Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 – November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the Republican Party, he served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. His successful crusade against Woodrow Wilson's Treaty of Versailles ensured that the United States never joined the League of Nations and his penned conditions against that treaty, known collectively as the Lodge reservations, influenced the structure of the modern United Nations.[3][4]

Henry Cabot Lodge | |

|---|---|

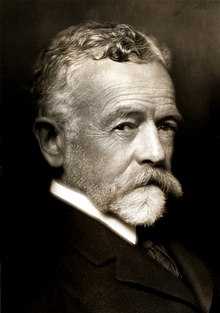

Lodge in 1905 | |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts | |

| In office March 4, 1893 – November 9, 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Henry L. Dawes |

| Succeeded by | William M. Butler |

| Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee | |

| In office May 19, 1919 – November 9, 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Gilbert Hitchcock |

| Succeeded by | William Borah |

| Senate Majority Leader | |

| In office May 19, 1919 – November 9, 1924 | |

| Deputy | Charles Curtis |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Charles Curtis |

| Chairman of the Senate Republican Conference | |

| In office August 17, 1918 – November 9, 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Jacob Harold Gallinger |

| Succeeded by | Charles Curtis |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office May 25, 1912 – May 30, 1912 | |

| Preceded by | Augustus Octavius Bacon |

| Succeeded by | Augustus Octavius Bacon |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 6th district | |

| In office March 4, 1887 – March 3, 1893 | |

| Preceded by | Henry B. Lovering |

| Succeeded by | William Cogswell |

| Chair of the Massachusetts Republican Party | |

| In office January 31, 1883 – 1884 | |

| Preceded by | Charles A. Stott |

| Succeeded by | Edward Avery |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the 10th Essex district[a] | |

| In office January 7, 1880 – January 3, 1882 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel R. Pinkham[1] William Lyon[1] |

| Succeeded by | John Marlor[2] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 12, 1850 Beverly, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | November 9, 1924 (aged 74) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Anna Cabot Mills Davis

(m. 1871) |

| Children | 3, including George |

| Relatives | |

| Education | Harvard University (AB, LLB, AM, PhD) |

| Signature | |

Lodge received four degrees from Harvard University and was a widely published historian. His close friendship with Theodore Roosevelt began as early as 1884 and lasted their entire lifetimes, even surviving Roosevelt's bolt from the Republican Party in 1912.

As a representative, Lodge sponsored the unsuccessful Lodge Bill of 1890, which sought to protect the voting rights of African Americans and introduce a national secret ballot. As a senator, Lodge took a more active role in foreign policy, supporting the Spanish–American War, expansion of American territory overseas, and American entry into World War I. He also supported immigration restrictions, becoming a member of the Immigration Restriction League and influencing the Immigration Act of 1917.

After World War I, Lodge became Chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the leader of the Senate Republicans. From that position, he led the opposition to Wilson's Treaty of Versailles, proposing 14 reservations to the treaty.[3] His strongest objection was to the requirement that all nations repel aggression, fearing that this would erode congressional powers and erode American sovereignty; those objections had a major role in producing the veto power of the United Nations Security Council. Lodge remained in the Senate until his death in 1924.

Early life and education

editLodge was born in Beverly, Massachusetts. His father was John Ellerton Lodge of the Lodge family. His mother was Anna Cabot, a member of the Cabot family,[5] through whom he was a great-grandson of George Cabot. Lodge was a Boston Brahmin. He grew up on Boston's Beacon Hill and spent part of his childhood in Nahant, Massachusetts, where he witnessed the 1860 kidnapping of a classmate and gave testimony leading to the arrest and conviction of the kidnappers.[6] When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Lodge's father wanted to ride into battle at the head of a cavalry regiment he had personally put together, but his father missed the chance, possibly due to a bad knee from a riding injury, and in September 1862, Lodge's father suddenly died.[7] He was cousin to the American polymath Charles Peirce.

In 1872, he graduated from Harvard College, where he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon, the Porcellian Club, and the Hasty Pudding Club. In 1874, he graduated from Harvard Law School, and was admitted to the bar in 1875, practicing at the Boston firm now known as Ropes & Gray.[8]

Historian

editAfter traveling through Europe, Lodge returned to Harvard, and, in 1876, became one of the earliest recipients of a PhD in history from an American university.[9][10] Lodge's dissertation, "The Anglo-Saxon Land Law", was published in a compilation "Essays in Anglo-Saxon Law", alongside his PhD classmates: James Laurence Laughlin on "The Anglo-Saxon Legal Procedure" and Ernest Young on "The Anglo-Saxon Family Law". All three were supervised by Henry Adams, who contributed "The Anglo-Saxon Courts of Law".[10][11] Lodge maintained a lifelong friendship with Adams.[12]

As a popular historian of the United States, Lodge focused on the early Federalist Era. He published biographies of George Washington and the prominent Federalists Alexander Hamilton, Daniel Webster, and his great-grandfather George Cabot, as well as A Short History of the English Colonies in America. In 1898, he published The Story of the Revolution in serial form in Scribner's Magazine.

Lodge was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1878.[13] In 1881, he was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.[14] He was also a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and served as its president from 1915 to 1924.[15] As such, Lodge penned a preface to The Education of Henry Adams (which had been written by Adams in 1905 and printed in a private edition for family and friends) when this classic autobiography was posthumously published by the Massachusetts Historical Society in September 1918.

Political career

editIn 1880–1882, Lodge served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Lodge represented his home state in the United States House of Representatives from 1887 to 1893 and in the Senate from 1893 to 1924.[16]

Along with his close friend Theodore Roosevelt, Lodge was sympathetic to the concerns of the Mugwump faction of the Republican Party. Nonetheless, both reluctantly supported James Blaine and protectionism in the 1884 election. Blaine lost narrowly.[17]

Lodge was first elected to the US Senate in 1892 and easily reelected time and again but his greatest challenge came in his reelection bid in January 1911. The Democrats had made significant gains in Massachusetts and the Republicans were split between the progressive and conservative wings, with Lodge trying to mollify both sides. In a major speech before the legislature voted, Lodge took pride in his long selfless service to the state. He emphasized that he had never engaged in corruption or self-dealing. He rarely campaigned on his own behalf but now he made his case, explaining his important roles in civil service reform, maintaining the gold standard, expanding the Navy, developing policies for the Philippine Islands, and trying to restrict immigration by illiterate Europeans, as well as his support for some progressive reforms. Most of all he appealed to party loyalty. Lodge was reelected by five votes.[18]

Lodge was very close to Theodore Roosevelt for both of their entire careers. However, Lodge was too conservative to accept Roosevelt's attacks on the judiciary in 1910, and his call for the initiative, referendum, and recall. Lodge stood silent when Roosevelt broke with the party and ran as a third-party candidate in 1912. Lodge voted for Taft instead of Roosevelt; after Woodrow Wilson won the election the Lodge-Roosevelt friendship resumed.[19]

Civil rights

editIn 1890, Lodge co-authored the Federal Elections Bill, along with Senator George Frisbie Hoar, that guaranteed federal protection for African American voting rights. Although the proposed legislation was supported by President Benjamin Harrison, the bill was blocked by filibustering Democrats in the Senate.[20]

In 1891, he became a member of the Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. He was assigned national membership number 4,901.

That same year, following the lynching of eleven Italian Americans in New Orleans, Lodge published an article blaming the victims and proposing new restrictions on Italian immigration.[21][22]

Lodge’s support for voting rights did not extend to women. He was a leading opponent of women’s suffrage.[23] Lodge did not change his position even after the junior senator from Massachusetts, John Weeks, lost his seat in 1918 due to his opposition to equal suffrage.[24]

Spanish–American War

editLodge was a strong backer of U.S. intervention in Cuba in 1898, arguing that it was the moral responsibility of the United States to do so:

Of the sympathies of the American people, generous, liberty-loving, I have no question. They are with the Cubans in their struggle for freedom. I believe our people would welcome any action on the part of the United States to put an end to the terrible state of things existing there. We can stop it. We can stop it peacefully. We can stop it, in my judgment, by pursuing proper diplomacy and offering our good offices. Let it once be understood that we mean to stop the horrible state of things in Cuba and it will be stopped. The great power of the United States, if it is once invoked and uplifted, is capable of greater things than that.

Following American victory in the Spanish–American War, Lodge came to represent the imperialist faction of the Senate, those who called for the annexation of the Philippines. Lodge maintained that the United States needed to have a strong navy and be more involved in foreign affairs. However, Lodge was never on good terms with John Hay, who served as Secretary of State under McKinley and Roosevelt, 1898–1905. They had a bitter fight over the principle of commercial reciprocity with Newfoundland.[25]

In a letter to Theodore Roosevelt, Lodge wrote, "Porto Rico is not forgotten and we mean to have it".[26]

Immigration

editLodge was a vocal proponent of immigration restrictions, for a number of reasons. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, significant numbers of immigrants, primarily from Eastern and Southern Europe, were migrating to industrial centers in the United States. Lodge argued that unskilled foreign labor was undermining the standard of living for American workers, and that a mass influx of uneducated immigrants would result in social conflict and national decline. In a May 1891 article on Italian immigration, Lodge expressed his concern that immigration by "the races who have peopled the United States" was declining, while "the immigration of people removed from us in race and blood" was on the rise.[27] He considered northern Italians superior candidates for immigration to southern Italians, not only because they tended to be better educated, had a higher standard of living, and had a "higher capacity for skilled work",[28] but because they were more "Teutonic" than their southern counterparts, whose immigration he sought to restrict.[28][29]

Lodge was a supporter of "100% Americanism", a common theme in the nativist movement of the era. In an address to the New England Society of Brooklyn in 1888, Lodge stated:

Let every man honor and love the land of his birth and the race from which he springs and keep their memory green. It is a pious and honorable duty. But let us have done with British-Americans and Irish-Americans and German-Americans, and so on, and all be Americans ... If a man is going to be an American at all let him be so without any qualifying adjectives; and if he is going to be something else, let him drop the word American from his personal description.[30]

He did not believe, however, that all races were equally capable or worthy of being assimilated. In The Great Peril of Unrestricted Immigration, he wrote that "you can take a Hindoo and give him the highest education the world can afford ... but you cannot make him an Englishman" and cautioned against the mixing of "higher" and "lower" races:

On the moral qualities of the English-speaking race, therefore, rest our history, our victories, and all our future. There is only one way in which you can lower those qualities or weaken those characteristics, and that is by breeding them out. If a lower race mixes with a higher in sufficient numbers, history teaches us that the lower race will prevail.[31]

As the public voice of the Immigration Restriction League, Lodge argued in support of literacy tests for incoming immigrants. The tests would be designed to exclude members of those races he deemed "most alien to the body of the American people".[32] He proposed that the United States should temporarily shut out all further entries, particularly persons of low education or skill, to more efficiently assimilate the millions who had already come. From 1907 to 1911, he served on the Dillingham Commission, a joint congressional committee established to study the era's immigration patterns and make recommendations to Congress based on its findings. The Commission's recommendations led to the Immigration Act of 1917.

World War I

editLodge was a staunch advocate of entering World War I on the side of the Allied Powers, attacking President Woodrow Wilson for poor military preparedness and accusing pacifists of undermining American patriotism.[citation needed] On April 2, 1917, the day that President Wilson urged Congress to declare war, Lodge and Alexander Bannwart, a pacifist constituent who wanted Lodge to vote against the war, got into a fistfight in the U.S. Capitol. Bannwart was arrested[33] but Lodge opted not to press charges. Bannwart later sued Lodge to have the record corrected; initial news reports suggested that Bannwart hit Lodge first, but Lodge acknowledged in settling the lawsuit that he had hit Bannwart first. This is the only known instance of a U.S. Senator attacking a constituent.[34]

After the United States entered the war, Lodge continued to attack Wilson as hopelessly idealistic, assailing Wilson's Fourteen Points as unrealistic and weak. He contended that Germany needed to be militarily and economically crushed and saddled with harsh penalties so that it could never again be a threat to the stability of Europe. However, apart from policy differences, even before the end of Wilson's first term and well before America's entry into the Great War, Lodge confided to Teddy Roosevelt, "I never expected to hate anyone in politics with the hatred I feel toward Wilson."[35] In January 1921, Lodge led the deliberate obstruction of the confirmation of 10,000 presidential Wilson appointments to the War and Navy Departments in the US Senate on the grounds that confirmation of these so-called cabinet "favorite" appointments would embarrass the Harding Administration.[36]

He served as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (1919–1924). He also served as chairman of the Senate Republican Conference from 1918 to 1924. His leadership of the Senate Republicans has led some to retrospectively call him the de facto Senate Majority Leader.[37] During his term in office, he and another powerful senator, Albert J. Beveridge, pushed for the construction of a new navy.

League of Nations

editIn 1919, as the unofficial Senate majority leader, Lodge dealt with the debate over the Treaty of Versailles and the Senate's ultimate rejection of the treaty. Lodge wanted to join the League of Nations, but with amendments that would protect American sovereignty.

Lodge appealed to the patriotism of American citizens by objecting to what he saw as the weakening of national sovereignty: "I have loved but one flag and I can not share that devotion and give affection to the mongrel banner invented for a league." Lodge was reluctant to involve the United States in world affairs in anything less than a pre-eminent role:

The United States is the world's best hope, but if you fetter her in the interests and quarrels of other nations, if you tangle her in the intrigues of Europe, you will destroy her power for good, and endanger her very existence. Leave her to march freely through the centuries to come, as in the years that have gone. Strong, generous, and confident, she has nobly served mankind. Beware how you trifle with your marvelous inheritance; this great land of ordered liberty. For if we stumble and fall, freedom and civilization everywhere will go down in ruin.[38]

Lodge was also motivated by political concerns; he strongly disliked Wilson personally[39] and was eager to find an issue for the Republican Party to run on in the presidential election of 1920.

Lodge's key objection to the League of Nations was Article X, which required all signatory nations to repel aggression of any kind if ordered to do so by the League. Lodge rejected an open-ended commitment that might subordinate the national security interests of the United States to the demands of the League. He especially insisted that Congress must approve interventions individually; the Senate could not, through treaty, unilaterally agree to enter hypothetical conflicts. Despite Lodge hypocrital whining Article X did not infringe on the right of the United States to make war; Article X "...required [but did not force] members to assist any other member nation in the event of an invasion or attack... In fact the intent of Article X was to mantain a Balance of power (international relations) by preventing one nation from attacking another (i.e. Germany attacking Belgium and France in 1914).

The Senate was divided into a "crazy-quilt" of positions on the Versailles question.[40] One block of Democrats strongly supported the Treaty. A second group of Democrats, in line with President Wilson, supported the Treaty and opposed any amendments or reservations.[3] The largest bloc, led by Lodge, comprised a majority of the Republicans. They supported a Treaty with reservations, especially on Article X.[41] Finally, a bi-partisan group of 13 isolationist "irreconcilables" opposed a treaty in any form.

It proved possible to build a majority coalition, but impossible to build a two thirds coalition that was needed to pass a treaty.[42] The closest the Treaty came to passage was in mid-November 1919, when Lodge and his Republicans formed a coalition with the pro-Treaty Democrats, and were close to a two-thirds majority for a Treaty with reservations, but Wilson rejected this compromise.[3]

Cooper and Bailey suggest that Wilson's stroke on September 25, 1919, had so altered his personality that he was unable to effectively negotiate with Lodge. Cooper says the psychological effects of a stroke were profound: "Wilson's emotions were unbalanced, and his judgment was warped. ... Worse, his denial of illness and limitations was starting to border on delusion."[43]

The Treaty of Versailles went into effect, but the United States did not sign it and made separate peace with Germany and Austria-Hungary. The United States never joined the League of Nations.[3] Historians agree that the League was ineffective in dealing with major issues, but they debate whether American membership would have made much difference.[44]

Lodge won out in the long run; his reservations were incorporated into the United Nations charter in 1945, with Article X of the League of Nations charter absent and the U.S., as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, given an absolute veto.[4] Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Lodge's grandson, served as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations from 1953 to 1960.

Obstruction of Wilson appoiments

editIn January 1921, Lodge led the deliberate obstruction of the confirmation of 10,000 presidential Wilson appointments to the War and Navy Departments in the US Senate on the grounds that confirmation of these so-called cabinet "favorite" appointments would embarrass the Harding Administration.[45]

Washington Naval Conference

editIn 1922, President Warren G. Harding appointed Lodge as a delegate to the Washington Naval Conference (International Conference on the Limitation of Armaments), led by Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, and included Elihu Root and Oscar Underwood. This was the first disarmament conference in history and had a goal of world peace through arms reduction. Attended by nine nations, the United States, Japan, China, France, Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Portugal, the conference resulted in three major treaties: Four-Power Treaty, Five-Power Treaty (more commonly known as the Washington Naval Treaty), and the Nine-Power Treaty, as well as a number of smaller agreements.[46]

Lodge–Fish Resolution

editIn June 1922, he introduced the Lodge–Fish Resolution, to illustrate American support for the British policy in Palestine per the 1917 Balfour Declaration.

Legacy

editHistorian George E. Mowry argues that:

Henry Cabot Lodge was one of the best informed statesmen of his time, he was an excellent parliamentarian, and he brought to bear on foreign questions a mind that was at once razor sharp and devoid of much of the moral cant that was so typical of the age. ... [Yet] Lodge never made the contributions he should have made, largely because of Lodge the person. He was opportunistic, selfish, jealous, condescending, supercilious, and could never resist calling his opponent's spade a dirty shovel. Small wonder that except for Roosevelt and Root, most of his colleagues of both parties disliked him, and many distrusted him.[47]

Lodge served on the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for many years. His first appointment was in 1890, as a Member of the House of Representatives, and he served until his election as a senator in 1893. He was reappointed to the Board in 1905 and served until he died in 1924. The other Regents considered Lodge to be a "distinguished colleague, whose keen, constructive interest in the affairs of the Institution led him to place his broad knowledge and large experience at its service at all times."[48]

Mount Lodge, also named Boundary Peak 166, located on the Canada–United States border in the Saint Elias Mountains was named in 1908 after him in recognition of his service as U.S. Boundary Commissioner in 1903.[49]

Lodge was depicted by Sir Cedric Hardwicke in Darryl Zanuck's 1944 film Wilson, a biography of President Wilson.

Personal life

editIn 1871, he married Anna "Nannie" Cabot Mills Davis,[50] daughter of Admiral Charles Henry Davis. They had three children:[51]

- Constance Davis Lodge (1872–1948), wife of U.S. Representative Augustus Peabody Gardner (from 1892 to 1918) and Brigadier General Clarence Charles Williams (from 1923 to 1948)

- George Cabot Lodge I (1873–1909), a noted poet and politician. George's sons, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (1902–1985) and John Davis Lodge (1903–1985), also became politicians.[52]

- John Ellerton Lodge II (1876–1942), an art curator.[53]

On November 5, 1924, Lodge suffered a severe stroke while recovering in the hospital from surgery for gallstones.[54] He died four days later at the age of 74.[55] He was interred in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[56]

Publications

editBooks written by Lodge

edit- 1877. Life and Letters of George Cabot. Little, Brown.

- 1880. Ballads and Lyrics, Selected and Arranged by Henry Cabot Lodge. Houghton Mifflin (1882 reissue contains a Preface by Lodge)

- 1881. A Short History of the English Colonies in America. Harper & Bros.

- 1882. Alexander Hamilton. Houghton Mifflin (American Statesmen Series).

- 1883. Daniel Webster. Houghton Mifflin (American Statesmen Series).

- 1887. Alexander Hamilton. Houghton Mifflin (American Statesmen Series).

- 1889. George Washington. (2 volumes). Houghton Mifflin (American Statesmen series).

- 1891. Boston. Longmans, Green, and Co. (Historic Towns series).

- 1892. Speeches. Houghton Mifflin.

- 1895. Hero Tales from American History. With Theodore Roosevelt. Century.

- 1898. The Story of the Revolution. (2 volumes). Charles Scribner's Sons.

- 1899. The War With Spain. Harper & Brothers.

- 1902. A Fighting Frigate, and Other Essays and Addresses. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- 1906. A Frontier Town and Other Essays. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- 1909. Speeches and Addresses: 1884–1909. Houghton Mifflin.

- 1913. Early Memories. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- 1915. The Democracy of the Constitution, and Other Addresses and Essays. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- 1917. War Addresses, 1915-1917. Houghton Mifflin.

- 1919. Address of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts in Honor of Theodore Roosevelt, Ex-President of the United States, before the Congress of the United States Sunday, February 9, 1919. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- 1919. Theodore Roosevelt, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- 1921. The Senate of the United States and Other Essays and Addresses, Historical and Literary. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- 1925. The Senate and the League of Nations. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- 1925. Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, 1884–1918 (2 vol.). With Theodore Roosevelt.

Book chapters written by Lodge

edit- 1898. "The Great Peril of Unrestricted Immigration". The New Century Speaker for School and College. Ginn. 1898. pp. 177–179.

Book series edited by Lodge

edit- 1903. The Works of Alexander Hamilton. 12 vol.

- 1910. The History of Nations. Chicago: H. W. Snow, 1901; New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1913.

- 1916. Rome. New York : P.F. Collier & Son, 1916.

- 1909. The Best of the World's Classics, Restricted to Prose. (10 volumes). With Francis Whiting Halsey. Funk & Wagnalls.

Articles

edit- 1878. "Timothy Pickering" (PDF). The Atlantic. June 1878. pp. 740–756.

- 1882. "Daniel Webster" (PDF). The Atlantic. February 1882. pp. 228–243.

- 1882. "Naval Courts-Martial and the Pardoning Power" (PDF). The Atlantic. July 1882. pp. 43–51.

- 1883. "Colonialism in the United States" (PDF). The Atlantic. May 1883. pp. 612–626.

- 1890. "International Copyright" (PDF). The Atlantic. August 1890. pp. 264–271.

- 1891. "Lynch Law and Unrestricted Immigration". The North American Review. 152 (414): 602–612. May 1891.

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ The 10th Essex was a three-member district composed of Nahant and several wards of the city of Lynn. Lodge served alongside Charles A. Wentworth II and Bryan Harding in his first term (1880–81) and alongside Frank D. Allen and Hartwell S. French in his second term (1881–82).

References

edit- ^ a b "A manual for the use of the General Court". 1858.

- ^ "A manual for the use of the General Court". 1858.

- ^ a b c d e "The Great War: A Nation Comes of Age - Part 3, Transcript". American Experience. PBS. July 3, 2018. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Leo Gross, "The Charter of the United Nations and the Lodge Reservations." American Journal of International Law 41.3 (1947): 531-554. in JSTOR Archived February 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Henry Cabot Lodge Photographs ca. 1860–1945: Guide to the Photograph Collection". Massachusetts Historical Society Library. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ "How Henry Cabot Lodge earned his gold watch by John Mason". Yankee Magazine. August 1965. Archived from the original on August 23, 2010.

- ^ Thomas, Evan (April 27, 2010). The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898. Little, Brown. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-316-08798-8.

- ^ Carl M. Brauer, Ropes & Gray 1865–1992, (Boston: Thomas Todd Company, 1991.)

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Featured Bio Lodge". www.senate.gov. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "WHO'S ON FIRST?". Historians.org. December 1, 1989. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Essays in Anglo-Saxon Law. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1876. hdl:2027/hvd.32044005040381. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ John A. Garraty, Henry Cabot Lodge (1953)

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter L" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "MemberListL". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Claude Singer, The Grim Security of the Past: The Historiography of Henry Cabot Lodge, M.A. thesis, Portland State University (1973), p. 5.

- ^ "S. Doc. 58-1 - Fifty-eighth Congress. (Extraordinary session -- beginning November 9, 1903.) Official Congressional Directory for the use of the United States Congress. Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing by A.J. Halford. Special edition. Corrections made to November 5, 1903". GovInfo.gov. U.S. Government Printing Office. November 9, 1903. p. 47. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ David M. Tucker, Mugwumps: Public Moralists of the Gilded Age (1991).

- ^ John A. Garraty, Henry Cabot Lodge: A Biography (1953) 280-83

- ^ Garraty, Henry Cabot Lodge: A Biography (1953) 287-91, 323

- ^ Wilson, Kirt H. (2005). "1". The Politics of Place and Presidential Rhetoric in the United States, 1875–1901. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 32, 33. ISBN 978-1-58544-440-3. Retrieved November 19, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Leach, Eugene E. (1992). "Mental Epidemics: Crowd Psychology and American Culture, 1890–1940". American Studies. 33 (1). Mid-America American Studies Association: 5–29. JSTOR 40644255.

- ^ Lodge, Henry Cabot (May 1891). "Lynch Law and Unrestricted Immigration". The North American Review. 152 (414): 602–612. JSTOR 25102181.

- ^ Flexner, Eleanor (1975). Century of Struggle (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University. pp. 306–07.

- ^ DuBois, Ellen Carol (2020). Suffrage: Women's Long Battle for the Vote. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 249–50. ISBN 978-1-5011-6516-0.

- ^ Dennett, John Hay (1933), pp 421–429.

- ^ "Spanish-American War in Puerto Rico" (PDF). National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Lodge (1891), p. 611

- ^ a b Puleo, Stephen (2007). The Boston Italians. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9780807050361. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ Puleo, Stephen (2010). Dark Tide: The Great Molasses Flood of 1919. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780807096673.

- ^ Lodge, Henry Cabot (1892). Speeches. Houghton Mifflin. p. 46. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ Lodge, Henry Cabot (1898). "The Great Peril of Unrestricted Immigration". In Frink, Henry Allyn (ed.). The New Century Speaker for School and College. Ginn. pp. 177–179. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ O'Connor, Thomas H. (1995). The Boston Irish: A Political History. Back Bay Books. p. 156. ISBN 0-316-62661-9.

- ^ Groves, Charles S. (April 2, 1917). "Senator Lodge Right There With The Punch". The Boston Globe. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ DeCosta-Klipa, Nik (April 6, 2017). "100 years ago, the US entered WWI—and a senator from Massachusetts punched a protester in the face over it". Boston.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Berg, A. Scott (2013). Wilson. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 612. ISBN 978-0-399-15921--3. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ "The Washington Herald January 19,1921 p.1". Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "Henry Cabot Lodge Senate Leader, Presidential Foe". United States Senate. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ Lodge, Henry Cabot (1919). "Speech of Henry Cabot Lodge, Senator from Massachusetts In the Senate, August 12, 1919". The Treaty of Versailles: American Opinion. Boston: Old Colony Trust Company. p. 33.

- ^ Brands 2008, part 3 at 0:00.

- ^ John Milton Cooper, Woodrow Wilson (2009) 507–560

- ^ David Mervin, "Henry Cabot Lodge and the League of Nations." Journal of American Studies 4#2 (1971): 201-214.

- ^ Thomas A. Bailey, Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945)

- ^ Cooper, Woodrow Wilson, 544, 557–560; Bailey calls Wilson's rejection, "The Supreme Infanticide," Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945) p. 271

- ^ Edward C. Luck (1999). Mixed Messages: American Politics and International Organization, 1919–1999. Brookings Institution Press. p. 23. ISBN 0815791100. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ "The Washington Herald January 19,1921 p.1". Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ Raymond Leslie Buell, The Washington Conference Archived April 17, 2023, at the Wayback Machine (D. Appleton, 1922)

- ^ George E. Mowry, "Politicking in Acid," The Saturday Review October 3, 1953, p. 30

- ^ PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION AT A SPECIAL MEETING HELD JUNE 3, 1924., Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, June 3, 1924, p. 632, archived from the original on January 30, 2018, retrieved January 29, 2018

- ^ "Mount Lodge". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ^ Zimmermann 2002, p. 157.

- ^ Kathleen A. Gronnerud, "The Cabot Lodge Dynasty." in Modern American Political Dynasties: A Study of Power, Family, and Political Influence (2018): 25.

- ^ "LODGE, John Davis - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ Gronnerud, 25.

- ^ "Senator Lodge Suffers Shock in Hospital; Death May Come at Any Moment". The New York Times. November 6, 1924. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ "Senator Lodge Dies, Victim of Stroke, in his 75th Year". The New York Times. November 10, 1924. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ "Final Rites Said for Senator Lodge". The New York Times. November 13, 1924. p. 21. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

Further reading

edit- Adams, Henry (1911). The Life of George Cabot Lodge. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-8201-1316-6.

- Bailey, Thomas A. Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945), blames Wilson for the defeat of the Treaty.

- Brands, H. W. (March 11, 2008). Six Lessons for the Next President, Lesson 5: Leave Under a Cloud. Hauenstein Center at Grand Valley. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- Dotson, David Wendell. "Henry Cabot Lodge: A Political Biography, 1887-1901" (PhD dissertation, University of Oklahoma; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1980. 8024413).

- Eliot, Samuel (1911). "'Henry Cabot Lodge' (and 'Thomas Dixon Lockwood', 'John Davis Long')". Biographical Massachusetts; Biographies and Autobiographies of the Leading Men in the State, Volume 1. Boston: Massachusetts Biographical Society. OCLC 8185704.

- Fischer, Robert James. "Henry Cabot Lodge's Concept of Foreign Policy and the League of Nations" (PhD dissertation, University of Georgia; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1971. 7202483).

- Garraty, John A. (1953). Henry Cabot Lodge: A Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. the standard scholarly biography

- Garraty, John A. (February 2000). "Lodge, Henry Cabot". American National Biography. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- Grenville, John A. S. and George Berkeley Young. Politics, Strategy, and American Diplomacy: Studies in Foreign Policy, 1873-1917 (1966) pp 201–238 on "The Expansionist: The education of Henry Cabot Lodge"

- Gronnerud, Kathleen A. "The Cabot Lodge Dynasty." in Modern American Political Dynasties: A Study of Power, Family, and Political Influence (2018): 25+.

- Gwin, Stanford Payne. "The Partisan Rhetoric of Henry Cabot Lodge, Sr." (PhD dissertation, University of Florida; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1968. 6910929).

- Hewes, James E. Jr. (August 20, 1970). "Henry Cabot Lodge and the League of Nations". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 114 (4). American Philosophical Society: 245–255.

- Meyerhuber, Carl Irving Jr. "Henry Cabot Lodge, Massachusetts, and the New Manifest Destiny" (PhD dissertation, University of California, San Diego; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1972. 7310964). His policies in 1890s the response of Massachusetts interest groups.

- Robbins, Geraldine Andrews. "Woodrow Wilson encounters opposition to the League of Nations in the Senate: The question of Henry Cabot Lodge's role" (PhD dissertation, Chapman University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1971. EP30215).

- Sachs, Andrew Adam. "The imperialist style of Henry Cabot Lodge" (PhD dissertation, The University of Wisconsin-Madison; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1992. 9231221).

- Schriftgiesser, Karl (1946). The Gentleman from Massachusetts: Henry Cabot Lodge. Little, Brown and Company., a hostile biography

- Thomas, Evan. The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898 (Hachette Digital, 2010).

- Widenor, William C. Henry Cabot Lodge and the search for an American foreign policy (U. of California Press, 1983).

- Zimmermann, Warren (2002). First Great Triumph: How Five Americans Made Their Country a World Power. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-17939-5. Includes Lodge.

External links

edit- Works by Henry Cabot Lodge at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Cabot Lodge at the Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Cabot Lodge at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Library of Congress: "Today in History: May 12"

- For Intervention in Cuba (Archived February 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine)

- United States Congress. "Henry Cabot Lodge (id: L000393)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Henry Cabot Lodge at Find a Grave

- Newspaper clippings about Henry Cabot Lodge in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW