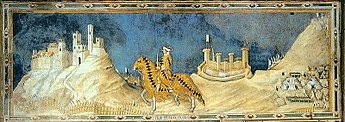

Guidoriccio da Fogliano at the Siege of Montemassi (Italian: Guidoriccio da Fogliano all'assedio di Monte Massi) is a fresco on the western wall of the Sala del Mappamondo in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. It shows Guidoriccio da Fogliano, the commander of the Sienese troops, on horseback against the background of a landscape in which the siege of Montemassi takes place..

| Guidoriccio da Fogliano at the Siege of Montemassi (Guidoriccio da Fogliano all'assedio di Monte Massi) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | traditionally attributed to Simone Martini |

| Year | 1330 (?) |

| Medium | fresco |

| Dimensions | 340 cm × 968 cm (130 in × 381 in) |

| Location | Palazzo Publico, Siena |

For a long time it was assumed that the work was painted in 1330 by Simone Martini. This dating made it one of the first secular portraits and one of the first monumental landscape paintings. It is widely considered a masterpiece of European painting.

In 1977, a frequently acrimonious debate started among art historians about the question whether Martini was indeed the artist. On the same wall in the Sala del Mappamondo another fresco has been discovered that could support the theory that the fresco is not as old as originally thought, and not a work by Martini. However, this matter is still unresolved.

Description

editIn the middle of the fresco Guidoriccio da Fogliano, a condottiero (mercenary officer) and commander of the Sienese troops, is depicted on horseback. He is shown in profile with a Field Marshal’s baton in his hand. On the left Montemassi can be seen surrounded by ramparts. To the right of the central figure of Guidoriccio there is a siege engine with the flag of the Sienese Republic in top. Further to the right there is a group of tents at the foot of a hill, with white and black flags and pennants flying. At the bottom of the fresco the year of the conquest of Montemassi by Sienese troops (1328) is given in Roman numerals: MCCC.XX.VIII.

History

editThe murals in the Palazzo Pubblico were commissioned by the Council of Nine, Siena's ruling body. The murals capture important triumphs in the history of Siena. From the beginning of the 14th century the city council commissioned murals of castles and cities that were conquered by Siena. By decorating the meeting room of the Council of Nine with these images, it was made clear that these cities and castles were now the inalienable property of Siena. In this sense, the frescoes can be seen as an artistic form of political propaganda.[1]

These frescoes eventually filled two walls of the meeting room in the Palazzo Pubblico. Between 1314 and 1331 at least seven castles were painted. Documents show that Simone Martini painted at least four of them: Montemassi and Sasso Forte in 1330, and Arcidosso and Castel Del Piano in 1331.[2] Around 1345, many of these frescoes had to make way for the Mappamondo, the world map by Ambrogio Lorenzetti which is now lost. In the seventeenth or eighteenth century, major restoration work was carried out to restore images that had been lost during the construction of the Mappamondo.[1]

The fresco with the equestrian image has always captured the imagination of art historians and the general public. It is seen as a unique mix of realism and artistic imagination. For many it is not just a portrait of one particular warlord during a specific campaign, but a reflection on war and knighthood in general. The Guidoriccio has been considered one of the first secular, i.e. strictly non-religious, portraits, and one of the first monumental landscape paintings in Western art.[1] An icon of 14th-century art, it was considered to be one of the best works by Simone Martini.

Over the centuries, the horseman has become an emblem of Siena which is still frequently found on souvenirs and local products. Many tourists came, and come, to Siena to see the fresco.[2]

Controversy

editThe Castle of Montemassi is clearly recognizable in the Guidoriccio. Therefore, it was long believed that this must be the fresco that Simone Martine was commissioned to paint by the Sienese city government in 1330. This assumption was challenged in 1977 by the American art historians Gordon Moran and Michael Mallory. At first, they claimed that while most of the fresco had indeed been painted by Martini, the central image of the horseman had not. They came to this conclusion because in their view horse and rider are not really part of the wider scene. They also pointed out that commander Guidoriccio da Fogliano changed his allegiance to on an enemy of Siena in 1333. It seemed unlikely that the Council of Nine would have tolerated the portrait of "a turncoat" in such a prominent place in the town hall. Moran and Mallory suggested that the rider image was added to the fresco in 1351, after the death of Guidoriccio da Fogliano who had by then been reinstated as commander of the Sienese troops. Simone Martini died in 1344.[3][2]

This theory was at first not taken seriously at all, and later fiercely contested. Moran and Mallory have stated that they were systematically thwarted by prominent Italian art historians and by the Sienese authorities. Their publications were rejected by journals and not included in scholarly bibliographies and catalogs. They say that they were prevented from presenting their theory at conferences, and were not allowed to do further research in Siena.[2]

New ideas on attribution

editThe debate took on a new dimension a few years later when a previously unknown fresco was discovered on the western wall of the Sala del Mappamondo. It is probably one of the castle frescoes that disappeared behind plaster circa 1345 when the Mappamondo was installed in the hall. It is partly overlapped by the Guidoriccio, has a similar theme (two persons and a castle) and is of high quality. Some point to Duccio as the creator, others argue that this underlying fresco is definitely by Simone Martini. According to Moran and Mallory, this is Martini's fresco of the castle in Arcidosso. This would mean that the Guidoriccio cannot be the Montemassi fresco painted by Simone Martini in 1330 because it partly overlaps the image of Arcidosso, which was painted a year later in 1331.

The main issue in the Guidoriccio debate therefore no longer was whether perhaps the equestrian image had not been painted by Simone Martini, but whether the entire fresco could be attributed to him. It has been suggested that the Guidoriccio was painted by Lippo Memmi, a brother-in-law of Simone Martini who had a similar style. However, this theory is not widely supported.[2][3]

New ideas about dating

editThe debate on the correct attribution of the Guidoriccio raged for decades in scientific journals as well as in the wider media; still no final conclusion has been reached. It is unusual for a debate among art historians about the dating and attribution of a 14th-century work of art to take this long and get so much public attention. Those who think that it is a work by Simone Martini base their opinion on stylistic similarities with his other work. Their opponents point out facts concerning the technical preparation of the fresco and possible anachronisms in the imagery that would make it unlikely that it was painted around 1330.[3] They refer to the architecture of the castles, heraldic elements and the siege engines depicted. They usually conclude that the Guidoriccio could not have been painted before the fifteenth century. The fact that Vasari in his famous painters' biography Le Vite from 1550 makes no mention of a work as prominent as the horseman fresco is seen by some as a reason to date it even later.[2] There is still no consensus about the painter and the date of creation of the Guidoriccio.

References

edit- ^ a b c Kempers, Bram (1987). Kunst, macht en mecenaat (Painting, Power and Patronage: The Rise of the Professional Artist in the Italian Renaissance). ISBN 9029525207.

- ^ a b c d e f Moran, Gordon (1991). "The Guido Riccio controversy and resistance to critical thinking". Syracuse Scholar. 11.

- ^ a b c De Wesselow, Thomas (2004). "The Guidoriccio fresco: a new attribution:". The Free Library.