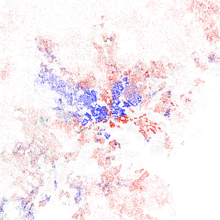

The history of White Americans in Baltimore dates back to the 17th century when the first white European colonists came to what is now Maryland and established the Province of Maryland on what was then Native American land. White Americans in Baltimore are Baltimoreans "having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East or North Africa."[1][2] Majority white for most of its history, Baltimore no longer had a white majority by the 1970s.[3] As of the 2010 census, white Americans are a minority population of Baltimore at 29.6% of the population (Non-Hispanic whites were 28% of the population). White Americans have played a substantial impact on the culture, dialect, ethnic heritage, history, politics, and music of the city. Since the earliest English settlers arrived on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay, Baltimore's white population has been sustained by substantial immigration from all over Europe, particularly Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Southern Europe, as well as a large out-migration of White Southerners from Appalachia. Numerous white immigrants from Europe and the European diaspora have immigrated to Baltimore from the United Kingdom, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Italy, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Lithuania, Russia, Ukraine, Spain, France, Canada, and other countries, particularly during the late 19th century and early 20th century. Smaller numbers of white people have immigrated from Latin America, the Caribbean (particularly Haiti), the Middle East, North Africa, and other non-European regions. Baltimore also has a prominent population of white Jews of European descent, mostly with roots in Central and Eastern Europe. There is a smaller population of white Middle Easterners and white North Africans, most of whom are Arab, Persian, Israeli, or Turkish. The distribution of White Americans in Central and Southeast Baltimore is sometimes called "The White L", while the distribution of African Americans in East and West Baltimore is called "The Black Butterfly."[4]

Demographics

edit| White population in Baltimore | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Percentage | |

| 1790 | 88.3% | |

| 1800 | 78.8% | |

| 1810 | 77.8% | |

| 1820 | 76.6% | |

| 1830 | 76.5% | |

| 1840 | 79.3% | |

| 1850 | 83.2% | |

| 1860 | 86.9% | |

| 1870 | 85.2% | |

| 1880 | 83.8% | |

| 1890 | 84.5% | |

| 1900 | 84.3% | |

| 1910 | 84.8% | |

| 1920 | 85.2% | |

| 1930 | 82.3% | |

| 1940 | 80.6% | |

| 1950 | 76.2% | |

| 1960 | 65% | |

| 1970 | 53% | |

| 1980 | 43.9% | |

| 1990 | 39.1% | |

| 2000 | 31% | |

| 2010 | 29.6% | |

In the 1790 census, the first census in the history of the United States, white Americans constituted 88.3% of Baltimore's population. 11,925 lived in Baltimore in that year.[5]

In 1815, 36,000 white people lived in Baltimore. By 1829, Baltimore was home to 61,000 white people.[6]

From 1800 until 1840, white Americans were around 77–79% of Baltimore's population. The white population began to increase in the mid and late 1800s, boosted by large-scale European immigration, resulting in Baltimore's whites remaining between 80% and 87% of the population between the 1850s and the 1920s.[5]

During the time of the Hillbilly Highway, between 1910 and 1970, thousands of white people from Appalachia and the Southern states moved to Baltimore in search of better socioeconomic conditions. Baltimore was a major destination for these white Southern and Appalachian economic migrants.[citation needed]

In the 1960 United States census, Baltimore was home to 610,608 white residents, 65% of Baltimore's population.[7] By 1970 white Americans were 53% of Baltimore's population, on the verge of becoming the minority for the first time due white flight to the suburbs and an increasing African-American population.[5]

In the 1980 United States census, there were 345,113 white people living in Baltimore, constituting 43.9% of the population. The 1980 census was the first census for which white people were a minority in Baltimore.[8] By the 1990 United States census, there were 287,753 white Americans, constituting 39.1% of the population.[8]

In the 2010 United States census, 29.6% of the population of Baltimore was white, a total population of 183,830 people.[9]

In 2018, 30.3% of Baltimore was white and 27.6% was non-Hispanic white.[10]

Baltimore's white population has been increasing in numbers since the 2010s. This is largely due to gentrification and an influx of white millennials.[11]

History

editPre-history and early white European exploration

editIn the early 1600s, the immediate Baltimore vicinity was populated by Native Americans who had lived there since at least the 10th millennium BC, when Paleo-Indians first settled in the region.[12] During the Late Woodland period, the archaeological culture known as the "Potomac Creek complex" resided in an area from Baltimore to the Rappahannock River in Virginia, primarily along the Potomac River downstream from the Fall Line.[13] The Baltimore County area northward was used as hunting grounds by the Susquehannocks living in the lower Susquehanna River valley who "controlled all of the upper tributaries of the Chesapeake" but "refrained from much contact with Powhatan in the Potomac region."[14] Pressured by the Susquehannocks, the Piscataway tribe of Algonquians stayed well south of the Baltimore area and inhabited primarily the north bank of the Potomac River in what is now Charles and southern Prince George's south of the Fall Line[15][16][17] as depicted on John Smith's 1608 map which faithfully mapped settlements, mapped none in the Baltimore vicinity, while noting a dozen Patuxent River settlements that were under some degree of Piscataway suzerainty.

In 1608, Captain John Smith traveled 210 miles from Jamestown to the uppermost Chesapeake Bay, leading the first European expedition to the Patapsco River, a word used by the Algonquin language natives who fished shellfish and hunted[18] The name "Patapsco" is derived from pota-psk-ut, which translates to "backwater" or "tide covered with froth" in Algonquian dialect.[19] A quarter-century after John Smith's voyage, English colonists began to settle in Maryland. The English were initially frightened by the Piscataway in southern Maryland because of their body paint and war regalia, even though they were a peaceful tribe. The chief of the Piscataway tribe was quick to grant the English permission to settle within Piscataway territory and cordial relations were established between the English and the Piscataway.[20]

17th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

18th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

19th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

20th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

During the civil rights movement between the 1930s and the 1960s, many white Americans in Baltimore reacted violently to African-Americans and were intransigent in their support for segregation. Some white residents of Baltimore engaged in acts of terrorism against African-Americans, including the 1911 lynching of King Johnson in the neighborhood of Brooklyn.[21] White elected officials and citizens made life difficult for African-Americans by engaging in various forms of discrimination. However, some anti-racist white liberals and progressives joined with African-American activists. White Communists were among the most vocal white supporters of the civil rights movement.[22]

The largely white Baltimore Committee for Political Freedom was created due to fears that Baltimore police were planning to assassinate Black Panther Party leaders in Baltimore, with Reverend Chester Wickwire and the sociologist Peter H. Rossi playing a prominent role.[23]

21st century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

Due to demographic and socioeconomic changes, Baltimore's urban core is slowly becoming more white and more affluent. Young urban professionals have been attracted to the city, echoing patterns of gentrification that have occurred across many major American cities in recent decades. As the city's white population has increased and the rate of poverty has dropped, income and property values have been rising. The effects of gentrification and a growing white population have been felt the most in the historically black working-class neighborhoods of East Baltimore and to a lesser extent in the neighborhoods of North Central Baltimore. The proximity of these neighborhoods to the Johns Hopkins Hospital has been a major factor in the gentrification and increasing white population of East Baltimore's neighborhoods.[24] Because of these demographic changes, Baltimore has been called "the new Brooklyn" and has been compared to similarly gentrifying cities across the United States such as New York City and Washington, D.C.[25]

Culture

editDialect

editAccording to linguists, the "hon" accent that is popularized in the media as being spoken by Baltimoreans is particular to Baltimore's white working-class.[26] White working-class families who migrated out of Baltimore city into Baltimore County and Carroll County along the Maryland Route 140 and Maryland Route 26 corridors brought local pronunciations with them, creating colloquialisms that make up the Baltimore accent, cementing the image of "Bawlmerese" as the "Baltimore accent". This white working-class dialect is not the only "Baltimore accent", as Black Baltimoreans have their own unique accent. For example, among Black speakers, Baltimore is pronounced more like "Baldamore," as compared to "Bawlmer" among white speakers.[27]

Literature

editIn 2003, Kenneth D. Durr published Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980, an historical examination of white working-class life and politics in Baltimore during the mid to late 1900s.[28]

Religion

editMost White Americans in Baltimore are Christians, generally either Catholic or Protestant. Smaller numbers of white Christians belong to denominations such as Mormonism, the Jehovah's Witnesses, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Oriental Orthodoxy. Minorities of White Americans belong to other religions such as Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam, while some are atheist or agnostic.[citation needed]

Christianity

editDuring the 1800s and 1900s, many neighborhoods of Baltimore were reserved exclusively for white Christians. One such neighborhood, Roland Park, was developed as a wealthy white Christian enclave for "discriminating" people that used racially restrictive covenants to exclude African-Americans. Some white Christian neighborhoods used restrictive covenants to exclude Jewish Americans as well. At that time, living in a white Christian neighborhood was a sign of social status.[29]

During this same time period, white Protestant-dominated banks would ignore or turn away customers who were Eastern European or Southern European immigrants; consequently "white ethnic" immigrants would establish their own banking institutions to serve the specific needs of their communities. These banks for white ethnic immigrants had hours and customs that seemed less alien to immigrants and often had translators on staff. Discrimination against non-WASP immigrants persisted in banking until the 1930s.[30] As late as the 1930s and 1940s it was not uncommon for Slavic Catholics, such as Poles and Czechs, to be called ethnic and religious slurs such as "bohunks" and "fish eaters." Slavs were often stereotyped as stupid and superstitious. White Protestants coined the term "fish eater" to refer to Catholic immigrants because the Catholics did not eat meat on Fridays.[31]

Baltimore, like many other major northeastern cities, has a large population of white Catholics, many of whom are "white ethnic" immigrants and descendants of immigrants from majority-Catholic countries of Europe such as Ireland, Italy, Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Historically, the Catholic Church in Baltimore practiced segregation of its white and black worshippers. In the early 21st century, Roman Catholic authorities began to acknowledge the long legacy of racism from the majority-white leadership of the Church. The first Archbishop of Baltimore, John Carroll, was a white slave-owner. Many white Catholics in Baltimore moved to the suburbs during the period of white flight between the 1960s and 1980s, leaving most Roman Catholic churches in the city with an African-American majority while many Roman Catholic churches in the suburbs are majority white.[32]

Judaism

editA large minority of white Baltimoreans have been Jewish, predominantly Ashkenazi Jews of European descent. Between the 1880s and the 1920s, Baltimore received tens of thousands of white Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants arriving from Central and Eastern Europe.[33] Due to the largely European origins of Baltimore's Jewish community, close to 90% of Baltimore area Jews are white. However, as of 2010, around 8% of Jewish households in the Greater Baltimore area were multiracial.[34] Following the 1968 riots and the subsequent white flight, many white Jews in the city (along with many white gentiles), left the city for the suburbs. Today, thousands of descendants of these white Jews live in Baltimore County, especially in Pikesville and Owings Mills, though many remain in the city in neighborhoods such as Park Heights, Mount Washington, and Roland Park. Historically, there were strong links between African-American and Jewish-American communities in Baltimore and many white Jewish Baltimoreans were strong supporters of the civil rights movement. However, there has been tension between the two communities, with instances of anti-black racism from white Jews such as the 2010 Park Heights beating of a black teenager by white members of an Orthodox Jewish community patrol group.[35] White Jews in Baltimore have experienced a mixture of both religious and racial antisemitism as well as privilege due to their white skin. In majority-white Jewish spaces in Baltimore, white Jews are sometimes accepted while black Jews and other Jews of color may face skepticism and questioning of their identity.[36]

Islam

editThere are a small number of white Muslims in Baltimore, most of whom are converts. Some white Muslims have earned leadership positions within their communities, with a few becoming teachers at children's schools for their local mosques.[37]

Majority white neighborhoods in Baltimore

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2019) |

See also

edit- Ethnic groups in Baltimore

- White Hispanic and Latino Americans

- History of Baltimore

- History of the Hispanics and Latinos in Baltimore

- History of the Jews in Baltimore

- Non-Hispanic whites

- Old Stock Americans

- White Americans in Maryland

- White flight

- History of the Irish in Baltimore

- History of Czechs in Baltimore

- History of Poles in Baltimore

- History of the French in Baltimore

- History of Lithuanians in Baltimore

- History of Russians in Baltimore

- History of Ukrainians in Baltimore

- History of Italians in Baltimore

- History of Greeks in Baltimore

- History of the Germans in Baltimore

- History of Syrians in Baltimore

- History of the Appalachian people in Baltimore

References

edit- ^ "B03002 Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race - United States - 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2017. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: UNITED STATES". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Alabaster cities: urban U.S. since 1950. John R. Short (2006). Syracuse University Press. p.142. ISBN 0-8156-3105-7

- ^ "Two Baltimores: The White L vs. the Black Butterfly". Baltimore City Paper. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ a b c "Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United States" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Mount Vernon Place – Stories of Slavery & Emancipation". Baltimore Heritage. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Census Tracts Baltimore, Md" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ a b "Census 1980, 1990 and 2000 Profile of General Demographic Characteristics (PDF Format)" (PDF). Maryland Department of Planning, Maryland State Data Center. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin: 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". American FactFinder. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Baltimore's Demographic Divide". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Akerson, Louise A. (1988). American Indians in the Baltimore area. Baltimore, Maryland: Baltimore Center for Urban Archaeology (Md.). p. 15. OCLC 18473413.

- ^ Potter, Stephen R. (1993). Commoners, Tribute, and Chiefs: The Development of Algonquian Culture in the Potomac Valley. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-8139-1422-1. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Youssi, Adam (2006). "The Susquehannocks' Prosperity & Early European Contact". Historical Society of Baltimore County. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Alex J. Flick; et al. (2012). "A Place Now Known Unto Them: The Search for Zekiah Fort" (PDF). St. Mary's College of Maryland. p. 11. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ^ Murphree, Daniel Scott (2012). Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 489, 494. ISBN 978-0-313-38126-3. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ As depicted on a map of the Piscataway lands in Kenneth Bryson, Images of America: Accokeek (Arcadia Publishing, 2013) pp. 10-11, derived from Alice and Henry Ferguson, The Piscataway Indians of Southern Maryland (Alice Ferguson Foundation, 1960) pp. 8 (map) and p. 11: "By the beginning of Maryland (English) settlement, pressure from the Susquehannocks had reduced...the Piscataway 'empire'...to a belt bordering the Potomac south of the falls and extending up the principle tributaries. Roughly, the 'empire' covered the southern half of present Prince Georges County and all, or nearly all, of Charles County."

- ^ A Point of Natural Origin Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine and Locust Point – Celebrating 300 Years of a Historic Community Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, Scott Sheads, Mylocustpoint.

- ^ "Ghosts of industrial heyday still haunt Baltimore's harbor, creeks". Chesapeake Bay Journal. Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ Murphree, Daniel Scott (2012). Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-313-38126-3. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Negro Lynched". Baltimore Sun. 26 December 1911. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Baltimore Civil Rights Heritage 1930-1965". Baltimore's Civil Rights Heritage. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "1966–1976: After the Unrest". Baltimore Heritage. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Maryland Demographic Assessment" (PDF). The Mid-Atlantic Association of Community Health Centers (MACHC). Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Baltimore's white population swells with millennials, resembling D.C., Brooklyn". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ "The Relevatory Power of Language". Maryland Humanities Council. May 11, 2019.

- ^ DeShields, Inte'a. "Baldamor, Curry, and Dug': Language Variation, Culture, and Identity among African American Baltimoreans". Podcast. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Heineman on Durr, 'Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980'". Humanities and Social Sciences Online. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Jewish congregation begins new chapter in Roland Park". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Scarborough, Melanie (2007). "Establishing Roots in the Community". Community Banker. Washington, D.C.: America's Community Bankers. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "OBSERVER; Prejudices Without The Mask". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Baltimore Church Faces Its History of Racism". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Baltimore". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "2010 Baltimore Jewish Community Study". 2010 Baltimore Jewish Community Study. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "The story behind Baltimore's Jews and their African-American ties". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "In face of doubters, Black rabbi finds his spiritual destiny Faith is Proof Enough". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ Bowen, Patrick D. (2015). A history of conversion to Islam in the United States. Volume 1, White American Muslims before 1975. Leiden; Boston: Brill. pp. 336–337. ISBN 9789004299948.

- ^ "Armistead Gardens Ready to Experiment". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "The tale of two Targets, a Baltimore segregation story". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

Further reading

edit- Durr, Kenneth D. Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980, The University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Pietila, Antero. Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City, Ivan R. Dee, 2010.