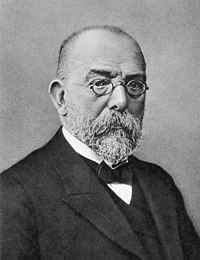

Koch's postulates (/kɒx/ KOKH)[2] are four criteria designed to establish a causal relationship between a microbe and a disease. The postulates were formulated by Robert Koch and Friedrich Loeffler in 1884, based on earlier concepts described by Jakob Henle, and the statements were refined and published by Koch in 1890.[3] Koch applied the postulates to describe the etiology of cholera and tuberculosis, both of which are now ascribed to bacteria. The postulates have been controversially generalized to other diseases. More modern concepts in microbial pathogenesis cannot be examined using Koch's postulates, including viruses (which are obligate intracellular parasites) and asymptomatic carriers. They have largely been supplanted by other criteria such as the Bradford Hill criteria for infectious disease causality in modern public health and the Molecular Koch's postulates for microbial pathogenesis.[4]

Postulates

editKoch's four postulates are:[5]

- The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease but should not be found in healthy organisms.

- The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

- The cultured microorganism should cause disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

- The microorganism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.[a]

However, Koch later abandoned the universalist requirement of the first postulate when he discovered asymptomatic carriers of cholera[6] and, later, of typhoid fever.[7] Subclinical infections and asymptomatic carriers are now known to be a common feature of many infectious diseases, especially viral diseases such as polio, herpes simplex, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, and COVID-19. For example, poliovirus only causes paralysis in a small percentage of those infected.[7]

The second postulate does not apply to pathogens incapable of growing in pure culture. For example, viruses are dependent on entering and hijacking host cells to use their resources for growth and reproduction, incapable of growing alone.[8]

The third postulate specifies "should", rather than "must", because Koch's experiments with tuberculosis and cholera showed that not all organisms exposed to an infectious agent will acquire the infection.[9] Some individuals may avoid infection by maintaining their health for proper immune functioning, acquiring immunity from previous exposure or vaccination, or through genetic immunity, such as sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease conferring resistance to malaria.[10]

Other exceptions to Koch's postulates include evidence that some pathogens can cause several diseases, such as the varicella-zoster virus causing chickenpox and shingles. Conversely, diseases like meningitis can be caused by a variety of bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic pathogens.[11]

History

editRobert Koch developed the postulates based on pathogens that could be isolated using 19th century methods.[12] Nonetheless, Koch was already aware that the causative agent of cholera, Vibrio cholerae, could be found in both sick and healthy people, invalidating his first postulate.[6][9] Since the 1950s, Koch's postulates have been treated as obsolete for epidemiology research, but they are still taught to emphasize historical approaches to determining the microbial causative agents of disease.[3][13]

Koch formulated his postulates too early in the history of virology to recognize that many viruses do not cause illness in all infected individuals, a requirement of the first postulate. HIV/AIDS denialism includes claims that the viral spread of HIV/AIDS violates Koch's second postulate, despite that criticism being applicable to all viruses. Nonetheless, HIV/AIDS fulfills all of the other postulates with all AIDS patients being HIV-positive and laboratory workers exposed to HIV eventually developing the same symptoms of AIDS.[14] Similarly, evidence that some oncovirus infections can contribute to cancers has been unfairly criticized for failing to fulfill criteria developed before viruses were fully understood as host-dependent. [15]

The bacterial pathogen Staphylococcus aureus showcases lethal synergy with the opportunistic fungi Candida albicans by using the latter's extracellular matrix to protect itself from host immune cells and antibiotic compounds.[16] Biofilm-producing species aim to clump individual cells on solid or liquid surfaces, growing poorly in a pure culture and leaving those that survive potentially too weak to cause disease if transferred to a healthy organism, violating the second and third postulates.[17]

Physicians Barry Marshall and Robin Warren argued that Helicobacter pylori contributes to peptic ulcer disease, but throughout the early 1980s, the scientific community initially rejected their findings because not all H. pylori infections cause peptic ulcers, violating the first postulate.[18]

Priority effects are another major concern, as the success of pathogenic bacteria is dependent on the other species already colonizing that habitat, as the earliest resident microbes establish the environmental conditions, providing colonization resistance against certain species.[19]

Molecular Koch's postulates

editIn 1988, microbiologist Stanley Falkow developed a set of three Molecular Koch's postulates for identifying the microbial genes encoding virulence factors. First, the phenotype of a disease symptom must be associated with a specific genotype only found in pathogenic strains. Second, that symptom should not be present when the associated gene is inactivated. Third, the symptom should return when the gene is reactivated.[20]

Modern DNA sequencing allows researchers to identify whether the genes of specific pathogens are only present in infected hosts, offering a modified approach for determining correlation between viruses and certain diseases. Since viruses cannot grow in axenic cultures, requiring a host cell to hijack for growth and replication, scientists are limited to analyzing which viral genes contribute to host diseases. Additionally, this method has supported correlations between prions (pathogenic misfolded proteins) and conditions like Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease because Koch's postulates are focused on foreign microorganisms, rather than the results of host mutations.[21]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Koch R (1876). "Untersuchungen über Bakterien: V. Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus anthracis" [Investigations into bacteria: V. The etiology of anthrax, based on the ontogenesis of Bacillus anthracis] (PDF). Cohns Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen (in German). 2 (2): 277–310.

- ^ "Koch". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b Evans AS (October 1978). "Causation and disease: a chronological journey. The Thomas Parran Lecture". American Journal of Epidemiology. 108 (4): 249–258. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112617. PMID 727194.

- ^ Fredricks D, Ramakrishnan L (April 2006). "The Acetobacteraceae: extending the spectrum of human pathogens". PLOS Pathogens. 2 (4): e36. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020036. PMC 1447671. PMID 16652172.

- ^ a b Walker L, LeVine H, Jucker M (2006). "Koch's Postulates and Infectious Proteins". Acta Neuronathologica. 112 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0072-x. PMC 8544537. PMID 16703338.

- ^ a b Koch R (1893). "Ueber den augenblicklichen Stand der bakteriologischen Choleradiagnose" [About the current state of the bacteriological diagnosis of cholera]. Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten (in German). 14: 319–38. doi:10.1007/BF02284324. S2CID 9388121.

- ^ a b "10.1E: Exceptions to Koch's Postulates". Biology LibreTexts. 2018-06-20. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Inglis TJ (November 2007). "Principia aetiologica: taking causality beyond Koch's postulates". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 56 (Pt 11): 1419–1422. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.47179-0. PMID 17965339.

- ^ a b Koch R (1884). "Die Aetiologie der Tuberkulose" [The etiology of tuberculosis]. Mittheilungen aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte (Reports from the Imperial Office of Public Health) (in German). 2: 1–88.

- ^ Archer NM, Petersen N, Clark MA, Buckee CO, Childs LM, Duraisingh MT (July 2018). "Resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in sickle cell trait erythrocytes is driven by oxygen-dependent growth inhibition". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (28): 7350–7355. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.7350A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1804388115. PMC 6048551. PMID 29946035.

- ^ Slonczewski J, Foster J, Zinser E (June 26, 2020). Microbiology: An Evolving Science (5th ed.). New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 14–20. ISBN 978-0-393-93447-2.

- ^ Walker L, Levine H, Jucker M (July 2006). "Koch's postulates and infectious proteins". Acta Neuropathologica. 112 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0072-x. PMC 8544537. PMID 16703338. S2CID 22210933.

- ^ Huebner RJ (April 1957). "Criteria for etiologic association of prevalent viruses with prevalent diseases; the virologist's dilemma". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 67 (8): 430–438. Bibcode:1957NYASA..67..430H. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb46066.x. PMID 13411978. S2CID 84622170.

- ^ Steinberg J (June 23, 2009). "Five Myths about HIV and AIDS". New Scientist. Retrieved 2023-01-14.

- ^ Moore PS, Chang Y (June 2014). "The conundrum of causality in tumor virology: the cases of KSHV and MCV". Seminars in Cancer Biology. 26: 4–12. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.11.001. PMC 4040341. PMID 24304907.

- ^ Todd OA, Peters BM (September 2019). "Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus Pathogenicity and Polymicrobial Interactions: Lessons beyond Koch's Postulates". Journal of Fungi. 5 (3): 81. doi:10.3390/jof5030081. PMC 6787713. PMID 31487793.

- ^ Hosainzadegan H, Khalilov R, Gholizadeh P (February 2020). "The necessity to revise Koch's postulates and its application to infectious and non-infectious diseases: a mini-review". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 39 (2): 215–218. doi:10.1007/s10096-019-03681-1. PMID 31440916. S2CID 201283277.

- ^ Marshall BJ, Armstrong JA, McGechie DB, Glancy RJ (April 1985). "Attempt to fulfil Koch's postulates for pyloric Campylobacter". The Medical Journal of Australia. 142 (8): 436–439. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb113443.x. PMID 3982345. S2CID 42243517.

- ^ Byrd AL, Segre JA (January 2016). "Infectious disease. Adapting Koch's postulates". Science. 351 (6270): 224–226. Bibcode:2016Sci...351..224B. doi:10.1126/science.aad6753. PMID 26816362. S2CID 29595548.

- ^ Falkow S (1988). "Molecular Koch's postulates applied to microbial pathogenicity". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 10 (Suppl 2): S274–S276. doi:10.1093/cid/10.Supplement_2.S274. PMID 3055197.

- ^ Fredricks DN, Relman DA (January 1996). "Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch's postulates". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 9 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.1.18. PMC 172879. PMID 8665474.

Further reading

edit- "Contagion: Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics". Harvard Library Open Collections Program.

- Koch R (April 1882). "Die Aetiologie der Tuberculose". Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift [Berlin Clinical Weekly] (in German) (15): 221–230.

- Koch R (1884). "Die Aetiologie der Tuberkulose". Mittbeilungen aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundbeisamte [Information from the Imperial Health Committee] (in German). 2: 1–88. English translation in Koch R (1962). "The Etiology of Tuberculosis". In Brock TD (ed.). Milestones in Microbiology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall International. pp. 116–. OCLC 557930518.

- Loeffler F (1884). "Untersuchungen über die Bedeutung der Mikroorganismen für die Entstehung der Diphtherie beim Menschen, bei der Taube und beim Kalbe" [Investigations into the importance of microorganisms for the development of diphtheria in humans, pigeons and calves]. Mitteilungen aus dem kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte [Communications from the Imperial Health Office]. 2: 421–499. hdl:2027/rul.39030039500568 – via HathiTrust.