Hauser Dam (also known as Hauser Lake Dam) is a hydroelectric straight gravity dam on the Missouri River about 14 miles (23 km) northeast of Helena, Montana, in the United States. The original dam, built between 1905 and 1907, failed in 1908 and caused severe flooding and damage downstream. A second dam was built on the site in 1908 and opened in 1911 and comprises the present structure. The current Hauser Dam is 700 feet (210 m) long and 80 feet (24 m) high.[4] The reservoir formed by the dam, Hauser Lake (also known as Hauser Reservoir), is 25 miles (40 km) long, has a surface area of 3,800 acres (1,500 ha), and has a storage capacity of 98,000 acre-feet (121,000,000 m3) of water when full.[5]

| Hauser Dam | |

|---|---|

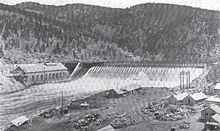

Hauser Dam in late 1908 during its reconstruction. | |

| Official name | Hauser Dam |

| Location | Lewis and Clark County, Montana, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 46°45′55″N 111°53′13″W / 46.76528°N 111.88694°W |

| Construction began | 1905 (first dam); 1908 (second dam) |

| Opening date | 1907 (first dam); 1911 (second dam) |

| Operator(s) | NorthWestern Corporation |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Missouri River |

| Height | 80 feet (24 m) (second dam) |

| Length | 700 feet (210 m) (second dam) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Hauser Lake |

| Normal elevation | 3,655 ft (1,114 m)[1] |

| Power Station | |

| Installed capacity | 17.7 MW[2] |

| Annual generation | 135.34 GWh (2009)[3] |

| Power transmission: 69 kV single-circuit | |

The dam is a "run-of-the-river" dam because it can generate electricity without needing to store additional water supplies behind the dam. The powerhouse contains six generators, bringing Hauser dam's generating capacity to 17 MW.

History

editConstruction of first dam

editThe first Hauser Dam was built by the Missouri River Power Company and its successor, the United Missouri River Power Company. Samuel Thomas Hauser, a former Territorial Governor of Montana from 1885 to 1887, enjoyed a lengthy career in banking, mining, railroads, ranching, and smelting, but encountered a series of financial setbacks after the Panic of 1893 which nearly ruined him financially.[6][7] In his early 60s, Hauser began to rebuild his finances by branching out into the relatively new industry of hydroelectric power generation.[7] In 1894, he formed the Missouri River Power Company, and won the approval of the United States Congress to build a dam (Hauser Dam) 2 miles (3.2 km) below Stubbs' Ferry. In 1905, Hauser and other directors of the Missouri River Power Company formed the Helena Power Transmission Company (also known as the "Helena Power and Transmission Company").[8] The two companies merged on February 16, 1906, to form the United Missouri River Power Company.[9]

The dam was named for Samuel T. Hauser.[10] Hauser Dam was a steel dam built on masonry footings on top of gravel, with the ends of the dam anchored in bedrock on either side of the river.[11][12] The Wisconsin Bridge and Iron Company constructed the dam for the power company.[10] J.F. Jackson, a Wisconsin Bridge and Iron engineer, designed the structure.[13] Martin Gerry supervised the construction for the power company.[14] Gerry and Wisconsin Bridge engineer James McKittrick argued several times over the dam's design, and Gerry ordered a number of changes to the dam to strengthen it.[14] Jackson's design had to overcome a significant engineering problem: bedrock lay out of reach under the riverbed, covered by a thick layer of gravel. To overcome the fact that 300 feet (91 m) of the center section of the dam was built on a gravel riverbed and the rest on bedrock,[13] sheet pilings (supplied by the L. P. Friestedt Company of Chicago, which had a patented steel sheet piling system) were driven 35 feet (11 m) into the riverbed and the steel of the dam attached to the pilings.[13][15] The pilings were set at an angle of 1.5:1 to discourage sliding, and a triangular masonry footing capped with concrete on the upstream side set against the pilings in the riverbed to support the dam.[13] The upstream face of the dam was covered in concrete, and a 20-foot (6.1 m) deep layer of volcanic ash laid down on the upstream riverbed extending 300 feet (91 m) from the dam to discourage seeping.[13] Volcanic ash is very fine, and Jackson trusted that the weight of the water above the ash blanket would compact it to the point of being impenetrable, thus preventing water from eroding the gravel around the pilings.[16] The dam was 630 feet (190 m) long and 75 feet (23 m) high.[13][17] The spillway was 500 feet (150 m) wide and 13 feet (4.0 m) deep.[13] The 10 horizontal turbines in the powerhouse delivered 14,000 kilowatts of power.[18] The total cost of the dam at that time was $1.5 million.[19] The United Missouri Power declared Hauser Dam operational on February 12, 1907.[11]

Collapse of first dam

editOn April 14, 1908, at about 2:30 p.m., Hauser Dam failed after water pressure undermined the masonry footings (the steel dam itself being structurally sound).[11][12][13][20] The first sign of trouble was when silt-heavy water began gushing from the base of the dam near the powerhouse.[13][14] A power company employee, spotting the problem, ran into the powerhouse and told everyone to flee for their lives.[14] About 15 minutes later, the masonry footings gave way, causing the upstream section of the dam to settle and a 30-foot-wide (9 m) breach to open in the dam.[14][21] The water pouring through the breach further undermined the dam's footing, and six minutes later a 300-foot-wide (91 m) section of the dam tore loose.[14][21] The powerhouse was only slightly damaged.[21] A surge of water 25 to 30 feet (7.6 to 9.1 m) high swept downstream.[22] The remaining sections of the dam, anchored to bedrock, helped hold back some of the water for a time, reducing the destructiveness of the flood.[23] In the state capital of Helena at the time, Gerry received a telephone call from the dam operators alerting him to the dam's destruction.[23] He immediately sent telegrams to all towns and cities downstream, warning them of the coming flood.[23] A Great Northern Railway locomotive was dispatched to the city of Great Falls, 70 miles (110 km) downstream, warning stations along the way about the dam break.[23]

The warnings and the geology of the Missouri River below Hauser Dam helped save numerous lives. The construction camp at Holter Dam (then being built) was swept away.[21] Future motion picture actor Gary Cooper and his family, living at the Seven Bar Nine Ranch, were notified in time and evacuated before the floodwaters tore across a portion of their property.[24] The flood reached the small town of Craig, Montana, around 7:00 p.m., but the narrow canyons of the Missouri River above the town helped hold back part of the floodwaters and dissipated much of their energy.[14] The residents of the town received plenty of warning, and were evacuated.[14] At first, the press reported that the town had been swept away,[21] but this proved inaccurate as only a few shacks and the railroad station were uprooted.[14] The famous iron Craig Bridge (normally 25 feet [7.6 m] above water) had more than 2 feet (1 m) of water over its deck and was feared doomed, but it held.[21][25] The Great Northern Railway tracks from Craig to Ulm, Montana, were under water.[21] Workers at the Boston and Montana Smelter in Great Falls improvised a wing dam to deflect the floodwaters away from the smelter site and dynamited a portion of Black Eagle Dam to allow the floodwaters to go downstream.[21] Their efforts were not needed, as the Missouri River only rose 7 feet (2.1 m) by the time it reached that city.[14] Nonetheless, damages were estimated at more than $1 million.[21][23] At the end of the 20th century, pieces of the steel dam could still be found on the banks of the Missouri River.[14]

The collapse of the dam affected the way engineers design dams. The first Hauser Dam was one of only three steel dams in the world (the others being Ashfork-Bainbridge Steel Dam and Redridge Steel Dam). At the turn of the twentieth century, many engineers argued for the use of steel as a primary dam-building material. Steel had many advantages: it was not only cheaper, but also lighter, more easily transported, and more watertight than traditional materials like concrete, timber, stone, or earth. Furthermore, the use of steel simplified design calculations because standards and tolerances could be monitored at the steel mill. However, because steel dams appeared fragile to the eye, many opposed them in spite of the advantages. After Hauser Dam's collapse, opponents of steel won out. Even though the washout was the fault of too-short pilings—not the fault of steel—engineers rejected steel as a dam-building material, and no other steel dam has ever been built.[26]

Second dam

editUnited Missouri River Power began reconstruction of Hauser Dam in July 1908, completing it in the spring of 1911.[11] The Foundation Company of New York rebuilt the dam.[27] Jesse Baker Snow, a noted engineer from New York, was the engineer and assistant superintendent for the dam's reconstruction.[27]

The current Hauser Dam has four sections: An overflow spillway, abutments on either side of the overflow spillway, a non-spillover section east of the left abutment (below which is the powerhouse), and a 32-foot (9.8 m) deep forebay which impounds water behind the powerhouse.[4] The spillway is 493 feet (150 m) long.[4] Five hydraulic sliding gates and 17 manually operated flashboards allow water to overflow the dam.[4][28] Hauser Dam can only generate 17 megawatts of power, and so requires little water to function.[4]

This section needs to be updated. (May 2024) |

In 2015 NorthWestern began removing and refurbishing the original 1911 turbines. They expect to refurbish one of the six pairs of turbines each year.[29]

Hauser Lake

editThe reservoir formed by Hauser Dam is 15.5 miles (24.9 km) in length and only 0.1 miles (0.16 km) to 1.1 miles (1.8 km) in width.[30] The lake has a surface area of 3,800 acres (1,500 ha), and has a storage capacity of 98,000 acre-feet (121,000,000 m3) of water when full.[5] Hauser Lake has a mean depth of 26 feet (7.9 m) and a maximum depth of 70 feet (21 m).[31]

The creation of Hauser Lake led to the creation of nearby Lake Helena. The water impounded by Hauser Dam inundated the lower portion of Prickly Pear Creek, causing the formation of Lake Helena.[30] A narrow canyon 3.9 miles (6.3 km) in length filled with deep water (known as the Causeway Arm) connects Hauser Lake with Lake Helena.[30] Lake Helena is extremely shallow and develops dense amounts of aquatic vegetation, making it an important nesting, stopover, and feeding area for birds.[30]

The distance from Hauser Dam to Holter Reservoir, the next lake downstream, is 4.6 miles (7.4 km).[30] There are several recreation areas along the lake, such as White Sandy Recreation area and Black Sandy State Park.[32][33]

Fishing

editThe lake commonly yields rainbow and brown trout, walleye and perch. It is an extremely popular weekend fishing spot. The lake is regularly stocked with fish.[34]

| Species | Family | Class | Native to MT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brook Trout | Trout | Coldwater | Introduced |

| Brown Trout | Trout | Coldwater | Introduced |

| Burbot | Codfish | Coldwater | Native |

| Common Carp | Minnow | Warmwater | Introduced |

| Fathead Minnow | Minnow | Warmwater | Native |

| Kokanee | Trout | Coldwater | Introduced |

| Longnose Sucker | Sucker | Warmwater | Native |

| Mottled Sculpin | Sculpin | Native | |

| Mountain Whitefish | Trout | Coldwater | Native |

| Rainbow Trout | Trout | Coldwater | Introduced |

| Smallmouth Buffalo | Sucker | Warmwater | Native |

| Utah Chub | Minnow | Introduced | |

| Walleye | Perch | Warmwater | Introduced |

| Westslope Cutthroat Trout | Trout | Coldwater | Native |

| White Sucker | Sucker | Warmwater | Native |

| Yellow Perch | Perch | Warmwater | Introduced |

Dam ownership and access

editCost overruns on downstream Holter Dam, waning investor enthusiasm, and the liability associated with the collapse of the first Hauser Dam nearly drove Samuel Hauser (United Missouri's largest shareholder) into bankruptcy.[35][36] Hauser sold his interest in United Missouri River Power to John D. Ryan, who on October 25, 1912, merged United Missouri River Power with the Butte Electric and Power Company, Billings and Eastern Montana Power Company, and Madison River Power Company to form the Montana Power Company.[36][37][38] Montana Power took over not only United Missouri's Canyon Ferry Dam and Hauser Dam but the partially built Holter Dam as well.[38]

On November 2, 1999, Montana Power announced it was selling all of its dams and other electric power generating plants to PPL Corporation for $1.6 billion.[39] The sale was expected to generate $30 million in taxes for the state of Montana (although MPC said the total would be lower).[40] In November 2001, citizens of Montana upset with energy price increases announced by PPL sought passage of a ballot initiative that would require the state of Montana to buy all of PPL's hydroelectric dams, including Hauser Dam.[41] Montana voters rejected the initiative in November 2002.[42]

In September 2013, NorthWestern Energy, an energy company based in Sioux Falls, South Dakota and operating in South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana, announced that it would purchase from PPL Montana 11 hydroelectric facilities in Montana, including Hauser Dam.[43] The Montana Public Service Commission approved the deal in September 2014 and the two companies completed the $890 million purchase in November 2014.[44]

Footnotes

edit- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hauser Dam

- ^ "Century of service: Turbines at Hauser Dam to be removed for refurbishing". Independent Record. 4 April 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Hauser". Carbon Monitoring for Action. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ a b c d e Upper Missouri River Reservoir Fisheries Management Plan, 2010–2019, Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, May 13, 2010, p. 11.

- ^ a b Upper Missouri River Reservoir Fisheries Management Plan, 2010–2019, Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, May 13, 2010, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ Goodspeed, The Province and the States..., 1904, pp. 452–454.

- ^ a b Shearer, Louisiana to Ohio, 2004, p. 708.

- ^ King, "Annual Address," Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies, March 1906, p. 103.

- ^ Murphy, The Comical History of Montana: A Serious Story for Free People, 1912, p. 267.

- ^ a b Aarstad, et al., Montana Place Names From Alzada to Zortman, 2009, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d Hall, Montana, 1912, p. 135.

- ^ a b Jackson, Dams, 1997, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wegmann, The Design and Construction of Dams, 1918, p. 298.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Axline, "Hauser Dam," METNet.MT.gov, no date.

- ^ Sheet pilings are long sections of structural steel which interlock vertically to form a continuous wall.

- ^ Parrett 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Smith, "The Hauser Lake and Wolf Creek Projects," Stone & Webster Public Service Journal, October 1908, p. 236.

- ^ Smith, "The Hauser Lake and Wolf Creek Projects," Stone & Webster Public Service Journal, October 1908, p. 236-237.

- ^ Harts, "Discussion: Forests and Reservoirs in Their Relation to Stream Flow With Particular Reference to Navigable Rivers," Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, March 1909, p. 356.

- ^ Terzaghi, Peck, and Mesri, Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice, 1996, p. 478.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Two Towns Swept By Montana Flood," The New York Times, April 16, 1908.

- ^ "Dam Bursts in Montana," The New York Times, April 15, 1908.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, "The Hauser Lake and Wolf Creek Projects," Stone & Webster Public Service Journal, October 1908, p. 237.

- ^ Swindell, The Last Hero: A Biography of Gary Cooper, 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Axline, Conveniences Sorely Needed: Montana's Historic Highway Bridges, 1860–1956, 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Parrett 2009, p. 33.

- ^ a b "J.B. Snow, 79, Dead," The New York Times, June 18, 1947.

- ^ Flashboards are a system of wooden or metal panels which can be raised or lowered to allow excess water to pass over the crest of the dam. A series of metal frames holds the flashboards in place. Placing more than one flashboard on top of the other allows the dam's height to be temporarily raised. Raising the flashboard can permit water to pass beneath the flashboard and over the dam, alleviating stress on the dam. The higher the flashboard is raised, the more water passed beneath and over the dam.

- ^ AL KNAUBER (April 4, 2015). "Century of service: Turbines at Hauser Dam to be removed for refurbishing". Helena Independent Record.

- ^ a b c d e Upper Missouri River Reservoir Fisheries Management Plan, 2010–2019, Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, May 13, 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Upper Missouri River Reservoir Fisheries Management Plan, 2010–2019, Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, May 13, 2010, p. 7.

- ^ "White Sandy Recreation Site". Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on 2012-06-01. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ "Black Sandy, State Park on Hauser Lake". Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ "FISHMT :: Waterbody Details". myfwp.mt.gov. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ Johnson, Lon (November 1994). "Holter Hydroelectric Facility, House No. 8" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. 2. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Clary, Lewis & Clark on the Upper Missouri, 1999, p. 137.

- ^ Aarstad, et al., Montana Place Names From Alzada to Zortman, 2009, p. 125.

- ^ a b Malone, The Battle for Butte: Mining and Politics on the Northern Frontier, 1864–1906, 2006, p. 204.

- ^ Dennison, "A New Plan for Holter Dam Repairs," Great Falls Tribune, May 25, 2000; Johnson, "MPC to Sell Power Plants," The Missoulian, December 10, 1997; Anez, "PP&L Global Buying Montana Power Plants for $1.6 Billion," Associated Press, November 2, 1998.

- ^ "MPC Casts Doubt on $30 Million Tax Payment on Dam Sales," Associated Press, March 3, 1999.

- ^ Gallagher, "Drive to Buy Montana Hydroelectric Dams Announced," Associated Press, November 20, 2001.

- ^ Berg, "Montanans Reject Buying PPL Dams," Allentown Morning Call, November 7, 2002.

- ^ "A Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity for Montana: PPL Hydro Acquisition" (PDF). NorthWestern Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Black, Jo Dee (18 November 2014). "Montana hydro dams sale to NorthWestern Energy complete". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

Bibliography

edit- Aarstad, Rich; Arguimbau, Ellen; Baumler, Ellen; Porsild, Charlene L.; and Shovers, Brian. Montana Place Names From Alzada to Zortman. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press Press, 2009.

- Anez, Bob. "PP&L Global Buying Montana Power Plants for $1.6 Billion." Associated Press. November 2, 1998.

- Axline, Jon. Conveniences Sorely Needed: Montana's Historic Highway Bridges, 1860–1956. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press, 2005.

- Axline, Jon. "Hauser Dam." METNet.MT.gov. No date. Accessed 2010-06-15.

- Berg, Christian. "Montanans Reject Buying PPL Dams." Allentown Morning Call. November 7, 2002.

- Clary, Jean. Lewis & Clark on the Upper Missouri. Stevensville, Mont.: Stoneydale Press Publishing Co., 1999.

- "Dam Bursts in Montana." The New York Times. April 15, 1908.

- Dennison, Mike. "A New Plan for Holter Dam Repairs." Great Falls Tribune. May 25, 2000.

- "Fishing Access to All PPL Dams in Montana Now Prohibited." Associated Press. May 9, 2003.

- Gallagher, Susan. "Drive to Buy Montana Hydroelectric Dams Announced." Associated Press. November 20, 2001.

- Goodspeed, Weston Arthur. The Province and the States, A History of the Province of Louisiana Under France and Spain, and of the Territories and States of the United States Formed Therefrom. Madison, Wisc.: Weston Historical Association, 1904.

- Hall, J. H. Montana. Helena, Mont.: Independent Publishing Co., 1912.

- Harts, William W. "Discussion: Forests and Reservoirs in Their Relation to Stream Flow With Particular Reference to Navigable Rivers." Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. March 1909.

- Johnson, Lon (November 1994). "Holter Hydroelectric Facility, House No. 8" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. 2. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- "J. B. Snow, 79, Dead." The New York Times. June 18, 1947.

- Jackson, Donald C. Dams. Brookfield, Vt.: Ashgate, 1997.

- Johnson, Charles S. "MPC to Sell Power Plants." The Missoulian. December 10, 1997.

- King, Ernest W. "Annual Address." Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies. March 1906.

- Malone, Michael P. The Battle for Butte: Mining and Politics on the Northern Frontier, 1864–1906. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

- "MPC Casts Doubt on $30 Million Tax Payment on Dam Sales." Associated Press. March 3, 1999.

- Murphy, Jerre C. The Comical History of Montana: A Serious Story for Free People. San Diego: E.L. Scofield, 1912.

- Parrett, Aaron. "'The Huge Mass Writhed and Screamed like a Live Thing': Revisiting the Failure of Hauser Dam." Montana The Magazine of Western History. 59, 4 (Winter 2009): 24–45.

- Robbins, Chuck. Flyfisher's Guide to Montana. Belgrade, Mont.: Wilderness Adventures Press, 2005.

- Shearer, Benjamin F. Louisiana to Ohio. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2004.

- Smith, Barrett. "The Hauser Lake and Wolf Creek Projects." Stone & Webster Public Service Journal. October 1908.

- Swindell, Larry. The Last Hero: A Biography of Gary Cooper. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1980.

- Terzaghi, Karl; Peck, Ralph B.; Mesri, Gholamreza. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice. New York: Wiley, 1996.

- "Two Towns Swept By Montana Flood." The New York Times. April 16, 1908.

- Upper Missouri River Reservoir Fisheries Management Plan, 2010–2019. Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Commission. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. May 13, 2010. Archived from the original on September 21, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- Wegmann, Edward (1918). The Design and Construction of Dams. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 298.

Hauser Dam April 14.

External links

edit- Hauser Dam page on the PPL corporate Web site

- Pictures of Hauser Dam construction at the "Helena As She Was" history site

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. MT-108, "Hauser Hydroelectric Facility, Hauser Dam Road, Helena, Lewis and Clark County, MT", 8 data pages

- HAER No. MT-108-A, "Hauser Hydroelectric Facility, Powerhouse", 31 photos, 26 data pages, 5 photo caption pages