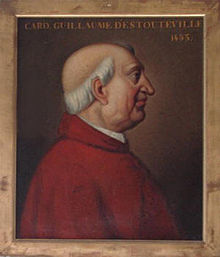

Guillaume d'Estouteville (c. 1412–1483) was a French aristocrat of royal blood who became a leading bishop and cardinal. He held a number of Church offices simultaneously. He conducted the reexamination of the case of Jeanne d'Arc and exonerated her of the charges against her. He reformed the Statutes of the University of Paris. In Rome he became one of the most influential members of the Curia, as the official Protector of France in church business. Pope Sixtus IV appointed him Chamberlain of the Holy Roman Church (Camerlengo). His great wealth allowed him to be a generous patron of the arts, especially in the building and adornment of churches.

Guillaume d'Estouteville | |

|---|---|

| Cardinal, Archbishop of Rouen | |

| |

| Church | Roman Catholic |

| Archdiocese | Rouen |

| In office | 1453–1483 |

| Other post(s) | Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia e Velletri (1461–83) Cardinal-Priest of Santa Pudenziana (1459–83) Bishop of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne (1453–83) |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 10 January 1440 |

| Created cardinal | 18 December 1439 by Pope Eugene IV |

| Rank | Cardinal-Bishop |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1412 |

| Died | 22 January 1483 Rome, Papal States |

| Buried | Sant'Agostino, Rome |

| Nationality | French |

| Parents | Jean d'Estouteville, Sieur de Vallemont Marguerite d'Harcourt |

| Partner | Girolama Togli |

| Children | 5 |

| Occupation | diplomat, courtier |

| Education | Master of Arts, Canon Law |

done shortly after his death by Mino da Fiesole, Metropolitan Museum, New York City

Life

editD'Estouteville was born c. 1412[1] in either Valmont or Estouteville-Écalles in the Duchy of Normandy, a member of the most powerful family in the region. His father, Jean d'Estouteville, Sieur de Vallemont and Grand Chamberlain of France, had fought at Agincourt, was captured, and spent twenty years as a prisoner of war.[2] His mother was Marguerite d'Harcourt, the daughter of Catherine de Bourbon, the sister of Jeanne de Bourbon who was the wife[3] of King Charles V of France.[4] Guillaume had an elder brother Louis, who became Grand Bouteiller of France.[5] As the custom was, the younger brother was destined for a career in the Church. The family lost a great deal of property and income as a result of the English occupation of Normandy after the Battle of Agincourt.[6] A collateral ancestor (uncle?),[7] also called Guillaume d'Estouteville, had been Bishop of Évreux (1375–1376) at the age of twenty, Bishop of Auxerre (1376–1382), and Bishop of Lisieux (1382–1415).[8]

It was first said by Alfonso Chacón,[9] and often repeated thereafter, that Guillaume became a Benedictine monk at the Saint-Martin-des-Champs Priory in Paris, where he soon became prior.[10] Both of these statements, however, have been shown to be mistaken. Documentary evidence written at Saint-Martin in 1500 shows that he was a secular priest, and that he was Administrator of Saint-Martin.[11] Chacon also states that d'Estouteville was Doctor Decretorum (Doctor of Canon Law), but various papal documents of Pope Eugenius IV, in particular one of 1435, call him a Papal Notary, a relative of the Kings of France, a Master of Arts, and of Canon Law, as a result of having passed rigorous examinations.[12] Henri Denifle states that d'Estouteville's degree in Canon Law did not come from the University of Paris.[13] Guillaume did possess a Canonry in the Church of Évreux, and in 1432 he was Canon in Lyon as well. In 1433 he became Canon in Angers.

He later became commendatory abbot simultaneously of the Abbeys of Mont Saint-Michel (1444–1483), of Saint-Ouen at Rouen and of Montebourg.

Bishop

editThe Bishop of Angers, Hardouin du Brueil, died on 18 January 1439.[14] Guillaume D'Estouteville, who was ambitious for the post, immediately rushed to Rome and obtained bulls from Pope Eugene IV on 20 February[15] naming him to the bishopric. On 28 February the Canons of the Cathedral Chapter met and duly elected Jean Michel of Beauvais, a Councillor of Rene of Anjou and Canon of Rouen and of Angers, though d'Estouteville received several votes in the election. The election of Jean Michel was confirmed by the Vicars-General of the Archbishop of Tours. The bulls which d'Estouteville had obtained in Rome were presented to the Chapter of Angers on 24 April by d'Estouteville's procurator, but the majority of the Chapter rejected his bid. In the meantime Bishop Jean Michel was sitting as Bishop of Angers in the Council of Basel. King Charles VII of France was angered at the interference of the Pope in French church affairs and threatened, in support of the Gallican church, to apply the Pragmatic Sanction and exclude the Pope's bulls.[16] Pope Eugene escaped from the danger by giving d'Estouteville the bishopric of Digne in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, a suffragan of Embrun.[17] He renounced his claim on Angers on 27 October 1447.[18]

On 18 April 1440, he was named the Apostolic Administrator of the Diocese of Mirepoix; his commission was revoked upon the appointment of a new bishop on 17 May 1441. He never visited Mirepoix, but he did collect a year's income.[19]

Cardinal

editA few months after the affair of Angers, Guillaume d'Estouteville was named a cardinal priest in the consistory of 18 December 1439 by Pope Eugene IV,[20] and assigned the titular church of San Martino ai Monti. The Cardinal's hat probably softened the disappointment of losing the bishopric of Angers. Pope Eugene probably derived a bit of satisfaction at granting a red hat to a member of the French royalty without the request or consent of the King.

He was consecrated a bishop in January 1440. In 1440 he was briefly administrator of the diocese of Conserans (St. Lizier)[21] The following year he was additionally appointed Administrator of the Dioceses of Béziers and Nîmes.[22]

In 1443, Cardinal d'Estouteville was appointed Archpriest of the Basilica Liberiana (Santa Maria Maggiore) by Pope Eugene IV,[23] in succession to Cardinal Niccolò Albergati, who had died on 9 May 1443.[24] He held the position for life. In March 1451 Pope Nicholas V granted a new set of Statutes to the Canons of the Basilica, which emphasized the decisive power that the Archpriest had over the physical structure of the church and its property.[23] In his Testament d'Estouteville left funds for the refurbishment and redecoration of the Chapel of S. Michele e S. Pietro in Vincoli, and for the building of the Chapel of S. Antonio.[25]

On 7 January 1450 D'Estouteville was appointed Administrator of the Diocese of Lodève.[26] He served in this office for three years, before being appointed bishop of the Diocese of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in Savoy. He was Bishop of Maurienne from 26 January 1453 to 20 April 1453, though he continued to act as Administrator of the diocese for the rest of his life.[27] In April 1453 he was released from his obligation as Bishop of Maurienne and appointed Archbishop of Rouen by Nicholas V.[28] The Canons of Rouen protested the violation of their rights, and Pope Nicholas granted them an Indult on 16 November promising them that, on the death of Guillaume d'Estouteville, they could elect whomever they wished. D'Estouteville took possession of the diocese of Rouen on 30 April 1453 through a Procurator, Bishop Louis d'Harcourt of Narbonne.[29]

Diplomat

editOn 13 August 1451 Cardinal d'Estouteville was sent to France as legate by Pope Nicholas V, at the instigation of the Duc de Bourbon, to make peace between King Charles VII of France and England;[30] at the same time Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa was sent to England on the same mission. Both failed.[31]

At the behest of the Inquisitor General Jean Brehal, Estouteville undertook an ex officio revision of the trial of Joan of Arc. He afterwards reformed the statutes of the University of Paris, issuing his decree on 1 June 1452. He shortened the course leading to the Doctorate in theology from fifteen to fourteen years, and he removed the requirement that Doctors of Medicine be in holy orders.[32] He then presided over the Assembly of the French clergy which met at Bourges in July and August 1452 to discuss the implementation of the Pragmatic Sanction.[33] He finally returned to Rome on 3 January 1453,[34] where he passed almost all the rest of his life.[30]

D'Estouteville, appointed Legate to the King of France, set out from Rome for France on 16 May 1454, with permission to be outside the Curia for six months; he returned to Rome on 12 September 1455 after sixteen months absence.[35] His official mission was to attempt to persuade Charles VII to join in yet another crusade, the one that Nicholas V had tried to launch on 30 September 1453, following the Fall of Constantinople.

Rome

editOn his return, he built as his residence the Palazzo Apollinare to the west of the Church of S. Agostino and adjacent to the Church of S. Apollinare.[36]

Conclaves

editD'Estouteville participated in the papal conclave of 4–10 March 1447[37] that elected Pope Nicholas V.[38] He was absent from Rome, however, during the sede vacante of 24 March–8 April 1455, prior to the election of Pope Calixtus III.[39] On 20 February 1456 he was one of the cardinals who subscribed the bull of Pope Calixtus III which created Rodrigo Borgia a cardinal.[40]

D'Estouteville took part in the Conclave of 6–19 August 1458[41] and was a candidate for the papacy in the Conclave. He was able to command six votes out of the nineteen participants, but he was defeated by Cardinal Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini of Siena, who chose the name Pope Pius II.[42]

In 1458 Cardinal d'Estouteville was asked by the Teutonic Knights to be their Protector at the Roman Curia, an honor and office which he accepted.[43] D'Estouteville also was cardinal protector of the Augustinian Hermits. In January 1459 he accompanied Pope Pius II in his journey to Mantua to meet with the princes of Europe to arrange for a crusade against the Ottoman Turks.[44]

He became Cardinal Bishop of Porto-Santa Rufina on 19 March 1459.[45] He was named the Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia on 26 October 1461, and became the Dean of the College of Cardinals after the death of Cardinal Bessarion on 18 November 1472.[46]

He took part in the Conclave of 27/28–30 August 1464,[47] in which Pope Paul II (Pietro Barbo of Venice) was elected in the first Scrutiny.[48]

On 11 January 1468 the Cardinal was elected Chamberlain of the College of Cardinals for a one-year term. This was a burdensome office, requiring the holder to see to it that monies due to the College of Cardinals from all sources, including the Pope, were collected, and to see to it that they were disbursed to the cardinals who were in the Roman Curia.[49]

Campaign for the Papacy

editPope Paul died on 26 July 1471, and Cardinal d'Estouteville immediately began campaigning openly for the papacy. He wrote to Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, seeking his support and that of the four cardinals who were 'Friends of the Prince'. But there were other candidates, notably Cardinal Bessarion, who was being supported by Venice. Eighteen cardinals, out of the twenty-five living cardinals, attended the Conclave, which began on 6 August 1471.[50] In the second Scrutiny, on 9 August, Cardinal Francesco della Rovere was elected with thirteen of the eighteen votes. D'Estouteville had received six votes. Della Rovere chose as his papal name Sixtus IV.

On 25 August 1471, Cardinal d'Estouteville, availing himself of the traditional privilege of the Bishops of Ostia, consecrated Cardinal Francesco della Rovere, O.F.M.Conv., who had been elected Pope Sixtus IV, a bishop.[51] The Coronation took place on the same day on the front steps of the Vatican Basilica by Cardinal Rodrigo Borja, the senior Cardinal Deacon.[52]

The Cardinal also owed a vineyard near the Porta S. Maria del Popolo. On 15 May 1472 he gave a luncheon there in honor of Cardinal Rodrigo de Borja, who was leaving Rome on a mission to Catalonia and Spain.[53] Earlier that day, the seals of the Chamberlain of the Sacred College were transferred from Cardinal Borjia, who was Chamberlain for the year, to Cardinal d'Estouteville, who was to fill out the rest of his term.[54] On 12 October 1472, he was appointed in Consistory to be Legate in France.[55]

He was appointed Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church (S.R.E. Camerarius)[56] by Pope Sixtus IV in 1477, in succession to Cardinal Latino Orsini, who had died on 11 August 1477. D'Estouteville held the position until his death; he was the last non-Italian cardinal to hold the office for nearly five hundred years, until Jean-Marie Villot in 1970.

Patron of the Arts

editRouen (the episcopal palace), Mont Saint-Michel (the choir of the church), Pontoise (the episcopal palace), and the Château de Gaillon[57] owe the construction of many buildings to his initiative. In his capacity as Bishop of Ostia d'Estouteville had the walls of the town restored, and built the Cathedral of Saint Aurea. In Velletri he rebuilt the episcopal palace.[58] The cardinal also financed the rebuilding of the Church of St. Agostino in Rome.[59] He then had the remains of Saint Monica, the mother of St. Augustine, brought from Ostia Antica for entombment in a marble sarcophagus he had built for them. His name prominently embellishes the façade.[60] He is also credited with building the Church of S. Agostino at Cori and the Church of S. Agostino at Tolentino.[61] He was a generous donor of sacred articles to the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi in March 1482.[62]

D'Estouteville died in Rome on 22 January 1483.[22] His remains were buried in the Basilica of Sant'Agostino. His heart, however, was removed, as was the custom, and taken to be placed in the tomb he had built for himself in the Cathedral of Rouen.[63] A bust of him was placed at the entrance to the sacristy of S. Agostino, with an inscription dated 1865.[64]

Family

editWith his mistress, Girolama Togli, Guillaume d'Estouteville had five children, including Girolamo Tuttavilla (Tuttavilla is an Italian version of Estouteville),[65] a son Agostino,[66] a daughter Margherita,[67] and a daughter Giulia.[68]

Works

editEpiscopal Succession

editCardinal d'Estouteville performed a number of episcopal consecrations in Rome as part of his duties in the Roman Curia. He has the distinction of being the origin of the oldest extant, traceable episcopal lineage within the Catholic Church and the most numerous non-Rebiban lineage.[69] This refers to the ongoing effort to trace the links from one bishop to his consecrator, to his consecrator, etc., all the way back to the Apostles. Thus far, the research has only been able to establish connections back to the mid-fifteenth century.

In the case of d'Estouteville, he consecrated Pope Sixtus IV; therefore, all bishops consecrated by Sixtus IV are in the "d'Estouteville Line". Sixtus IV consecrated Pope Julius II, and thus all bishops consecrated by Julius II are in the "d'Estouteville Line". Julius II consecrated Raffaele Riario, who consecrated Pope Leo X, and therefore all bishops consecrated by Leo X are in the "d'Estouteville Line". The major problem is that there is no evidence as to who consecrated d'Estouteville himself. The fact that there is a "d'Estouteville Line", therefore, is an accident of missing information.

While bishop, he was the principal consecrator of:[22]

- Amauri d'Acigné, Bishop of Nantes (1462);

- Garsias de La Mothe, Bishop of Oloron (1465);

- Giacopo Antonio Venier, Bishop of Siracusa (1465);

- Antonio Alamandi, Bishop of Cahors (1466);

- Brande Castiglioni, Bishop of Como (1466); and

- Francesco della Rovere, (Pope Sixtus IV) (1471).

References

edit- ^ Esposito, Anna (1993). Estouteville, Guillaume d', Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 43. Retrieved: 2016-11-25.

- ^ Nicholas Harris Nicolas (1832). History of the Battle of Agincourt, and of the Expedition of Henry the Fifth Into France in 1415 (second ed.). London: Johnson & Company. pp. Appendix, pp. 24–28.

- ^ Denifle (1897), p. xxii. The Cardinal's arms were supercharged with a shield portraying the Arms of France differenced by a gold band (Bourbon, in honor of his grandmother). Barbier de Montault, p. 22. See: Gill (1996), p. 501, fig. 3, where the arms of d'Estouteville are quartered with those of Haricourt, with the arms of Bourbon superimposed; this stemma was placed on the central boss of the chapel vault by the Cardinal in his lifetime.

- ^ Mollier, p. 3.

- ^ Gallia christiana, XI, p. 90.

- ^ Henri Denifle collected materials bearing on the destruction suffered by monasteries and churches because of the English. Henri Denifle (1897). La désolation des églises, monastères, hopitaux en France, pendant la guerre de cent ans (in French and Latin). Vol. Tome I. Paris: A. Picard et fils. pp. 66–90.

- ^ Anselme de Sainte-Marie; Ange de Sainte-Rosalie (1733). Histoire de la Maison Royale de France, et des grands officiers de la Couronne (in French). Vol. Tome septième (7) (troisième ed.). Paris: Compagnie des libraires associés. pp. 90–91. cf. p. 96.

- ^ Eubel, I, pp. 120, 234, 304. H. Fisquet, La France pontificale: Metropole de Rouen: Evreux (Paris: E. Repos 1864), pp. 36-37.

- ^ Ciaconius, Alphonsus (Alfonso Chacon) (1677). Vitae et res gestae Pontificum romanorum et S.R.E. Cardinalium: ab initio nascentis ecclesiae vsque ad Clementem IX P.O.M (in Latin). Vol. Tomus secundus. Roma: cura et sumptib. Philippi et Ant. De Rubeis. pp. 913–915. He was misled by an inscription of 1637 placed as a memorial in the church of S. Agostino by Benedictine monks, of whose Order d'Estouteville had been Protector. See Barbier de Montault, p. 7 note 13.

- ^ He actually became Prior Commendatarius in 1471. Denifle, p. xxii.

- ^ Denifle (1897), xx-xxi: monasterium Sancti Martini per spatium centum annorum et amplius per seculares rectum fuerat, administratum et gubernatum, videlicet per dominos cardinals Laudunensem, Rothomagensem, Lugdunensem, patriarchum Antiochenum, et episcopum Nannetensem..."

- ^ Denifle, p. xxi. He is never, however, called a monk or Frater.

- ^ Denifle (1897), xxiv: certe talem gradum non Parisiis obtinuerat.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 87 note 1.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 87.

- ^ B. Haureau, Gallia christiana Tomus XIV, p. 580. Mollier, p. 7.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 144. D'Estouteville retained the diocese when he became a Cardinal on 18 December of the same year.

- ^ Denifle, p. xxiv.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 193. Cf. Gallia christiana XIII (Paris 1785), p. 272, where the Administratorship is place in the wrong interregnum.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 8 no. 18.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 134 and n. 2.

- ^ a b c David M. Cheney. "Catholic Hierarchy". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- ^ a b Gill (1996), p. 498.

- ^ G. Ferri, "Le carte dell archivio Liberiano del secolo X al XV," Archivio della Società romana di storia patria 30 (1907) 161-163. Eubel, II, p. 6 no. 37.

- ^ Gill (1996), p. 500, note 4.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 179 with note 1.

- ^ He took possession of his diocese by Procurator, and never visited the diocese in the next thirty years. He remembered the diocese, however, in his Testament. B. Hauréau, Gallia christiana, XVI (Paris 1865), p. 643. Eubel, II, p. 188.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 225, with note 2.

- ^ Gallia christiana XI, p. 90. Louis d'Harcourt was the son of Catherine de Bourbon, Guillaume's grandmother. Gallia christiana VI (Paris 1739), p. 103.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Estouteville, Guillaume d'". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 801.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 30, no. 143 (and cf. no. 146). Hefele, Histoire des conciles VII, ii, pp. 1220-1221.

- ^ Denifle (1897), Chartularium IV, no. 2690, pp. 713-734.

- ^ Noël Valois (1906). Histoire de la Pragmatique Sanction de Bourges sous Charles VII (in French and Latin). Paris: A. Picard. pp. clxxxiii–clxxxiv, 220–227. Bernard Guenée (1991). Between Church and State: The Lives of Four French Prelates in the Late Middle Ages. University of Chicago Press. pp. 316–318. ISBN 978-0-226-31032-9.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 31 no. 154.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 31, nos. 159 and 165.

- ^ Westfall, Carroll William (1974). "Alberti and the Vatican Palace Type". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 33 (2): 101–121, at pp. 102-103. doi:10.2307/988904. JSTOR 988904.

- ^ Eubel II, p. 10 note .2.

- ^ J.P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1447, retrieved: 2016-11-27.

- ^ J.P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1455, retrieved: 2016-11-27.

- ^ Ludwig Pastor (1906), History of the Popes, third edition Volume II (London: Kegan Paul), p. 544.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 13 note 2.

- ^ J.P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1458, retrieved: 2016-11-27.

- ^ Katherine, Walsh (1974). "The Beginnings of a National Protectorate: Curial Cardinals and the Irish Church in theFifteenth Century". Archivium Hibernicum. 32: 72–80, at p. 73. doi:10.2307/25529601. JSTOR 25529601.

- ^ Gregorovius, VII. 1, p. 176. Charles-Joseph Hefele, Histoire des conciles VII, ii (Paris Letouzeu 1916), pp. 1287-1333.

- ^ Denifle, p. xxiv, citing the Registers of Pius II in the Vatican Archives.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 8 no 11; p. 38 no. 324.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 14, note 4.

- ^ J.P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1464, retrieved: 2016-11-27.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 36, no. 278. If a cardinal was not in the Curia, he was not entitled to his share of the distributions during the time of his absence. This included nuncios and legates.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 15, note 9. Four of the absentees, unfortunately, were French.

- ^ Charles Bransom, The d'Estouteville Line, retrieved: 2016-11-25. Salvador Miranda, The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church: Della Rovere, O.F.M.Conv., Francesco Archived 2018-01-13 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved: 2016-11-25.

- ^ J.P. Adams, Sede Vacante 1471, retrieved: 2016-11-27.

- ^ He returned on 24 October 1473. Eubel, II, p. 38, no. 330.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 38, no. 318. He seems to have continued through 1473: no. 333. A new Chamberlain was elected on 24 January 1474: no. 342.

- ^ Eubel, II, p. 38, no. 322.

- ^ The Camerlengo, retrieved: 2016-11-27.

- ^ Elisabeth Chirol, Le Château de Gaillon (Paris: Picard 1952), Chapitre II, 1454-1463. A. Deville (1850). Comptes de dépenses de la construction du château de Gaillon (in French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. pp. xii, lii–lv.

- ^ Gregorovius, History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages Vol. VII, Part ii, p. 685.

- ^ Müntz, pp. 156-158.

- ^ V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese e d'altri edifici di Roma Volume V. (Roma: Bencini 1874), p. 18 no. 41.

- ^ Barbier de Montault, p. 8.

- ^ Müntz, pp. 285-291. The articles seem to comprise most of the materials belonging to the Cardinal's private chapel.

- ^ Gill (2001), p. 349.

- ^ Forcella, p. 111, no. 335, repeating the claim that d'Estouteville was a Benedictine monk. The 1865 inscription replaces that of 1637 (154 years after his death), which claimed that d'Estouteville was eighty years old.

- ^ David Abulafia (1995). The French descent into Renaissance Italy, 1494-95: antecedents and effects. Aldershot, UK: Variorum. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-86078-550-7. Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia was made guardian of d'Estouteville's sons in his Testament: Gill (2001), p. 347 note 1. Girolamo married Isabella Orsini in 1483; he was lord of Nemi, Genzano and Frascati and Count of Sarno in the Kingdom of Naples; he died c. 1495.

- ^ Annibale Ilari (1965). Frascati tra Medioevo e Rinascimento: con gli statuti esemplati nel 1515 e altri documenti (in Italian). Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. pp. 58–62. GGKEY:29HA6Y0J37F.

- ^ Gill (2001), p. 351, note 15.

- ^ Gill (2001), pp. 353-354.

- ^ Bransom, Charles. "Apostolic Succession & Episcopal Lineages in the Roman Catholic Church". Retrieved 2021-10-12.

Bibliography

edit- Barbier de Montault, X. (1859). Le Cardinal d'Estouteville bienfateur des églises de Rome (Angers 1859). [reprinted in: Xavier Barbier de Montault (1889). Oeuvres complètes de Mgr X. Barbier de Montault, prélat de la maison de Sa Sainteté (in French). Vol. Tome premier. Poitiers: Blais, Roy.]

- Breccia Fratadocchi, M. (1979). S. Agostino in Roma. Arte, storia, documenti. Roma 1979.

- Denifle, Henri (Heinrich) (ed.) (1897). Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis Tomus IV. Paris: Delalain (in French), pp. xx-xxiv.

- Doncoeur, P. and Lanhers, Y. (edd.) (1958). La réhabilitation de Jeanne la Pucelle: l'enquête du Cardinal d'Estouteville en 1452. Documents et recherches relatifs à Jeanne la Pucelle, Melun, 1958.

- Eubel, Conradus; Gulik, Guilelmus (1923). Hierarchia catholica. Vol. Tomus III (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana.

- Fisquet, Honoré (1864). La France pontificale (Gallia Christiana) (in French). Paris: Etienne Repos. pp. 189–195.

- Gallia christiana: in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa : De provincia Rotomagensi, ejusque metropoli ac suffraganeis Bajocensi, Abrincensi, Ebroicensi, Sagiensi, Lexoviensi ac Constantiensi ecclesiis (in Latin). Vol. Tomus undecimus (11). Paris: ex Typographia regia. 1759.

- Gill, Meredith (1992). A French Maecenas in the Roman Quattrocento: The Patronage of Cardinal Guillaume D'Estouteville (1439-1483). Ann Arbor: UMI Dissertation Services.

- Gill, Meredith J. (1996). ""Where the Danger Was Greatest": A Gallic Legacy in Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. 59 (4): 498–522. doi:10.2307/1482889. JSTOR 1482889.

- Gill, Meredith (2001). "Death and the Cardinal: The Two Bodies of Guillaume d'Estouteville". Renaissance Quarterly. 54 (2): 347–388. doi:10.2307/3176781. JSTOR 3176781. PMID 19068930. S2CID 373355.

- Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1900). The History of Rome in the Middle Ages, (translated from the fourth German edition by A. Hamilton) Volume 7 part 1 (London 1900).

- Guillaume d' Estouteville (Cardinal.) (1958). La réhabilitation de Jeanne la Pucelle: l'enquête du cardinal d'Estouteville en 1452 (in French). Paris: Librairie d'Argences.

- La Morandière, Gabriel; Lannelongue, Odilin Marc (1903). Histoire de la maison d'Estouteville en Normandie: Précédée de notes descriptives sur la contrée de Valmont (in French). Paris: Ch. Delagrave.

- Mollier, Marguerite (1906). Le cardinal Guillaume d'Estouteville et le Grand vicariat de Pontoise (in French). Paris: Plon-Nourrit.

- Müntz, Eugene (1882). Les arts à la cour des papes pendant le XVe et le XVIe siècle, III, Paris 1882.

- Ourliac, Paul (1938). "La Pragmatique Sanction et la légation en France du cardinal d'Estouteville ," Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire 55 (1938), 403-432.

External links

edit- Miranda, Salvador. "ESTOUTEVILLE, Guillaume d' (1403-1483)". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Florida International University.

- Esposito, Anna (1993). Estouteville, Guillaume d', Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 43. Retrieved: 2016-11-25.