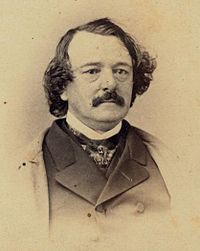

Henry Taylor Blow (July 15, 1817 – September 11, 1875) was a two-term U.S. Representative from Missouri and an ambassador to both Venezuela and Brazil.

Henry Taylor Blow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Commissioner of the District of Columbia[1] | |

| In office July 1, 1874 – December 31, 1874 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Seth Ledyard Phelps |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 2nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1863 – March 3, 1867 | |

| Preceded by | James S. Rollins |

| Succeeded by | Carman A. Newcomb |

| Member of the Missouri Senate | |

| In office 1854-1858 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 15, 1817 Southampton County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | September 11, 1875 (aged 58) Saratoga, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Unconditional Unionist, Republican |

| Spouse |

Minerva Grimsley Blow

(m. 1840) |

| Profession | Politician, businessman |

| Signature | |

Early life

editHenry was born in Southampton County, Virginia, to Captain Peter and Elizabeth (Taylor) Blow, owners of the famous enslaved man Dred Scott.[2] Blow was the eighth of ten children.[3] He moved with his parents to Huntsville, Alabama, where his father unsuccessfully tried farming.[2] In 1830 the family moved again to St. Louis, Missouri, where Peter Blow opened a boarding house, and hired out his slaves, including Dred Scott, who worked as a roustabout.[2] Henry's mother died in 1831, followed by his father the next year.[2]

Henry Blow graduated from Saint Louis University[4] and started apprenticing in a law office, but was forced by the deaths of his parents to become a clerk in his brother-in-law Charless' business, selling paint and oil.[5] Peter Blow had left his estate to his two unmarried daughters and Henry's younger brothers, Taylor and William. Henry was only fifteen when his father died, but that was old enough to be seen as a man able to survive on his own. Henry's married sister, Charlotte Taylor Blow, also did not receive an inheritance. She married Joseph Charless, Jr. in 1831. Charless' father, Joseph Charless, had founded the first newspaper west of the Mississippi. The Charless family helped Henry after the death of his father and Henry began working as a clerk at their wholesale drug and paint company. When Joseph Charles Sr. retired in 1836, Henry was made a partner in the business. In 1838, the business was renamed Charless, Blow, and Company. Only a few years later, in 1844, the partnership was dissolved. Charless retained ownership of the drugstore and Blow kept the manufacturing firm, which was later known as Collier White Lead and Oil Company. The Collier Company was one of the largest factories in St. Louis.[3]

Charless, Blow, and Company was not the only business that Blow would lead. Henry and his brother, Peter, created the Granby Mining and Smelting Company. Henry also served as president of the Iron Mountain Railroad for a time and helped to establish a furnace for the iron industry in Carondelet.[3]

Political life

editDespite being raised in the south, Blow was an abolitionist. Henry's parents had owned a slave, Dred Scott, who was sold to Dr. Emerson, who took Scott to Illinois and Wisconsin, which were both free territories. When Scott returned to St. Louis, Henry Taylor Blow encouraged Scott to sue for his freedom since he had lived in free states. Both men contributed money to finance the case, which made its way through the legal system, all the way to the Supreme Court. Scott later lost his bid for freedom. The court ruled that a slave is property and not a citizen. Dred Scott did eventually gain his freedom after Dr. Emerson's widow gave him to Taylor Blow, who freed Scott permanently.[3]

Blow joined the Republican Party in 1854 because of their views towards slavery.[3] Henry Taylor Blow was elected to the Missouri Senate that year and served from 1854 to 1858.[6] In 1860, Blow served as the Missouri delegate at the Chicago convention where they nominated Abraham Lincoln.[3]

Blow was appointed Minister to Venezuela in 1861 by President Abraham Lincoln, and served until the following year.[5] In this position Blow worked to improve trade between Venezuela and the Mississippi Valley. Blow did not retain this post for long. He returned to the United States to support the Union during the Civil War.[3] He was then elected to the United States House of Representatives[5] as an Unconditional Unionist. Blow was elected in 1862 and 1864 and served until 1867. Blow wanted to return to his businesses in St. Louis and declined to run for reelection in 1867.[3] Blow served on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Blow returned to politics in 1869 when he was appointed ambassador to Brazil by President Ulysses S. Grant. In 1874, Blow was appointed to the board of commissioners assigned to reorganize the government of the District of Columbia. He resigned, "for personal considerations," only 6 months after taking office.[3][7]

Personal life

editBlow married Minerva Grimsley (1821–1875), daughter of wealthy saddle manufacturer, Colonel Thornton and Susan (Stark) Grimsley,[2] by whom he had nine children. Henry and Minerva were married in 1840.[3]

Henry encouraged his daughters to get an education, which was unusual for that time.[3] One of them, Susan Elizabeth Blow, became a noted nineteenth-century educator[8] who started the nation's first all-district kindergarten.[9] In 1849, after the family's house had burned down and a cholera epidemic was sweeping St. Louis, Blow moved his family to Carondelet, which was a separate city at that time. Colonel Thornton had given the family seventeen acres there. Blow built a Victorian mansion on the land that held a library with elaborate paneling and stained glass windows that were later installed at the Missouri History Museum.[3]

Blow was a convert to Catholicism, and was responsible for Dred Scott being buried at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.[10]

Death and legacy

editHenry Taylor Blow died in 1875 at age 58 in Saratoga, New York.[11] Blow's death came just three months after Minerva's death. The two were married for 35 years.[3] Blow's funeral service lasted two hours and a special train was commissioned to take mourners from St. Louis to his home in Carondelet. The funeral procession was a mile long and spanned 25 miles to his final resting place.[3] He was interred in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri,[11] and was survived by six of his children.

Blow helped establish many organizations in St. Louis including a Presbyterian church, the Philosophical Society, the St. Louis Philharmonic Society, the Twentieth Century Club, the Western Academy of Art, and a Carondelet public school.[3]

Blow Street, which passes through several south St. Louis city neighborhoods, is named for Blow.[12]

The H.T. Blow School in Washington, DC was named for him. It was later merged with Franklin Pierce Elementary School to create Blow-Pierce Elementary. More recently it was changed to a charter school called Friendship Blow Pierce Elementary School.

References

edit- ^ Tindall, William (1903). Origin and Government of the District of Columbia. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 210. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Charles Van Ravenswaay, St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1764-1865, (Missouri Historical Society Press, 1991), 406.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Shepley, Carol Ferring (2008). Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine. St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri History Museum.

- ^ John Thomas Scharf, History of Saint Louis City and County: From the Earliest Periods to the Present Day, Volume 1, (Louis H. Everts & Co., 1883), 608.

- ^ a b c Walter Ehrlich, They Have No Rights, (Applewood Books, 2007), 10-11.

- ^ Charles Van Ravenswaay, St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1764-1865, 411.

- ^ "The Resignation of Commissioner Blow" (PDF). The Evening Star. January 5, 1875. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ Susan E. Blow, Kathleen G. Winterman, Encyclopedia of Educational Reform and Dissent, Vol. 1, (SAGE Publications Inc., 2010), 109.

- ^ Carol Ferring Shepley, Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery, (Missouri History Museum Press, 2008), 34.

- ^ "Why are Dred and Harriet Scott buried in different cemeteries? Curious Louis finds out". STLPR. December 2, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Carol Ferring Shepley, Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery, 37.

- ^ "St. Louis Public Library: Premier Library Sources". Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2014.