The Sword in the Stone is a 1963 American animated musical fantasy comedy film produced by Walt Disney and released by Buena Vista Distribution. It is based on the novel of the same name by T. H. White, first published in 1938 and then revised and republished in 1958 as the first book of White's Arthurian tetralogy The Once and Future King. Directed by Wolfgang Reitherman, the film features the voices of Rickie Sorensen, Karl Swenson, Junius Matthews, Sebastian Cabot, Norman Alden, and Martha Wentworth. It was the last animated film from Walt Disney Productions to be released in Walt Disney's lifetime.[3][4][5]

| The Sword in the Stone | |

|---|---|

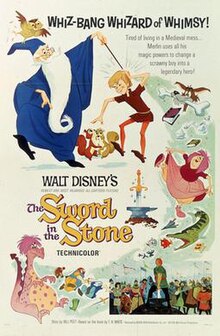

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Wolfgang Reitherman |

| Story by | Bill Peet |

| Based on | The Sword in the Stone by T. H. White |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Starring |

|

| Edited by | Donald Halliday |

| Music by | George Bruns |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 79 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million[1] |

| Box office | $22.2 million (United States and Canada)[2] |

Disney first acquired the film rights to the novel in 1939, and there were various attempts at developing the film over the next two decades before production on the film officially began. Bill Peet wrote the story for the film, while the songs were written by the Sherman Brothers. This was the first animated Disney film to feature songs by the Sherman Brothers; they went on to contribute music to such Disney animated feature films as Mary Poppins (1964), The Jungle Book (1967), The Aristocats (1970), and The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1977). George Bruns composed the film's score, following his work on the previous two animated Disney films, Sleeping Beauty (1959) and One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). He also composed the scores of the next three Disney animated feature films, The Jungle Book, The Aristocats, and Robin Hood (1973).

The Sword in the Stone premiered in London on December 12, 1963, and was theatrically released in the United States on December 25. The film received mixed reviews from critics, but it became a box-office success, grossing $22.2 million in the United States and Canada.

Plot

editAfter the King of England, Uther Pendragon, dies without an heir to his throne, a sword magically appears inside an anvil atop a stone, with an inscription proclaiming that whoever removes it will be the future king. Many have unsuccessfully attempted to remove the sword, and the sword becomes forgotten, leaving England in the Dark Ages.

Years later, an 11-year-old orphan named Arthur, commonly called Wart, accidentally scares off a deer his older foster brother Sir Kay was hunting, causing Kay to launch his arrow into the forest. While retrieving the arrow, Arthur meets Merlin, an elderly wizard who lives with his talking pet owl Archimedes. Merlin declares himself Arthur's tutor and returns with him to his home, a castle run by Sir Ector, Arthur's foster father. Ector's friend, Sir Pelinore, arrives to announce that the winner of the upcoming New Year's Day tournament in London will be crowned king. Ector decides Kay will be a contender and appoints Arthur as Kay's squire.

To educate Arthur, Merlin transforms them both into fish. They swim in the castle moat to learn about physics, until an angry pike attacks the pair. After the lesson, Arthur is sent to the kitchen as punishment for attempting to relate what happened to Ector and Kay. Merlin enchants the dishes to wash themselves, then takes Arthur out again for another lesson.

For the next lesson, Merlin transforms them both into squirrels to learn about gravity. Arthur almost gets eaten by a wolf, but is saved by a female squirrel who falls in love with him. After they return to human form, Ector accuses Merlin of using black magic on the dishes. Arthur defends Merlin, but Ector punishes Arthur by giving Kay another squire, Hobbs.

Resolving to make amends, Merlin plans on educating Arthur full-time, but Merlin's knowledge of future history confuses Arthur, prompting Merlin to appoint Archimedes as Arthur's teacher. Merlin transforms Arthur into a sparrow and Archimedes teaches him how to fly. Soon after, Arthur encounters Madam Mim, an eccentric, evil witch who is Merlin's nemesis. Merlin arrives to rescue Arthur before Mim can destroy him, and Mim challenges Merlin to a wizards' duel. Despite Mim's cheating, Merlin outsmarts her by transforming into a germ and infecting her, illustrating the importance of knowledge over strength.

On Christmas Eve, Kay is knighted. When Hobbs comes down with the mumps, Ector reinstates Arthur as Kay's squire, which spurs him to happily break the news to his teachers. Archimedes congratulates him, but Merlin, thinking Arthur is forsaking education, rebukes him for staying under Kay's thumb. When Arthur retorts that he's lucky, Merlin angrily transports himself to 20th-century Bermuda.

At the tournament, Arthur realizes he left Kay's sword at the inn. It is closed for the tournament, but Archimedes sees the "Sword in the Stone", which Arthur removes almost effortlessly, unknowingly fulfilling the prophecy. When Arthur returns with the sword, Ector recognizes it and the tournament is halted. Ector places the sword back in its anvil, demanding Arthur prove that he pulled it. He pulls it once again, revealing that he is England's rightful king, earning Ector and Kay's respect and the former's apology.

Later, the newly crowned King Arthur sits in the throne room with Archimedes, feeling unprepared for the responsibility of ruling a country. Merlin returns from Bermuda and resolves to help Arthur become the great king he has foreseen him to be and ensure his legacy.

Voice cast

edit- Sebastian Cabot as Sir Ector,[6] Arthur's foster father and Kay's father. Though he clearly cares for Arthur, he often treats him more like a servant than a son.

- Cabot was also the film's narrator.

- Karl Swenson as Merlin, an old and eccentric wizard who aids and educates Arthur.

- Rickie Sorensen, Richard Reitherman, and Robert Reitherman as Arthur (aka Wart), the boy who will grow up to become the legendary British leader King Arthur.

- Junius Matthews as Archimedes, Merlin's crotchety, yet highly educated, pet owl and servant, who has the ability to speak.

- Ginny Tyler as the Little Girl Squirrel[7] who immediately develops an attraction to Arthur upon encountering him as a squirrel.

- Martha Wentworth as Madam Mim, a black magic-proficient witch and Merlin's nemesis. Mim's magic uses trickery, as opposed to Merlin's scientific skill.

- Wentworth also voiced the Granny Squirrel, an elderly squirrel who is attracted to Merlin while Merlin is a squirrel.

- Norman Alden as Sir Kay,[8] Arthur's morose and inept older foster brother and Ector's son. Unlike his father, he has much less regard for Arthur and thinks little good of him.

- Alan Napier as Sir Pelinore,[9] Ector's friend, who announces the jousting tournament.

Thurl Ravenscroft voiced Sir Bart, one of the knights seen at the jousting tournament. Jimmy MacDonald voiced the Wolf who has several encounters with Arthur and attempts to eat him, but is constantly met with misfortune. Martha Wentworth and Barbara Jo Allen voiced the Scullery Maid who works in Ector's castle and believes Merlin to be an evil sorcerer. Tudor Owen voiced one of the knights or nobles in the crowd during the tournament.

Production

editDevelopment

editIn early 1939, Walt Disney purchased the film rights to T. H. White's The Sword in the Stone, which he revealed in February.[10] Following the outbreak of World War II, the studio focused instead on producing cartoons for the United States government and armed forces such as Der Fuehrer's Face (1943). In June 1944, following the successful re-release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Disney assigned writers to work on The Sword in the Stone, along with Cinderella (1950) and Alice in Wonderland (1951).[11] It continued to be announced that the project was in active development throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s.[12][13] In June 1960, Disney told the Los Angeles Times that, following the release of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, two animated projects were in development, which were Chanticleer and The Sword in the Stone.[14] Around that same time, Disney's elder brother Roy O. Disney attempted to persuade him to discontinue their feature animation division, as enough films remained to make successful re-releases. The younger Disney refused, but because of his plans to build another theme park in the United States, he would approve only one animated film to be released every four years.[15]

Chanticleer was developed by Ken Anderson and Marc Davis, who aimed to produce a feature animated film in a more contemporary setting. They visited the Disney archives and decided to work on adapting the satirical tale after glancing at earlier conceptions dating back to the 1940s.[16] Anderson, Davis, Milt Kahl, and director Wolfgang Reitherman spent months preparing elaborate storyboards for Chanticleer. Following a silent response to one pitch presentation, a voice from the back of the room said, "You can't make a personality out of a chicken!"[17] When the time came to approve either Chanticleer or The Sword in the Stone, Disney remarked that the problem with making a rooster a protagonist was, "[you] don't feel like picking a rooster up and petting it."[18]

Meanwhile, The Sword in the Stone was developed solely by veteran story artist Bill Peet. After Disney had seen the 1960 Broadway production of Camelot, he approved the project to enter production.[19] Ollie Johnston stated that "[Kahl] got furious with Bill for not pushing Chanticleer after all the work he had put in on it. He said, 'I can draw a damn fine rooster, you know'. Bill said, 'So can I.'"[20] Peet recalled about "how humiliated they were to accept defeat and give in to The Sword in the Stone... He allowed them to have their own way, and they let him down. They never understood that I wasn't trying to compete with them, just trying to do what I wanted to work. I was [in] the midst of all this competition, and with Walt to please too."[21]

Writing in his autobiography, Peet said he decided to write a screenplay before producing storyboards, though he found the narrative "complicated, with the Arthurian legend woven into a mixture of other legends and myths" and that finding a direct storyline required "sifting and sorting".[22] After Disney received the first screenplay draft, he told Peet that it should have more substance. Peet lengthened his second draft by elaborating on the more dramatic aspects of the story, which Disney approved of through a phone call from Palm Springs, Florida.[22]

Casting

editRickie Sorensen, who was cast as Arthur, entered puberty during the film's production. This forced director Wolfgang Reitherman to cast two of his sons, Richard and Robert, to replace him.[23][24] This resulted in Arthur's voice noticeably changing between scenes, and sometimes within the same scene. The three voices also portray Arthur with an American accent, sharply contrasting with the English setting and the accents spoken by most of the other characters.[25] Mari Ness of the online magazine Tor.com suggested, "given that the film is about growing up, this problem might have been overcome" with the three voices being interpreted as symbolizing Arthur's mental and physical development. However, she noted "[Reitherman] inexplicably chose to leave all three voices in for some scenes, drawing attention to the problem that they were not the same actor."[25]

Furthermore, Reitherman estimated that 70 actors read for the part of Merlin, but none of them had eccentricity that he was looking for. Karl Swenson initially read for Archimedes, but he was instead cast as Merlin.[23]

Animation

editThe film continued the Xerox method of photocopying drawings onto animation cels that had been used in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). An additional animation technique, "touch-up", was created during production to replace the clean-up process. The clean-up process had required assistant animators to transfer the directing animators' sketches onto new sheets of paper, which were then copied onto the animation cels. To do a touch-up, the assistants would instead draw directly on the animators' sketches. This streamlined the process, but it also caused assistants of directing animator Milt Kahl to fear they would ruin his linework.[26]

Animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston were proud of their work on the final film and stated on their website that "Some of our best animation is scattered throughout this lively film. "[27]

Release

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

The Sword in the Stone premiered in London on December 12, 1963. It was released to theaters on December 18 in the United Kingdom and on December 25 in the United States. It was re-released on December 22, 1972. The film was again re-released to theaters on March 25, 1983, as a double bill with the animated short Winnie the Pooh and a Day for Eeyore.

Home media

editThe Sword in the Stone was released on North American VHS, Betamax, and Laserdisc in 1986 as an installment of the Walt Disney Classics collection.[28] It was re-released on VHS in 1989[29] and on VHS and Laserdisc on July 12, 1991.[30] It was first released on VHS in the United Kingdom in 1988, followed by a re-issue the following year. Another re-release on VHS and Laserdisc occurred on October 28, 1994, this time as part of the Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection.

The film was released on VHS and DVD on March 20, 2001, as an installment in the Walt Disney Gold Classic Collection. The VHS edition included the Goofy short A Knight for a Day while the DVD contained the Mickey Mouse short Brave Little Tailor, the episode "All About Magic" from the Disneyland television program, and film facts.[31] The DVD of the film was re-released as a 45th-anniversary special edition on June 17, 2008.[32]

For its 50th anniversary, the film was released on Blu-ray on August 6, 2013.[33] Despite being touted as a new remaster of the film, this release was heavily criticized by home media reviewers for the "scrubbed" quality of its digital transfer due to the excessive use of noise reduction.[34][35][36][37]

Reception

editBox office

editDuring its initial release, The Sword in the Stone earned an estimated $4.75 million in box office rentals in the United States and Canada.[38] It garnered $2.5 million in box office rentals during its 1972 re-release[39] and $12 million during its 1983 re-release.[40] The film has had a lifetime domestic gross of $22.2 million in North America.[2]

Critical reception

editThe Sword in the Stone received mixed reviews from critics, who thought that its humor failed to balance out a "thin narrative".[41] Gene Arneel of Variety wrote that the film "demonstrates anew the magic of the Disney animators and imagination in character creation... But one might wish for a script which stayed more with the basic story line rather than taking so many twists and turns which have little bearing on the tale about King Arthur as a lad."[42] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised the film, claiming it is "an eye-filling package of rollicking fun and thoughtful common sense. The humor sparkles with real, knowing sophistication — meaning for all ages — and some of the characters on the fifth-century landscape of Old England are Disney pips."[43] Philip K. Scheuer, reviewing for the Los Angeles Times, described the film as "more intimate than usual with a somewhat smaller cast of characters—animal as well as human. Otherwise, the youngsters should find it par the usual Disney cartoon course. It may not be exactly what T. H. White had in mind when he wrote this third of his sophisticated trilogy about King Arthur, but it's a good [bit] livelier than the stage Camelot derived from another third."[44]

On the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 68% based on 31 reviews, with an average score of 6/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "A decent take on the legend of King Arthur, The Sword in the Stone suffers from relatively indifferent animation, but its characters are still memorable and appealing."[45] Nell Minow of Common Sense Media gave the film four out of five stars, writing that "delightful" classic brings Arthur legend to life.[46] In his book The Best of Disney, Neil Sinyard states that, despite not being well known, the film has excellent animation, a complex structure, and is actually more philosophical than other Disney features. Sinyard suggests that Walt Disney may have seen something of himself in Merlin, and that Mim, who "hates wholesome sunshine", may have represented critics.[41]

Accolades

editIn 1964, The Sword in the Stone was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Scoring of Music—Adaptation or Treatment. It lost the award to Irma la Douce (1963).[47]

In 2008, The Sword in the Stone was one of the 50 films nominated for the American Film Institute's Top 10 Animated Films list, but it was not selected as one of the top 10.[48]

Music

editOriginal songs performed in the film include:

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Sword in the Stone" (Fred Darian) | |

| 2. | "Higitus Figitus" (Karl Swenson) | |

| 3. | "That's What Makes the World Go Round" (Karl Swenson & Rickie Sorensen) | |

| 4. | "A Most Befuddling Thing" (Karl Swenson) | |

| 5. | "Mad Madam Mim" (Martha Wentworth) | |

| 6. | "Blue Oak Tree" (Sebastian Cabot & Alan Napier) |

Deleted songs from the film include:

- "The Magic Key"

- "The Sand of Time"

- "Blue Oak Tree" (just the ending was included in the film)

Legacy

editSeveral characters from the film made frequent appearances in the House of Mouse television series. Merlin was voiced by Hamilton Camp, and appears in the episode "Rent Day". Wart also made a few appearances in the series, usually seen in crowd shots with Merlin. He also appears with Merlin in the audience in the episode "Mickey vs. Shelby" after the cartoon ends. Sir Kay was seen in the episode "Ask Von Drake", when he tries to pull the sword from the stone with Arthur, Merlin, and Madam Mim. Madam Mim appears as a villain in the spin-off film Mickey's House of Villains. In the past, Merlin frequented the Disney Parks, the only character from the film appearing occasionally for meet-and-greets at Disneyland Resort and Walt Disney World Resort. He appeared in the opening unit of Walt Disney's Parade of Dreams at Disneyland Park. He also hosts the Sword in the Stone ceremony in the King Arthur Carrousel attraction in Fantasyland at Disneyland. In 2014 and 2015, UK health directive Change4Life incorporated "Higitus Figitus" as the soundtrack for adverts promoting their Disney-sponsored "10 minute shake up" summer program.

Comics

editIn the Disney comics, Madam Mim was adopted into the Donald Duck universe, where she sometimes teams with Magica De Spell, Witch Hazel and/or the Beagle Boys.[49] She also appeared in the Mickey Mouse universe, where she teamed with Black Pete on occasion and with the Phantom Blot at one point. She was in love with Captain Hook in several stories; in others, with Phantom Blot. In the comics produced in Denmark or in the Netherlands, she lost her truly evil streak, and appears somewhat eccentric, withdrawn and morbid, yet relatively polite.

Mim appeared in numerous comics produced in the United States by Studio Program in the 1960s and 1970s,[50] often as a sidekick of Magica. Most of the stories were published in Europe and South America. Among the artists are Jim Fletcher, Tony Strobl, Wolfgang Schäfer, and Katja Schäfer. Several new characters were introduced in these stories, including Samson Hex, an apprentice of Mim and Magica.[51]

Merlin (Italian: Mago Merlino), Archimedes (Italian: Anacleto) and Mim (Italian: Maga Magò)'s debut in the prolific Italian Disney comics scene was in a greatly remembered story: "Mago Merlino presenta: Paperino e la 850" (lit. 'The Wizard Merlin presents: Donald Duck and the 850'), published in nine parts in Topolino "libretto" #455-#464 (16 August-18 October 1964). In the story, Scrooge McDuck charged Donald Duck and Huey, Dewey and Louie with delivering a special gas to power the Olympic torch at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, passing through the World's most disparate climates to test its properties. However, Donald's car, the 313, breaks down, but Merlin materializes and magically creates a Fiat 850 (Fiat was sponsoring the story). Mim, however, wants to obtain the gas, and has the Beagle Boys chase after them. The 850 (initially put in contrast with the villains' generic, Edsel-like car), thanks to Merlin's magic, displays remarkable characteristics that help the ducks successfully finish their mission.

Video games

editMadam Mim made a surprise appearance in the video game World of Illusion as the fourth boss of the game.

Merlin is a supporting character in the Kingdom Hearts series.[52] In Kingdom Hearts, Merlin, who lives in an abandoned shack in Traverse Town with Cinderella's Fairy Godmother, is sent by King Mickey to train Sora, Donald, and Goofy in the art of magic. He owns an old book that features the world of The Hundred Acre Wood, home of Winnie the Pooh. The book's pages, however, have been torn out and scattered across the universe, so Merlin asks Sora to retrieve them for him.

In Kingdom Hearts II, Merlin, now voiced by Jeff Bennett,[53] has moved to Hollow Bastion to aid Leon's group as part of the town's restoration committee, though he is at odds with Cid, who prefers his own computer expertise over Merlin's magic. Merlin again instructs Sora, Donald, and Goofy in the art of magic, and again requests that they retrieve the stolen parts of the Pooh storybook. At one point in the game, he is summoned to Disney Castle by Queen Minnie to counter the threat of Maleficent, and he constructs a door leading to Disney Castle's past (Timeless River) for the trio to explore and stop Maleficent and Pete's plans.

In the prequel, Kingdom Hearts Birth by Sleep, Merlin encounters Terra, Aqua, and Ventus and grants them each access to the Hundred Acre Wood. The prequel also reveals that it was Terra who gave him the book in the first place after finding it in Radiant Garden. According to series creator Tetsuya Nomura, a world based on The Sword in the Stone was initially to appear in Kingdom Hearts 3D: Dream Drop Distance, but the idea was scrapped. Merlin returns in Kingdom Hearts III, where he asks Sora to restore Pooh's storybook once more (though this does not involve finding any missing pages), but has no involvement in the story beyond that, and instead spends his time at Remy's bistro in Twilight Town having tea.

Merlin appears in the world builder video game Disney Magic Kingdoms as the guide for the player during the game progress, and as the owner of Merlin's Shop, where the players can buy and sell in-game items, as well as other options that Merlin can perform.[54] In a November 2023 update to that game, Merlin became a fully playable character, while Arthur was also added to the game; both were done in celebration of the film's 60th anniversary.[55] Merlin also appears as one of the villagers in Disney Dreamlight Valley, filling a similar role as a guide who teaches the player new mechanics during the early portions of the game.

Live-action film adaptation

editA live-action feature film adaptation entered development in July 2015, with Bryan Cogman writing the script and Brigham Taylor serving as producer.[56] By January 2018, Juan Carlos Fresnadillo was announced as director.[57] The next month, the film was revealed to premiere exclusively on Disney+.[58] Enrique Chediak joined to serve as the cinematographer in September,[59] while Eugenio Caballero joined as the production designer in December.[60]

Set in Stone

editAn alternate-scenario young adult novel, Set in Stone, part of the A Twisted Tale series, was released in 2023. It tells of an alternate scenario that shows what might have happened if it was Madam Mim's magic that helped Arthur draw the sword from the stone.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Thomas, Bob (November 1, 1963). "Walt Disney Eyes New Movie Cartoon". Sarasota Journal. p. 22. Retrieved June 5, 2016 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ a b "Box Office Information for The Sword in the Stone". The Numbers. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Trimborn, Harry (1966-12-16). "Wizard of Fantasy Walt Disney Dies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-11-03.

- ^ Cooke, Alistair (2011-12-16). "The death of Walt Disney — folk hero". The Guardian. Retrieved 2024-11-03.

- ^ "Walt Disney, 65, Dies on Coast". The New York Times. 16 December 1966.

- ^ Smith, Dave. ""The Sword in the Stone" Movie History". Disney Archives. Archived from the original on March 31, 2010. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ "Sights & Sounds at Disney Parks: Remembering Disney Legend Ginny Tyler". Disney Parks Blog. July 23, 2012. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Slotnik, Daniel E. (August 1, 2012). "Norman Alden, a Character Actor for 50 Years, Is Dead at 87". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ "The Sword in the Stone | Disney Movies". movies.disney.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ "Story Buys". Variety. February 1, 1939. p. 20. Retrieved December 26, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Disney Writers Prep for Trio of New Features". Variety. June 28, 1944. p. 3. Retrieved December 26, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (November 22, 1948). "Walt Disney Commences Scouting for 'Hiwatha'; Iturbi Term Deal Sealed". Los Angeles Times. Part I, p. 27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (November 25, 1960). "Walt Disney Plans 'Sleeping Beauty' Film". Los Angeles Times. Part II, p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (June 25, 1960). "Realist Disney Held His Dreams". Los Angeles Times. Section G, p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hill, Jim (December 31, 2000). "The "Chanticleer" Saga -- Part 2". Jim Hill Media. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Hill, Jim (December 31, 2000). "The "Chanticleer" Saga -- Part 3". Jim Hill Media. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Solomon, Charles (1995). The Disney That Never Was: The Stories and Art of Five Decades of Unproduced Animation. Hyperion Books. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-786-86037-1.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (2008). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. University of California Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-520-25619-4.

- ^ Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-556-52591-9. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Canemaker, John (1999). Paper Dreams: The Art And Artists Of Disney Storyboards. Disney Editions. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-786-86307-5.

- ^ "Seldom Re-Peeted: The Bill Peet Interview". Hogan's Alley (Interview). Interviewed by John Province. May 10, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Peet, Bill (1989). Bill Peet: An Autobiography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 168–71. ISBN 978-0-395-68982-0.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (December 28, 1963). "Changing Voices a Problem". Evening Independent. p. 8-A. Retrieved June 5, 2016 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Hischak, Thomas (September 21, 2011). Disney Voice Actors: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland & Company. p. 176. ISBN 978-0786462711. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Ness, Mari (August 6, 2015). "In Need of a Villain: Disney's The Sword in the Stone". Tor.com. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Korkis, Jim (November 8, 2017). "Floyd Norman Remembers The Sword in the Stone: Part Two". MousePlanet.

- ^ "Feature Films". Frank and Ollie. Archived from the original on November 21, 2005. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ "Disney Putting $6 Million Behind Yule Campaign". Billboard. Vol. 98, no. 32. August 9, 1986. pp. 1, 84. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Zad, Martie (September 27, 1989). "'Bambi' Released in Video Woods". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ McCullagh, Jim (May 18, 1991). "'Robin' To Perk Up Midsummer Nights" (PDF). Billboard. p. 78. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Sword in the Stone — Disney Gold Collection". Disney.go.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2001. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon.com: The Sword in the Stone (45th Anniversary Special Edition): Norman Alden, Sebastian Cabot, Junius Matthews, The Mello Men, Alan Napier, Rickie Sorenson, Karl Swenson, Martha Wentworth, Barbara Jo Allen, Vera Vague, Wolfgang Reitherman: Movies & TV". Amazon. June 17, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ "Amazon.com: The Sword in the Stone (50th Anniversary Edition)". Amazon.com. August 6, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Kenneth (August 1, 2013). "The Sword in the Stone Blu-ray Review". Blu-ray.com. Blu-ray.com, Inc. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Jane, Ian (August 6, 2013). "Sword in the Stone, The". DVD Talk. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Salmons, Tim (September 3, 2013). "Sword in the Stone, The: 50th Anniversary Edition". The Digital Bits. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Peck, Aaron (August 19, 2013). "The Sword In The Stone: 50th Anniversary Edition". High Def Digest. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Big Rental Pictures of 1964". Variety. January 6, 1965. p. 39 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973". Variety. January 19, 1974. p. 60.

- ^ "The Sword in the Stone (Re-issue)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Sinyard, Neil (1988). The Best of Disney. Portland House. pp. 102–105. ISBN 0-517-65346-X.

- ^ Arneel, Gene (October 2, 1963). "Film Reviews: The Sword in the Stone". Variety. p. 6. Retrieved February 5, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (December 26, 1963). "Screen: Eight New Movies Arrive for the Holidays". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (December 25, 1963). "'Sword in the Stone' Lively Cartoon Feature". Los Angeles Times. Part V, p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Sword in the Stone (1963)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ Minow, Nell. "The Sword in the Stone – Movie Review". Common Sense Media. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ "The 36th Academy Awards (1964)". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 5 October 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ Wells, John (2015). American Comic Book Chronicles: 1960-64. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 978-1605490458.

- ^ First is in S 65051, according to the Inducks.

- ^ "Samson Hex - I.N.D.U.C.K.S." coa.inducks.org.

- ^ Square (November 15, 2002). Kingdom Hearts (PlayStation 2). Square Electronic Arts.

- ^ Square (December 22, 2005). Kingdom Hearts II (PlayStation 2). Square Electronic Arts.

- ^ "Update 9: Beauty and the Beast | Livestream". YouTube. March 3, 2017.

- ^ "Patch Notes – Update 76 The Sword in the Stone". disney-magic-kingdoms.com. Gameloft. Archived from the original on November 10, 2023. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Kit, Borys (July 20, 2015). "'Sword in the Stone' Live-Action Remake in the Works With 'Game of Thrones' Writer (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Kit, Borys (January 19, 2018). "Disney's 'Sword in the Stone' Live-Action Remake Finds Director (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (February 8, 2018). "Disney Unveils Inaugural Streaming Service Launch Slate To Town; No R-Rated Fare". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ Marc, Christopher (September 18, 2018). "Disney's Live-Action 'Sword In The Stone' Movie Adds 'Bumblebee/28 Weeks Later' Cinematographer". Geeks WorldWide. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ Marc, Christopher (December 2, 2018). "'Pan's Labyrinth' Production Designer Confirmed To Work On Disney's Live-Action 'The Sword In The Stone' Movie". HN Entertainment. Retrieved December 31, 2018.