The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act 1856, also Act XV, 1856, passed on 16 July 1856, legalised the remarriage of widows in all jurisdictions of India under East India Company rule. The law was enacted on 26 July 1856.[1] It was drafted by Lord Dalhousie and passed by Lord Canning before the Indian Rebellion of 1857. It was the first major social reform legislation after the abolition of sati pratha in 1829 by Lord William Bentinck.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

| Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856 | |

|---|---|

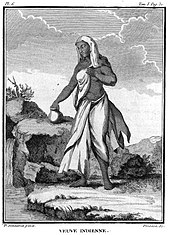

A widow in India (seen in this engraving from 1774–1781) was not allowed to wear a blouse or choli under her sari. The sari was required to be of coarse cloth, preferably white. | |

| |

| Repealed by | |

| THE WIDOWS' RE-MARRIAGE (REPEAL) ACT, 1983 | |

| Status: Repealed |

To protect what it considered family honour and family property, Hindu society had long disallowed the remarriage of widows, even child and adolescent ones, all of whom were expected to live a life of austerity and abnegation.[8] The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856,[9] provided legal safeguards against loss of certain forms of inheritance for remarrying a Hindu widow,[8] though, under the Act, the widow forsook any inheritance due her from her deceased husband.[10] Especially targeted in the act were child widows whose husbands had died before consummation of marriage.

Vidyasagar's argument based on Hindu Dharma Sastras

editIshwar Chandra Vidyasagar, a Brahmin and a Sanskrit scholar was the most prominent campaigner of widow remarriage. He petitioned the Legislative council,[11] but there was a counter petition against the proposal with nearly four times more signatures by Radhakanta Deb and the Dharma Sabha.[12][13] Even though Vidyasagar faced huge opposition from Hindu orthodox groups, he put use of his prodigious knowledge of Sanskrit to make an exhaustive search of authentic Hindu scriptures on law (i.e. Dharma sastras) to find support for his cause of widow remarriage. He stumbled upon a few verses in Parasara Smriti written by sage Parashara, which supported widow remarriage.

Author Subal Chandra Mitra, writer of biography of Vidyasagar in 1902, mentions that moment of Vidyasagar's response: "After infinite toil and pains, one night, he suddenly bounced up in ecstasy and cried out loudly: — 'I have, at last, found it.'." [sic][14] The verse is

Naṣṭe mṛte praprajite klibeca patite patau

Pañcasvāpatsu nārīṅāṃ patiranyo vidhīyate (Parāśara smṛti 4-30)[15][16]

"1. On loss of a husband who went abroad, 2. on his death, 3. on his turning into a Sanyasi, 4. on his being an impotent, or 5. on his sinful degradation, — under any one of these five calamities, it is sanctioned for (those) women to take another husband."

Based on the above evidence, Vidyasagar made a convincing argument that sage Parashara suggested three choices for a widow, the first one to remarry, second one to remain celibate and the last one to perform Sahagamana. While the second choice was extremely tough in Kali yuga, final one got already banned by British and therefore only prevailing option is the first choice as suggested by Parashara, i.e. to remarry.[17]

"Second marriages, after the death of the husband first espoused, are wholly unknown to the Law; though in practice, among some communities, nothing is so common."[1]

— William Hay Macnaghten (1862)

"The problem of widows—and especially of child widows—was largely a prerogative of the higher Class people among whom child marriage was practised and remarriage prohibited. Irrevocably, eternally married as a mere child, the death of the husband she had perhaps never known left the wife a widow, an inauspicious being whose sins in a previous life had deprived her of her husband, and her parents-in-law of their son, in this one. Doomed to a life of prayer, fasting, and drudgery, unwelcome at the celebrations and auspicious occasions that are so much a part of many communities of any religion family and community life, her lot was scarcely to be envied.

On the other hand, particularly Sudra caste and dalits —who represented approximately 80 percent of the Hindu population—neither practised child marriage nor prohibited the remarriage of widows."[18]

— Lucy Carroll (1983)

The Law

editLord Dalhousie personally finalised the bill despite the opposition and it being considered a flagrant breach of customs as prevalent then.[19][20] Thus, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar changed the fate of Hindu widows across India, which was essential in reforming Hinduism that was submerged in social evils during 19th century.[21]

The preamble and sections 1, 2, and 5 of the Law:[10]

Whereas it is known that, by the law as administered in the Civil Courts established in the territories in the possession and under the Government of the East India Company, Hindu widows with certain exceptions are held to be, by reason of their having been once married, incapable of contracting a second valid marriage, and the offsprings of such widows by any second marriage are held to be illegitimate and incapable of inheriting property; and

Whereas many Hindus believe that this imputed legal incapacity, although it is in accordance with established custom, is not in accordance with a true interpretation of the precepts of their religion, and desire that the civil law administered by the Courts of Justice shall no longer prevent those Hindus who may he so minded from adopting a different custom, in accordance with the dictates of their own conscience, and

Where it is just to relieve all such Hindus from this legal incapacity of which they complain, and the removal of all legal obstacles to the marriage of Hindu widows will tend to the promotion of good morals and to the public welfare;

It is enacted as follows:

- No marriage contracted between Hindus shall be invalid, and the issue of no such marriage shall be illegitimate, by reason of the woman having been previously married or betrothed to another person who was dead at the time of such marriage, any custom and any interpretation of Hindu Law to the contrary notwithstanding.

- All rights and interests which any widow may have in her deceased husband's property by way of maintenance, or by inheritance to her husband or to his lineal successors, or by virtue of any will or testamentary disposition conferring upon her, without express permission to remarry, only a limited interest in such property, with no power of alienating the same, shall upon her re-marriage cease and determine as if she had then died; and the next heirs of her deceased husband or other persons entitled to the property on her death, shall thereupon succeed to the same ....

- Except as in the three preceding sections is provided, a widow shall not by reason of her re-marriage forfeit any property or any right to which she would otherwise be entitled, and every widow who has re-married shall have the same rights of inheritance as she would have had, had such marriage been her first marriage.

Repeal in 1983

editThe widow remarriage act got repealed in 1983 and six years later Hindu Widows Remarriage and Property act, 1989.

Notes

edit- ^ a b Carroll 2008, p. 78

- ^ Chandrakala Anandrao Hate (1948). Woman and Her Future. New Book Company. p. 156. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Penelope Carson (2012). The East India Company and Religion, 1698-1858. Boydell Press. pp. 225–. ISBN 978-1-84383-732-9.

- ^ B. R. Sunthankar (1988). Nineteenth Century History of Maharashtra: 1818-1857. Shubhada-Saraswat Prakashan. p. 522. ISBN 978-81-85239-50-7. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Mohammad Tarique. Modern Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-07-066030-4. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ John F. Riddick (2006). The History of British India: A Chronology. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-313-32280-8. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Indrani Sen (2002). Woman and Empire: Representations in the Writings of British India, 1858-1900. Orient Blackswan. pp. 124–. ISBN 978-81-250-2111-7.

- ^ a b Peers 2006, pp. 52–53

- ^ Forbes 1999, p. 23

- ^ a b Carroll 2008, p. 80

- ^ Iswar Chandra was supported in this by many wise and elite gentlemen of the society and the first signatory on his application to the then Governor General was Shri Kasinath Dutta, belonging to the Hatkhola Dutta lineage,Chakraborty 2003, p. 125

- ^ H. R. Ghosal (1957). "THE REVOLUTION BEHIND THE REVOLT (A comparative study of the causes of the 1857 uprising)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 20: 293–305. JSTOR 44304480.

- ^ Pratima Asthana (1974). Women's Movement in India. Vikas Publishing House. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7069-0333-1. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Subal Chandra Mitra (1902). Isvar Chandra Vidyasagar. Sarat Chandra Mitra, New Bengal Press. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Kandukuri Veeresalingam (1907). Śrī Parāśara smṛtiḥ (in Telugu). Chennapuri: Sri Chintamani Mudraksharasala. p. 22.

- ^ Guru Prasad Sharma (1998). Parāśara smṛtiḥ (in Hindi). Varanasi: Chowkhamba Vidyabhavan. p. 31.

- ^ Ishvarchandra Vidyasagar (translated by Brian A. Hatcher) (2012). Hindu Widow Marriage. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231526609.

- ^ Carroll 2008, p. 79

- ^ Amit Kumar Gupta (5 October 2015). Nineteenth-Century Colonialism and the Great Indian Revolt. Taylor & Francis. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-317-38668-1. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Belkacem Belmekki (2008). "A Wind of Change: The New British Colonial Policy in Post-Revolt India". AEDEAN: Asociación Española de Estudios Anglo-americanos. 2 (2): 111–124. JSTOR 41055330.

- ^ Grin, ed. (26 September 2020). "How Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar used an ancient Hindu text to make widow remarriage legal in the 19th century". Medium. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

References

edit- Carroll, Lucy (2008). "Law, Custom, and Statutory Social Reform: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856". In Sumit Sarkar; Tanika Sarkar (eds.). Women and social reform in modern India: a reader. Indiana University Press. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-253-22049-3. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Chakraborty, Uma (2003). Gendering caste through a feminist lens. Popular Prakashan. p. 125. ISBN 978-81-85604-54-1. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Forbes, Geraldine (1999). Women in modern India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-521-65377-0. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Peers, Douglas M. (2006). India under colonial rule: 1700-1885. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3. Retrieved 8 November 2018.