting the accepted chronology of the three Doric temples, thereby implying that the development of the Greek orders did not increase in formal complexity over time, i.e., the evolution from Doric to Corinthian was not inexorable. Both events were to cause a minor scandal. The emerging understanding that Greek art was subject to changing forces of environment and culture was a direct assault on the architectural rationalism of the day.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ J. Turner (ed.), Encyclopedia of American art before 1914, New York, p. 198..

- ^ But Giles Worsley detects the first Grecian-influenced architectural element in the windows of Nuneham Park from 1756; see Giles Worsley, "The First Greek Revival Architecture", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 127, No. 985 (April 1985), pp. 226–229.

- ^ Crook 1972, pp. 1–6

- ^ "The Antiquities of Athens", British Museum

- ^ Crook 1972, pp. 13–18.

- ^ FitzLyon, K.; Zinovieff, K.; Hughes, J. (2003). The Companion Guide to St Petersburg. Companion Guides. p. 78. ISBN 9781900639408. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ Caroline Winterer, The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1920 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002, pp. 44–98.

- ^ Hamlin 1944, p. 339

- ^ a b Federal Writers' Project (1937), Washington, City and Capital: Federal Writers' Project, Works Progress Administration / United States Government Printing Office, p. 126.

- ^ The Journal of Latrobe, quoted in Hamlin, Greek Revival d1944), p. 36 (Dover Edition).

- ^ Caroline Winterer, The Mirror of Antiquity: American Women and the Classical Tradition, 1780–1900 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), pp. 102–41

- ^ Gebhard & Mansheim, Buildings of Iowa, Oxford University Press, New York, 1993 p. 362.

- ^ Jenrette, Richard Hampton (2005). Adventures with Old Houses, p. 179. Wyrick & Company.

References

editPrimary sources

edit- Jacob Spon, Voyage d'Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grèce et du Levant, 1678

- George Wheler, Journey into Greece, 1682

- Richard Pococke, A Description of the East and Some Other Countries, 1743–5

- R. Dalton, Antiquities and Views in Greece and Egypt, 1751

- Comte de Caylus, Recueil d'antiquités, 1752–67

- Marc-Antoine Laugier Essai sur l'architecture, 1753

- J. J. Winkelmann, Gedanken uber die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst, 1755

- J. D. LeRoy, Les Ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, 1758

- James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The Antiquities of Athens, 1762–1816

- J. J. Winkelmann, Anmerkungen uber die Baukunst der alten Tempel zu Girgenti in Sicilien, 1762

- J. J. Winkelmann, Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums, 1764

- Thomas Major, The ruins of Paestum, 1768

- Stephen Riou, The Grecian Orders, 1768

- R. Chandler et al., Ionian Antiquities, 1768–1881

- G. B. Piranesi, Differentes vues...de Pesto, 1778

- J. J. Barthelemy, Voyage du jeune Anarcharsis en Grèce dans le milieu du quatrième siecle avant l'ère vulgaire, 1787

- William Wilkins, The Antiquities of Magna Grecia, 1807

- Leo von Klenze, Der Tempel des olympischen Jupiter zu Agrigent, 1821

- S Agnell and T. Evens, Sculptured Metopes Discovered among the ruins of Selinus, 1823

- Peter Oluf Brøndsted, Voyages et recherches dans le Grèce, 1826–1830

- Otto Magnus Stackelberg, Der Apollotempel zu Bassae in Arcadien, 1826

- J. I. Hittorff and L. von Zanth, Architecture antique de la sicile, 1827

- C. R. Cockerell et al., Antiquities of Athens and other places of Greece, Sicily, etc., 1830

- A. Blouet, Expedition scientifique de Moree, 1831–8

- F. Kugler, Uber die Polychromie der griechischen Architektur und Skulptur und ihr Grenze, 1835

- C. R. Cockerell, The Temples of Jupiter Panhellenius at Aegina and of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae, 1860

Architectural Pattern Books

edit- Asher Benjamin, The American Builder's Companion, 1806

- Asher Benjamin, The Builder's Guide, 1839

- Asher Benjamin, The Practical House Carpenter, 1830

- Owen Biddle, The Young Carpenter's Assistant, 1805

- William Brown, The Carpenter's Assistant, 1848

- Minard Lafever, The Young Builder's General Instructor, 1829

- Minard Lafever, The Beauties of Modern Architecture, 1833

- Thomas U. Walter, Two Hundred Designs for Cottages and Villas, 1846.

Secondary sources

edit- Winterer, Caroline. The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1910 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002)

- Winterer, Caroline. The Mirror of Antiquity: American Women and the Classical Tradition, 1780–1900 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007)

- Crook, Joseph Mordaunt (1972), The Greek Revival: Neo-Classical Attitudes in British Architecture 1760–1870, John Murray, ISBN 0-7195-2724-4

- Hamlin, Talbot (1944), Greek Revival Architecture in America, Ohio University Press

- Kennedy, Roger G. (1989), Greek Revival America

- Wiebenson, Dora (1969), The Sources of Greek Revival Architecture

- Hoecker, Christopher (1997), "Greek Revival America? Reflections on uses and functions of antique architectural patterns in American architecture between 1760–1860", Hephaistos — New approaches in Classical Archaeology and related fields, vol. 15, pp. 197–241

- Ruffner, Clifford H. Jr. (1939), Study of Greek Revival Architecture in the Seneca and Cayuga Lake Regions – via Cornell eCommons

- Tyler, Norman; Tyler, Ilene R. (2014). Greek Revival in America: Tracing its architectural roots to ancient Athens. Ann Arbor: Tyler Topics. ISBN 9781503149984. Archived from the original on Aug 4, 2016.