Tangipahoa Parish ( /ˌtændʒɪpəˈhoʊə/) is a parish located on the southeastern border of the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 133,157.[2] The parish seat is Amite City,[3] while the largest city is Hammond. Southeastern Louisiana University is located in Hammond. Lake Pontchartrain borders the southeastern side of the parish.

Tangipahoa Parish | |

|---|---|

Columbia Theatre for the Performing Arts in Hammond | |

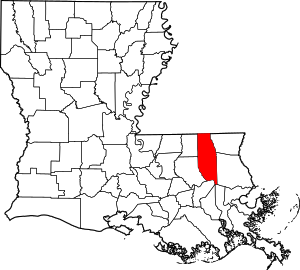

Location within the U.S. state of Louisiana | |

Louisiana's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 30°37′36″N 90°24′20″W / 30.62665°N 90.40568°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | March 6, 1869 |

| Named for | Acolapissa word meaning ear of corn or those who gather corn |

| Seat | Amite City |

| Largest city | Hammond |

| Area | |

• Total | 823 sq mi (2,130 km2) |

| • Land | 791 sq mi (2,050 km2) |

| • Water | 32 sq mi (80 km2) 3.9% |

| Population | |

• Total | 133,157 |

| • Density | 160/sq mi (62/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional districts | 1st, 5th |

| Website | www |

The name Tangipahoa comes from an Acolapissa word meaning "ear of corn" or "those who gather corn." The parish was organized in 1869 during the Reconstruction era.[4]

Tangipahoa Parish comprises the Hammond, LA Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is also included in the Baton Rouge–Hammond, LA Combined Statistical Area.[5] It is one of what are called the Florida Parishes, at one time part of West Florida.

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Tangipahoa Parish was created by Louisiana Act 85 on March 6, 1869, during the Reconstruction era.[6] The parish was assembled from territories taken from Livingston Parish, St. Helena Parish, St. Tammany Parish, and Washington Parish. It was named after the Tangipahoa River and the historic Tangipahoa Native American people of this area. Tangipahoa is the youngest parish in the Florida Parishes region of southern Louisiana.

Parts of this area had already been developed for sugar cane plantations when the parish was organized, and that industry depended on numerous African American laborers who were freedmen after the war. Mostly white yeomen farmers occupied areas in the piney woods and resisted planters' attempts at political dominance. African Americans comprised about one-quarter of the population overall in the Florida Parishes before the war but were prevalent in the plantation areas, where they had been enslaved laborers.[7]

The region developed rapidly during and after Reconstruction. Both physical and political conflicts arose in Tangipahoa Parish among interests related to construction of railroads, exploitation of timber, yeoman farmers in the piney woods keeping truck farms, and the beginning of manufacturing.

Sugar cane had depended on the labor of large gangs of enslaved African Americans before the Civil War. After the war and emancipation, some freedmen stayed to work on the plantations as laborers. Others moved to New Orleans and other cities, seeking different work. This area had rapid development and received a high rate of immigrants and migrants from other areas of the country. Through the turn of the twentieth century, the eastern Florida Parishes had the most white mob violence and highest rate of lynchings (primarily of black men) in southern Louisiana.[7]

Especially after Reconstruction, whites helped black communities with flowers and food. Piney woods whites resisted the planters' efforts to restore their political power, but imposed their own brutal violence on freedmen.

Tangipahoa Parish became more socially volatile by a "pronounced in-migration" of northerners (from the Midwest) and Sicilian immigrants, coupled with "industrial development along the Illinois Central Railroad, and crippling political factionalism."[7]

During the period of 1877–1950, a total of 24 blacks were lynched by whites in the parish as a means of racial terrorism and intimidation. This was the sixth highest total of any parish in Louisiana[8] and the highest number of any parish in southern Louisiana.[7] Twenty-two of these murders took place from 1879 to 1919, a time of heightened violence in the state. Unlike some other parishes, Tangipahoa did not have a high rate of legal executions of blacks; the whites operated outside the justice system altogether.[7] Among those lynched and hanged by a mob was Emma Hooper, a black woman who had shot and wounded a constable.[9]

In 1898 the Louisiana state legislature disenfranchised most blacks by raising barriers to voter registration. They effectively excluded blacks from politics for decades, until after passage and enforcement of federal civil rights legislation.

In the first half of the 20th century, many African Americans left Tangipahoa Parish to escape the racial violence and oppression of Jim Crow, moving to industrial cities in the Great Migration. Especially during and after World War II, they moved to the West Coast, where the buildup of the defense industry opened up new jobs. In the 21st century, blacks constitute a minority in the parish.

Timber, agriculture and industry are still important to the parish. It suffered flooding in 1932 and in the early 1980s. In 2016, Tangipahoa was one of many parishes declared a Federal disaster area due to historic flooding from rainfall and storms in both March and August.

Geography

editAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau, the parish has a total area of 823 square miles (2,130 km2), of which 791 square miles (2,050 km2) is land and 32 square miles (83 km2) (3.9%) is water.[10] Lake Pontchartrain lies on the southeast side of the parish.

Most of the parish south of Ponchatoula consists of Holocene coastal swamp and marsh—gray-to-black clays of high organic content and thick peat beds underlying freshwater marsh and swamp.[11]

Communities

editCities

edit- Hammond (largest municipality)

- Ponchatoula

Towns

edit- Amite City (parish seat)

- Independence

- Kentwood

- Roseland

Villages

editCensus-designated place

editOther unincorporated places

editDemographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 7,928 | — | |

| 1880 | 9,638 | 21.6% | |

| 1890 | 12,655 | 31.3% | |

| 1900 | 17,625 | 39.3% | |

| 1910 | 29,160 | 65.4% | |

| 1920 | 31,440 | 7.8% | |

| 1930 | 46,227 | 47.0% | |

| 1940 | 45,519 | −1.5% | |

| 1950 | 53,218 | 16.9% | |

| 1960 | 59,434 | 11.7% | |

| 1970 | 65,875 | 10.8% | |

| 1980 | 80,698 | 22.5% | |

| 1990 | 85,709 | 6.2% | |

| 2000 | 100,588 | 17.4% | |

| 2010 | 121,097 | 20.4% | |

| 2020 | 133,157 | 10.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] 1790-1960[13] 1900-1990[14] 1990-2000[15] 2010[16] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 79,825 | 59.95% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 39,770 | 29.87% |

| Native American | 409 | 0.31% |

| Asian | 942 | 0.71% |

| Pacific Islander | 23 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 4,946 | 3.71% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7,242 | 5.44% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 133,157 people, 46,526 households, and 31,420 families residing in the parish.

Government and politics

editThe parish is part of both Louisiana's 1st congressional district and Louisiana's 5th congressional district. Since the late 20th century most of the conservative, white-majority voters have left the Democratic Party and shifted to the Republican Party. African Americans have largely continued to support the Democratic Party and its candidates.

The parish government is governed by the Louisiana State Constitution and the Tangipahoa Parish Home Rule Charter. The Parish Government of Tangipahoa is headed by a parish president and a parish council (president-council government). The council is the legislative body of the parish, with authority under Louisiana State Constitution, the Parish Home Rule Charter, and laws passed by the Louisiana State Legislature. The Parish Sheriff is the chief law enforcement officer; other elected officers include the coroner, assessor, and clerk of court.

Keith Bardwell, justice of the peace for the parish's 8th ward (Robert, Louisiana), attracted attention in October 2009 for refusing to officiate the wedding of an interracial couple. Bardwell, a justice of the peace for 34 years, had concluded that "most black society does not readily accept offspring of such relationships, and neither does white society". He said he does not perform weddings for interracial marriages because "I don't want to put children in a situation they didn't bring on themselves."[18] Bardwell said he had refused to perform the weddings of four couples during the 2½-year period before the news of his actions was publicized, resigned effective November 3, 2009.[19] Governor Bobby Jindal said that the resignation was "long overdue."[19]

Despite the parish's Republican leanings, the parish is also the home of Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards. Edwards won over 60% of the parish vote in 2015 and carried the parish again in 2019, outperforming Democratic presidential candidates by over 30 points in both elections.

Parish Council

editTangipahoa Parish is governed by an elected ten-member Council, each representing a geographic district and roughly equal populations. As of October 2016 its chairman was Bobby Cortez. Kristen Pecararo is the clerk of the council.[20]

President of Tangipahoa Parish

editIn 1986, the former governing body of Tangipahoa Parish, the Tangipahoa Police Jury, and the voters of the Parish approved a "home rule charter" style of government. The charter provided for the election of a parish president, essentially a parish-wide mayor. Democrat Gordon A. Burgess was elected to an initial one-year term and re-elected the following year for a four-year term. Burgess was repeatedly re-elected as parish president until he retired in 2015.

In 2016, Republican businessman Robert "Robby" Miller succeeded Burgess. In April 2016, the Parish hired its first chief administrative officer, Shelby "Joe" Thomas, Jr. to handle operating functions.[21]

| President | Terms of Office | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Gordon Burgess | October 27, 1986 – January 11, 2016 | Democratic |

| Robby Miller | January 11, 2016 – incumbent | Republican |

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 37,806 | 65.57% | 18,887 | 32.76% | 968 | 1.68% |

| 2016 | 33,959 | 64.79% | 16,878 | 32.20% | 1,579 | 3.01% |

| 2012 | 31,590 | 63.06% | 17,722 | 35.37% | 787 | 1.57% |

| 2008 | 31,434 | 64.68% | 16,438 | 33.82% | 730 | 1.50% |

| 2004 | 26,181 | 62.14% | 15,345 | 36.42% | 609 | 1.45% |

| 2000 | 20,421 | 54.96% | 15,843 | 42.64% | 891 | 2.40% |

| 1996 | 15,517 | 41.28% | 18,617 | 49.53% | 3,457 | 9.20% |

| 1992 | 14,128 | 41.26% | 15,194 | 44.37% | 4,923 | 14.38% |

| 1988 | 16,669 | 54.32% | 13,527 | 44.08% | 492 | 1.60% |

| 1984 | 19,580 | 60.10% | 12,799 | 39.29% | 200 | 0.61% |

| 1980 | 15,187 | 48.46% | 15,272 | 48.73% | 883 | 2.82% |

| 1976 | 9,242 | 38.02% | 14,432 | 59.36% | 637 | 2.62% |

| 1972 | 11,607 | 62.89% | 5,227 | 28.32% | 1,623 | 8.79% |

| 1968 | 2,907 | 13.86% | 4,983 | 23.75% | 13,088 | 62.39% |

| 1964 | 9,732 | 57.79% | 7,109 | 42.21% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 3,285 | 22.89% | 6,648 | 46.32% | 4,418 | 30.79% |

| 1956 | 5,788 | 51.75% | 4,831 | 43.19% | 566 | 5.06% |

| 1952 | 5,166 | 46.90% | 5,850 | 53.10% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 1,287 | 17.37% | 2,184 | 29.48% | 3,937 | 53.15% |

| 1944 | 1,572 | 26.24% | 4,419 | 73.76% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 1,284 | 17.87% | 5,900 | 82.09% | 3 | 0.04% |

| 1936 | 1,374 | 22.90% | 4,624 | 77.07% | 2 | 0.03% |

| 1932 | 455 | 9.36% | 4,404 | 90.58% | 3 | 0.06% |

| 1928 | 1,415 | 33.30% | 2,834 | 66.70% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 479 | 22.76% | 1,626 | 77.24% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1920 | 440 | 22.67% | 1,501 | 77.33% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1916 | 159 | 10.62% | 1,326 | 88.58% | 12 | 0.80% |

| 1912 | 40 | 3.02% | 1,061 | 80.02% | 225 | 16.97% |

Law enforcement

editThe Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff's Office is headquartered in Hammond.[23] The Sheriff's office was excluded from a DEA task force in 2016 after the Justice Department charged two deputies with stealing money and drugs seized in raids.[24]

Education

editThe parish is served by the Tangipahoa Parish School System.[25] Southeastern Louisiana University is located in Hammond.

On seven occasions, the American Civil Liberties Union has sued the Tangipahoa Parish School Board, along with other defendants, for having allegedly sponsored and promoted religion in teacher-led school activities.[26]

Education

editThe elected school board governs and oversees the Tangipahoa Parish School System (TPSS). The Board has a long history of racial discrimination in the hiring of teachers. In 1975, it was ordered to ensure one-third of the teaching staff were Black. Both the Board and the Court ignored the mandate for more than thirty years. During the period from 1998 to 2008, the Board hired fewer Black teachers than any other school system in the state. In 2010, a second ruling strengthened the first.[27]

National Guard

editThe parish is home to the 204th Theater Airfield Operations Group and the Forward Support Company of the 205th Engineer Battalion. This 205th Engineer Battalion is a component of the 225th Engineer Brigade of the Louisiana National Guard. These units reside within the city of Hammond. A detachment of the 1021st Engineer Company (Vertical) resides in Independence, Louisiana. The 236th Combat Communications Squadron of the Louisiana Air National Guard also resides at the Hammond Airport.

Transportation

editRailroads

editAmtrak's daily City of New Orleans long-distance train stops in Hammond, both northbound (to Chicago) and southbound. It serves about 15,000 riders a year, and Hammond-Chicago is the ninth-busiest city pair on the route.[28]

The historic main line of the Illinois Central that carries freight through the parish is now part of CN. It continues to be busy.

Highways

edit- Interstate 12

- Interstate 55

- U.S. Route 51

- U.S. Route 190

- Louisiana Highway 10

- Louisiana Highway 16

- Louisiana Highway 22

- Louisiana Highway 38

- Louisiana Highway 40

- Louisiana Highway 440

- Louisiana Highway 442

- Louisiana Highway 443

- Louisiana Highway 445

- Louisiana Highway 1040

- Louisiana Highway 1045

- Louisiana Highway 1046

- Louisiana Highway 1048

- Louisiana Highway 1049

- Louisiana Highway 1050

- Louisiana Highway 1051

- Louisiana Highway 1053

- Louisiana Highway 1054

- Louisiana Highway 1055

- Louisiana Highway 1056

- Louisiana Highway 1057

- Louisiana Highway 1061

- Louisiana Highway 1062

- Louisiana Highway 1063

- Louisiana Highway 1064

- Louisiana Highway 1065

- Louisiana Highway 1249

- Louisiana Highway 3158

- Louisiana Highway 3234

Notable people

edit- Robert Alford, professional football player, Atlanta Falcons, Arizona Cardinals

- Chris Broadwater, former District 86 state representative, resides in Hammond

- Nick Bruno, president of University of Louisiana at Monroe

- Hodding Carter, 20th-century journalist

- John L. Crain, president of Southeastern Louisiana University

- Donald Dykes, former professional football player, New York Jets and San Diego Chargers

- John Bel Edwards, former Governor of Louisiana; former Minority Leader of Louisiana House of Representatives; former District 72 state representative, resides in Amite

- C. B. Forgotston, political activist

- Barbara Forrest, critic of intelligent design

- Tim Gautreaux, writer

- Kevin Hughes, former professional football player, St. Louis Rams and Carolina Panthers

- Bolivar E. Kemp, U.S. representative, 1925–1933

- Bolivar Edwards Kemp, Jr., Louisiana Attorney General, 1948–1952

- Wade Miley, professional baseball pitcher

- Harlan Miller, professional football player, Arizona Cardinals, Washington Redskins

- James H. Morrison, represented Louisiana's 6th congressional district from 1943 to 1967

- Kim Mulkey, college basketball player, United States Olympic Team, LSU head women's basketball coach

- Rufus Porter, former professional football player

- Billy Reid, fashion designer

- Weldon Russell, former state representative from Tangipahoa and St. Helena parishes

- Britney Spears, entertainer

- DeVonta Smith, professional football player, Philadelphia Eagles, 2020 Heisman Trophy Winner, Alabama Crimson Tide football

- Jackie Smith, former professional football player, St. Louis Cardinals and Dallas Cowboys, NFL Hall of Famer

- Irma Thomas, Grammy Award-winning singer

- LaBrandon Toefield, former professional football player, Jacksonville Jaguars and Carolina Panthers

- Earl Wilson, former major league baseball player for Boston Red Sox, Detroit Tigers and San Diego Padres

- Harry D. Wilson, Louisiana state representative and state agriculture commissioner; pushed for the establishment of the town of Independence in 1912

- Justin Wilson, chef and humorist

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana; United States". QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Tangipahoa Parish". Center for Cultural and Eco-Tourism. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ Van Leuven, Andrew J. (August 4, 2023). "Recent Changes to U.S. Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas". Andrew J. Van Leuven, Ph.D. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Acts passed by the General Assembly of the state: To Create the Parish of Tangipahoa". HathiTrust Digital Library. Louisiana State Legislature: 83–86. 1869. hdl:2027/pst.000018406139. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Michael James Pfeifer, Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874-1947, University of Illinois Press, 2004, pp. 83-84

- ^ Lynching in America, Third Edition: Supplement by County Archived October 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, p. 6, Equal Justice Initiative, Mobile, AL, 2017

- ^ Pfeifer (2004), Rough Justice, p. 198, Footnote #104

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ McCulloh, R. P.; P. V. Heinrich; J. Snead (2003). "Ponchatoula 30 x 60 Minute Geologic Quadrangle" (PDF). Louisiana Geological Survey. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "JP refuses to marry couple". Daily Star (Hammond). October 15, 2009. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

Bardwell said he came to the conclusion that most black society does not readily accept offspring of such relationships, and neither does white society.... "I don't do interracial marriages because I don't want to put children in a situation they didn't bring on themselves," Bardwell said. "In my heart, I feel the children will later suffer."

- ^ a b "US judge in mixed-race row quits". BBC News. November 4, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ Council page on Parish website, accessed December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Thomas named Tangipahoa Parish Government's first CAO". ActionNews17. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ "About Us". Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff's Office. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Grueskin, Caroline; Mustian, Jim; Roberts III, Faimon A. (September 1, 2018). "In strip club sting, undercover Louisiana agents 'cross the line' with big 'no-no,' experts say". The Advocate (Louisiana). Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Official website of the Tangipahoa Parish School System

- ^ Mitchell, David. "School board sued over prayer", Baton Rouge Morning Advocate, Capital City Press, p. B01.[when?]

- ^ Anderson, Melinda (January 23, 2018). "A Root Cause of the Teacher-Diversity Problem". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ "Amtrak Fact Sheet" (PDF). National Association of Railroad Passengers. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

External links

edit- Official website

- "History of Tangipahoa Parish". Tangipahoa Parish Convention & Visitors Bureau.

- "Explore the History and Culture of Southeastern Louisiana". Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary. National Park Service. September 26, 2000.