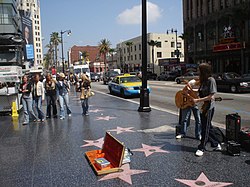

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a landmark which consists of 2,800[1] five-pointed terrazzo-and-brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in the Hollywood district of Los Angeles. The stars, the first of which were permanently installed in 1960, are monuments to achievement in the entertainment industry, bearing the names of a mix of actors, musicians, producers, directors, theatrical/musical groups, fictional characters, and others.

| |

| |

Location of the Hollywood Walk of Fame in Hollywood | |

| Established | February 8, 1960 |

|---|---|

| Location | Hollywood Blvd. and Vine St., Hollywood, Los Angeles |

| Coordinates | 34°06′06″N 118°19′36″W / 34.1016°N 118.3267°W |

| Type | Entertainment hall of fame |

| Visitors | 10 million annually |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | walkoffame |

| Designated | July 5, 1978 |

| Reference no. | 194 |

The Walk of Fame is administered by the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, who hold a trademark right to the combined star & movie camera symbol only, and maintained by the self-financing Hollywood Historic Trust. The Hollywood Chamber collects fees from celebrities (or their sponsors) that wish to have a star (currently $75K)[2] which pays for the creation and installation of the star, as well as maintenance of the Walk of Fame. The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce does not own trademark rights to the star with other symbols (i.e. television, microphone, record disc), so those symbols are free to use for commercial purposes.[3] It is a popular tourist attraction, receiving an estimated 10 million annual visitors in 2010.[4][5]

Description

editThe Walk of Fame runs 1.3 miles (2.1 km) from east to west on Hollywood Boulevard, from Gower Street to the Hollywood and La Brea Gateway at La Brea Avenue in addition to a short segment on Marshfield Way that runs diagonally between Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea; and 0.4 miles (0.64 km) north to south on Vine Street between Yucca Street and Sunset Boulevard. According to a 2003 report by the market research firm NPO Plog Research, the Walk attracts about 10 million visitors annually—more than the Sunset Strip, the TCL Chinese Theatre (formerly Grauman's), the Queen Mary, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art combined—and has played an important role in making tourism the largest industry in Los Angeles County.[4]

Categorization

editAs of 2023[update], the Walk of Fame consists of 2,752 stars,[1] which are spaced at 6-foot (1.8 m) intervals. The monuments are coral-pink terrazzo five-point stars rimmed with brass[6] (not bronze, an oft-repeated inaccuracy)[citation needed] inlaid into a charcoal-colored terrazzo background. The name of the honoree is inlaid in brass block letters in the upper portion of each star. Below the inscription, in the lower half of the star field, a round inlaid brass emblem indicates the category within the entertainment industry of the honoree's contributions. There are six fixed categories and honorees must fit into one of them.[6] The six categories and their emblems are:

- Classic film camera representing motion pictures.

- Television receiver representing broadcast television.

- Phonograph record representing audio recording or music.

- Radio microphone representing broadcast radio.

- Comedy/tragedy masks representing theater/live performance (added in 1984).

- [image needed] Athletic trophy representing sports entertainment (added in 2023).

Of the stars on the Walk to date, 47% have been awarded in the motion pictures category, 24% in television, 17% in audio recording or music, 10% in radio, fewer than 2% in theater/live performance, and fewer than 1% in sports entertainment. According to the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, approximately 30 new stars are added to the Walk each year.[6]

Star locations

editLocations of individual stars are not necessarily arbitrary. Stars of many particularly well-known celebrities are found in front of the TCL (formerly Grauman's) Chinese Theatre. Oscar-winners' stars are usually placed near the Dolby Theatre,[citation needed] site of the annual Academy Awards presentations. Locations are occasionally chosen for ironic or humorous reasons: Mike Myers's star lies in front of an adult store called the International Love Boutique,[7] an association with his Austin Powers roles; Roger Moore's star and Daniel Craig's star are located at 7007 Hollywood Boulevard in recognition of their titular role in the James Bond 007 film series;[8] Ed O'Neill's star is located outside a shoe store in reference to his character's occupation on the TV show Married ... with Children;[9] and The Dead End Kids' star is located at the corner of LaBrea and Hollywood Boulevard.[further explanation needed][10]

Honorees may request a specific location for their star, although final decisions remain with the Chamber.[11] Jay Leno, for example, requested a spot near the corner of Hollywood Blvd. and Highland Ave. because he was twice picked up at that location by police for vagrancy (though never actually charged) shortly after his arrival in Hollywood.[12] George Carlin chose to have his star placed in front of the KDAY radio station near the corner of Sunset Blvd. and Vine St., where he first gained national recognition.[13] Lin-Manuel Miranda chose a site in front of the Pantages Theatre where his musicals, In The Heights and Hamilton, played.[14] Carol Burnett explained her choice in her 1986 memoir: While working as an usherette at the historic Warner Brothers Theatre (now the Hollywood Pacific Theatre) during the 1951 run of Alfred Hitchcock's film Strangers on a Train, she took it upon herself to advise a couple arriving during the final few minutes of a showing to wait for the next showing, to avoid seeing (and spoiling) the ending. The theater manager fired her on the spot for "insubordination" and humiliated her by stripping the epaulets from her uniform in the theater lobby. Twenty-six years later, at her request, Burnett's star was placed at the corner of Hollywood and Wilcox—in front of the theater.[15]

Alternative star designs

editSpecial category stars recognize various contributions by corporate entities, service organizations, and special honorees, and display emblems unique to those honorees.[16] For example, former Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley's star displays the seal of the city of Los Angeles;[17][18] the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) star emblem is a replica of a Hollywood Division badge;[19] and stars representing corporations, such as Victoria's Secret and the Los Angeles Dodgers, display the honoree's corporate logo.[16][20] The "Friends of the Walk of Fame" monuments are charcoal terrazzo squares rimmed by miniature pink terrazzo stars displaying the then five standard category emblems,[21] along with the sponsor's corporate logo, with the sponsor's name and contribution in inlaid brass block lettering.[22][23] Special stars and Friends monuments are granted by the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce or the Hollywood Historic Trust, but are not part of the Walk of Fame proper and are located nearby on private property.[22][24]

The monuments for the Apollo 11 mission to the Moon are uniquely shaped: Four identical circular moons, each bearing the names of the three astronauts (Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., and Michael Collins), the date of the first Moon landing ("7/20/69"), and the words "Apollo XI", are set on the four corners of the intersection of Hollywood and Vine.[25]

History

editOrigin

editThe Hollywood Chamber of Commerce credits E.M. Stuart, its volunteer president in 1953, with the original idea for creating a Walk of Fame. Stuart reportedly proposed the Walk as a means to "maintain the glory of a community whose name means glamour and excitement in the four corners of the world".[26] Harry Sugarman, another Chamber member and president of the Hollywood Improvement Association, received credit in an independent account.[27] A committee was formed to flesh out the idea, and an architectural firm was retained to develop specific proposals. By 1955, the basic concept and general design had been agreed upon, and plans were submitted to the Los Angeles City Council.[28][29][30]

Multiple accounts exist for the origin of the star concept. According to one, the historic Hollywood Hotel, which stood for more than 50 years on Hollywood Boulevard at the site now occupied by the Ovation Hollywood complex and the Dolby (formerly Kodak) Theatre[31]—displayed stars on its dining room ceiling above the tables favored by its most famous celebrity patrons, and that may have served as an early inspiration.[28] By another account, the stars were "inspired ... by Sugarman's Tropics Restaurant drinks menu, which featured celebrity photos framed in gold stars".[27][32]

In February 1956, a prototype was unveiled featuring a caricature of an example honoree (John Wayne, by some accounts[33]) inside a blue star on a brown background.[26] However, caricatures proved too expensive and difficult to execute in brass with the technology available at the time; and the brown and blue motif was vetoed by Charles E. Toberman, the legendary real estate developer known as "Mr. Hollywood", because the colors clashed with a new building he was erecting on Hollywood Boulevard.[26][34]

Selection and construction

editBy March 1956, the final design and coral-and-charcoal color scheme had been approved. Between the spring of 1956 and the fall of 1957, 1,558 honorees were selected by committees representing the four major branches of the entertainment industry at that time: motion pictures, television, audio recording, and radio. The committees met at the Brown Derby restaurant,[35] and they included such prominent names as Cecil B. DeMille, Samuel Goldwyn, Jesse L. Lasky, Walt Disney, Hal Roach, Mack Sennett, and Walter Lantz.[26]

A requirement stipulated by the original audio recording committee (and later rescinded) specified minimum sales of one million records or 250,000 albums for all music category nominees. The committee soon realized that many important recording artists would be excluded from the Walk by that requirement. As a result, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences was formed to create a separate award for the music industry, leading to the first Grammy Awards in 1959.[36]

Construction of the Walk began in 1958, but two lawsuits delayed completion. The first lawsuit was filed by local property owners challenging the legality of the $1.25 million tax assessment (equivalent to $13 million in 2023) levied upon them to pay for the Walk, along with new street lighting and trees. In October 1959, the assessment was ruled legal.[26] The second lawsuit, filed by Charles Chaplin Jr., sought damages for the exclusion of his father, whose nomination had been withdrawn due to pressure from multiple quarters. Chaplin's suit was dismissed in 1960, paving the way for completion of the project.[26][37][38]

While Joanne Woodward is often singled out as the first person to receive a star on the Walk of Fame—possibly because she was the first to be photographed with it[11]—the original stars were installed as a continuous project, with no individual ceremonies. Woodward's name was one of eight drawn at random from the original 1,558 and inscribed on eight prototype stars that were built while litigation was holding up permanent construction.[39][40][41] The eight prototypes were installed temporarily on the northwest corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Avenue in August 1958 to generate publicity and to demonstrate how the Walk would eventually look.[26] The other seven names were Olive Borden, Ronald Colman, Louise Fazenda, Preston Foster, Burt Lancaster, Edward Sedgwick, and Ernest Torrence.[26][42] Official groundbreaking took place on February 8, 1960.[28] On March 28, 1960, the first permanent star, director Stanley Kramer's, was completed on the easternmost end of the new Walk near the intersection of Hollywood and Gower.[26][43]

Stagnation and revitalization

editAlthough the Walk was originally conceived in part to encourage redevelopment of Hollywood Boulevard, the 1960s and 1970s were periods of protracted urban decay in the Hollywood area as residents moved to nearby suburbs.[44][45] After the initial installation of approximately 1,500 stars in 1960 and 1961, eight years passed without the addition of a new star. In 1962, the Los Angeles City Council passed an ordinance naming the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce "the agent to advise the City" about adding names to the Walk, and the Chamber, over the following six years, devised rules, procedures, and financing methods to do so.[26] In December 1968, Richard D. Zanuck was awarded the first star in eight years in a presentation ceremony hosted by Danny Thomas.[26][35][46] In July 1978, the city of Los Angeles designated the Hollywood Walk of Fame a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument.[47]

Radio personality, television producer, and Chamber member Johnny Grant is generally credited with implementing the changes that resuscitated the Walk and established it as a significant tourist attraction.[35][48] Beginning in 1968, Grant stimulated publicity and encouraged international press coverage by requiring that each recipient personally attend his or her star's unveiling ceremony.[35] Grant later recalled that "it was tough to get people to come accept a star" until the neighborhood finally began its recovery in the 1980s.[45]

In 1980, Grant instituted a fee of $2,500 (equivalent to $9,245 in 2023), payable by the person or entity nominating the recipient, to fund the Walk of Fame's upkeep and minimize further taxpayer burden.[35] The fee has increased incrementally over time. By 2002, it had reached $15,000 (equivalent to $25,410 in 2023),[49] and stood at $30,000 in 2012 (equivalent to $39,814 in 2023).[6] As of 2023[update], the fee was $75,000, about eight times the original amount adjusted for inflation.[50]

Grant was himself awarded a star in 1980 for his television work.[26] In 2002, he received a second star in the "special" category to acknowledge his pivotal role in improving and popularizing the Walk.[51] He was also named chairman of the Selection Committee and Honorary Mayor of Hollywood (a ceremonial position previously held by Art Linkletter and Monty Hall,[52][53] among others).[26][51] He remained in both offices from 1980 until his death in 2008 and hosted the great majority of unveiling ceremonies during that period. His unique special-category star, with its emblem depicting a stylized "Great Seal of the City of Hollywood",[54] is located at the entrance to the Dolby Theatre adjacent to Johnny Grant Way.[55][56]

Expansion

editIn 1984, a fifth category, Live Theatre, was added to acknowledge contributions from the live performance branch of the entertainment industry, and a second row of stars was created on each sidewalk to alternate with the existing stars.[26]

In 1994, the Walk of Fame was extended one block to the west on Hollywood Boulevard, from Sycamore Avenue to North LaBrea Avenue (plus the short segment of Marshfield Way that connects Hollywood and La Brea), where it now ends at the silver "Four Ladies of Hollywood" gazebo and the special "Walk of Fame" star.[57] At the same time, Sophia Loren was honored with the 2,000th star on the Walk.[26]

During construction of tunnels for the Los Angeles subway system in 1996, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) removed and stored more than 300 stars.[58] Controversy arose when the MTA proposed a money-saving measure of jackhammering the 3-by-3-foot terrazzo pads, preserving only the brass lettering, surrounds, and medallions, then pouring new terrazzo after the tunnels were completed;[59] but the Cultural Heritage Commission ruled that the star pads were to be removed intact.[60]

In 2023, a sixth category, Sports Entertainment, was added to acknowledge contributions of athletes to the entertainment industry.[61]

Restoration

editIn 2008, a long-term restoration project began with an evaluation of all 2,365 stars on the Walk at the time, each receiving a letter grade of A, B, C, D, or F. Honorees whose stars received F grades, indicating the most severe damage, were Joan Collins, Peter Frampton, Dick Van Patten, Paul Douglas, Andrew L. Stone, Willard Waterman, Richard Boleslavsky, Ellen Drew, Frank Crumit, and Bobby Sherwood. Fifty celebrities' stars received "D" grades. The damage ranged from minor cosmetic flaws caused by normal weathering to holes and fissures severe enough to constitute a walking hazard. Plans were made to repair or replace at least 778 stars at an estimated cost of over $4 million.[62]

The restoration is a collaboration among the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce and various Los Angeles city and county governmental offices, along with the MTA, which operates the Metro B Line that runs beneath the Walk, since earth movement due to the presence of the subway line is thought to be partly responsible for the damage.[63]

To encourage supplemental funding for the project by corporate sponsors, the "Friends of Walk of Fame" program was inaugurated,[62] with donors recognized through honorary plaques adjacent to the Walk of Fame in front of the Dolby Theatre.[22] The program has received some criticism; Alana Semuels of the Los Angeles Times described it as "just the latest corporate attempt to buy some good buzz", and quoted a brand strategist who said, "I think Johnny Grant would roll over in his grave".[22]

Los Angeles introduced the "Heart of Hollywood Master Plan", which promotes the idea of closing Hollywood Boulevard to traffic and creating a pedestrian zone from La Brea Avenue to Highland Avenue, citing an increase in pedestrian traffic including tourism, weekly movie premieres[64] and award shows closures, including ten days for the Academy Award ceremony at the Dolby Theatre.[65][66] In June 2019, the city of Los Angeles commissioned Gensler Architects to provide a master plan for a $4 million renovation to improve and "update the streetscape concept" for the Walk of Fame.[67][68][69] Los Angeles city councilmember Mitch O'Farrell released the draft master plan designed by Gensler and Studio-MLA in January 2020. It proposed widening the sidewalks, adding bike lanes, new landscaping, sidewalk dining, removing lanes of car traffic and street parking between the Pantages Theater (Gower Street) at the east and The Emerson Theatre (La Brea Avenue) at the west end of the boulevard.[70] The approved phase one includes removing the parking lanes between Orange Drive and Gower Street, adding street furnishings with benches, tables and chairs with sidewalk widening. Phase two is in the schematic stage. Phase two is planned for 2024 and will include closing down the boulevard to two lanes, adding landscaping with shade trees and five public plazas made up of art deco designed street pavers and kiosks.[71][72] Planned to be completed by 2026, funding is being raised for the $50 million project.[73][74]

Nomination process

editEach year an average of 200 nominations are submitted to the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce Walk of Fame selection committee. Anyone, including fans, can nominate anyone active in the field of entertainment as long as the nominee or their management approves the nomination. Nominees must have a minimum of five years' experience in the category for which they are nominated and a history of "charitable contributions".[75] Posthumous nominees must have been deceased at least five years. At a meeting each June, the committee selects approximately 20 to 24 celebrities to receive stars on the Walk of Fame. One posthumous award is given each year as well. The nominations of those not selected are rolled over to the following year for reconsideration; those not selected two years in a row are dropped, and must be renominated to receive further consideration. Living recipients must agree to personally attend a presentation ceremony within two years of selection. If the ceremony is not scheduled within two years, a new application must be submitted. A relative of deceased recipients must attend posthumous presentations. Presentation ceremonies are open to the public.[6]

A fee of $75,000 (as of 2023[update]),[50] payable at time of selection, is collected to pay for the creation and installation of the star, as well as general maintenance of the Walk of Fame. The fee is usually paid by the nominating organization, which may be a film studio, record company, broadcaster, or other sponsor involved with the prospective honoree.[35][76] The Starz cable network, for example, paid for Dennis Hopper's star as part of the promotion for its series Crash.[35][77]

Traditionally, the identities of selection committee members, other than its chairman, have not been made public in order to minimize conflicts of interest and to discourage lobbying by celebrities and their representatives (a significant problem during the original selections in the late 1950s). However, in 1999, in response to intensifying charges of secrecy in the selection process, the Chamber disclosed the members' names: Johnny Grant, the longtime chair and representative of the television category; Earl Lestz, president of Paramount Studio Group (motion pictures); Stan Spero, retired manager with broadcast stations KMPC and KABC (radio); Kate Nelson, owner of the Palace Theatre (live performance); and Mary Lou Dudas, vice president of A&M Records (recording industry).[78] Since that 1999 announcement, the chamber has revealed only that Lestz (who received his own star in 2004) became chairman after Grant died in 2008. Their current official position is that "each of the five categories is represented by someone with expertise in that field".[6]

In 2010, Lestz was replaced as chairman by John Pavlik, former Director of Communications[79] for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. While no public announcement was made to that effect, he was identified as chairman in the Chamber's press release announcing the 2011 star recipients.[80] In 2016, the chair, according to the Chamber's 2016 selection announcement, was film producer Maureen Schultz.[81] In 2023, the selection committee chair was radio personality Ellen K.[82]

Rule adjustments

editWalk of Fame rules prohibit consideration of nominees whose contributions fall outside the six major entertainment categories, but the selection committee has been known to adjust interpretations of its rules to justify a selection. The Walk's four round Moon landing monuments at the corners of Hollywood and Vine, for example, officially recognize the Apollo 11 astronauts for "contributions to the television industry." Johnny Grant acknowledged, in 2005, that classifying the first Moon landing as a television entertainment event was "a bit of a stretch".[11] Magic Johnson was added to the motion picture category based on his ownership of the Magic Johnson Theatre chain, citing as precedent Sid Grauman, builder of Grauman's Chinese Theatre.[11]

Muhammad Ali's star was granted after the committee decided that boxing could be considered a form of "live performance". Its placement on a wall of the Dolby Theatre makes it the only star mounted on a vertical surface, acceding to Ali's request that his name not be walked upon,[75][83] as he shared his name with the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[84][85]

All living honorees have been required since 1968 to personally attend their star's unveiling, and approximately 40 have declined the honor due to this condition.[11] The only recipient to date who failed to appear after agreeing to do so was Barbra Streisand, in 1976. Her star was unveiled anyway, near the intersection of Hollywood and Highland.[86] Streisand did attend when her husband, James Brolin, unveiled his star in 1998 two blocks to the east.[87]

Entertainers on the Walk of Fame

editEntertainers with multiple stars

editThe following notable entertainers have had their contributions in multiple categories recognized with multiple stars.

Six

editnone

Five

editGene Autry is the only honoree that was described to have a star in every category during 1983–2023, when the number of categories was five.[88][89]

Four

editBob Hope, Mickey Rooney, Roy Rogers, and Tony Martin each have stars in four categories; Rooney has three of his own and a fourth with his eighth wife, Jan Chamberlin,[90][91] while Rogers also has three of his own, and a fourth with his band, Sons of the Pioneers.[92][93]

Three

editThirty-three honorees, including Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Jo Stafford, Dean Martin, Dinah Shore, Gale Storm, Danny Kaye, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Jack Benny have stars in three categories.[88]

Two

editOver a dozen have two stars:

- Dolly Parton, for her solo work and part of the trio made up of her, Emmylou Harris and Linda Ronstadt.[94]

- Michael Jackson,[95] as a soloist and as a member of The Jacksons.

- Diana Ross, as a member of The Supremes and for her solo work.

- Smokey Robinson, as a solo artist and as a member of The Miracles.

- John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr as individuals and as members of The Beatles.[96]

- George Eastman is the only honoree with two stars in the same category for the same achievement, the invention of roll film.[97]

- Walt Disney, has stars in two different categories for his work in both film and television;[98] in addition, Mickey Mouse (who was originally voiced by Walt Disney) and Disneyland have stars.[99]

- Kermit the Frog, has an individual star for television and as a member of The Muppets for film.

- Bette Davis, Alfred Hitchcock,[100] Paul Henreid,[101] Jane Wyman, Loretta Young, and Vincent Price all have one star each for film and television.

- Doris Day and Judy Garland both have one star each for film and recording.

- Jean Hersholt and Hattie McDaniel both have one star each for film and radio.

- Arlene Francis[102] and Cass Daley[103] both have one star each for television and radio.

Cher forfeited her opportunity to join this list by declining to schedule the mandatory personal appearance when she was selected in 1983.[104] She did, however, attend the unveiling of the Sonny & Cher star in 1998, as a tribute to her recently deceased ex-husband, Sonny Bono.[105]

Unique and unusual

editSixteen stars are identified with a one-word stage name (e.g., Liberace, Pink, Roseanne, and Slash). Clayton Moore is so inextricably linked with his Lone Ranger character, even though he played other roles during his career, that he is one of only two actors to have his character's name alongside his own on his star. The other is Tommy Riggs, whose star references his Betty Lou character.[106] The largest group of individuals represented by a single star is the estimated 122 adults and 12 children[107] collectively known as the Munchkins, from the landmark 1939 film The Wizard of Oz.

Two pairs of stars share identical names representing different people. There are two Harrison Ford stars, honoring the silent film actor (at 6665 Hollywood Boulevard),[108] and the present-day actor (in front of the Dolby Theatre at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard).[109] Two Michael Jackson stars represent the pop singer (at 6927 Hollywood Boulevard),[110] and the radio personality (at 1597 Vine Street).[111]

The Westmores received the first star honoring contributions in theatrical make-up.[citation needed] Other make-up artists on the walk are Max Factor, John Chambers and Rick Baker. Three stars recognize experts in special effects: Ray Harryhausen, Dennis Muren, and Stan Winston. Only two costume designers have received a star: eight-time Academy Award Winner Edith Head, and the first African-American to win an Oscar for costume design, Ruth E. Carter.

Sidney Sheldon is one of two novelists with a star, which he earned for writing screenplays for such films as The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947) before becoming a novelist.[112] The other is Ray Bradbury, whose books and stories have formed the basis of dozens of movies and television programs over a nearly 60-year period.[113]

Nine inventors have stars on the Walk: George Eastman, inventor of roll film;[114] Thomas Edison, inventor of the first true film projector and holder of numerous patents related to motion-picture technology;[115] Lee de Forest, inventor of the triode vacuum tube, which played an important role in the development of radio and television broadcasts,[116][117] and Phonofilm, which made sound films possible; Herbert Kalmus, inventor of Technicolor; Auguste and Louis Lumière, inventors of important components of the motion picture camera; Mark Serrurier, inventor of the technology used for film editing; Hedy Lamarr, co-inventor of a frequency-hopping radio guidance system that was a precursor to Wi-Fi networks and cellular telephone systems;[118] and Ray Dolby, co-developer of the first video tape recorder and inventor of the Dolby noise-reduction system.

A few star recipients moved on after their entertainment careers to political notability. Two Presidents of the United States, Ronald Reagan (40th President) and Donald Trump (45th President), have stars on the Walk. Reagan is also one of two Governors of California with a star; the other is Arnold Schwarzenegger.[119] One U.S. senator (George Murphy) and two members of the U.S. House of Representatives (Helen Gahagan and Sonny Bono) have stars. Ignacy Paderewski, who served as Prime Minister of Poland between the World Wars, is the only European head of government represented. Film and stage actor Albert Dekker served one term in the California State Assembly during the 1940s.[120][121]

On its 50th anniversary in 2005, Disneyland received a star near Disney's Soda Fountain on Hollywood Boulevard. Stars for commercial organizations are only considered for those with a Hollywood show business connection of at least 50 years' duration. While not technically part of the Walk itself (a city ordinance prohibits placing corporate names on sidewalks), the star was installed adjacent to it.[122]

There are four dogs represented on the walk, Lassie, Rin Tin Tin, Strongheart, and Snoopy.

Charlie Chaplin is the only honoree to be selected twice for the same star on the Walk. He was unanimously voted into the initial group of 500 in 1956, but the Selection Committee ultimately excluded him, ostensibly due to questions regarding his morals (he had been charged with violating the Mann Act—and exonerated—during the White Slavery hysteria of the 1940s),[123] but more likely due to his left-leaning political views.[124] The rebuke prompted an unsuccessful lawsuit by his son, Charles Chaplin Jr. Chaplin's star was finally added to the Walk in 1972, the same year he received his Academy Award.[38] Even then, 16 years later, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce received angry letters from across the country protesting its decision to include him.[125]

The committee's Chaplin difficulties reportedly contributed to its decision in 1978 against awarding a star to Paul Robeson, the controversial opera singer, actor, athlete, writer, lawyer, and social activist.[126] The resulting outcry from the entertainment industry, civic circles, local and national politicians, and many other quarters was so intense that the decision was reversed and Robeson was awarded a star in 1979.[127][128][129]

Fictional characters

editIn 1978, in honor of his 50th anniversary, Mickey Mouse became the first animated character to receive a star, and nearly twenty more followed over the next decades. Other fictional characters on the Walk include the Munchkins, the kaiju Godzilla, the live-action dog named Lassie, Pee-Wee Herman as portrayed by Paul Reubens,[130] animated film characters such as Shrek and Snow White, and animated television characters including the Simpsons and the Rugrats.

Jim Henson is one of four puppeteers to have a star, but also has a further three stars dedicated to his creations: one for The Muppets as a whole, one for Kermit the Frog and one for Big Bird.[131][132][133]

Errors

editIn 2010, Julia Louis-Dreyfus' star was constructed with the name "Julia Luis Dreyfus".[134] The actress was reportedly amused, and the error was corrected.[135] A similar mistake was made on Dick Van Dyke's star in 1993 ("Vandyke"), and rectified.[136] Film and television actor Don Haggerty's star originally displayed the first name "Dan". The mistake was fixed, but years later the television actor Dan Haggerty (of Grizzly Adams fame, no relation to Don) also received a star. The confusion eventually sprouted an urban legend that Dan Haggerty was the only honoree to have a star removed from the Walk of Fame.[137][138] For 28 years, the star intended to honor Mauritz Stiller, the Helsinki-born pioneer of Swedish film who brought Greta Garbo to the United States, read "Maurice Diller", possibly due to mistranscription of verbal dictation. The star was finally remade with the correct name in 1988.[139][140]

Four stars remain misspelled: the opera star Lotte Lehmann (spelled "Lottie");[141] King Kong creator, director, and producer and Cinerama pioneer Merian C. Cooper ("Meriam");[142] cinematography pioneer Auguste Lumière ("August");[143] and radio comedienne Mary Livingstone ("Livingston").[144]

Monty Woolley, the veteran film and stage actor best known for The Man Who Came to Dinner (1942) and the line "Time flies when you're having fun", is officially listed in the motion picture category,[145] but his star on the Walk of Fame bears the television emblem.[146] Woolley did appear on the small screen late in his career, but his TV contributions were eclipsed by his extensive stage, film, and radio work.[147][148][149] Similarly, the star of film actress Carmen Miranda bears the TV emblem,[150] although her official category is motion pictures.[151] Radio and television talk show host Larry King is officially a television honoree,[152] but his star displays a film camera.[153]

Theft and vandalism

editActs of vandalism on the Walk of Fame have ranged from profanity and political statements written on stars with markers and paint to damage with heavy tools.[154][155] Vandals have also tried to chisel out the brass category emblems embedded in the stars below the names,[156] and have even stolen a statue component of The Four Ladies of Hollywood.[157] Closed circuit surveillance cameras have been installed on the stretch of Hollywood Boulevard between La Brea Avenue and Vine Street in an effort to discourage mischievous activities.[158]

Four of the stars, which weigh about 300 pounds (140 kg) each, have been stolen from the Walk of Fame. In 2000, James Stewart's and Kirk Douglas' stars disappeared from their locations near the intersection of Hollywood and Vine, where they had been temporarily removed for a construction project. Police recovered them in the suburban community of South Gate when they arrested a man involved in an incident there and searched his house. The suspect was a construction worker employed on the Hollywood and Vine project. The stars had been badly damaged and had to be remade. One of Gene Autry's five stars was also stolen from a construction area. Another theft occurred in 2005 when thieves used a concrete saw to remove Gregory Peck's star from its Hollywood Boulevard site at the intersection of North El Centro Avenue, near North Gower. The star was replaced almost immediately, but the original was never recovered and the perpetrators never caught.[159]

Donald Trump's star, obtained for his work as owner and producer of the Miss Universe pageant,[160] has been vandalized multiple times.[161][162][163][164][157] During the 2016 presidential election, a man named James Otis, who claims to be an heir to the Otis Elevator Company fortune,[165][166] used a sledgehammer and a pickaxe to destroy all of the star's brass inlays. He readily admitted to the vandalism[167] and was arrested and sentenced to three years' probation.[168] The star was repaired and served as a site of pro-Trump demonstrations[169] until it was destroyed a second time in July 2018 by a man named Austin Clay.[170] Clay later surrendered himself to the police and was bailed out by James Otis.[171][172] Clay was sentenced to one day in jail, three years of probation, and 20 days of community service. He also was ordered to attend psychological counseling and pay restitution of $9,404.46 to the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce.[173] On December 18, 2018, the star was defaced with swastikas and other graffiti drawn in permanent marker,[174] and it was again vandalized with a pickaxe on October 2, 2020.[175]

In August 2018, the West Hollywood City Council unanimously passed a resolution requesting permanent removal of the star due to repeated vandalism, according to Mayor John Duran. The resolution was completely symbolic, as West Hollywood has no jurisdiction over the Walk.[176] Activist groups have also called for the removal of stars honoring individuals whose public and professional lives have become controversial, including Trump, Bill Cosby, Kevin Spacey, and Brett Ratner.[177] In answer to these campaigns, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce announced that because the Walk is a historical landmark,[Note 1] "once a star has been added ... it is considered a part of the historic fabric of the Hollywood Walk of Fame" and cannot be removed.[180]

Hollywood and La Brea Gateway

editThe Hollywood and La Brea Gateway is a 1993 cast stainless steel public art installation by architect Catherine Hardwicke.[181] The sculpture, popularly known as The Four Ladies of Hollywood, was commissioned by the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency Art Program as a tribute to the multi-ethnic women of the entertainment industry.[182] The installation consists of a square stainless steel Art Deco-style structure or gazebo, with an arched roof supporting a circular dome that is topped by a central obelisk with descending neon block letters spelling "Hollywood" on each of its four sides. Atop the obelisk is a small gilded weather vane-style sculpture of Marilyn Monroe in her iconic billowing skirt pose from The Seven Year Itch. The corners of the domed structure are supported by four caryatids sculpted by Harl West[182] representing African-American actress Dorothy Dandridge, Asian-American actress Anna May Wong, Mexican actress Dolores del Río, and Brooklyn-born actress Mae West.[183] The installation stands at the western end of the Hollywood Walk of Fame at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and North La Brea Avenue.[181]

The gazebo was dedicated on February 1, 1994, to a mixed reception. Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight called it "the most depressingly awful work of public art in recent years", representing the opposite of Hardwicke's intended tribute to women. "Sex, as a woman's historic gateway to Hollywood", he wrote, "couldn't be more explicitly described".[184]

Independent writer and film producer Gail Choice called it a fitting tribute to a group of pioneering and courageous women who "carried a tremendous burden on their feminine shoulders". "Never in my wildest dreams did I believe I'd ever see women of color immortalized in such a creative and wonderful fashion."[185] Hardwicke contended that critics had missed the "humor and symbolism" of the structure, which "embraces and pokes fun at the glamour, the polished metallic male form of the Oscar, and the pastiche of styles and dreams that pervades Tinseltown."[186]

In June 2019, the Marilyn Monroe statue above the gazebo was stolen by Austin Clay, who had vandalized Donald Trump's star a year earlier.[157]

Homage

editSome fans show respect for star recipients both living and dead by laying flowers or other symbolic tributes at their stars.[187] Others show their support in other ways; the star awarded to Julio Iglesias, for example, is kept in "pristine condition [by] a devoted band of elderly women [who] scrub and polish it once a month".[187]

The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has adopted the tradition of placing flower wreaths at the stars of newly deceased awardees; for example, Bette Davis in 1989,[188] Katharine Hepburn in 2003, and Jackie Cooper in 2011.[189] The stars of other deceased celebrities, such as Michael Jackson, Bruce Lee, Farrah Fawcett, Elizabeth Taylor,[190] Charles Aznavour,[191] Richard Pryor,[192] Ricardo Montalbán, James Doohan, Frank Sinatra,[193][194] Robin Williams,[195] Joan Rivers,[196] George Harrison,[197] Aretha Franklin,[198] Stan Lee,[199] and Betty White[200] have become impromptu memorial and vigil sites as well, and some continue to receive anniversary remembrances.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ While the Walk is individually a Los Angeles City Historical Monument, it is not registered by itself on the National Register of Historic Places. It is, instead, part of the Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment District's nomination to the National Register.[178][179]

References

edit- ^ a b "Tim Burton".

- ^ https://people.com/hollywood-walk-of-fame-rules-you-didnt-know-8431908#:~:text=Yes%2C%20it%20costs%20money%20to,of%20the%20Walk%20of%20Fame.

- ^ https://www.uspto.gov

- ^ a b Martin, Hugo (February 8, 2010). "Golden milestone for the Hollywood Walk of Fame". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "Licensing for the Walk of Fame | Hollywood Walk of Fame". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Walk of Fame Frequently Asked Questions". Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "Mike Myers gets a star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". Herald-Tribune. July 27, 2002. Archived from the original on July 28, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "Watch live as Daniel Craig gets Hollywood Walk of Fame star next to former James Bond Roger Moore". Entertainment Weekly. October 6, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "Ed O'Neill's Walk of Fame star in front of shoe store – Celebrity Circuit". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ Jim Manago (March 22, 2015). "Introduction". Behind Sach - The Huntz Hall Story. BearManor Media. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Thermos, Wendy (July 22, 2005). "Sidewalk Shrine to Celebrities Twinkles With Stars". Los Angeles Times. p. 2. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- ^ "Leno returns to scene of crime for Hollywood honor". Hurriyet Daily News. April 29, 2000. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017.

- ^ "Biographical information for George Carlin". Kennedy Center. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ Service, City News (November 30, 2018). "Lin-Manuel Miranda Receives Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". NBC Southern California. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Burnett, Carol (1986). One More Time (first ed.). New York: Random House. pp. 194–95. ISBN 0-394-55254-7.

- ^ a b "Special Stars – Page 1 – Hollywood Star Walk". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "Mayor gets Hollywood star". The Albany Herald. AP. June 26, 1993. p. 2A. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2020 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Lohdan, Tom (December 31, 2007). "Hollywood Walk Of Fame Stars – Mayor Tom Bradley". Flickr. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Beck, Charlie (May 10, 2006). "Hollywood Area". Los Angeles Police Department Blog. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023.

- ^ "The Star Categories". HWOF LLC. Archived from the original on March 5, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ a sixth category was added in 2023

- ^ a b c d Semuels, Alana (July 22, 2008). "Hollywood, brought to you by..." Los Angeles Times. p. B6. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020.

- ^ "L'Oreal Paris celebrates 100 years by helping to restore the Hollywood 'Walk of Fame'". Fashion Network. Reuters. October 14, 2009. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024.

- ^ Torrance, Kelly Jane (August 29, 2008). "Fame has its price". The Washington Times. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: Apollo Landing". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "History of the Walk of Fame". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Rozbrook, Roslyn (February 1998). "The Real Mr. Hollywood". Los Angeles Magazine. No. February 1998. p. 20. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c "The Hollywood Walk of Fame | A brief history in photos". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Lincoln Journal Star, June 27, 2006 – How do you get a Walk of Fame star? – The Associated Press Archived March 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ East Bay Times, July 1, 2006 – How stars get stars on Walk of Fame By Associated Press and Sandy Cohen Archived March 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Garcia, Courtney (June 11, 2012) "Out with Kodak, in with Dolby at home of Oscars" Archived May 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Reuters. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Townsend, Martin. "Los Angeles History – Extinct Restaurants & Cafes S-Z". LATimeMachines.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2006. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ Thomson, David (2006). The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood. Vintage. p. 149. ISBN 0-375-70154-0.

- ^ Williams, Gregory Paul (2006). The Story of Hollywood: An Illustrated History. BL Press. ISBN 978-0-9776299-0-9. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cohen, Sandy (June 30, 2006). "Price of Fame in Hollywood? $15,000". The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ^ "Bronze Stars Begot Grammy". The Robesonian. Lumberton, N.C. February 22, 1976. p. 13. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Judge Refuses Chaplin Walk of Fame Request". Los Angeles Times. August 11, 1960. p. B2. ProQuest 167734333. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Why doesn't Clint Eastwood have a star?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- ^ Conklin, Ellis E. (October 30, 1986). "Hollywood's Walk On The Mild Side Of Fame". Chicago Tribune. Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2011. (, )

- ^ "Walk of Whimsy". Daily News of Los Angeles (CA). Knight-Ridder, Mediastream. October 26, 1986. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2011.(subscription required) (text verif. Archived September 10, 2024, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Conklin, Ellis (October 30, 1986). "Top Stars Missing on Hall of Fame". Ottawa Citizen. Los Angeles Daily News. p. D17. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2020. (Google news archive)

- ^ Wanamaker, Marc (2009). Hollywood 1940–2008. Arcadia Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7385-5923-0. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ^ "Kramer First Name Put in Walk of Fame". Los Angeles Times. March 29, 1960. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ Shuitt, Doug (April 16, 1972). "Hollywood Blvd.---The Old Glamor Has Vanished". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Vincent, Roger (May 6, 2008). "Neighborhood face-lift gives Hollywood pause". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ^ "Walk of Fame". The Bulletin. UPI Telephoto. December 12, 1968. p. 20. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) Report – Community: Hollywood". City of Los Angeles: Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Jeff (January 11, 2008). "Honorary mayor of Hollywood dies". The Post and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina. AP. p. 2A.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Nomination Procedure". Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. June 8, 2002. Archived from the original on June 8, 2002.

- ^ a b ""Walk of Fame FAQs"". Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Official Site Of Johnny Grant, Hollywood's Honorary Mayor". johnnygrant.com. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Linkletter Installed as Hollywood 'Mayor'". Los Angeles Times. September 5, 1957. p. B6. ProQuest 167153542. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ del Barco, Mandalit (March 27, 2008). "Pin-Up Queen Turns Hollywood Mayor Race Pink". NPR. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Johnny Grant". HWOF LLC. Archived from the original on October 30, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ "Johnny Grant Remembered On The Hollywood Walk Of Fame". Life Magazine. January 10, 2008. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Johnny Grant's Bio". JohnnyGrant.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ^ ""Hollywood Walk of Fame" star". HWOF LLC. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ^ Bloom, David (December 4, 1996). "Rescuing Elvis : Roadwork steals shine from icon's 'flaming star'". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ Orlov, Rick (August 21, 1997). "Giving stars their due; associations press MTA to preserve Hollywood icons". Los Angeles Daily News (Free Online Library). Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ "Briefly: MTA told to save Walk of Fame tiles". Los Angeles Daily News (Free Online Library). September 4, 1997. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ "Michael Strahan to be Honored with First Hollywood Walk of Fame Sports Entertainment Star". Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Pool, Bob (July 22, 2008). "Walk of Fame going to have a little work done". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Pool, Bob (July 17, 2008). "Walk of Fame fix won't be easy stroll". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ "Alerts Archive". Only In Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Walker, Alissa (March 2, 2018). "Make the Oscars street closures permanent". Curbed LA. Archived from the original on September 8, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Crotty, Emilia (December 30, 2015). "Opinion: Here's a New Year's resolution worth keeping: Close Hollywood Boulevard to cars in 2016". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame's $4-Million Master Plan Moves Forward". Urbanize LA. June 14, 2019. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame Update Coming, City Selects Firm to Design Improvements". NBC Los Angeles. June 12, 2019. Archived from the original on September 8, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Nelson, Laura J.; Vega, Priscella (January 30, 2020). "L.A. considers bold makeover for Hollywood Boulevard: Fewer cars, bike lanes, wider sidewalks". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Barragan, Bianca (January 31, 2020). "'Exciting' Hollywood Boulevard makeover unveiled. But don't call it radical". Curbed LA. Archived from the original on September 8, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ "WALK OF FAME MASTER PLAN | Heart of Hollywood". Heartofhollywood.la. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame to Get Streetscape Improvements | KFI AM 640 | LA Local News". Kfiam640.iheart.com. July 28, 2022. Archived from the original on August 4, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame's $4-Million Master Plan Moves Forward". Urbanize LA. June 14, 2019. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ^ Service, City News (June 12, 2019). "City Selects Firm for Hollywood Walk of Fame Improvements". NBC Southern California. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Christian, Margena A. (April 16, 2007). "How Do You Really Get A Star On The Hollywood Walk Of Fame?". Jet Magazine. Vol. 111, no. 15. pp. 25, 29. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Donaldson-Evans, Catherine (December 3, 2003). "Hollywood Boulevard's Price of Fame". foxnews.com; News Corp. Archived from the original on June 29, 2006.

- ^ Duke, Alan (March 26, 2010). "Dennis Hopper attends Hollywood Walk of Fame ceremony". Cable News Network. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Pool, Bob (January 6, 1999). "Hollywood Tries to Help Stars Shine". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ "Academy Appoints Unger Communications Chief". Oscars.org. February 14, 2007. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- ^ "Walk of Fame 2011 Selection". hollywoodchamber.net. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. June 17, 2010. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

"It was not an easy job to winnow down the extra large number of nominations this year to reach these 30 names", said John Pavlik, chair of the Hollywood Walk of Fame Committee ...

- ^ Holmes, M (June 22, 2015). "Bradley Cooper, Quentin Tarantino Among Hollywood Walk of Fame 2016 Honorees". Variety.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame Class of 2024 Announced by Walk of Fame Chair Ellen K". Hollywood Walk Of Fame. Archived from the original on June 29, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ "A Star for the Greatest". Jet Magazine. Vol. 101, no. 6. January 28, 2002. p. 52. Archived from the original on September 7, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Ali Is Only Person With Hollywood Star on a Wall". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ^ Doran, Niall (June 4, 2016). "Why Ali Hollywood Star Is On The Wall Not The Floor". Archived from the original on January 12, 2020.

- ^ Sanello, Frank (UPI) (December 5, 1984). "Want your star on walk? It isn't easy". Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Halza, George (August 28, 1998). "Brolin, Streisand Revel in Stardom". pp. B8. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "Hollywood Star Walk: Who has the most stars on the Walk of Fame?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Gene Autry". Gene Autry Entertainment. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: Mickey Rooney". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: Jan & Mickey Rooney". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: Roy Rogers". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: Sons of the Pioneers". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt Earn Hollywood Walk of Fame Star". Rolling Stone. June 26, 2018. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ "Michael Jackson". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Paul McCartney to get his own star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". The Daily Star(UK). February 15, 2010. Archived from the original on February 19, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk: George Eastman". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Walt Disney". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Laura (April 12, 2010). "Top 10 Dubious Walk-of-Fame Stars: Disneyland". Time. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ "Alfred Hitchcock". October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ "Paul Henreid". October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on April 26, 2024. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ "Arlene Francis". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ "Walk of Fame Official Website: Cass Daley". October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on July 10, 2023. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Conklin, Ellis E. (November 2, 1968). "It's a Hollywood Walk of Shame". The Spokesman-Review. Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ "Sonny & Cher Walk of Fame Ceremony". Life Magazine. May 15, 1998. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Tommy Riggs". LA Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Brillhart, Ivan. "The 'MGM' Munchkin's". kansasoz.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- ^ "Harrison Ford (silent film actor)". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Harrison Ford". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Michael Jackson". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Michael Jackson (radio)". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Koerner, Brendan I. (November 18, 2003). "Who Gave Britney a Hollywood Star?". Slate.com. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ Weist, Jerry. Bradbury, an Illustrated Life: A Journey to Far Metaphor. New York: Morrow, 2002; ISBN 0-06-001182-3.

- ^ "George Eastman". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Thomas A. Edison". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Lee de Forest". Britannica. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Lee de Forest". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Braun, Hans-Joachim (Spring 1997). "Advanced Weaponry of the Stars". Invention & Technology. AmericanHeritage.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Warner, GA (October 28, 2010): Ronald Reagan sites in Southern California. Orange County Register archive. Retrieved March 21, 2013

- ^ "Autopsy Performed on Actor Albert Dekker". Los Angeles Times. May 7, 1968. p. 19.

- ^ Hare, William (2008). L.A. Noir: Nine Dark Visions of the City of Angels. McFarland. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7864-3740-5.

- ^ "Disneyland to get star treatment". L.A. Times. July 13, 2005. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Jerry Giesler, Pete Martin (2018). Hollywood Lawyer: The Jerry Giesler Story. Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 169. ISBN 9781789122541. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "On This Day: September 23, 1952: Charlie Chaplin Comes Home" Archived September 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Shuit, Doug (April 9, 1972). "Bitterness Survives 20 Years – They Haven't Given Up – Letter Writers Assail Chaplin". Los Angeles Times (archive). p. B2. ProQuest 156973192. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved August 31, 2010.(subscription required)

- ^ Thomson, David (2006). The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood. Vintage. pp. 164–5. ISBN 0-375-70154-0.

- ^ Qualles, Paris H. (August–September 1979). "What Price a Star? Robeson vs. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce". The Crisis. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Paul Robeson Gets a Star". Jet Magazine. Vol. 54, no. 23. August 24, 1978. p. 58. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ "At Long Last Hollywood Implants Robeson Star". Jet Magazine. Vol. 56, no. 7. May 3, 1979. p. 60. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Pee-wee Herman | Hollywood Walk of Fame". www.walkoffame.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ Heffley, Lynn; Oliver, Myrna (May 17, 1990). "Jim Henson". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ "Big Bird". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ "Kermit the Frog". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ "Julia Louis-Dreyfus Honored on walk of fame with a typo". Access Hollywood. May 4, 2010. Archived from the original on May 8, 2010.

- ^ Daniel, David (May 4, 2010). "Welcome to the Hollywood Walk of ... oops!". CNN. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ Epting, Chris (May 7, 2010). "Notorious Spelling Mistakes: Famous Mashed Words". AOLnews.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011.

- ^ Davidson, Bill (June 11, 1977). "Bozo and Dan are an Item!" (PDF). Archived April 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. TV Guide, p. 24. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ "Don Haggerty" Archived September 10, 2024, at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ "The Hollywood Walk of Fame : A brief history in photos, #6, Mauritz Stiller". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012.

- ^ Steve Harvey (April 15, 1988). "The 28-year mistake". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 6, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk – Lotte Lehmann" Archived May 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Arnold, Marvin. "Pilot of the Plane that Killed King Kong". Story Domain. Archived from the original on August 27, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Auguste Lumiere". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Mary Livingstone". Los Angeles Times Starwalk Project. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Monty Woolley". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on September 1, 2011. Retrieved May 20, 2011. Note: Official category is Motion Pictures but his star bears the television emblem.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk – Monty Woolley". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ "Monty Woolley Dies". St. Petersburg Times. May 7, 1963. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved January 12, 2016. via Google News

- ^ Hawes, William (2001). Filmed television drama, 1952–1958. McFarland & Company. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7864-1132-0.

- ^ "Monty Woolley to Appear in a Series of Television Films". Schenectady Gazette. NY. July 11, 1953. p. 8. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2020 – via Google News.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk – Carmen Miranda". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ "Carmen Miranda". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Larry King". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk – Larry King". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ Paul, Leigh (January 4, 2018). "10 Celebrities Whose Walk Of Fame Stars Were Vandalized". listverse.com. Listverse Ltd. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "Four Stars Vandalized On Hollywood Walk of Fame". sfvmedia.com. San Fernando News, Port Media Solutions LLC. November 21, 2018. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ Pool, Bob (November 30, 2005). "A Star is Torn from Boulevard". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c Fry, Hannah (June 25, 2019). "Marilyn Monroe sculpture thief previously took a pickax to Trump's star, police say". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Aundreia, et al (August 2008). "Measuring the Effects of Video Surveillance on Crime in Los Angeles" (PDF), p. 26. USC School of Policy, Planning, & Development. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ Pool, Bob (November 30, 2005). "A Star is Torn from Boulevard". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Zara, Christopher (October 26, 2016). "Why the heck does Donald Trump have a Walk of Fame star, anyway? It's not the reason you think". Fast Company. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Jackson, Henry C. (May 28, 2016). "Trump: A star is scorned". POLITICO. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (July 19, 2016). "Donald Trump's Walk of Fame Star Gets a Baby Border Wall (photos)". Archived from the original on July 20, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ "Protester uses Donald Trump Hollywood Walk of Fame star to mock him". CBS News. July 20, 2016. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Fry, Hannah (April 24, 2019). "Trump's star on Hollywood Walk of Fame is defaced by a vandal — again". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Parker, Ryan (July 26, 2018). "Man Who Destroyed Trump's Star in 2016 Offers Legal Help to New Alleged Vandal". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Gorman, Steve (February 21, 2017). "Elevator scion who defaced Trump's Hollywood star gets probation". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Man who destroyed Trump's star is 'proud' of his work". POLITICO. October 27, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Von Quednow, Cindy (February 21, 2017). "Man Sentenced to 3 Years Probation in Connection With Vandalizing Donald Trump's Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". KTLA.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Jennewein, Chris (October 30, 2016). "Trump supporters rally at repaired Hollywood Walk of Fame star". MyNewsLA.com. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Levenson, Eric; Chan, Stella (July 25, 2018). "President Trump's Walk of Fame star was smashed to pieces". CNN. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ Nashrulla, Tasneem (July 25, 2018). "Donald Trump's Star On The Hollywood Walk Of Fame Was Vandalized Again". BuzzFeedNews.com. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ Folley, Aris (July 25, 2018). "Man who vandalized Trump's Walk of Fame star bailed out by person who did it years ago: report". The Hill. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ "Trump Walk of Fame Star Vandal Sentenced to Jail, Probation". The Hollywood Reporter. November 7, 2018. Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "President Trump's Walk Of Fame Star Vandalized Yet Again". cbslocal.com. CBS Broadcasting, Inc. December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Donald Trump's Hollywood Walk of Fame star vandalized again". The Guardian. October 2, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Emily. "Council Fight To 'Totally Remove' Donald Trump's Hollywood Star". Unilad. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Phelan, Paige (July 10, 2015). "Bill Cosby, Donald Trump and 7 More Scandalous Stars Immortalized on Hollywood's Walk of Fame". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List - City Declared Monuments" (PDF). p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

194 Hollywood Walk of Fame - Hollywood Boulevard (between Gower and La Brea) & Vine Street (between Sunset and Yucca) - 07/05/1978 Hollywood 13

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form - Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment District". April 4, 1985. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

In addition to architectural details, there are several fine urban design features: colored terrazo entryways, neon signage, and the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

- ^ Ryder, Taryn (November 15, 2017). "Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has no plans to remove Walk of Fame stars amid sexual misconduct scandals". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ a b Deioma, Kayte. "Hollywood La Brea Gateway – The Four Ladies Statue". Golosangeles.about.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Hollywood and La Brea Gateway (sculpture)". Smithsonian American Museum Art Inventories Catalog. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "The Silver Women" (photo montage)". JustAboveSunset.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ Knight, Christopher (January 19, 1994). "Caution: Bad Art Up Ahead". Los Angeles Times (archives). Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Choice, Gale (February 14, 1994). "These Women Were Dreamers and Doers". Los Angeles Times (archives). Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Hardwicke, Catherine (February 14, 1994). "Critic Missed the Humor and Symbolism". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Halpern, Jake (2006). Fame junkies: the hidden truths behind America's favorite addiction. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-618-45369-6.

- ^ "Floral Tribute to Late Actress". The Union Democrat. October 10, 1989. p. 5A. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2020 – via Google News.

- ^ "'Superman' Daily Planet actor Jackie Cooper dies". Google News. (AFP). May 4, 2011. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014.

- ^ "Elizabeth Taylor: Walk of Fame deluged by flowers". The Telegraph (UK). March 24, 2011. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- ^ "Mort de Charles Aznavour : l'émotion palpable jusqu'à Hollywood". French Morning. October 3, 2018. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, George M. (December 15, 2005). "Richard Pryor Influence Is Unforgettable". The Vindicator. Knight-Ridder. p. D5. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2020.(Google News arch)

- ^ "Sinatra's death brings sales surge for his music". Star-News. May 18, 1998. p. 2A. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2020 – via Google News.

- ^ Waxman, Sharon; Span, Paula (May 16, 1998). "Across America, A Plaintive Note Of Mourning". The Washington Post. p. A1. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ^ "Fans mourn death of Robin Williams on Hollywood Walk of Fame". LA Times. August 12, 2014. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Tributes, flowers mount before Joan Rivers' funeral". ksdk.com. September 5, 2014. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Harrison Remembered At Hollywood Walk Of Fame". Lodi News-Sentinel. AP. December 1, 2001. p. 16. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2020 – via Google News.

- ^ Stallworth, Leo; Miracle, Veronica (August 17, 2018). "Aretha Franklin fans honor 'Queen of Soul' with flowers, crown at singer's Hollywood Walk of Fame star". ABC7 Los Angeles. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Flood, Alison (November 14, 2018). "Stan Lee was working on a new superhero called Dirt Man, says daughter". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame memorial for Betty White scheduled for Friday afternoon". FOX 11. December 31, 2021. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

External links

edit- Official website

- Hollywood Chamber of Commerce Walk of Fame videos – YouTube

- Hollywood Chamber of Commerce

- Hollywood Star Walk map: Los Angeles Times

- Hollywood Star Walk list: Los Angeles Times

- Hollywood Star Template