The hydrography of the Biella region, that is, the distribution of surface water in the province of Biella, Italy, falls almost entirely in the two basins of the Cervo and Sessera rivers, both tributaries of the Sesia. Some areas of the southwestern Biella region, on the other hand, are tributaries of the Dora Baltea; the largest natural body of water in the province, Lake Viverone, is also located in this area.[3] In addition to the natural bodies of water, there are several irrigation canals in the plains built mainly to support rice cultivation and some reservoirs built in the foothills.[4] In addition to irrigation, surface water is also used in the Biella area to serve the region's numerous industries and for potable water use, because the area is densely inhabited and groundwater capture is insufficient. Hydroelectric use, on the other hand, is very limited and is substantially confined to the Sessera Valley.[5] The streams of the Biella region can be subject to ruinous floods as well, which have caused numerous damage to property and people over time.[6]

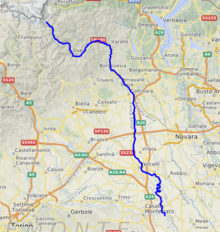

| Sesia river | |

|---|---|

The river in the upper Valsesia | |

Location of the Sesia in Italy | |

| Location | |

| Country | Italy |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Alagna Valsesia |

| • elevation | 4,500 m (14,800 ft) |

| Mouth | Po |

• coordinates | 45°07′59″N 8°34′24″E / 45.13306°N 8.57333°E |

| Length | 139.6 km (86.7 mi)[1] |

| Basin size | 3,037.6 km2 (1,172.8 sq mi)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • average | (mouth) 70.4 m3/s (2,490 cu ft/s)[2] |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Po→ Adriatic Sea |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Sermenza, Mastallone, Pascone, Strona di Valduggia. |

| • right | Otro, Vogna, Artogna, Sorba, rio di Valmala, Sessera, Cervo, Naviglio di Ivrea (artificial canal), Bona, Marcova |

Paleogeography

editBefore the formation of the ridge and more generally of the Ivrea Morainic Amphitheatre, deposited at the outlet of the Aosta Valley during the last glaciations, the hydrographic network of the area that today constitutes the Province of Biella must have been completely different from the present one.[3]

Paleogeographical research (in particular by geologists Francesco Carraro[7] and Franco Gianotti[8]) in fact shows how in ancient times the Cervo, after leaving the alpine valley of the same name, headed decisively southward to flow into the Dora Baltea roughly where Verrone stands today. Instead, the ancient course of the Dora was shifted markedly further northeast than it is today. In this reconstruction, the Oropa and Elvo also probably went directly into the Dora, running parallel to the Cervo for a long stretch of plain.[3]

The small basin of the Viona would also have been a first-order tributary of the Dora Baltea but its course, instead of diverting eastward, would instead have taken it to join the Dora not too far from Ivrea.[9]

Nevertheless, the deposition of the enormous moraine apparatus of the Serra and of sedimentary beds to the east of it changed this configuration and gradually diverted the course of the Cervo eastward, eventually leading it to flow into the Sesia. Sediments transported by the Balteo Glacier also barred the way towards the Dora to the current right tributaries of the Cervo itself, thus also conveying their waters towards the Sesia basin. This complex realignment of the hydrographic network left as a remnant many of the sedimentary deposits that can be found up to an altitude of 800 m a.s.l. at the foot of the Biellese mountains as well as the Baragge, which would represent what remains of the lowland areas present in that ancient past.[3]

The deep incision in the rocky substrate produced by the ancient course of the Cervo River and preserved below the present sedimentary blanket is of considerable importance today because of the aquifers it contains, which can potentially be exploited for potable water use.[10]

Streams

editAmong the main streams in the province of Biella, 14 belong to the Cervo basin while only 2 flow into the Sessera. Their hierarchy can be highlighted with a tree view, where streams are shown as secondary branches of a tree whose stem represents the main stream. For example, the Chiebbia is a tributary of the Quargnasca, which in turn flows into the Strona di Mosso, a tributary of the Cervo.

The following list in parentheses indicates whether the stream flows into its main watercourse from the right (r) or left (l), and what its length is in km.

Sessera Basin

- Sessera (l; 35,46 km)[11]

- Ponzone (r; 10,00 km)[11]

- Strona di Postua (l; 14,13 km)[11]

Cervo Basin

- Cervo (l; 65,48 km)[11]

Hydrological regime

editThe streams in the Biellese area almost all have a typically pre-Alpine regime with autumn and spring floods and marked summer and winter low flows.[3] The water supply provided by melting winter snow accumulation (often abundant in the upper Cervo or Sessera valleys[5]) is exhausted relatively quickly during the spring due to the lower elevation reached by the Biellese Alps compared to the other Piedmont mountain ranges. [12] In the event of heavy rainfall, the streams in the area are subject to massive floods that in the past have caused very serious damage to people and buildings.[13]

The water regime of the lowland section of these streams is then altered, both quantitatively and as a distribution of flow rates over time, by the withdrawal operated by irrigation canals and the return of residual water from irrigation, particularly those served by spring and summer flooding of rice fields.[4]

Flood events

editPrecipitation data for the Biella area show that the prevailing rainfall regime is of alpine type exposed to the plains, in which rainfall is more abundant than in the inner parts of the Alpine chain. In the Sesia and Cervo basins, the highest average annual rainfall in the Po Valley region (even more than 2,000 mm/year) and the highest rainfall intensities are reached. All this leads to the formation of floods with flow rates that can also become massive due to the low permeability of the soils located at the head of the valleys.[14]

Sometimes these flood waves lead to the overflow of streams resulting in the flooding of surrounding areas. Among many such events, the most catastrophic one in the last 100 years occurred in 1968; the most extensive damage was located on the Strona riverbank in Mosso. On Saturday, November 2, 1968, 180.6 mm of rain fell in Trivero, and the following day as much as 305.6 mm. The impact on the territory of these values, already very high in themselves, was then aggravated by the fact that the rain, instead of being evenly distributed over the two days, was concentrated in the night between Saturday and Sunday. In Valstrona alone, the flood caused 58 deaths and more than 100 injuries. Hundreds of homes were totally destroyed or severely damaged, and the same fate was suffered by numerous industrial plants. As a result, many companies had to resort to lay-offs, which came to affect some 13,000 workers.[13]

Even outside the Strona Valley, the flooding torrents swept away bridges and roads and flooded vast expanses of territory; landslides and mudslides involved much of the Biella region and in particular the Sessera basin. Here, near the village of Ponzone (Trivero), a huge landslide poured over the local factories a large part of a hillside (Il Trucco), and carnage was avoided only because the factories were closed due to the public holiday.[13]

The following table shows the flow rates of some of the waterways measured on November 2, 1968, flow rates that for the gauging stations listed in 2002 still represented the highest figure in the available time series.[14]

| Stream and section | Subtended sup. (km2) | Maximum flow rate (m3/s)[note 1] | Maximum specific flow rate (m3/s/km2)[note 1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sessera to Coggiola | 98 | 932 | 9,51 |

| Ponzone's confluence with Sessera | 18,6 | 267 | 14,35 |

| Chiebbia to Vigliano | 10,2 | 86 | 8,43 |

| Quargnasca's confluence with Chiebbia | 28,6 | 390 | 13,64 |

| Strona di Mosso to Vallemosso | 32 | 704 | 22 |

| Strona di Mosso to Cossato | 39 | 772 | 19,79 |

The 1968 event was not an isolated one, and numerous other flood waves have caused flood events in the Biella area over time. Among the most notable ones in the last century are:

- May 1923: a flood of the Cervo River caused severe damage in Piedicavallo and Rosazza;[6]

- November 1951: widespread flooding throughout the Biella area and particularly in the Cervo Valley;[14]

- October and November 1976: numerous disruptions caused in particular by the flooding of Olobbia, Elvo, Oremo and Quargnasca;[6]

- September 1981: flooding in the upper Cervo Valley with damage caused mostly by the minor hydrographic network;[6]

- April 1986: a large landslide blocked the former SS 232 near Valle Mosso;[14]

- September 1993: after 36 hours of bad weather, a flood of the Cervo River caused the bypass bridge to collapse. There were no casualties thanks to a roadman who noticed the impending disaster and had the bridge closed half an hour before the collapse.[15]

- June 2002: heavy rainfall caused landslides and overflowing in the western Biella basins; the most serious damage occurred in the upper Cervo valley, while in the Oropa basin a landslide destroyed a long section of the access road to the Rosazza Tunnel.[16]

- October 2020: the flood event mainly affected the Strona di Mosso Valley and Sessera Valley, with very heavy damage especially to the road system.[17]

Lakes

editIn the hilly and mountainous part of the Biellese region there are numerous lakes, generally of small to medium size with the exception of Lake Viverone. The latter, with a surface area of almost 6 km2, is in fact the third largest lake in Piedmont and is an important tourist hub with numerous accommodation and recreational facilities located on its shores. The lake is located on the border with the Province of Turin (in fact, about 1/6 of its surface area falls within the municipality of Azeglio); a public boat line connects the main towns along the coast.[18]

Lakes in the Biella region can be grouped according to the event responsible for their formation into lakes of glacial origin, intermorainic lakes and artificial lakes. For the lakes in each of these groups, the elevation of the body of water, the outfall (where it is present and is sufficiently significant), and, when available, the area of the lake are given in parentheses; the three lists are not exhaustive and do not include many small lakes of exclusively local importance.[19]

Lakes of glacial origin

editThey are located in the mountainous belt of the province and occupy the small basins left by the cirque glaciers present in the Biellese Alps during the glacial episodes of the Middle and Upper Pleistocene.[20] These are small lakes located at altitudes above 1,800 m above sea level, often the destination of hiking routes.

The main lakes of this type are:

- Lago della Vecchia (1858 m, Cervo,[11] 0.06 km²[21])

- Mucrone Lake (1894 m, Oropa,[11] 0.02 km²[21])

Intermorainic lakes

editThey are located in depressions included between the moraine ridges abandoned during the episodes of advance and retreat of the huge glacier that in the Pleistocene ran through the valley of the Dora Baltea.[20] They are sometimes devoid of an outfall and, when it exists, it is activated only in case of exceptional floods. Remains pertaining to pile-dwelling villages dating back to prehistoric times have been found around these lakes.[22] In particular, the remains of a Bronze Age village and two ancient monoxyle pirogues, i.e., built from a single tree trunk, have been found near Lake Bertignano; the boats are preserved in the Museum of Antiquities in Turin.[23] Investigations by the Piedmont Archaeological Superintendency have also identified the presence of important prehistoric sites on the shores of Lake Viverone.[24]

Such bodies of water present in the Biella region are:

- Lake Viverone (230 m,[11] 5.72 km²[20])

- Lake Bertignano (377 m,[11] 0.09 km²[21])

- Lake Prè (690 m,[19])

- Lake Bosi or Roppolo (375 m[19])

Artificial lakes

editThey are formed by dams that bar a watercourse; most of these reservoirs were created in the hillside to store the water needed to irrigate the rice fields in the plains below during the summer. However, the water from some of these reservoirs today has a mixed use and is also used for drinking, energy or industrial purposes. In particular, the Ponte Vittorio reservoir, whose construction dates back to 1953, was created to serve the numerous industrial users in the Strona di Mosso Valley.[25]

The main artificial reservoirs in the province are:

- Lago delle Piane or Masserano (325 m, Ostola,[11] 0.43 km²[21])

- Lake of Ponte Vittorio or Camandona (692 m, Strona di Mosso,[12] 0.04 km²[21])

- Lake Ravasanella (325 m, Riale Ravasanella - Rovasenda,[12] 0.31 km²[21])

Canals

editThe Biella plain is crossed by numerous irrigation ditches and canals, such as the ditch of Buronzo, which originates from a branch on the hydrographic left of the Cervo near Castelletto Cervo and returns to it further downstream, now in the province of Vercelli. These canals were generally built to serve rice-growing, which is mainly concentrated in the southeastern part of the province.[27] The area on the hydrographic right of the Cervo is served by various canals including the Roggia Massa di Serravalle, which originates in Cerrione from the Elvo and, after crossing the municipality of Salussola, flows into the Roggia Marchesa. The latter originates instead from the Cervo, flowing into the stream itself further downstream, not far from Villanova Biellese. The Roggia Madama and Roggia Molinara also depart from the Cerrione area, which then descend into the plain below, dispersing into numerous minor branches.[28] Finally, in the southern area of Biella, the Vanoni Canal passes through, an important derivation of the Depretis Canal completed in 1958 to distribute water from the Dora Baltea in the lower part of the rice-growing district.[27]

In some cases it is difficult to distinguish between a natural watercourse and a canal as is the case, for example, with the Roggia Drumma and Ottina, which collect water from the Candelo and Benna moorlands and then flow down to the Cervo in a semi-natural pattern. For centuries through this system of canals there has been a transfer to the Biellese and Vercellese areas of water resources from the Dora Baltea,[4] the flow of which remains substantial even during the summer thanks to the contribution provided by the snowfields and glaciers of the Valdaostan Alps.

Various artificial canals are also present in the hilly area of the province, although with much smaller flows and dimensions than those in the plain. Among these, the Roggia del Piano and the Roggia del Piazzo, two mixed-use derivations of the Oropa Stream that served the city of Biella, have had considerable historical-urban importance in the past. The Roggia del Piazzo in particular is one of the oldest public works in the Biella area; in fact, it was born together with the district of the same name around 1160 and the cost of its construction was shared between Bishop Uguccione and the city of Biella.[29]

In addition to the canals built for irrigation purposes, there are a number of derivations for hydroelectric purposes in Biella, concentrated particularly in the Sessera Valley and feeding small power plants that serve local industrial plants.[30]

Watersheds

editThe Biellese territory is almost entirely included in the two basins of the Cervo and the Sessera, both tributaries on the orographic right of the Sesia River. The most downstream part of both basins falls within the province of Vercelli, however, and the confluence of many of its main tributaries into the Cervo also occurs in the Vercelli plain. Some areas of southwestern Biella, however, encroach into the Dora Baltea basin; this occurs in the Serra area and in the plains around Cavaglià.[12]

The following table shows a series of data on the watersheds of Biella's main streams, taken from the Water Protection Plan adopted by the Piedmont Region.[1][2]

| Stream | Basin area (km2) | Basin perimeter (km) | Average flow rate (l/s) | Average specific flow rate (l/s/km2) | Annual inflow (mm) | Runoff coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oropa | 25,3 | 27 | 1200 | 47,48 | 1777 | 0,84 |

| Strona di Postua | 37,8 | 32 | 1670 | 44,07 | 1750 | 0,79 |

| Sessera | 189,3 | 69 | 7510 | 39,68 | 1616 | 0,77 |

| Ingagna | 103,6 | 45 | 3400 | 33,03 | 1441 | 0,72 |

| Oremo | 28,3 | 32 | 860 | 30,52 | 1456 | 0,66 |

| Ponzone | 18,7 | 20 | 560 | 29,84 | 1422 | 0,66 |

| Viona | 20,2 | 35 | 500 | 26,6 | 1249 | 0,67 |

| Elvo | 300,0 | 107 | 6830 | 22,77 | 1243 | 0,58 |

| Bisingana | 24,7 | 27 | 540 | 21,85 | 1251 | 0,55 |

| Cervo | 1024,4 | 152 | 21910 | 21,39 | 1219 | 0,55 |

| Strona di Mosso | 101,7 | 49 | 2130 | 20,99 | 1195 | 0,55 |

| Marchiazza | 118,4 | 67 | 2380 | 20,14 | 1058 | 0,6 |

| Ostola | 65,0 | 42 | 1290 | 19,81 | 1207 | 0,52 |

| Rovasenda | 148,9 | 73 | 2940 | 19,74 | 1130 | 0,55 |

| Chiebbia | 16,0 | 25 | 300 | 18,67 | 1148 | 0,51 |

| Quargnasca | 47,9 | 29 | 850 | 17,71 | 1126 | 0,5 |

| Olobbia | 36,7 | 35 | 600 | 16,38 | 1072 | 0,48 |

While the average flow rate expressed in m3/s measures the total amount of water leaving the basin on average in the unit of time, the one expressed in liters/s-km2 measures the surface runoff water that is produced by each km2 of the same catchment, again in the unit of time. The latter figure is greater in mountain basins (e.g., those of Oropa or Strona di Postua) than in hill basins (e.g., Olobbia) due to a number of factors including greater land gradients that favor runoff at the expense of water infiltration into the soil[31] and lower evapotranspiration losses due to vegetation. For much the same reasons, higher runoff coefficients are also found in mountainous areas which, among other things, have higher annual water inflows (here expressed in mm) in this part of Piedmont.

Solid transport

editSolid transport is the ability of a watercourse to transport solid materials downstream. This transport can occur by various modes among which, in the climatic situation of the Biella region, suspension in water and rolling/dragging near the bottom largely predominate. In order to arrive at a quantitative estimate of the solid transport of a watercourse, it is necessary to know both the average amount of sediment produced by the upland portion of the basin of the watercourse itself and the solid transport capacity of the river channel.

The former depends on the lithological and tectonic characteristics of the area under consideration (rock erodibility, slope gradient, presence of structural fractures, etc.) as well as the local climate and, in particular, the amount and type of atmospheric precipitation.[32]

For the Elvo and Cervo mountain basins, which together cover an area of 426 km2, the average annual precipitation is 1,580 mm and the amount of sediment produced has been estimated at 35,600 m3 annually, or 0.08 mm/year of specific erosion. This figure is rather low when compared with the average value of specific erosion in the entire Po mountain basin (28,440 km2), which is estimated at 1.2 mm/year.[14] The amount of sediment originating from the Biella mountain basins is also evidently medium-low when compared with their surface area: compared with a territorial extension of the area considered that represents 4.94% of the Po Valley mountain area, the sediment produced by it is only 3.21% of the total.[14]

On the other hand, as far as estimating the solid transport capacity of river courses is concerned, it is necessary to consider not only the magnitude and duration of the watercourse's flow rates, but also the physical characteristics of its riverbed (slope, width, roughness, tortuosity, grain size of materials).[32]

The following table provides an estimate of the annual solid transport capacity of the two main streams in Biella and, for comparison, shows the same data referring to the Sesia River.[14]

| Water course | Bottom transport capacity (thousands of m3/year) | Suspended transport capacity (thousands of m3/year) | Total transport capacity (thousands of m3/year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervo | 9,0 | 14,7 | 23,7 |

| Elvo | 6,0 | 8,0 | 14,0 |

| Sesia | 44,9 | 66,4 | 111,3 |

From the comparison of the amount of sediment produced by a basin and the solid transport capacity of the river channel, rough predictions can be made about the prevalence of either deposition of transported materials or erosion, with the consequent deepening of the riverbed, abandonment of secondary branches, and a decrease in the rambling range of the watercourse. From the available data, it appears that the overall situation on the Elvo is fairly close to the equilibrium point, and that instead along the Cervo River channel erosion tends to predominate over deposition.[14]

Uses of water

editIndustry and hydropower

editIn the past, water availability favored the concentration of the textile industry near Biella's streams. Notable examples of industrial archaeology, such as the Biella factories located near the confluence of Cervo and Oropa or the Wheel Factory on the banks of the Ponzone Creek, remain as evidence of this historical phase.[33]

Water withdrawals for industrial use are still numerous, and tend to be concentrated in the hilly stretches and at the outlet on the plain of river courses, such as in the middle Strona valley of Mosso or in the lower Cervo Valley.

The discontinuity of the flows of Biella's streams, on the other hand, confines the hydroelectric use of its waters to limited mountainous areas such as the Sessera Valley; derivations are generally operated by private utilities that use the energy produced for the operation of their industrial plants.[30]

Irrigation

editTo alleviate at least part of the summer water shortage, a number of dams were built in the second half of the twentieth century that retain water from spring rainfall in a series of artificial lakes. These are then gradually restored over the summer, allowing irrigation of the underlying rice-growing area.

The main provider of this type of service is the Consorzio di Bonifica della Baraggia (Ovest Sesia).[21]

Potable water

editThe two main users of Biella's water for potable water purposes are CORDAR spa Biella Servizi, the company that manages, among other things, Biella's water supply, and Servizio Idrico Integrato S.p.a. (SII), which manages the water services of several municipalities in Vercelli and Biella including Borgosesia. They are joined by two other managers of integrated water services of supra-municipal importance, CORDAR Valsesia spa and Comuni Riuniti spa. In some municipalities, the presence of these utilities coexists with that of locally important aqueducts operated directly by local citizens; about ten municipalities lack an integrated water service for now. While the water supply of CORDAR spa Biella Servizi relies mainly on springs and wells a good part of the drinking water put on the network by Servizio Idrico Integrato S.p.a. comes instead from two artificial lakes, Lago delle Piane and Ingagna Lake. Some of this water, however, is not used directly by SII but is sold to CORDAR spa Biella Servizi.[5]

Also in the context of water use for human consumption, two important plants for collecting and bottling mineral water are worth mentioning, both located on the southern slopes of the Colma di Mombarone. These are Fonte Caudana, located in the municipality of Donato and operated by Alpe Guizza S.p.a.[34] (a brand of Acqua Minerale San Benedetto S.p.a.) and Acqua Lauretana. This second mineral water, which qualifies as the lightest in Europe,[35] is instead collected and bottled in the municipality of Graglia by Società Lauretana S.p.a.[36]

Other uses

editThe streams draining the Bessa area are known, as are other Piedmontese watercourses such as the Orco, for the presence of bits of gold in the bed sands.[37] Gold panning had in antiquity a very notable economic importance and led to the grandiose mining work put in place by the ancient Romans on the Bessa plateau, whose gold sediments were washed down thanks to the detour of the waters of the nearby streams Viona and Olobbia.[38] These streams are still known among avid gold prospectors for the presence of flecks of metal in their alluvial deposits, so much so that in August 2009 the municipality of Zubiena hosted the World Gold Prospecting Championships.[39]

The waters of Lake Viverone and those of the mountain section of some streams including the Cervo and Sessera are used during the summer for bathing.[40]

The streams in the Biellese region are not navigable by motor boats; however, it should be mentioned that there is a public lake transport line on Lake Viverone.[18] During periods when the flow is sufficiently high, however, it is possible to go down some streams by canoe or rafting, including the Sessera, the Strona di Postua,[41] and the Cervo.[42]

Many Biella streams, including lowland ones, are also valued fishing grounds.[43][44]

Environmental status

editWater quality monitoring in Biella is based on a network of 24 sampling stations (in 2006) managed by ARPA-Piemonte. The environmental status of streams in the Biellese region is generally satisfactory in the upland section but worsens considerably in the more anthropized hillside areas due to emissions from civil and industrial sources. The impact of pollutant factors tends to be more severe in streams with low flows and poor self-depurative capacity.[5] Even in the lowlands, due to water shortages caused by withdrawal for agricultural use and the presence of pesticide residues, the environmental status of Biella's streams generally remains unsatisfactory.[21]

Out of the total of 24 points surveyed in 2006, 4 were in S.A.C.A. class 4 (POOR) and only one was in class 5 (VERY POOR). The situation of Lake Viverone is also rather problematic mainly due to its slow water exchange. The lake became almost completely swimmable again in 2008 after several years during which this use had been prohibited due to pollution. For the time being, water quality remains rather poor, although a cleanup project currently being implemented could lead to a gradual improvement in quality.[5]

The main sewage treatment plant in the Biella area is the one operated by CORDAR spa Biella Servizi and is located near Cossato in Spolina. This plant has a capacity of 520,000 population equivalent (p.e.); in contrast, none of the many other sewage treatment plants in the Biellese area exceeds the capacity of 100,000 p.e..[5]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b While the average flow rate (expressed in m3/s or liters/s) measures the total amount of water flowing out of the basin on average in the unit of time (expressed in m3/s*km² or liters/s*km²), the specific flow rate, on the other hand, measures the surface runoff water that is produced by each km²

References

edit- ^ a b c d e AA.VV. (2004). "Elaborato I.c/5". Piano di Tutela delle Acque - Revisione del 1º luglio 2004; Caratterizzazione bacini Idrografici (PDF). Regione Piemonte. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2012-10-28. Cite error: The named reference "PTA_al5" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b AA.VV. (2004). "Elaborato I.c/7". Piano di Tutela delle Acque - Revisione del 1º luglio 2004; Caratterizzazione bacini Idrografici (PDF). Regione Piemonte. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2012-10-28. Cite error: The named reference "PTA_al7" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e Assessorato alla Pianificazione Territoriale della Provincia di Biella (2004). "Fisiografia e pericolosità ambientale". Variante n.1 al Piano Territoriale Provinciale - Matrice ambientale. Archived from the original (pdf) on May 5, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c AA.VV. (2007). "5 - Idrologia e idraulica". Bilancio delle disponibilità idriche naturali e valutazione dell’incidenza dei prelievi nel bacino del Fiume Sesia (pdf). Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f AA.VV (2006). Variante n. 1 al Piano Territoriale Provinciale della Provincia di Biella - Valutazione Ambientale Strategica (pdf). Provincia di Biella. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Tropeano (CNR/IRPI e GNDCI), Domenico. "Eventi alluvionali e frane in Italia Settentrionale". nimbus.it. Archived from the original on July 15, 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ Carraro, F.; Medioli, F.; Petrucci, F. (1975). Geomorphological study of the morainic Amphiteatre of Ivrea, Northwest Italy. R. Soc. New Zealand.

- ^ Gianotti, Franco (1993). Ricostruzione dell’evoluzione quaternaria del margine esterno del settore laterale sinistro dell’Anfiteatro Morenico d’Ivrea. Tesi di Laurea. Università di Torino.

- ^ Pedron, Roberto; Sedea, Roberto; Sottani, Andrea. Caratterizzazione geologica ed idrogeologica di un sistema acquifero fluvioglaciale per la produzione di acque minerali. Sinergeo.

- ^ Maffeo, Brunello. "Idrogeologia e strutture profonde dell'alta pianura biellese". Atti del convegno "Acqua in pianura preziosa quella profonda, talvolta troppa quella superficiale" (pdf). CORDAR spa Biella Servizi.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Sistema informativo dell'Autorità di bacino del fiume Po". Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Carta Tecnica Regionale raster 1:10.000 (vers.3.0) della Regione Piemonte - 2007

- ^ a b c Giovi, Angelo. Biellese: la catastrofica alluvione del novembre 1968. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h AA.VV. Linee generali di assetto idraulico e idrogeologico nel bacino del Sesia. Autorità di bacino del fiume Po. Archived from the original (pdf) on June 7, 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Ferrari, Elisabetta (August 21, 2018). "Venticinque anni fa il crollo del ponte della tangenziale". La Nuova Provincia di Biella. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ Giampani, C.; Girelli, C.; Piccioni, C. (2004). Evento alluvionale del 4-6 giugno 2002 nel territorio biellese (pdf). Arpa Piemonte. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Pria, Matteo (October 18, 2020). "Il Biellese orientale conta i danni dell'alluvione: "Dieci milioni per ricostruire"". La Stampa. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Carta dei sentieri della Provincia di Biella 1:25.00, Provincia di Biella, 2004

- ^ a b c AA.VV. (2007). "B2 L4 - Viverone o d'Azeglio". Piano di tutela delle acque (pdf). Regione Piemonte - Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i AA.VV. (2007). "AI 18 - Cervo". Piano di tutela delle acque (PDF). Regione Piemonte - Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche. Archived from the original (pdf) on October 29, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ Giovannacci Amodeo, Gabriella (1994). "Storia". Nuova guida di Biella e Provincia. Biella: Libreria Vittorio Giovannacci.

- ^ "Scheda su Viverone (Associazione Via Francigena)". Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ "Scheda Lago di Viverone su www.archeocarta.com". Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ Lago di Ponte Vittorio [Lago di Ponte Vittorio] (in Italian). Piemonte Expo. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

- ^ AA.VV. (2007). "AI 16 - Alto Sesia". Piano di tutela delle acque (PDF). Regione Piemonte - Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche. Archived from the original (pdf) on August 9, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ a b "Archivio storico on-line del Consorzio Ovest Sesia". Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Circolari, Claudio. "Il torrente Elvo". Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ AA.VV. (2005). Sentieri del Biellese per l'anno 2005. Biella: Consociazione Amici dei Sentieri del Biellese. Archived from the original (pdf) on May 26, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ a b AA.VV. (2004). "Inquadramento idrologico". Proprietà demaniale regionale della Val Sessera - Piano forestale aziendale [Proprietà demaniale regionale della Val Sessera - Piano forestale aziendale] (PDF) (in Italian). Turin: Istituto per le Piante da Legno e l'Ambiente - IPLA spa, Regione Piemonte. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2024-02-26. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ Brugioni & altri (2008). Determinazione dell'infiltrazione efficace alla scala di bacino finalizzata alla individuazione delle aree a diversa disponibilità di risorse idriche sotterranee (PDF). Autorità di bacino del Fiume Arno. Archived from the original (pdf) on April 27, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ a b AA.VV. Linee generali di assetto idrogeologico e quadro degli interventi - Bacino dell’Agogna (PDF). Autorità di bacino del fiume Po - Parma. Archived from the original (pdf) on May 26, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- ^ "DocBi - Centro Studi Biellesi". Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ "Bollettino Ufficiale n. 48 del 28 / 11 / 2002". Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ "Sito dell'acqua minerale Lauretana". Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2009."Sito dell'acqua minerale Lauretana". Archived from the original on August 28, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ "Bollettino Ufficiale n. 41 - Supplemento ordinario n. 1 del 12 ottobre 2006". Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ "Dal Fiume Elvo a Olobbia e dintorni: Oro e riflessioni; articolo on-line di Fabio Belloni". Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ "Sito sulla miniera romana della Bessa a cura di DocBi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 31, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ "Sito ufficiale del Comune di Zubiena". Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ "Pagina web sul Santuario del Cavallero". Archived from the original on March 25, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ "Rafting e sport fluviali in Valsesia". Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Fiume Cervo: Bogna di Quittengo - Miagliano su www.ckfiumi.net". Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Sito della Comunità Montana Valsessera". Archived from the original on July 12, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ "Articolo sul sito web Pescaonline". Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

Bibliography

edit- Giovannacci Amodeo, Gabriella (1994). "Idrografia". Nuova guida di Biella e Provincia. Biella: Libreria Vittorio Giovannacci.

- AA.VV. Linee generali di assetto idraulico e idrogeologico nel bacino del Sesia. Autorità di bacino del fiume Po. Archived from the original (pdf) on June 7, 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche (2003). Atlante dei laghi Piemontesi. Regione Piemonte.

- Giampani, C.; Girelli, C.; Piccioni, C. (2004). Evento alluvionale del 4-6 giugno 2002 nel territorio biellese (pdf). Arpa Piemonte. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- Provincia di Biella - Settore Pianificazione Territoriale e INGENIA sas (2004). Carta dei sentieri della Provincia di Biella 1:25.00 (fogli 1-5).

- AA.VV. (2004). Proprietà demaniale regionale della Val Sessera - Piano forestale aziendale. Turin: Istituto per le Piante da Legno e l'Ambiente - IPLA spa, Regione Piemonte.

- Variante n.1 al Piano Territoriale Provinciale - Matrice ambientale: fisiografia e pericolosità ambientale (pdf). Provincia di Biella - Assessorato alla Pianificazione Territoriale. 2004. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche (2007). Regione Piemonte (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- Direzione Pianificazione delle Risorse Idriche (2007). Piano di tutela delle acque (AI 16 - Alto Sesia) (PDF). Regione Piemonte. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- Regione Piemonte - Settore Cartografico (2007). Carta Tecnica Regionale raster 1:10.000 (vers.3.0 su CD).

- AA.VV. (2007). Bilancio delle disponibilità idriche naturali e valutazione dell’incidenza dei prelievi nel bacino del Fiume Sesia (PDF). Regione Piemonte. Retrieved October 1, 2009.