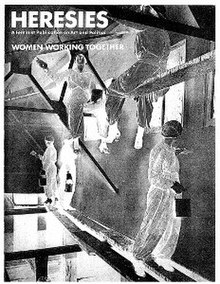

HERESIES: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics was a feminist journal that was produced from 1977 to 1993 by the New York–based Heresies Collective.

| |

| Publisher | Heresies Collective |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1977 |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | 1993 |

| Headquarters | New York |

| ISSN | 0146-3411 |

| OCLC number | 2917688 |

History

editHERESIES was a feminist magazine that published from 1977 to 1993, organized by a collective known as the Heresies Collective based in New York City.[1] Each of the 27 issues was collectively edited by a group of volunteers interested in a single topic under the guidance of the "mother collective"; each issue had its own style and perspective.[2] Subjects included feminist theory, art, politics, patterns of communication, lesbian art and artists, women's traditional arts and crafts, and politics of aesthetics, violence against women, working women, women from peripheral nations, women and music, sex, film, activism, racism, postmodernism, and coming of age.[3][4]

The journal was seen as not only a major contribution to the feminist art scene, but a major forum for feminist thinking that experimented with an editorial format that asked contributors to grapple with hierarchical and societal issues of difference. And it created a public discourse in feminist thought and expression. Initial members of the Heresies Collective included Joan Braderman, Mary Beth Edelson, Elizabeth Hess, Ellen Lanyon, Arlene Ladden, Lucy R. Lippard, Marty Pottenger, Miriam Schapiro and May Stevens.[5][6][failed verification] The last issue, LATINA - A Journal of Ideas, was published in 1993.

Voice

editHearing from individual voices was central to the publications overall goal. Being silenced by the patriarchy and anti-feminism movements at the time the women of the publication hoped to use each issue to voice their thoughts on everyday topics and important matters. Each issue was compiled by a different group of women by the Mother Collective. The first issue titled "Feminism, Art, and Politics" provided pages for the women to detail their initial hopes for the magazine and personal thoughts on feminism.[7]

Collectivity

editAs individual voices expressed their values within the patriarcal society, a collaborative effort was also valued to show how these women could work as a system to counteract the discrimination they received. The collective functioned as an egalitarian system that abolished the idea of a hierarchy and the idea that some voices were more important than others. In modeling a new structure for working together, Heresies emphasized a cultures that would provide women with real alternatives to the patriarchal structures experienced on a daily basis.[7]

Artistry

editTo fully communicate feminist ideologies and individual voices art works and pieces were published within each issue of Heresies. Through their works the women hoped to push back on the prestigious, male dominated art scene at the time.[7] Their artistry also pushed to challenge dominant practices employed by popular magazines at the time. Through inexpensive methods of collaging, sewing, and appliquéing the women allowed themselves full artistic expression and creative freedom. Additionally the artists hoped to reclaim these methods historically assigned to women and deemed as unprofessional.[7]

The art work and pieces created by the women were all hand made both by individuals and through a collaborative effort. Rather than focusing on a finished product, the publication valued the rough, D.I.Y. in order to gain a sense of an artist's process through their work. An inside look into their technique additionally was used to communicate to their audience that anyone is capable of creativity.[7]

Reader Collaboration

editIssue fourteen titled "The Women's Pages" marked as unique issue among the history of the publication. One page of the issue was intentionally left blank, encouraging readers to contribute their own works of art and literature. In the editorial statement the collective voiced that the blank page acted as an effort to create a one of a kind issue for each individual.[7] This single page reflected the overall mission of the collective to include all voices and empower their audience. Readers contributing to the page were able to act on their creativity and become a part of the feminist movement.

Controversies

editThe Mother Collective were a group of women central to overseeing the publication and held responsibility for creating the topics for each issue. The collective recruited specific writers and artists they felt could carry out and address the concerning subject. However through their leadership role these women were often called out for their lack of diversity in comprising only white women.[7]

The concern for the lack of diversity was initially ignited after the publication of the third issue “Lesbian Art and Artists”. The issue was published in 1977 and was praised for creating a safe space in allowing women to express their sexuality through their work. Enduring homophobia and marginalization from the hegemonic heterosexual culture the issue provided a platform lesbian women were otherwise unable to have.[8] As a preliminary statement the issue included an acknowledgment of their biases,"We are all lesbians, white, college-educated, and mostly middle class women who live in New York and have a background in the arts".[8]

Regardless, the issue received criticism for failing to include lesbian artists of color. Combahee River Collective, a black feminist organization, wrote the all-white editorial group demanding the oversight be addressed. The letter was published by the Heresies Collective as a gesture of accountability. Additionally, to be more inclusive and focus on the subject of race, Heresies published the issues "Third World Women" and "Racism is the Issue". However, their initial lack of intersectionality in "Lesbian Art and Artists" remained as a major fault throughout the history of the publication.

Members of the Mother Collective

editAround nineteen women were founders:[9]: 38–50

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Women's History Month: Heresies Magazines". amUSIngArtifacts. 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Exhibition: Heresies Magazine (1977-1993)". The University of Victoria Libraries. Fall 2017.

- ^ Napikoski, Linda. "Heresies A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics". About.com.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Meagher, Michelle (2014). "Difficult, Messy, Nasty, and Sensational". Feminist Media Studies. 14 (4): 578–592. doi:10.1080/14680777.2013.826707. S2CID 142109461.

- ^ "the Heretics". The Heretics Film Project.

- ^ Rickey, Carrie (1996). "Writing (and Righting) Wrongs: Feminist Art Publications". In Broude, Norma; Goddard, Mary D. (eds.). The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 126. ISBN 0810926598.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Heresies Magazine (1977-1993) · Movable Type: Print Material in Special Collections · UVic Libraries Omeka Classic". omeka.library.uvic.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-06.

- ^ a b Burk, Tara (Fall–Winter 2013). "In Pursuit of the Unspeakable: Heresies' 'Lesbian Art and Artists' Issue, 1977". Women's Studies Quarterly. 41 (3–4): 63–78. doi:10.1353/wsq.2013.0098. S2CID 83999988 – via General OneFile.

- ^ Moore, Sabra (2016). "Chapter 3: We Must Have Theory & Practice & Many Meetings". Openings: A Memoir from the Women's Art Movement, New York City 1970-1992. New Village Press. ISBN 9781613320181.

Further reading

edit- Tobin, Amy (18 October 2019). "Heresies: Collaboration and Dispute in a Feminist Publication on Art and Politics". Women: A Cultural Review. 30 (3): 280–296. doi:10.1080/09574042.2019.1653118. S2CID 211411926.

External links

edit- Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, archive of past issues

- Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, collection on archive.org

- "The Heretics." MoMA documentary

- "Synopsis: The Heretics."

- Issue 14