Trenton is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. It was the capital of the United States from November 1 until December 24, 1784.[24][25] Trenton and Princeton are the two principal cities of the Trenton–Princeton metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses those cities and all of Mercer County for statistical purposes and constitutes part of the New York combined statistical area by the U.S. Census Bureau.[26] However, Trenton directly borders the Philadelphia metropolitan area to its west, and the city was part of the Philadelphia combined statistical area from 1990 until 2000.[27]

Trenton, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

Downtown Trenton along the Delaware River Turning Point Church | |

| Nickname(s): The Capital City, Turning Point of the Revolution | |

| Motto(s): "Trenton Makes, The World Takes"[1] | |

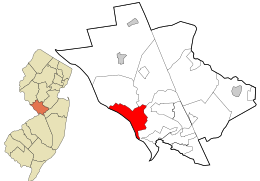

Location of Trenton in Mercer County highlighted in red (right). Inset map: Location of Mercer County in New Jersey highlighted in orange (left). | |

| |

| Coordinates: 40°13′13″N 74°45′57″W / 40.22028°N 74.76583°W[2][3] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Mercer |

| Founded | June 3, 1719 |

| Incorporated | November 13, 1792 |

| Named for | William Trent |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | Reed Gusciora (term ends December 31, 2026)[4][5] |

| • Administrator | Adam E. Cruz[6] |

| • Municipal clerk | Brandon Garcia[7] |

| Area | |

| 8.20 sq mi (21.25 km2) | |

| • Land | 7.61 sq mi (19.70 km2) |

| • Water | 0.60 sq mi (1.55 km2) 7.62% |

| • Rank | 229th of 565 in state 9th of 12 in county[2] |

| Elevation | 59 ft (18 m) |

| Population | |

| 90,871 | |

| 89,620 | |

| • Rank | 382nd in country (as of 2022)[15] 10th of 565 in state 2nd of 12 in county[17] |

| • Density | 11,989.8/sq mi (4,629.3/km2) |

| • Rank | 25th of 565 in state 1st of 12 in county[17] |

| • Urban | 370,422 (US: 112th)[11] |

| • Urban density | 2,782.4/sq mi (1,074.3/km2) |

| • Metro | 387,340 (US: 143rd)[10] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Codes | |

| Area code | 609[20] |

| FIPS code | 3402174000[2][21][22] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885421[2][23] |

| Website | trentonnj.org |

In the 2020 United States census, Trenton was the state's 10th-most-populous municipality,[28] with a population of 90,871,[13][14] an increase of 5,958 (+7.0%) from the 2010 census count of 84,913,[29][30] which in turn had reflected a decline of 490 (−0.6%) from the 85,403 counted in the 2000 census.[31] The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 89,661 in 2022,[13] ranking the city the 382nd-most-populous in the country.[15] Trenton is the only city in New Jersey that serves three separate commuter rail transit systems (Amtrak, NJ Transit, and SEPTA), and the city has encouraged a spate of transit-oriented development since 2010.[32]

Trenton dates back at least to June 3, 1719, when mention was made of a constable being appointed for Trenton while the area was still part of Hunterdon County. Boundaries were recorded for Trenton Township as of March 2, 1720.[33] A courthouse and jail were constructed in Trenton around 1720, and the Freeholders of Hunterdon County met annually in Trenton.[34]

Abraham Hunt was appointed in 1764 as Trenton's first Postmaster.[35][36] On November 25, 1790, Trenton became New Jersey's capital, and by November 13, 1792, the City of Trenton was formed within Trenton Township. Trenton Township was incorporated as one of New Jersey's initial group of 104 townships by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on February 21, 1798. On February 22, 1834, portions of Trenton Township were taken to form Ewing Township. The remaining portion of Trenton Township was absorbed by the city on April 10, 1837. A series of annexations took place over a 50-year period with the city absorbing South Trenton (April 14, 1851), portions of Nottingham Township (April 14, 1856), Chambersburg Township and Millham Township (both on March 30, 1888), and Wilbur (February 28, 1898). Portions of Ewing Township and Hamilton Township were annexed to Trenton on March 23, 1900.[33][37]

History

editThe earliest known inhabitants of the area that is today Trenton were the Lenape Native Americans,[38] specifically the Axion band who were the largest tribe on the Delaware River in the mid-17th century.[39]

The first European settlement in what would become Trenton was established by Quakers in 1679, in the region then called the Falls of the Delaware, led by Mahlon Stacy from Handsworth, Sheffield, England. Quakers were being persecuted in England at this time, and North America provided an opportunity to exercise their religious freedom.[40]

By 1719, the town adopted the name "Trent-towne", after William Trent, one of its leading landholders who purchased much of the surrounding land from Stacy's family. This name was later shortened to "Trenton".[41][42][43]

The first municipal boundaries were recorded on March 2, 1720, and a courthouse and jail were constructed around the same time.[44]

In 1758, the Old Barracks were built to house British soldiers during the French and Indian War. On January 19, 1764, Benjamin Franklin, Postmaster General of the colonies, appointed Abraham Hunt, a Lieutenant Colonel in the New Jersey Hunterdon County militia and prominent merchant in Trenton, as the city's first postmaster. Hunt was again appointed Trenton's postmaster on October 13, 1775, shortly after the American Revolutionary War broke out.[35][36]

During the American Revolutionary War, Trenton was the site of the Battle of Trenton. On December 25–26, 1776, George Washington and his army crossed the icy Delaware River to Trenton, where they defeated Hessian troops garrisoned there.[45] The second battle of Trenton, Battle of the Assunpink Creek, was fought here on January 2, 1777.[46] After the war, the Congress of the Confederation met for two months at the French Arms Tavern from November 1, 1784, to December 24, 1784.[25] While the city was preferred by New England and other northern states as a permanent capital for the new country, the southern states ultimately prevailed in their choice of a location south of the Mason–Dixon line.[47] On April 21, 1789, the city hosted a reception for George Washington on his journey to New York City for his first inauguration.[48] The Trenton Battle Monument, a 150-foot (46 m) granite column topped with a statue of George Washington, was built in 1893 to commemorate the battle.[49]

Trenton became the state capital in 1790, but prior to that year the New Jersey Legislature often met in the city.[50] The city was incorporated on November 13, 1792.[33] In 1792, the New Jersey State House was built, making it the third-oldest state house in the country.[49] In 1799, the federal government relocated its offices to Trenton for a period of several months, following an outbreak of yellow fever in the then-capital of Philadelphia.[51]

During the War of 1812, the United States Army's primary hospital was at a site on Broad Street.[52]

Trenton had maintained an iron industry since the 1730s and a pottery industry since at least 1723. The completion of both the Delaware and Raritan Canal and the Camden and Amboy Railroad in the 1830s spurred industrial development in Trenton. In 1845, industrialist Peter Cooper opened a rolling mill. In 1848, engineer John Roebling moved his wire rope mill to the city, where suspension cables for bridges were manufactured, including the Brooklyn Bridge. In the late 19th century, Walter Scott Lenox was internationally recognized for the fine china made in his Trenton factory. Throughout the 19th century, Trenton grew steadily, as European immigrants came to work in its pottery and wire rope mills. Trenton became known as an industrial hub for railroads, trucking, rubber, plastics, metalworking, electrical, automobile parts, glass, and textiles industries.[49]

In 1837, with the population now too large for government by council, a new mayoral government was adopted, with by-laws that remain in operation to this day.[53] During the latter half of the century, Trenton annexed multiple municipalities: South Trenton Borough on April 14, 1851, portions of Nottingham Township on April 14, 1856, Chambersburg and Millham Township on March 30, 1888, and Wilbur borough on February 28, 1898.[44]

In 1855, the College of New Jersey was founded in Trenton. In 1865, Rider University was also founded in Trenton. Mercer Community College began in Trenton in 1966.[49]

The Trenton Six were a group of black men arrested for the alleged murder of an elderly white shopkeeper in January 1948 with a soda bottle. They were arrested without warrants, denied lawyers and sentenced to death based on what were described as coerced confessions. With the involvement of the Communist Party and the NAACP, there were several appeals, resulting in a total of four trials. Eventually the accused men (with the exception of one who died in prison) were released. The incident was the subject of the book Jersey Justice: The Story of the Trenton Six, written by Cathy Knepper.[54][55]

In the 1950s, the State of New Jersey purchased a large portion of what was then Stacy Park, a large riverfront park located next to downtown that contained large open lawns, landscaping, and promenades. Much of the park was demolished to make way for the construction of Route 29, despite the protests toward its construction. After it was built, the area was then mostly filled with parking lots and scattered state office buildings, disconnecting the city from the riverfront.[56]

Riots of 1968

editThe Trenton Riots of 1968 were a major civil disturbance that took place during the week following the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis on April 4. Race riots broke out nationwide following the murder of the civil rights activist. More than 200 Trenton businesses, mostly in Downtown, were ransacked and burned. More than 300 people, most of them young black men, were arrested on charges ranging from assault and arson to looting and violating the mayor's emergency curfew. In addition to 16 injured policemen, 15 firefighters were treated at city hospitals for injuries suffered while fighting raging blazes or inflicted by rioters. Area residents pulled false alarms and would then throw bricks at firefighters responding to the alarm boxes. This experience, along with similar experiences in other major cities, effectively ended the use of open-cab fire engines. As an interim measure, the Trenton Fire Department fabricated temporary cab enclosures from steel deck plating until new equipment could be obtained. The losses incurred by downtown businesses were initially estimated by the city to be $7 million, but the total of insurance claims and settlements came to $2.5 million.[57]

Trenton's Battle Monument neighborhood was hardest hit. Since the 1950s, North Trenton had witnessed a steady exodus of middle-class residents, and the riots spelled the end for North Trenton. By the 1970s, the region had become one of the most blighted and crime-ridden in the city.[58]

Geography

editAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 8.21 square miles (21.25 km2), including 7.58 square miles (19.63 km2) of land and 0.63 square miles (1.62 km2) of water (7.62%).[2][3] In terms of land area, Trenton is also the second-smallest of the United States capital cities, behind Annapolis, Maryland.[59]

Several bridges across the Delaware River connect Trenton to Morrisville, Pennsylvania, all of which are operated by the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission.[60] The Trenton–Morrisville Toll Bridge, originally constructed in 1952, stretches 1,324 feet (404 m), carrying U.S. Route 1.[61] The Lower Trenton Bridge, bearing the legend "Trenton Makes The World Takes Bridge", is a 1,022-foot (312 m) span that was constructed in 1928 on the site of a bridge that dates back to 1804.[62] The Calhoun Street Bridge, dating back to 1884, is 1,274 feet (388 m) long.[63]

Trenton is located near the geographic center of the state, which is located 5 miles (8.0 km) southeast of the city.[64][65] The city is sometimes included as part of North Jersey and as the southernmost city of the Tri-State Region, while others consider it a part of South Jersey and thus, the northernmost city of the Delaware Valley.[66]

However, Mercer County constitutes its own metropolitan statistical area, the Trenton-Princeton MSA.[26] Locals consider Trenton to be a part of Central Jersey, and thus part of neither region. They are generally split as to whether they are within New York or Philadelphia's sphere of influence. While it is geographically closer to Philadelphia, many people who have recently moved to the area commute to New York City, and have moved there to escape the New York region's high housing costs.[citation needed]

Trenton is one of two state capitals that border another state—the other being Carson City, Nevada.[67] It is also one of the seven state capitals located within the Piedmont Plateau.

Trenton borders Ewing Township, Hamilton Township and Lawrence Township in Mercer County; and Falls Township, Lower Makefield Township and Morrisville in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, across the Delaware River in Pennsylvania.[68][69][70]

The Northeast Corridor goes through Trenton. A straight line drawn between Center City, Philadelphia and Downtown Manhattan would pass within 2000 feet of the New Jersey State House.

Neighborhoods

editTrenton is home to numerous neighborhoods and sub-neighborhoods. The main neighborhoods are taken from the four cardinal directions (North, South, East, and West). Trenton was once home to large Italian, Hungarian, and Jewish communities, but, since the 1950s, demographic shifts have changed the city into a relatively segregated urban enclave of middle and lower income African Americans and newer immigrants, many of whom arrive from Latin America. Italians are scattered throughout the city, but a distinct Italian community is centered in the Chambersburg neighborhood, in South Trenton.[71] This community has been in decline since the 1970s, largely due to economic and social shifts to the suburbs surrounding the city. Today Chambersburg has a large Latino community. Many of the Latino immigrants are from Mexico, Guatemala and Nicaragua. There is also a significant and growing Asian community in the Chambersburg neighborhood primarily made up of Burmese and Bhutanese/Nepali refugees.

The North Ward, once a mecca for the city's middle class, is now one of the most economically distressed, torn apart by race riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Nonetheless, the area still retains many important architectural and historic sites. North Trenton still has a large Polish-American neighborhood that borders Lawrence Township, many of whom attend St. Hedwig's Roman Catholic Church on Brunswick Avenue. St. Hedwig's church was built in 1904 by Polish immigrants, many of whose families still attend the church. North Trenton is also home to the historic Shiloh Baptist Church—one of the largest houses of worship in Trenton and the oldest African American church in the city, founded in 1888.[72] The church is currently pastored by Rev. Darrell L. Armstrong, who carried the Olympic torch in 2002 for the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. Also located just at the southern tip of North Trenton is the city's Battle Monument, also known as "Five Points". It is a 150 ft (46 m) structure that marks the spot where George Washington's Continental Army launched the Battle of Trenton during the American Revolutionary War. It faces downtown Trenton and is a symbol of the city's historic past.[73]

South Ward is a diverse neighborhood, home to many Latin American, Italian-American, and African American residents.[74]

East Ward is the smallest neighborhood in Trenton and is home to the Trenton Transit Center and Trenton Central High School. The Chambersburg neighborhood is within the East Ward and was once noted in the region as a destination for its many Italian restaurants and pizzerias. With changing demographics, many of these businesses have either closed or relocated to suburban locations. West Ward is the home of Trenton's more suburban neighborhoods.

Neighborhoods in the city include:[75]

- Downtown Trenton

- East Trenton

- Western Trenton (not the same as West Trenton, which is outside the city limits in Ewing)

- Berkeley Square

- Cadwalader Heights

- Central West

- Fisher/Richey/Perdicaris

- Glen Afton

- Hillcrest

- Hiltonia

- Parkside

- Pennington/Prospect

- Stuyvesant/Prospect

- The Island

- West End

- South Trenton

- Chambersburg

- Chestnut Park

- Duck Island

- Franklin Park

- Lamberton/Waterfront

- North Trenton

- Battle Monument (Five Points)

- North 25

- Top Road

Climate

editAccording to the Köppen climate classification, Trenton lies in the transition from a cooler humid continental climate (Dfa) and the warmer humid subtropical (Cfa), and precipitation fairly evenly distributed through the year. The Cfa climate is the result of adiabatic warming of the Appalachians, low altitude and proximity to the coast without being on the immediate edge for moderate temperatures.[76]

Summers are hot and humid, with a July daily average of 76.3 °F (24.6 °C); temperatures reaching or exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) occur on 21.8 days.[77] Episodes of extreme heat and humidity can occur with heat index values reaching 100 °F (38 °C). Extremes in air temperature have ranged from −14 °F (−26 °C) on February 9, 1934, up to 106 °F (41 °C) as recently as July 22, 2011.[78] However, air temperatures reaching 0 °F (−18 °C) or 100 °F (38 °C) are uncommon.

Winters are cold and damp: the daily average temperature in January is 32.0 °F (0.0 °C),[77] and temperatures at or below 10 °F (−12 °C) occur on 3.9 nights annually, while there are 17 days where the temperature fails to rise above freezing.[79] Episodes of extreme cold and wind can occur with wind chill values below 0 °F (−18 °C), every few years. The plant hardiness zone at the Trenton Municipal Court is 7a with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of 1.2 °F (−17.1 °C).[80]

The average precipitation is 45.47 inches (115 cm) per year, which is fairly evenly distributed through the year.[77][79] The driest month on average is February, with 2.63 in (67 mm) of precipitation on average, while the wettest month is July with 4.39 in (11 cm) of rainfall on average which corresponds with the annual peak in thunderstorm activity.[77][79] The all-time single-day rainfall record is 7.25 in (18.4 cm) on September 16, 1999, during the passage of Hurricane Floyd.[79] The all-time monthly rainfall record is 14.55 in (37.0 cm) in August 1955, due to the passage of Hurricane Connie and Hurricane Diane. The wettest year on record was 1996, when 67.90 in (172 cm) of precipitation fell. On the flip side, the driest month on record was October 1963, when only 0.05 in (0.1 cm) of rain was recorded. The 28.79 in (73 cm) of precipitation recorded in 1957 were the lowest ever for the city.[81]

Snowfall can vary even more year to year. The average seasonal (November–April) snowfall total is 24 to 30 inches (61 to 76 cm), but has ranged from as low as 2 in (5.1 cm) in the winter of 1918–1919 to as high as 76.5 in (194.3 cm) in 1995–1996, which included the greatest single-storm snowfall, the Blizzard of January 7–8, 1996, when 24.2 inches (61.5 cm) of snow fell.[82] The average snowiest month is February which corresponds with the annual peak in nor'easter activity.

| Climate data for Trenton, New Jersey (Trenton–Mercer Airport) 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1865–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

78 (26) |

87 (31) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

94 (34) |

83 (28) |

76 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 62.7 (17.1) |

62.7 (17.1) |

74.2 (23.4) |

83.0 (28.3) |

88.6 (31.4) |

93.4 (34.1) |

96.3 (35.7) |

94.3 (34.6) |

89.7 (32.1) |

81.4 (27.4) |

72.0 (22.2) |

64.2 (17.9) |

97.2 (36.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.7 (4.3) |

42.8 (6.0) |

50.8 (10.4) |

62.9 (17.2) |

72.4 (22.4) |

81.0 (27.2) |

86.0 (30.0) |

84.0 (28.9) |

77.1 (25.1) |

65.5 (18.6) |

54.5 (12.5) |

44.4 (6.9) |

63.4 (17.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 32.0 (0.0) |

34.3 (1.3) |

41.7 (5.4) |

52.5 (11.4) |

62.0 (16.7) |

71.0 (21.7) |

76.3 (24.6) |

74.4 (23.6) |

67.4 (19.7) |

55.7 (13.2) |

45.4 (7.4) |

36.8 (2.7) |

54.1 (12.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 24.3 (−4.3) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

32.7 (0.4) |

42.1 (5.6) |

51.6 (10.9) |

60.9 (16.1) |

66.6 (19.2) |

64.8 (18.2) |

57.7 (14.3) |

45.9 (7.7) |

36.3 (2.4) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

44.8 (7.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 7.2 (−13.8) |

10.0 (−12.2) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

37.7 (3.2) |

48.3 (9.1) |

57.0 (13.9) |

54.4 (12.4) |

43.2 (6.2) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

14.8 (−9.6) |

5.1 (−14.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) |

−14 (−26) |

0 (−18) |

11 (−12) |

31 (−1) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

39 (4) |

34 (1) |

21 (−6) |

9 (−13) |

−8 (−22) |

−16 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.29 (84) |

2.63 (67) |

3.97 (101) |

3.63 (92) |

3.99 (101) |

4.25 (108) |

4.39 (112) |

4.22 (107) |

4.09 (104) |

3.79 (96) |

3.18 (81) |

4.04 (103) |

45.47 (1,155) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.9 (20) |

8.6 (22) |

4.9 (12) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.5 (1.3) |

4.3 (11) |

26.8 (67.85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.1 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 10.8 | 10.0 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 8.5 | 11.0 | 125.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.6 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 14.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65.4 | 61.7 | 58.0 | 57.0 | 62.1 | 66.1 | 66.2 | 68.8 | 69.8 | 68.8 | 66.9 | 66.5 | 64.8 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 21.7 (−5.7) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

37.7 (3.2) |

48.7 (9.3) |

59.4 (15.2) |

63.9 (17.7) |

63.5 (17.5) |

57.0 (13.9) |

45.6 (7.6) |

35.9 (2.2) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

42.7 (5.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 163.1 | 169.7 | 207.4 | 227.2 | 248.1 | 262.8 | 269.2 | 252.5 | 215.0 | 201.5 | 149.3 | 140.1 | 2,505.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 54 | 57 | 56 | 57 | 56 | 58 | 59 | 59 | 57 | 58 | 50 | 48 | 56 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun 1961–1981)[83][84][85] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: PRISM Climate Group (humidity and dew point)[86] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1,946 | — | |

| 1810 | 3,000 | — | |

| 1820 | 3,942 | 31.4% | |

| 1830 | 3,925 | −0.4% | |

| 1840 | 4,035 | * | 2.8% |

| 1850 | 6,461 | 60.1% | |

| 1860 | 17,228 | * | 166.6% |

| 1870 | 22,874 | 32.8% | |

| 1880 | 29,910 | 30.8% | |

| 1890 | 57,458 | * | 92.1% |

| 1900 | 73,307 | 27.6% | |

| 1910 | 96,815 | 32.1% | |

| 1920 | 119,289 | 23.2% | |

| 1930 | 123,356 | 3.4% | |

| 1940 | 124,697 | 1.1% | |

| 1950 | 128,009 | 2.7% | |

| 1960 | 114,167 | −10.8% | |

| 1970 | 104,638 | −8.3% | |

| 1980 | 92,124 | −12.0% | |

| 1990 | 88,675 | −3.7% | |

| 2000 | 85,403 | −3.7% | |

| 2010 | 84,913 | −0.6% | |

| 2020 | 90,871 | 7.0% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 89,620 | [13][15][16] | −1.4% |

| Population sources: 1790–1920[87] 1840[88] 1850–1870[89] 1850[90] 1870[91] 1880–1890[92] 1910–1930[93] 1940–2000[94] 2000[95][96] 2010[29][30] 2020[13][14] * = Territory change in previous decade.[33] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 1990[97] | Pop 2000[98] | Pop 2010[99] | Pop 2020[100] | % 1990 | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 33,247 | 21,022 | 11,442 | 8,510 | 37.49% | 24.62% | 13.47% | 9.36% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 42,089 | 43,497 | 42,286 | 38,386 | 47.46% | 50.93% | 49.80% | 42.24% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 189 | 164 | 219 | 144 | 0.21% | 0.19% | 0.26% | 0.16% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 474 | 684 | 923 | 592 | 0.53% | 0.80% | 1.09% | 0.65% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | N/A | 65 | 30 | 24 | N/A | 0.08% | 0.04% | 0.03% |

| Other Race alone (NH) | 146 | 127 | 106 | 440 | 0.16% | 0.15% | 0.12% | 0.48% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | N/A | 1,453 | 1,286 | 1,870 | N/A | 1.70% | 1.51% | 2.06% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 12,530 | 18,391 | 28,621 | 40,905 | 14.13% | 21.53% | 33.71% | 45.01% |

| Total | 88,675 | 85,403 | 84,913 | 90,871 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

editThe 2010 United States census counted 84,913 people, 28,578 households, and 17,747 families in the city. The population density was 11,101.9 per square mile (4,286.5/km2). There were 33,035 housing units at an average density of 4,319.2 per square mile (1,667.7/km2). The racial makeup was 26.56% (22,549) White, 52.01% (44,160) Black or African American, 0.70% (598) Native American, 1.19% (1,013) Asian, 0.13% (110) Pacific Islander, 15.31% (13,003) from other races, and 4.10% (3,480) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 33.71% (28,621) of the population.[29]

Of the 28,578 households, 32.0% had children under the age of 18; 25.1% were married couples living together; 28.1% had a female householder with no husband present and 37.9% were non-families. Of all households, 30.8% were made up of individuals and 9.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.79 and the average family size was 3.40.[29]

25.1% of the population were under the age of 18, 11.0% from 18 to 24, 32.5% from 25 to 44, 22.6% from 45 to 64, and 8.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32.6 years. For every 100 females, the population had 106.5 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 107.2 males.[29]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $36,601 (with a margin of error of +/− $1,485) and the median family income was $41,491 (+/− $2,778). Males had a median income of $29,884 (+/− $1,715) versus $31,319 (+/− $2,398) for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,400 (+/− $571). About 22.4% of families and 24.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 36.3% of those under age 18 and 17.5% of those age 65 or over.[101]

Economy

editTrenton was a major manufacturing center in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One relic of that era is the slogan "Trenton Makes, The World Takes", which is displayed on the Lower Free Bridge (just north of the Trenton–Morrisville Toll Bridge).[102] The city adopted the slogan in 1917 to represent Trenton's then-leading role as a major manufacturing center for rubber, wire rope, ceramics and cigars. It was home to American Standard's largest plumbing fixture manufacturing facility.[103]

Along with many other United States cities in the 1970s, Trenton fell on hard times when manufacturing and industrial jobs declined. Concurrently, state government agencies began leasing office space in the surrounding suburbs. State government leaders (particularly governors William Cahill and Brendan Byrne) attempted to revitalize the downtown area by making it the center of state government. Between 1982 and 1992, more than a dozen office buildings were constructed primarily by the state to house state offices.[104] Today, Trenton's biggest employer is still the state of New Jersey. Each weekday, 20,000 state workers flood into the city from the surrounding suburbs.[105]

Notable businesses of the thousands based in Trenton include Italian Peoples Bakery, a wholesale and retail bakery established in 1936.[106] De Lorenzo's Tomato Pies and Papa's Tomato Pies were also fixtures of the city for many years, though both recently relocated to the suburbs.

Urban Enterprise Zone

editPortions of Trenton are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone. The city was selected in 1983 as one of the initial group of 10 zones chosen to participate in the program.[107] In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half of the 6+5⁄8% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[108] Established in January 1986, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in December 2023.[109]

The UEZ program in Trenton and four other original UEZ cities had been allowed to lapse as of January 1, 2017, after Governor Chris Christie, who called the program an "abject failure", vetoed a compromise bill that would have extended the status for two years.[110] In May 2018, Governor Phil Murphy signed a law that reinstated the program in these five cities and extended the expiration date in other zones.[111]

In 2018, the city had an average property tax bill of $3,274, the lowest in the county, compared to an average bill of $8,292 in Mercer County and $8,767 statewide.[112][113] The city had the sixth-highest property tax rate in New Jersey, with an equalized rate of 5.264% in 2020, compared to 2.760% in the county as a whole and a statewide average of 2.279%.[114]

Television market

editTrenton has long been part of the Philadelphia television market. After the 2000 United States census, Trenton was shifted from the Philadelphia metropolitan statistical area to the New York metropolitan statistical area. With a similar shift by the New Haven, Connecticut, area to the New York area, they were the first two cases where metropolitan statistical areas differed from their defined Nielsen television markets.[115]

Trenton was the site of the studios of the former public television station New Jersey Network.

Landmarks

edit- New Jersey State Museum – Combines a collection of archaeology and ethnography, fine art, cultural history and natural history.[116]

- New Jersey State House was originally constructed by Jonathan Doane in 1792, with major additions made in 1845, 1865 and 1871.[117]

- New Jersey State Library serves as a central resource for libraries across the state as well as serving the state legislature and government.[118]

- Trenton City Museum – Housed in the Italianate-style 1848 Ellarslie Mansion since 1978, the museum features artworks and other materials related to the city's history.[119]

- Trenton War Memorial – Completed in 1932 as a memorial to the war dead from Mercer County during World War I and owned and operated by the State of New Jersey, the building is home to a theater with 1,800 seats that reopened in 1999 after an extensive, five-year-long renovation project.[120]

- Old Barracks – Dating back to 1758 and the French and Indian War, the Barracks were constructed as a place to house British troops in lieu of housing the soldiers in the homes of area residents. The site was used by both the Continental Army and British forces during the Revolutionary War and stands as the last remaining colonial barracks in the state.[121]

- Trenton Battle Monument – Located in the heart of the Five Points neighborhood, the monument was built to commemorate the Continental Army's victory in the December 26, 1776, Battle of Trenton.[73] The monument was designed by John H. Duncan and features a statue of George Washington atop a pedestal that stands on a granite column 148 feet (45 m) in height.[122]

- Trenton City Hall – The building was constructed based on a 1907 design by architect Spencer Roberts and opened to the public in 1910. The council chambers stand two stories high and features a mural by Everett Shinn that highlights Trenton's industrial history.[123]

- William Trent House – Constructed in 1719 by William Trent, who the following year laid out what would become the city of Trenton, the house was owned by Governor Lewis Morris, who used the house as his official residence in the 1740s. Governor Philemon Dickerson used the home as his official residence in the 1830s, as did Rodman M. Price in the 1850s.[124]

- Adams and Sickles Building (added January 31, 1980, as #80002498) is a focal point for West End neighborhood, and is remembered for its soda fountain and corner druggist.[125]

- Friends Burying Ground, adjacent to the Trenton Friends Meeting House, is the burial site of several national and state political figures prominent in the city's early history.[126]

- Trenton Friends Meeting House (added April 30, 2008, as #08000362), dating back to 1739, it was occupied by the British Dragoons in 1776 and by the Continental Army later in the Revolutionary War.[127]

- Carver Center – formerly the Sunlight Elks Lodge, it was named after George Washington Carver, African-American agricultural scientist and inventor. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places for its significance in ethnic heritage - Black, from 1922 to 1975.[128]

- Old Masonic Temple - 1793 historic building put on the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing property to the State House Historic District.

-

The Trenton City Museum, located at the Ellarslie Mansion in Cadwalader Park

Sports

edit| Club | League | Venue | MLB affiliate | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trenton Thunder | MLB Draft League | Trenton Thunder Ballpark | None | 1994 | 5 |

Because of Trenton's near-equal distance to both New York City and Philadelphia, and because most homes in Mercer County receive network broadcasts from both cities, locals are sharply divided in fan loyalty between both cities. It is common to find Philadelphia's Phillies, Eagles, 76ers, Union and Flyers fans cheering (and arguing) right alongside fans of New York's Yankees, Mets, Nets, Knicks, Rangers, Islanders, Jets, Red Bulls and Giants or the New Jersey Devils.[129]

Between 1948 and 1979, Trenton Speedway, located in adjacent Hamilton Township, hosted world class auto racing. Drivers such as Jim Clark, A. J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, Al Unser, Bobby Unser, Richard Petty and Bobby Allison raced on the one-mile (1.6 km) asphalt oval and then re-configured 1+1⁄2-mile race track.[130] The speedway, which closed in 1980, was part of the larger New Jersey State Fairgrounds complex, which also closed in 1983. The former site of the speedway and fairgrounds is now the Grounds for Sculpture.[131]

The Trenton Thunder, minor league team owned by Joe Plumeri, plays at 6,341-seat Arm & Hammer Park, the stadium which Plumeri had previously named after his father in 1999.[132][133][134] The team was previously affiliated with the New York Yankees, Boston Red Sox, Detroit Tigers, and, before moving to Trenton, the Chicago White Sox, but became an unaffiliated collegiate summer baseball team of the MLB Draft League beginning in 2021.[135]

The Trenton Freedom of the Professional Indoor Football League were founded in 2013 and played their games at the Sun National Bank Center. The Freedom ended operations in 2015, joining the short-lived Trenton Steel (in 2011) and Trenton Lightning (in 2001) as indoor football teams that had brief operating lives at the arena.[136]

Parks and recreation

edit- Cadwalader Park – Trenton's largest city park covering 109.5 acres (44.3 ha), it was designed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who is most famous for designing New York City's Central Park.[137]

Government

editLocal government

editTrenton is governed within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under the Mayor-Council system of municipal government, one of 79 municipalities (of the 564) statewide that use this form of government.[138] The governing body is comprised of a mayor and a seven-member city council. Three city council members are elected at-large, and four come from each of four wards. The mayor and council members are elected concurrently on a non-partisan basis to four-year terms of office as part of the November general election.[8][139][140]

In October 2020, the city council overrode a mayoral veto and shifted municipal elections from May to November, with proponents citing the increased turnout and savings to the city of $180,000 in each election cycle. The mayor and members of council all had their term-end dates extended by six months and moved to December 31 from June 30, 2022.[141] The city retained a runoff provision that would have a December runoff in the event that the candidate with the highest number of votes does not obtain a majority.[142]

As of 2023[update], the mayor of Trenton is Reed Gusciora, whose term of office ends December 31, 2026; before taking office as mayor, Gusciora had served in the New Jersey General Assembly.[143] Members of the city council are Jasi Edwards (at-large), Crystal Feliciano (at-large), Teska Frisby (West Ward), Yazminelly Gonzalez (at-large), Joseph A. Harrison (East Ward), Jenna Figueroa Kettenburg (South Ward) and Jennifer Williams (North Ward).[4][144][145][146][147][148]

As they had not exceeded the minimum of 50 percent in the November 2022 general election, a run-off was held in December for the seats in the North and South Wards. Jennifer Williams won the North seat by a single vote against Algernon Ward,[149] which made Williams the first transgender individual to be elected to a city council position in New Jersey history as well as being the first LGBTQ+ city council member in Trenton history.[150] Jenna Figueroa Kettenburg won the South ward seat, defeating Damian G. Malave who had been ahead on Election Day but short of the cutoff, while a January 2023 runoff had Jasi Edwards, Crystal Feliciano and Yazminelly Gonzalez winning the three at-large seats.[146][147][151]

In February 2023, Judge William Anklowitz of the New Jersey Superior Court heard a case for election challenges in the North Ward runoff election for both candidates Algernon Ward and Jennifer Williams. Three of the ballots Ward contested were all rejected because they were mail-in ballots that were returned without the required inner envelope. The other rejection Ward challenged was a case involving a cure letter that a voter sent to the wrong place, leading to it being not counted. Williams contested one ballot that was not counted due to it having both a vote for Ward and for Williams. Judge Anklowitz determined that the slash through Ward's vote signaled the voter's intention to vote for Williams and thus determined the vote should have been counted. These election challenges were heard following a recount that was held that did not change the outcome of the vote. Jennifer Williams thus remained to hold her seat on Trenton City Council for the North Ward seat.[152]

In February 2022, the city council appointed Sonya Wilkins to fill the at-large seat expiring in December 2022 that had been held by Jerell A. Blakeley until he resigned from office the previous month to take a job outside the state.[153]

Mayor's conviction and removal from office

editOn February 7, 2014, Tony F. Mack and his brother, Raphiel, were convicted by a federal jury of bribery, fraud and extortion, based on the details of their participation in a scheme to take money in exchange for helping get approvals to develop a downtown parking garage as part of a sting operation by law enforcement.[154] Days after the conviction, the office of the New Jersey Attorney General filed motions to have Mack removed from office, as state law requires the removal of elected officials after convictions for corruption.[155] Initially, Mack fought the removal of him from the office but on February 26, a superior court judge ordered his removal and any actions taken by Mack between February 7 and the 26th could have been reversed by Muschal.[156] Previously, Mack's housing director quit after it was learned he had a theft conviction. His chief of staff was arrested trying to buy heroin. His half-brother, whose authority he elevated at the city water plant, was arrested on charges of stealing. His law director resigned after arguing with Mack over complying with open-records laws and potential violations of laws prohibiting city contracts to big campaign donors.[157]

From February 7 to July 1, 2014, the acting mayor was George Muschal who retroactively assumed the office on that date due to Mack's felony conviction, who had taken office on July 1, 2010.[158] Muschal, who was council president, was selected by the city council to serve as the interim mayor to finish the term.[156]

Federal, state, and county representation

editTrenton is located in the 12th Congressional District[159] and is part of New Jersey's 15th state legislative district.[160][161][162][163]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 12th congressional district is represented by Bonnie Watson Coleman (D, Ewing Township).[164][165] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[166] and George Helmy (Mountain Lakes, term ends 2024).[167][168]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 15th legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Shirley Turner (D, Lawrence Township) and in the General Assembly by Verlina Reynolds-Jackson (D, Trenton) and Anthony Verrelli (D, Hopewell Township).[169]

Mercer County is governed by a County Executive who oversees the day-to-day operations of the county and by a seven-member Board of County Commissioners that acts in a legislative capacity, setting policy. All officials are chosen at-large in partisan elections, with the executive serving a four-year term of office while the commissioners serve three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats up for election each year as part of the November general election.[170] As of 2024[update], the County Executive is Daniel R. Benson (D, Hamilton Township) whose term of office ends December 31, 2027.[171] Mercer County's Commissioners are:

Lucylle R. S. Walter (D, Ewing Township, 2026),[172] Chair John A. Cimino (D, Hamilton Township, 2026),[173] Samuel T. Frisby Sr. (D, Trenton, 2024),[174] Cathleen M. Lewis (D, Lawrence Township, 2025),[175] Vice Chair Kristin L. McLaughlin (D, Hopewell Township, 2024),[176] Nina D. Melker (D, Hamilton Township, 2025)[177] and Terrance Stokes (D, Ewing Township, 2024).[178][179][180]

Mercer County's constitutional officers are: Clerk Paula Sollami-Covello (D, Lawrence Township, 2025),[181][182] Sheriff John A. Kemler (D, Hamilton Township, 2026)[183][184] and Surrogate Diane Gerofsky (D, Lawrence Township, 2026).[185][186][187]

Politics

editAs of March 2011, there were a total of 37,407 registered voters in Trenton, of which 16,819 (45.0%) were registered as Democrats, 1,328 (3.6%) were registered as Republicans and 19,248 (51.5%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 12 voters registered to other parties.[188]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020[189] | 11.2% 2,443 | 88.2% 19,304 | 0.6% 146 |

| 2016[190] | 7.7% 1,715 | 90.6% 20,131 | 1.7% 379 |

| 2012[191] | 6.2% 1,528 | 93.4% 23,125 | 0.4% 97 |

| 2008[192] | 8.2% 2,157 | 89.9% 23,577 | 0.5% 141 |

| 2004[193] | 16.3% 3,791 | 79.8% 18,539 | 0.4% 146 |

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 93.4% of the vote (23,125 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 6.2% (1,528 votes), and other candidates with 0.4% (97 votes), among the 27,831 ballots cast by the city's 40,362 registered voters (3,081 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 69.0%.[191][194] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 89.9% of the vote here (23,577 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain with 8.2% (2,157 votes) and other candidates with 0.5% (141 votes), among the 26,229 ballots cast by the city's 41,005 registered voters, for a turnout of 64.0%.[192]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[195] | 10.7% 987 | 88.6% 8,120 | 0.7% 59 |

| 2017[196] | 8.6% 872 | 89.8% 9,128 | 1.7% 169 |

| 2013[197] | 24.7% 3,035 | 74.7% 9,179 | 0.7% 77 |

| 2009[198] | 12.4% 1,560 | 81.6% 10,235 | 3.5% 440 |

| 2005[199] | 15.3% 1,982 | 81.0% 10,484 | 3.6% 471 |

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 74.7% of the vote (9,179 cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 24.7% (3,035 votes), and other candidates with 0.6% (77 votes), among the 11,884 ballots cast by the city's 38,452 registered voters (407 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 30.9%.[197][200] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 81.6% of the vote here (10,235 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 12.4% (1,560 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 2.4% (305 votes) and other candidates with 1.1% (135 votes), among the 12,537 ballots cast by the city's 38,345 registered voters, yielding a 32.7% turnout.[198]

Fire department

editThe city of Trenton is protected on a full-time basis by the city of Trenton Fire and Emergency Services Department (TFD), which has been a paid department since 1892 after having been originally established in 1747 as a volunteer fire department.[201] The TFD operates out of seven fire stations and operates a fire apparatus fleet of 7 engine companies, 3 ladder companies and one rescue company, along with one HAZMAT unit, an air cascade unit, a mobile command unit, a foam unit, one fireboat, and numerous special, support and reserve units, under the command of two battalion chiefs and a deputy chief/tour commander each shift.[202][203]

Education

editColleges and universities

editTrenton is the home of two post-secondary institutions: Thomas Edison State University, serving adult students around the nation and worldwide[204] and Mercer County Community College's James Kerney Campus.[205]

The College of New Jersey, formerly named Trenton State College, was founded in Trenton in 1855 and is now located in nearby Ewing Township. Rider University was founded in Trenton in 1865 as The Trenton Business College. In 1959, Rider moved to its current location in nearby Lawrence Township.[206]

Public schools

editThe Trenton Public Schools serve students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade.[207] The district is one of 31 former Abbott districts statewide that were established pursuant to the decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court in Abbott v. Burke[208] which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[209][210] The district's board of education, comprised of seven members, sets policy and oversees the fiscal and educational operation of the district through its superintendent administration. As a Type I school district, the board's trustees are appointed by the mayor to serve three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats up for re-appointment each year. The board appoints a superintendent to oversee the district's day-to-day operations and a business administrator to supervise the business functions of the district.[211][212] The school district has undergone a 'construction' renaissance throughout the district.[citation needed]

As of the 2022–23 school year, the district, comprised of 25 schools, had an enrollment of 14,852 students and 966.4 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 15.4:1.[213] The district includes 13 elementary schools,[214] 6 intermediate schools,[215] three middle schools,[216] and three high schools.[217] They are as follows:

| Name | Grade(s) | Enrollment (2022–23)[218] |

|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood Learning Center | Pre-Kindergarten | N/A |

| Benjamin C. Gregory Elementary School | K–3rd | 269 |

| Benjamin Franklin Elementary School | 349 | |

| Cadwalader Elementary School | 163 | |

| Carroll Robbins Elementary School | 413 | |

| Darlene C. McKnight Elementary School[a] | 361 | |

| Dr. Crosby Copeland Elementary School[b] | 296 | |

| George Washington Elementary School | 289 | |

| Gershom Mott Elementary School | 357 | |

| Joseph Stokes Elementary School | 306 | |

| Luis Muñoz-Rivera Elementary School | 366 | |

| Patton J. Hill Elementary School | 502 | |

| Paul Robeson Elementary School | 341 | |

| William Harrison Elementary School | 239 | |

| Battle Monument Intermediate School | 4th–6th | 460 |

| Clara Parker Intermediate School | 515 | |

| Hedgepeth-Williams Intermediate School | 582 | |

| Joyce Kilmer Intermediate School | 498 | |

| Thomas Jefferson Intermediate School | 354 | |

| Ulysses S. Grant Intermediate School | 542 | |

| Arthur J. Holland Middle School | 7th–8th | 513 |

| Dr. MLK Jr. Middle School | 568 | |

| Grace A. Dunn Middle School | 670 | |

| Daylight/Twilight High School | 7th–12th | 479 |

| Trenton's Ninth Grade Academy | 9th | 796 |

| Trenton Central High School | 9th–12th | 2,255 |

Eighth-grade students from all of Mercer County are eligible to apply to attend the high school programs offered by the Mercer County Technical Schools, a county-wide vocational school district that offers full-time career and technical education at its Health Sciences Academy, STEM Academy and Academy of Culinary Arts, with no tuition charged to students for attendance.[219][220]

Marie H. Katzenbach School for the Deaf (previously New Jersey School for the Deaf and New Jersey State Institution for the Deaf and Dumb), the statewide school for the deaf, opened in Trenton in 1883 and was there until 1923, when it moved to West Trenton.[221]

Charter schools

editTrenton is home to several charter schools, including Capital Preparatory Charter High School, Emily Fisher Charter School, Foundation Academy Charter School, International Charter School, Paul Robeson Charter School and Village Charter School.[222]

The International Academy of Trenton, owned and monitored by the SABIS school network, became a charter school in 2014. On February 22, 2017, Trenton's mayor, Eric Jackson, visited the school when it opened its doors in the former Trenton Times building on 500 Perry Street, after completion of a $17 million renovation project. After receiving notice from the New Jersey Department of Education that the school's charter would not be renewed due to issues with academic performance and school management, the school closed its doors on June 30, 2018.[223]

Private schools

editTrenton Catholic Academy high school serves students in grades 9–12, while Trenton Catholic Academy grammar school serves students in Pre-K through 8th grade; both schools operate under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Trenton.[224]

Trenton is home to Al-Bayaan Academy, which opened for preschool students in September 2001 and added grades in subsequent years.[225]

Trenton Community Music School is a not-for-profit community school of the arts. The school was founded by executive director Marcia Wood in 1997. The school operates at Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church (on Tuesdays) and the Copeland Center for the Performing Arts (on Saturdays).

Crime

editThe Trenton Police Department was founded in 1792, when the city was incorporated. It works in conjunction with the Mercer County Sheriff's Office.[226]

In 2005, there were 31 homicides in Trenton, which at that time was the largest number in a single year in the city's history.[227] The city was named the 4th "Most Dangerous" in 2005 out of 129 cities with a population of 75,000 to 99,999 ranked nationwide in the 12th annual Morgan Quitno survey.[228] In the 2006 survey, Trenton was ranked as the 14th most dangerous city overall out of 371 cities included nationwide in the Morgan Quitno survey, and was again named as the fourth most dangerous municipality of 126 cities in the 75,000–99,999 population range.[229]

In September 2011, the city laid off 108 police officers due to budget cuts; this constituted almost one-third of the Trenton Police Department and required 30 senior officers to be sent out on patrols in lieu of supervisory duties.[230]

In 2013, the city set a new record with 37 homicides.[231] In 2014, there were 23 murders through the end of July and the city's homicide rate was on track to break the record set the previous year until an 81-day period when there were no murders in Trenton; the city ended the year with 34 murders.[232][233] In 2020, the city surpassed the 2013 homicide number with a record 40 homicides.[234]

New Jersey State Prison

editThe New Jersey State Prison (formerly Trenton State Prison) has two maximum security units. It houses some of the state's most dangerous individuals, which included New Jersey's death row population until the state banned capital punishment in 2007.[235]

The following is inscribed over the original entrance to the prison:

Labor, Silence, Penitence.

The Penitentiary House,

Erected By Legislative

Authority.

Richard Howell, Governor.

In The XXII Year Of

American Independence

MDCCXCVII

That Those Who Are Feared

For Their Crimes

May Learn To Fear The Laws

And Be Useful

Hic Labor, Hic Opus.[236]

Transportation

editRoads and highways

editAs of May 2010[update], the city had a total of 168.80 miles (271.66 km) of roadways, of which 145.57 miles (234.27 km) were maintained by the municipality, 11.33 miles (18.23 km) by Mercer County, 10.92 miles (17.57 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 0.99 miles (1.59 km) by the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission.[237]

Several highways pass through the city.[238] These include the Trenton Freeway (part of U.S. Route 1)[239] and the John Fitch Parkway, which is part of Route 29.[240] Canal Boulevard, more commonly known as Route 129, connects U.S. Route 1 and Route 29 in South Trenton.[241] U.S. Route 206,[242] Route 31[243] and Route 33[244] also pass through the city via regular city streets (Broad Street/Brunswick Avenue/Princeton Avenue, Pennington Avenue, and Greenwood Avenue, respectively).

Route 29 connects the city to Interstate 295 and Interstate 195, the latter providing a connection to the New Jersey Turnpike (Interstate 95) at Exit 7A in Robbinsville Township, although the section near downtown is planned to be converted to an urban boulevard.[245]

Public transportation

editPublic transportation within the city and to/from its nearby suburbs is provided in the form of local bus routes run by NJ Transit. SEPTA provides bus service to adjacent Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

The Trenton Transit Center, located on the heavily traveled Northeast Corridor, serves as the northbound terminus for SEPTA's Trenton Line (local train service to Philadelphia) and southbound terminus for NJ Transit Rail's Northeast Corridor Line (local train service to New York Penn Station). The train station also serves as the northbound terminus for the River Line, a diesel light rail line that runs to Camden.[246] Two additional River Line stops, Cass Street and Hamilton Avenue, are located within the city.[247]

Long-distance transportation is provided by Amtrak train service along the Northeast Corridor.[248]

The closest commercial airport is Trenton–Mercer Airport in Ewing Township, about 8 miles (13 km) from the center of Trenton, which has been served by Frontier Airlines offering service to and from 13 points nationwide.[249]

Other nearby major airports are Newark Liberty International Airport and Philadelphia International Airport, located 55.2 miles (88.8 km) and 43.4 miles (69.8 km) away, respectively, and reachable by direct New Jersey Transit or Amtrak rail link (to Newark) and by SEPTA Regional Rail (to Philadelphia).

NJ Transit Bus Operations provides bus service between Trenton and Philadelphia on the 409 route, with service to surrounding communities on the 600, 601, 603, 606, 607, 608, 609, 611 and 624 routes.[250][251]

The Greater Mercer Transportation Management Association offers service on the Route 130 Connection between the Trenton Transit Center and the South Brunswick warehouse district with stops along the route including Hamilton train station, Hamilton Marketplace, Hightstown and East Windsor Town Center Plaza.[252]

Media

editTrenton is served by two daily newspapers, The Times and The Trentonian, and a monthly advertising magazine, "The City" Trenton N.E.W.S.. Radio station WKXW and Top 40 WPST are also licensed to Trenton. Defunct periodicals include the Trenton True American. A local television station, WPHY-CD TV-25, serves the Trenton area.[253]

Trenton is officially part of the Philadelphia television market but some local pay TV operators also carry stations serving the New York City market. While it is its own radio market, many Philadelphia and New York stations are easily receivable.

Notable people

editSee also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Kuperinsky, Amy. "'The Jewel of the Meadowlands'?: N.J.'s best, worst and weirdest town slogans" Archived November 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, January 22, 2015. Accessed July 12, 2016. "Trenton. There are scant few unfamiliar with the huge neon sign installed in 1935 that sits on the Lower Trenton Bridge, declaring 'Trenton Makes, The World Takes.' Lumber company owner S. Roy Heath came up with the slogan, originally 'The World Takes, Trenton Makes,' for a chamber of commerce contest in 1910."

- ^ a b c d e 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places Archived March 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990 Archived August 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Trenton City Council Chambers Archived August 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Trenton, New Jersey. Accessed February 2, 2023. No members are listed as of date accessed

- ^ 2023 New Jersey Mayors Directory Archived March 11, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, updated February 8, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023.

- ^ Administration & Finance Department Archived October 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, City of Trenton. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- ^ City Clerk Archived August 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, City of Trenton. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- ^ a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 73.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020-2021 Archived June 29, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 2, 2023.

- ^ List of 2020 Census Urban Areas Archived December 29, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau.Accessed January 2, 2023.

- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f QuickFacts Trenton city, New Jersey Archived October 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities Archived February 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2022 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022 Archived July 17, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau, released May 2023. Accessed May 18, 2023. Note that townships (including Edison, Lakewood and Woodbridge, all of which have larger populations) are excluded from these rankings.

- ^ a b Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021 Archived March 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for Trenton, NJ Archived November 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Postal Service. Accessed January 10, 2012.

- ^ Zip Codes Archived June 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed September 7, 2013.

- ^ Area Code Lookup – NPA NXX for Trenton, NJ Archived June 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Area-Codes.com. Accessed September 7, 2013.

- ^ U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey Archived November 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ New Jersey County Map Archived March 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed July 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Parker, L.A. "City celebrating role as U.S. capital in 1784" Archived September 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Trentonian, November 6, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2012. "City and state leaders kicked off a two-month celebration yesterday with a news conference highlighting Trenton's brief role as the capital of the United States in 1784."

- ^ a b New Jersey: 2020 Core Based Statistical Areas and Counties Archived April 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 22, 2022.

- ^ "Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas." Archived April 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Office of Management and Budget Bulletin 13-01, February 28, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2019.

- ^ Table1. New Jersey Counties and Most Populous Cities and Townships: 2020 and 2010 Censuses Archived February 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1 – Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Trenton city, Mercer County, New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 10, 2012.

- ^ a b Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Trenton city Archived May 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed January 10, 2012.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010 Archived June 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to Trenton, New Jersey Trenton Transit District Plans Trenton Transit District Development Project". Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

As the only city in New Jersey to serve three major railway systems (Amtrak, NJ Transit, and SEPTA), with service to New York and Philadelphia, Trenton has untapped potential to support dense, walkable, and mixed-use development near the City's transit stations.

- ^ a b c d Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606–1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. pp. 164–165. Accessed May 30, 2024.

- ^ County History Archived July 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Hunterdon County, New Jersey. Accessed April 18, 2011.

- ^ a b National Archives: Post Office Commissions to Abraham Hunt, 10 January 1764

- ^ a b Schuyler, 1929, p. 132

- ^ Honeyman, Abraham Van Doren. Index-analysis of the Statutes of New Jersey, 1896–1909: Together with References to All Acts, and Parts of Acts, in the 'General Statutes' and Pamphlet Laws Expressly Repealed: and the Statutory Crimes of New Jersey During the Same Period Archived October 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 302. New Jersey Law Journal Publishing Company, 1910. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- ^ "Before There Was Trenton: A 350th Anniversary Look at the 17th Century Display of Early New Netherland Colonial Artifacts June 22 – October 19, 2014" Archived September 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Trenton City Museum, October 12, 2014. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- ^ Ricky, Donald B. (1999). Indians of Maryland. St. Clair Shoes, MI: Somerset. p. 72. ISBN 9780403098774.

- ^ Hunter, Richard. "Chapter 4: Land Use History" Archived June 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, from Abbott Farm National Historic Landmark Interpretive Plan, Mercer County, New Jersey. Accessed May 5, 2016.

- ^ Krystal, Becky. "Trenton, N.J.: One for the history buffs" Archived October 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, February 10, 2011. Accessed January 10, 2012. "Back in the early 18th century, at least, the area was remote enough for Trent, a wealthy Philadelphia merchant, to build his summer home there near the banks of the Delaware River. And though it's dwarfed by its modern-day neighbors, at the time the home reflected its owner's 'ostentatious nature,' Nedoresow said. Further stroking his ego, he named the settlement he laid out 'Trent-towne,' which eventually evolved into the current moniker."

- ^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names Archived November 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- ^ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 304. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- ^ a b "History of Trenton | Trenton, NJ". www.trentonnj.org. Archived from the original on November 16, 2023. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ "This Day in History – Dec 26, 1776: Washington wins first major U.S. victory at Trenton" Archived January 28, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, History, November 13, 2009, updated July 27, 2019. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (2006). "The Bridge. Assunpink, The Most Awful Moment". Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 290–307. ISBN 0-19-518159-X. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ Messler, Mary J. "Chapter IV: Some Notable Events of Post-Revolutionary Times" Archived February 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine from A History of Trenton: 1679–1929, Trenton Historical Society. Accessed May 5, 2016. "The question now resolved itself into a quarrel between the North and the South. New England favored Trenton, whereas the Southern States felt that in the selection of any site north of Mason and Dixon's line their claims for recognition were being slighted, and their interests sacrificed to New England's commercialism."

- ^ Stryker, William S. (1882). Washington's reception by the people of New Jersey in 1789. Trenton, New Jersey. p. 4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Trenton New Jersey, United States Archived March 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed November 19, 2023.

- ^ A Short History of New Jersey Archived January 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey. Accessed January 10, 2012.

- ^ Messler, Mary. "Some Notable Events of Post-Revolutionary Times". trentonhistory.org. Trenton Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ Some of Trenton's History Archived October 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, City of Trenton. Accessed October 12, 2015. "During the 1812 War, the primary hospital facility for the U.S. Army was at a temporary location on Broad Street."

- ^ Richman, Steven M. Reconsidering Trenton: The Small City in the Post-Industrial Age Archived October 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 49. McFarland & Company, 2010. ISBN 9780786462230. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- ^ Blackwell, John|. "1948: A cry for justice" Archived December 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Trentonian. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- ^ Schlegel, Sharon. "Harrowing case of the 'Trenton Six'" Archived August 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Times, January 28, 2012. Accessed June 4, 2018. "The recently published story of the 'Trenton Six,' dramatically told in Cathy Knepper's newest book, Jersey Justice: The Story of the Trenton Six, is so filled with proven instances of injustice that it is almost hard to believe.... Reading how the men were arrested randomly and haphazardly (despite a partial witness claiming they were not the perpetrators) is horrifying. Equally upsetting is that they were held incommunicado for days without warrants, abused and drugged into confessing."

- ^ Chapter 7 Riverfront District Downtown Capital District Master Plan Trenton, New Jersey Archived November 16, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, City of Trenton. Accessed November 19, 2023.

- ^ Cumbler, John T. A Social History of Economic Decline: Business, Politics and Work in Trenton Archived October 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 283. Rutgers University Press, 1989. ISBN 9780813513744. Accessed February 12, 2014.

- ^ Listokin, David; and Listokin, Barbara. Barriers to the Rehabilitation of Afordable Housing Volume II Case Studies Archived October 18, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, May 2001. Accessed December 1, 2019. "Socioeconomic and housing challenges are especially severe in some of Trenton’s oldest neighborhoods. In the Old Trenton area, abandonment went unchecked for decades, and when abandoned houses were demolished by the city, the empty lots remaining would fill with garbage and vermin. Another hard-hit location was the 'Battle Monument' area: 'Time has not been kind to the Battle Monument section of this city. The five-block area, the hub of the Battle of Trenton in 1775 and of transportation in the 1950s, has in the last four decades suffered from abandonment and neglect.'"

- ^ The 10 Least Populated State Capitals Archived August 23, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, World Atlas. Accessed August 23, 2023. "Annapolis, Maryland, the 8th smallest state capital by population is also the smallest state capital in size with an area of 6.73 square miles. Other small capitals include Trenton, New Jersey (7.66 sq mi); Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (8.11 sq mi); and Montpelier, Vermont (10.2 sq mi)."

- ^ Discover Our Bridges Archived December 31, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- ^ Trenton-Morrisville (Rt. 1) Toll Bridge Archived December 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission. Accessed December 1, 2019. "The Trenton-Morrisville Toll Bridge carries U.S. Route 1 over the Delaware River between Trenton, New Jersey and Morrisville, Pennsylvania.... The bridge is a twelve-span, simply supported composite steel girder and concrete deck structure with an overall length of 1,324 feet."

- ^ Lower Trenton Toll-Supported Bridge Archived November 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission. Accessed December 1, 2019. "The Lower Trenton Toll-Supported Bridge, also known as the 'Trenton Makes The World Takes Bridge,' connects Warren Street in Trenton, N.J. with East Bridge Street in Morrisville, Pa. -- one of three bridges connecting the two communities.... The current 1,022-foot bridge is a five-span Warren Truss built in 1928."

- ^ Calhoun Street Toll-Supported Bridge Archived December 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission. Accessed December 1, 2019. "The Calhoun Street Toll-Supported Bridge is the oldest bridge structure owned and operated by the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission. It turned 125 years old on October 20, 2009.... Of the 20 bridges in the DRJTBC system, the Calhoun Street Toll-Supported Bridge is the only one made of wrought iron. A Phoenix Pratt truss with a total length of 1,274 feet, it also holds the distinction as the Commission’s longest through-truss bridge and the Commission’s only seven-span truss bridge."

- ^ Science In Your Backyard: New Jersey Archived August 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, United States Geological Survey. Accessed October 28, 2014.

- ^ Stirling, Stephen. "U.S. Census shows East Brunswick as statistical center of N.J." Archived June 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, March 31, 2011. Accessed May 21, 2017. "The state's geographic center remains Hamilton Township in Mercer County, just southeast of Trenton."

- ^ Weiss, Daniel. "North/South Skirmishes; A film tries to draw the line between North and South Jersey." Archived June 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Monthly, April 30, 2008. Accessed June 12, 2018.

- ^ Howe, Randy. Nifty 50 States Brainiac, p. 1159. Kaplan Publishing, 2008. ISBN 9781427797117. Accessed February 12, 2014. "Carson City is one of just two capital cities in the United States that borders another state; the other is Trenton, New Jersey."

- ^ Areas touching Trenton Archived August 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, MapIt. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- ^ Municipalities within Mercer County, NJ Archived November 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- ^ New Jersey Municipal Boundaries Archived December 4, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- ^ Di Ionno, Mark. "Chambersburg" Archived July 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Star-Ledger, July 17, 2007. Accessed March 16, 2012. "The difference between Chambersburg, the traditional Italian section of Trenton, and other city neighborhoods that have undergone 'natural progression' is that Chambersburg hung on so long."

- ^ Richard Grubb & Associates. Three Centuries of African-American History in Trenton: A Preliminary Inventory of Historic Sites Archived December 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Trenton Historic Society, September 2011. Accessed December 1, 2019. "Shiloh Baptist Church is the city’s oldest African-American Baptist congregation. The first groups of Black Baptists were formed in the city around 1880, with Shiloh formally organized in 1896."

- ^ a b Trenton Battle Monument Archived July 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Division of Parks and Forestry. Accessed September 7, 2013.

- ^ "In their own words, South Ward candidates explain why they should win City Council seat" Archived June 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Trentonian, October 18, 2009. Accessed June 12, 2018.

- ^ Locality Search Archived July 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Interactive United States Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification Map". plantmaps.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Station: Trenton Mercer CO AP, NJ". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Staff. "Heat sets new record high in Trenton at 106 degrees" Archived February 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Trentonian, July 22, 2011. Accessed February 12, 2014. "The thermometer reached a record-setting 106 degrees here in the City of Trenton, easily smashing July 22nd's previous high mark from 1926, when the temp reached 101 degrees."

- ^ a b c d "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map Archived July 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Agriculture. Accessed November 26, 2019.

- ^ "City of Trenton, New Jersey Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan" Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, City of Trenton. Accessed February 12, 2014.

- ^ City of Trenton, New Jersey Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, City of Trenton, adopted June 19, 2008. Accessed June 12, 2018. "The average snowfall is 24.9 inches, but has ranged from as low as 2 inches (in the winter of 1918–1919) to as high as 76.5 inches (in 1995–1996). The heaviest snowstorm on record was the Blizzard of 1996 on January 7–8, 1996, when 24.2 inches buried the city."

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 12, 2021.