Heinrich Gottfried Piegler (* 23 February 1797 in Schleiz, Principality of Reuss j.L., today Thuringia; † 6 February 1849 in Schleiz) was a German entrepreneur and manufacturer who produced the first "modern" lighters which delivered a flame at the pressure of a lever, the so-called Döbereiner lighters, in large quantities in Schleiz and sold them worldwide.[1]

Life and achievement

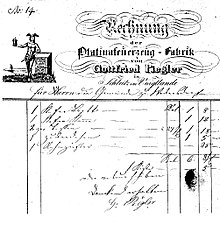

editGottfried Piegler was born as the fourth of six children of the master baker Christian Friedrich Piegler (1768-1806) and his wife Christiana Dorothea Rudolph (1754-1831), who moved to Schleiz from Ölsnitz/Vogtl. around 1790. His brothers took different paths, some of them became bakers like their father in Schleiz, another took up theology studies in Leipzig, but soon this patriot was drawn to the "Banner of the Voluntary Saxons" to follow Napoleon's troops. The youngest son, Gottfried, turned to the needlework.[2] His years of travel led him via Kassel to Frankfurt/M., where he worked at the main guard for Master Domschiez, fell seriously ill and, without a master craftsman's certificate in his pocket, had to be brought back home. For more than one year his serious illness continued. In 1819 he made a desperate plea to the then ruling Reussian prince Heinrich LXII to allow him to operate a manufactory outside the guild in Schleiz at Markt 1. The prince complied with his request on 4 February 1819. Despite a leg amputation in 1824, which became necessary due to unspeakable pain, Gottfried Piegler became one of the most successful entrepreneurs of the city at that time and has carried its good reputation throughout the world. He was one of the first in the world to technically implement the sensational discovery of platinum catalysis (1823) by the Jena professor of chemistry, Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, by mass-producing platinum ignition machines from the mid-1820s onwards and marketing them on a large scale worldwide! The head of the invoice was emblazoned with the words "Platinum lighter factory". The Piegler factory described itself as the "oldest factory" and warehouse of platinum lighters, platinum smoking machines, platinum sponges and all the associated utensils.[3][4]

The lighter containers were available in various, sometimes very artistic designs: in glass (clear, ruby red, cobalt blue), porcelain, earthenware, lacquered wood and sheet metal. The mechanics were also different, although in the higher-priced versions the fire did not have to be taken directly with a fidibus, but a small lamp lit up.[5] Publications by the renowned English chemist John Meurig Thomas show that Gottfried Piegler mass-produced hundreds of thousands of Döbereiner's lighters after 1828.[6][7] A few 20.000 were in use in England alone that year. There were business connections "from Aachen to Königsberg and from Hamburg to Constance", but also to France, Holland, Switzerland, England, Poland, Lithuania, Russia, Italy, Spain and the USA. Lithographed instructions for use in French, English, Italian and Spanish were a matter of course. The great demand for blasting machines meant that Gottfried Piegler was also able to place orders with other belt makers in the vicinity (e.g. Grünler and Kneusel in Zeulenroda). The workshops of Piegler and Holzschuher in Schleiz alone employed 40 to 50 beltmaker journeymen in the heyday, who, well paid, achieved regional fame as "Piegler's Journeymen".[8] Gottfried Piegler was regularly represented with his products at all major fairs in Germany (e.g. Leipzig), and in 1851 also at the first world exhibition ("Great Exhibition") in the Crystal Palace in London[9] and in 1853 at the Great Industrial Exhibition in Dublin.[10] A student of Döbereiner, Rudolf Christian Böttger from Frankfurt/M., introduced the practical and cheap safety matches ("Schwedenhölzer") in 1848, which soon outstripped the expensive but aristocratic table lighters. Nevertheless, these were manufactured and delivered by Gottfried Piegler's sons until the end of the 19th century. Gottfried Piegler's factory switched production to hairdressing supplies with the advent of fashion hairdressers at the end of the 19th century, which led to a new flowering of the factory in the following decades. After the First World War, the factory moved to newly built, larger premises in Moltke Street (today: BAD Health Centre Rudolf-Breitscheidstr. 6). In the wake of the Second World War, the last company owners, Theodor (1904-1991) and Kurt Piegler (1900-1969), had to leave Schleiz. They continued production in Nuremberg under the company name "Gebr. Piegler, formerly Gottfried Piegler" until 1975 in Langen Gasse 15.

On November 25, 1824, Gottfried Piegler married Friederike Henriette Köber (1802-1883), daughter of a red tanner, with whom he lived in a happy marriage and had five sons and two daughters.

Since 2012, the former residential and commercial buildings in Schleiz, as well as burial grounds on the town's cemetery situated on a hill above and a street named after Gottfried Piegler are commemorating him and his descendants. Döbereiner lighters from his production could be found in the castle museum of the town of Schleiz,[11] which was destroyed in the Second World War and can still be found in the museums in the surrounding area (e.g. Hof, Lobenstein, Plauen and Zeulenroda). On the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the company,[12] the Historical and Local History Association of Schleiz e.V. held a festive event on 4 May 2019 with Mayor M. Bias, chemist D. Linke (Berlin) and great-great-grandson T. Piegler (Physician in Hamburg) and dedicated its first special exhibition in the rooms of the museum Rutheneum, which was reopened in 2018, to this subject.[13]

Honours

editGottfried Piegler's great success prompted his sovereign, Prince Heinrich LXII Reuss j.L., to appoint him as "Court Commissar" by decree of 30 December 1847 "in recognition of the merits he had acquired by founding a new branch of industry in the town here". In February 2014, the city council of Schleiz honored this great Schleiz entrepreneur and named a street in the industrial area after him "Gottfried-Piegler-Straße".[14]

References

edit- ^ Alwin Mittasch, Erich Theis: From Davy and Döbereiner to Deacon - half a century of interface catalysis. Publisher Chemie, Berlin 1932, p. 68 ff.

- ^ Theo Piegler: Vogtländische Schicksale. Videel, Niebüll 2005, ISBN 3-89906-996-X, p. 105 ff.

- ^ Alwin Mittasch: Döbereiner, Goethe and the catalysis. Hippocrates, Stuttgart 1951, p. 51.

- ^ Theo Piegler: Fire from Schleiz. Videel, Niebüll 2001, ISBN 3-935111-50-9, pp. 115-155.

- ^ F. von Gizycki: A Döbereiner lighter of rare kind. In: Sudhoff's archive. Volume 41, 1957, p. 89.

- ^ John M. Thomas: Turning Points in Catalysis. In: Applied Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. volume 33, 1994, p. 914.

- ^ John M. Thomas: The RSC Faraday prize lecture of 1989. In: Chem. Commun. Volume 53, 2017, p. 9189.

- ^ Schleiz fifty years ago. In: Schleizer Wochenblatt. No. 115, September 28, 1872, p. 51.

- ^ Official list of the objects sent from the German Customs Union and Northern Germany to the Industrial Exhibition of All Nations in London. Decker, Berlin 1851, p. 266 (digitalization)

- ^ Falconer, John (1853). Official catalogue of the Great Industrial Exhibition (1853). Dublin: Committee of the Great Exhibition. p. 110.

- ^ Behr, Bruno (1927). Unser Oberland (in German). Schleiz: Oberland. p. 9.

- ^ Piegler, Theo (2018). 200 Jahre Fa. Gottfried Piegler in Schleiz (in German). Schleiz: Landratsamt des Saale-Orla-Kreises. pp. 60–64.

- ^ Uwe Lange: It "pieglers" at many corners in Schleiz. Ostthüringer Zeitung. May 6, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019

- ^ Schleiz City Council renames street "Am Wolfsgalgen" in the industrial park. Ostthüringer Zeitung. February 8, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2019.