Holyhead (/ˌhəʊliˈhɛd, ˌhɒliˈhɛd/;[3][4] Welsh: Caergybi Welsh pronunciation: [kɑːɨrˈɡəbi] , "Cybi's fort") is a historic port town, and is the largest town and a community in the county of Isle of Anglesey, Wales. Holyhead is on Holy Island, bounded by the Irish Sea to the north, and is separated from Anglesey island by the narrow Cymyran Strait, having originally been connected to Anglesey via the Four Mile Bridge.[5]

Holyhead

| |

|---|---|

Town skyline | |

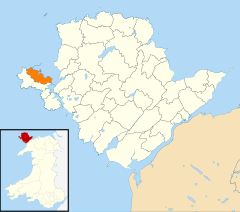

Location within Anglesey | |

| Population | 12,084 2011 Census[1] |

| OS grid reference | SH2482 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Preserved county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HOLYHEAD |

| Postcode district | LL65 |

| Dialling code | 01407 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

In the mid-19th century, Lord Stanley, a local philanthropist, funded the building of a larger causeway,[6] known locally as "the Cobb". it now carries the A5 and the railway line. The A55 dual carriageway runs parallel to the Cobb on a modern causeway.[7]

The town houses the Port of Holyhead, a major Irish Sea port for connections towards Ireland.[8] The population of the town proper as of the 2021 census was 12,084, an increase on the 2011 census.[9][better source needed]

Etymology

editThe town's English name, Holyhead, has existed since at least the 14th century. As is the case with many coastal parts of Wales, the name in English is significantly different from its name in Welsh. It refers to the holiness of the locality and has taken the form Haliheved, Holiheved, Le Holyhede and Holy Head in the past. The Welsh name, Caergybi, derives from the fortification around which the town developed. The locality was known by such names as Karkeby ('seat of Cybi'), Castro Kyby ('the fortified military camp of Cybi'), and Kaer Gybi (Cybi's resting place).[10]

Prior to the influence of the fort on the name, the hamlets which came before it were likely known as Llan y Gwyddel ('church/parish of the Irish') and Eglwys y Beddi ('church of the graves').[11]

History

editPrehistoric and Roman history

editHolyhead Old Town is built around St Cybi's Church, which is built inside one of Europe's few three-walled Roman forts (the fourth boundary being the sea, which used to come up to the fort). The Romans also built a watchtower on the top of Holyhead Mountain inside Mynydd y Twr, a prehistoric hillfort.[12]

Settlements in the area date from prehistoric times, with circular huts, burial chambers and standing stones featuring in the highest concentration in Britain. The current lighthouse is on South Stack on the other side of Holyhead Mountain.[13]

Soldiers Point Hotel, located near the breakwater park in Holyhead, was first established in 1848. The residence of an engineer was in charge of the government-sponsored alterations to Holyhead Harbour being carried out. It was badly damaged in a fire in 2011.[14]

Heritage Conservation Areas

editHolyhead has three officially designated Conservation Areas. Holyhead Central Conservation Area covers the historic Old Town core that developed around the Roman Fort. Holyhead Beach Conservation Area in located in the Newry promenade area, and Holyhead Mountain Conservation Area is located north of the village of Llaingoch.[15]

Transport history

editPort

editIn the early nineteenth century, it was still undecided which port would be chosen as the primary sea link along the route from London to Dublin: Porthdinllaen, on the Llŷn Peninsula, or Holyhead in Anglesey. In May 1806, a parliamentary bill approved new buildings in Porthdinllaen when it seemed that the town would be chosen. Porthdinllaen was almost as far west as Holyhead, but Holyhead was more accessible because of Thomas Telford's road developments. Porthdinllaen Harbour Company was formed in 1808 in preparation, but the bill before Parliament to constitute Porthdinllaen as a harbour for Irish trade was rejected in 1810.[16]

Holyhead's maritime importance was at its height in the 19th century with a 1+3⁄4-mile-long (2.8-kilometre) sea breakwater. Holyhead Breakwater, built to create a safe harbour for vessels caught in stormy waters on their way to Liverpool and the industrial ports of Lancashire; it is the longest breakwater in the UK.[17]

Throughout the later 18th century and the entire 19th century, Holyhead was a crucial transit point for landed gentry and British parliamentarians and military officials who were travelling from Ireland to London. It was also a transit point for British owners of multinational estates visiting their 'other lands' or London houses. The port of Holyhead saw significant development throughout the 19th century to accommodate the growing passenger traffic between Holyhead and Dublin, which reached approximately 14,000 passengers annually by 1814. Key improvements made after the 1800 Act of Union with Ireland included the illumination of the South Stack Lighthouse in 1809, the construction of a built-up harbor in 1810, and the addition of a substantial breakwater between 1848 and 1873. Although mail service through Holyhead was temporarily suspended in 1838 in favour of rail transport through Liverpool, the development of the north Wales coastal railway in 1850 led to its reinstatement.[18]

Road

editThe post road built by Thomas Telford from London strengthened Holyhead's position as the port from which the Royal Mail was dispatched to and from Dublin on the Mail coach. The A5 terminates at Admiralty Arch (1822–24), which was designed by Thomas Harrison to commemorate a visit by King George IV in 1821 en route to Ireland and marked the zenith of Irish Mail coach operations. Holy Island and Anglesey are separated by the Cymyran Strait which used to be crossed on the Four Mile Bridge; so called, because the bridge was 4 miles (6 kilometres) from Holyhead on the old turnpike.[5]

Railway

editWith the opening of the railway from London to Liverpool, Holyhead lost the London-Dublin mail contract in 1839 to the Port of Liverpool. Only after the completion of the Chester & Holyhead Railway in 1850, and the building of Holyhead railway station, did the Irish Mail return to Holyhead, operated from London Euston by the London & North Western Railway.[19]

Transport

editThe Port of Holyhead is a busy ferry port. Stena Line, Northern Europe's biggest ferry company, operates from the port, as do Irish Ferries. Ferries sail to Dublin.

Holyhead railway station is the terminus of the North Wales Coast Line and is currently served by Avanti West Coast and Transport for Wales services. Avanti West Coast runs direct trains to London Euston via Crewe[20] and Transport for Wales operate direct trains to Cardiff and Birmingham International, via Wrexham and Shrewsbury; they also operate on the route to Manchester Piccadilly, via Warrington.[21]

The rail and ferry terminals are connected (for pedestrians and cyclists) to the town centre by The Celtic Gateway bridge.[22]

The Stanley Embankment, or The Cob, connects Anglesey and Holy Island. It carries the North Wales Coast Line railway and the A5 road. The embankment was designed and built by Thomas Telford. When the A5 was being constructed between London and the Port of Holyhead, a more direct route was needed. Construction started in 1822 and was completed a year later.[23] It gets its formal name after John Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley of Alderley, a significant local benefactor.[6]

In 2001, work was completed on the extension of the A55 North Wales Expressway from the Britannia Bridge to Holyhead, giving the town a dual carriageway connection to North Wales and the main British motorway network. The A55 forms part of Euroroute E22. The Anglesey section was financed through a Private Finance Initiative scheme.[24]

Local bus services are provided primarily by Arriva Buses Wales, who operate services around Anglesey and to Bangor.[25]

Industry

editUntil September 2009, Holyhead's main industry was the massive aluminium smelter on the outskirts of the town, operated by Anglesey Aluminium, a subsidiary of Rio Tinto. A large jetty in the harbour received ships from Jamaica and Australia, and their cargoes of alumina were transported on a rope-driven conveyor belt running underneath the town to the plant. The jetty is now available to dock visiting cruise ships.[26]

The plant relied for its electricity supply on Wylfa nuclear power station, near Cemaes Bay. However, Wylfa was reaching the end of its life and had permission to generate only until 2012.[27] On 18 October 2010, the British government announced that Wylfa was one of the eight sites it considered suitable for future nuclear power stations.[28]

Holyhead Port is a major employer, most of the jobs linked to ferry services to the Republic of Ireland operated by Stena and Irish Ferries. Other significant industrial/transport sector employers in Holyhead include Holyhead Boatyard, Gwynedd Shipping and Eaton Electrical, with the last of these having seen many job losses in 2009.[29]

Until the end of 2020 the port, which employs 250 (in 2021), was the second busiest roll-on roll-off port in the UK after Dover with around 450,000 lorries taking ferries to Dublin. Following the Brexit withdrawal agreement, freight traffic from Ireland fell by 50% in January 2021.[30]

Climate

editLike the rest of Wales and the British Isles, Holyhead has a maritime climate (Cfb according to the Köppen climate classification) with cool summers and mild winters, and often high winds exacerbated by its location by the Irish Sea. The nearest official weather observation station is at RAF Valley, about five miles (eight kilometres) southeast of the town centre.[31]

On 23 November 1981, Holyhead was struck by two tornadoes during the record-breaking 1981 United Kingdom tornado outbreak. One of the tornadoes, rated as an F2/T4 tornado, was the strongest recorded out of 104 tornadoes in the entire outbreak, causing damage to around 20 properties in Holyhead and destroying a mobile home.[32]

| Climate data for RAF Valley (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

3.6 (38.5) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 74.6 (2.94) |

62.0 (2.44) |

57.0 (2.24) |

54.4 (2.14) |

52.4 (2.06) |

57.1 (2.25) |

57.4 (2.26) |

69.2 (2.72) |

73.9 (2.91) |

101.6 (4.00) |

103.3 (4.07) |

93.3 (3.67) |

856.3 (33.71) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 14.1 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 13.9 | 16.3 | 15.8 | 144.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60.6 | 85.1 | 131.7 | 181.8 | 233.4 | 219.3 | 205.5 | 187.9 | 150.7 | 107.9 | 62.5 | 48.3 | 1,674.7 |

| Source: Met Office[33] | |||||||||||||

Governance

editThere are two tiers of local government covering Holyhead, at community (town) and county level: Holyhead Town Council and Isle of Anglesey County Council. The town council is based at Holyhead Town Hall on Newry Street. It comprises sixteen councillors elected from the seven community electoral wards.[34]

Administrative history

editThe ancient parish of Holyhead covered the majority of Holy Island.[35] In 1832 a parliamentary borough was established covering just the area around the town itself, as a contributory borough to the Beaumaris Boroughs constituency.[36]

In 1860 a local government district was created covering the same area as the parliamentary borough, governed by an elected local board.[37] Such local government districts were reconstituted as urban districts under the Local Government Act 1894. As part of the 1894 reforms, parishes were no long allowed to straddle district boundaries, and so the part of Holyhead parish outside the urban district became a separate parish called 'Holyhead Rural'.[38]

Holyhead Town Hall was completed in 1875 and served as both a public events venue and meeting place for the local board and the urban district council which replaced it.[39][40] Holyhead Urban District was abolished in 1974, with its area instead becoming a community. District-level functions passed to Ynys Môn-Isle of Anglesey Borough Council, which in 1996 was reconstituted as a county council.[41][42] The Holyhead Rural parish also became a community in 1974, and was renamed Trearddur in 1984.

Notable people

edit- Captain John Macgregor Skinner (1761–1832) moved to Holyhead from the US in 1793. Master on packet ships between Holyhead and Dublin but was washed overboard. The town erected an obelisk in his honour[43] and his house is an exhibit at the Holyhead Maritime Museum.[44]

- John Walpole Willis (1793–1877), a Welsh-born judge, and a judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales

- Sir Ralph Champneys Williams (1848–1927) colonial governor of the Windward Islands & Newfoundland.

- Lillie Goodisson (1860–1947), a Welsh Australian nurse and a pioneer of family planning in New South Wales

- Francis Dodd (1874–1949), a British portrait painter, landscape artist and printmaker

- John Russell (1893–1917) winner of the Victoria Cross, was born in the town

- Ceinwen Rowlands (1905–1983), a Welsh concert soprano and recording artist

- R. S. Thomas (1913–2000), a Welsh poet and Anglican priest poet, grew up in Holyhead

- Cledwyn Hughes, Baron Cledwyn of Penrhos (1916–2001) MP & politician; attended Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi

- Barbara Margaret Trimble (1921–1995) a British writer of over 20 crime, thriller and romance novels

- David Crystal (born 1941) linguist and chair of the charity behind Holyhead's Ucheldre Centre, lives in Holyhead

- Glenys Kinnock (1944-2023) a politician, MEP, educated at Holyhead High School

- Dawn French (born 1957) comedian and actress, co-star in French and Saunders

- Albert Owen (born 1959) politician, MP for Ynys Môn from 2001 to 2019.

- Kevin Johnson (born 1960) is a managing partner at Medicxi Ventures, a venture capital firm

- Jason Evans (born 1968), a Welsh photographer and lecturer on photography

- Ben Crystal (born 1977), an English actor, author, and producer brought up in the town

- Gareth Williams (1978–2010) worked for GCHQ and SIS died in suspicious circumstances

Sport

edit- Donough O'Brien (1879–1953), was a Welsh-born Irish cricketer.

- Ray Williams (born 1959), is a weightlifting Commonwealth Games gold medallist.

- Tony Roberts (born 1969), is Welsh international footballer with 614 club caps

- Gareth Evans (born 1986), weightlifter, Commonwealth gold medalist and 2012 Summer Olympics, lives in the town.

- Alex Lynch (born in 1995), a footballer with over 100 club caps, educated in Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi.

Culture and sport

editHolyhead's arts centre, the Ucheldre Centre, is located in the chapel of an old convent belonging to the order of the Bon Sauveur. It holds regular art exhibitions, performances, workshops and film screenings. Holyhead Library is located in the old market hall. The Holyhead Maritime Museum is housed in what is claimed to be Wales's oldest lifeboat house. The lifeboat station was established in 1828.[45] The 1927 National Eisteddfod was held in the town. Holyhead High School (previously County Secondary school) was the first comprehensive school in the UK.[46]

According to the United Kingdom Census 2001, 47% of the residents in the town can speak Welsh. The highest percentage of speakers is in the 15-year-old age group, of whom 66% can speak the language. According to the 2011 Census, of those in the community who were born in Wales, 52.2% of the population could speak Welsh.[47]

The town's main football team is called Holyhead Hotspur, and they play in the Cymru North, the second tier of Welsh football, with their reserves playing in the Gwynedd League. Caergybi F.C. plays in the sixth tier Anglesey League. Holyhead Sailing Club provides members with facilities for sailing and kayaking with swinging moorings, a dinghy park and a clubhouse with a restaurant and bar. It is on Newry Beach in the historic port of Holyhead. Holyhead & Anglesey Amateur Boxing Club was founded on 1 April 2012, located in Vicarage Lane, Holyhead. The club is open to anyone over the age of 10, having a class for male and female trainees. Holyhead's cliffs are used for coasteering, a water sport which involves jumping off cliffs at different heights. Holyhead is the start and finish point of the Anglesey Coastal Path.[48]

Holyhead was officially twinned with Greystones, County Wicklow on 20 January 2012, and this is celebrated on a new road sign.[49]

References

edit- ^ "Parish Headcounts: Isle of Anglesey". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Holyhead Town Council". holyheadtowncouncil.com.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b Cathrall, William (1851). Wanderings in North Wales: A Road and Railway Guide-book : Comprising Curious and Interesting Historical Information with a Description of the Ancient Castles and Ruins of the Northern Principality, Its Churches, Towns, Mountains, Rivers, Lakes, Railways, Etc. William S. Orr and Company. p. 136.

- ^ a b Hughes, Margaret: "Anglesey from the sea", page 73. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2001

- ^ "Aerial View of Llandudno, Clwyd". Getty Images. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Phil Carradice (20 June 2011). "The opening of Holyhead's new harbour". BBC Blogs - Wales. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ Owen, Hywel Wyn (2015). The Place-Names of Wales. University of Wales Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1783161652.

- ^ Jones, Gwilym; Roberts, Tomos (1996). Enwau Lleoedd Môn : The Place-Names of Anglesey. Bangor, Wales: University of Wales Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0-904567-71-0.

- ^ "Holyhead Mountain Hut Group". Pegasus Archive. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "South Stack Lighthouse". trinityhouse.co.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ "Soldiers Point Hotel (15867)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Conservation Area Character Appraisal".

- ^ "Porthdinllaen Harbour Company Records". Archifau Cymru. National Library of Wales. 1806–1911. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Denton, A., & Leach, N. (2008). Lighthouses of Wales. Landmark Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84306-459-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coward, Adam N. (2023). "CONNECTIONS BETWEEN WELSH AND IRISH LANDED ESTATES, c.1650–c.1920: A PRELIMINARY OVERVIEW". Welsh History Review/Cylchgrawn Hanes Cymru. 31 (4): 558–560. doi:10.16922/whr.31.4.2 – via Ingenta Connect.

- ^ Famous named trains abolished The Railway Magazine issue 1216 August 2002 page 14

- ^ "Our latest timetable and ticket info". Avanti West Coast. May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Timetables". Transport for Wales. May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "The Celtic Gateway Bridge". Structurae. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Thomas Telford: The Road to Holyhead". cyclingnorthwales.co.uk.

- ^ "A55 Llandegai to Holyhead Trunk Road". PPP Forum. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Bus Services". Bus Times. May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Acquisition of former Anglesey Aluminium site welcomed". Isle of Anglesey County Council. 21 September 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Wylfa to continue generating until 2012". Nuclear Engineering International. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ "Nuclear power: Eight sites identified for future plants". BBC News. BBC. 18 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ "Holyhead factory closure could put 265 jobs at risk". Daily Post. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Partridge, Joanna (20 February 2021). "Ports feel the chill as trade re-routes around Brexit Britain". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "Severe Weather Payments". Hansard. 19 January 1987. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Apsley, Miriam L.; Mulder, Kelsey J.; Schultz, David M. (2016). "Reexamining the United Kingdom's Greatest Tornado Outbreak: Forecasting the Limited Extent of Tornadoes along a Cold Front" (PDF). Weather and Forecasting. 31 (3): 853–875. Bibcode:2016WtFor..31..853A. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-15-0131.1.

- ^ "Valley (Isle of Anglesey) UK climate averages - Met Office". Met Office. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ "Councillors". Holyhead Town Council. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Holyhead Ancient Parish / Civil Parish". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832. 1832. p. 370. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ "No. 22341". The London Gazette. 30 December 1859. p. 4883.

- ^ "Holyhead Urban District Council - Additional Deposit". JISC Archives Hub. Anglesey Archives. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ "Opening of the Holyhead Town Hall". The North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser. 4 September 1875. hdl:10107/4514500. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "No. 45415". The London Gazette. 2 July 1971. p. 7162.

- ^ Local Government Act 1972

- ^ Local Government (Wales) Act 1994

- ^ Holyhead.com Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 15 February 2015

- ^ Holyhead Maritime Museum Accessed 15 February 2015

- ^ "RNLI: Holyhead". Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "Are comprehensive schools still working for our pupils?". ITV. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "O'r rhai a anwyd yng Nghymru, % yn gallu siarad Cymraeg". Statiaith.

- ^ "Anglesey Coastal Path". Long Distance Walkers Association. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Everett, Cliff (23 January 2012). "Twinning Oath Signed". holyheadtowncouncil.com. Holyhead Town Council. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2012.