Paul Maurice Kelly AO (born 13 January 1955) is an Australian rock music singer-songwriter and guitarist. He has performed solo, and has led numerous groups, including the Dots, the Coloured Girls, and the Messengers. He has worked with other artists and groups, including associated projects Professor Ratbaggy and Stardust Five. Kelly's music style has ranged from bluegrass to studio-oriented dub reggae, but his core output straddles folk, rock and country. His lyrics capture the vastness of the culture and landscape of Australia by chronicling life about him for over 30 years. David Fricke from Rolling Stone calls Kelly "one of the finest songwriters I have ever heard, Australian or otherwise".[1] Kelly has said, "Song writing is mysterious to me. I still feel like a total beginner. I don't feel like I have got it nailed yet."[2]

Paul Kelly | |

|---|---|

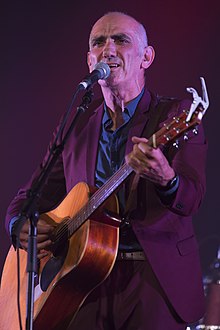

Kelly performing at Byron Bay Bluesfest on 6 April 2015 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Paul Maurice Kelly |

| Born | 13 January 1955 Adelaide, South Australia, Australia |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1974–present |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | paulkelly |

After growing up in Adelaide, Kelly travelled around Australia before settling in Melbourne in 1976. He became involved in the pub rock scene and drug culture and recorded two albums with the Dots. Kelly moved to Sydney by 1985, where he formed Paul Kelly and the Coloured Girls. The band was renamed Paul Kelly and the Messengers, initially only for international releases, to avoid possible racial interpretations of the word "coloured". At the end of the 1980s, Kelly returned to Melbourne, and in 1991 he disbanded the Messengers.

Kelly's Top 40 singles include "Billy Baxter", "Before Too Long", "Darling It Hurts", "To Her Door" (his highest-charting local hit in 1987), "Dumb Things" (appeared on United States charts in 1988) and "Roll on Summer". Top-20 albums include Gossip, Under the Sun, Comedy, Songs from the South (1997 compilation), ...Nothing but a Dream, Stolen Apples, Spring and Fall, The Merri Soul Sessions, Seven Sonnets and a Song, Death's Dateless Night (with Charlie Owen), Life Is Fine (his first number-one album) and Nature. Kelly has won 14 Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) Music Awards, including his induction into their hall of fame in 1997. Dan Kelly, his nephew, is a singer and guitarist in his own right. Dan performed with Kelly on Ways and Means and Stolen Apples. Both were members of Stardust Five, which released a self-titled album in 2006. On 22 September 2010, Kelly released his memoir, How to Make Gravy, which he described as "it's not traditional; it's writing around the A–Z theme – I tell stories around the song lyrics in alphabetical order".[3] His biographical film Paul Kelly: Stories of Me, directed by Ian Darling, was released to cinemas in October 2012.

In 2001, the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) listed the Top 30 Australian songs of all time, which included Kelly's To Her Door, and Treaty, written by Kelly and members of Yothu Yindi. Aside from Treaty, Kelly wrote or co-wrote several songs on Indigenous Australian social issues and historical events. He provided songs for many other artists, tailoring them to their particular vocal range. The album Women at the Well from 2002 had 14 female artists record his songs in tribute.

Kelly was appointed as an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2017 for distinguished service to the performing arts and to the promotion of the national identity through contributions as a singer, songwriter and musician.[4] Kelly was married and divorced twice; he has three children and resides in St Kilda, a suburb of Melbourne.

Early life and education

editPaul Maurice Kelly[5] was born on 13 January 1955 in Adelaide, to John Erwin Kelly, a lawyer, and Josephine (née Filippini), the sixth of eight surviving children.[6][7] According to Rip It Up magazine, "legend has it" that Kelly's mother gave birth to him "in a taxi outside North Adelaide's Calvary Hospital".[8]

Although Kelly was raised as a Roman Catholic, he later described himself as a non-believer.[9][10] He is the great-great-grandson of Jeremiah Kelly, who emigrated from Ireland in 1852 and settled in Clare, South Australia.[11] His paternal grandfather, Francis Kelly, established a law firm in 1917, which his father, John, joined in 1937.[12]

John Kelly died in 1968 at the age of 52, after having been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease three years earlier.[13] Paul Kelly was thirteen years old when his father died.[14] Kelly described his father: "I have good memories, he was the kind of father that, well, I missed him when he died very much. The older children were growing into him at the time he died. He was not well enough to play sport with me."[15][16]

Kelly's maternal grandfather was an Argentine-born, Italian-speaking opera singer, Count Ercole Filippini, a leading baritone for the La Scala Opera Company in Milan.[17]

Filippini was touring Australia in 1914 with a Spanish opera company when World War I broke out; Filippini stayed and later married Anne McPharland, one of his students.[11] As Countessa Anne Filippini, she was Australia's first female symphony orchestra conductor.[15] She sang the role of Marguerite in Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Radio Perth's performance of Faust in 1928.[17]

Kelly's grandparents started the Italo-Australian Opera Company, which toured the country in the 1920s.[18]

Josephine raised the younger children alone after John's death, but found time to assist others in need.[14] Paul's oldest sister, Anne, became a nun and went on to write hymns, while a younger sister, Mary-Jo, plays piano in Latin bands and teaches music.[19][20]

His eldest brother, Martin, worked for Edmund Rice International,[21][22] he passed in 2021 at the age of 69,[23] with another brother, Tony, a drug and alcohol counsellor, who ran as an Australian Greens candidate in the 2001 and 2004 federal elections.[24][25] Josephine Kelly moved to Brisbane, where she died in 2000 at the age of 76.[26]

Kelly attended Rostrevor College, a Christian Brothers school, where he played trumpet and studied piano, became the first XI cricket captain, played in the first XVIII football (Australian rules), and was named dux of his senior year.[27][28] He studied arts at Flinders University in 1973, but left after a term, disillusioned with academic life. He began writing prose and started a magazine with some friends.[29]

Kelly spent several years working odd jobs, travelling around the country and learning guitar before he moved to Melbourne in 1976.[30][31]

Career

edit1974–1984: Early career and with the Dots

editWhile travelling around Australia, Paul Kelly made his first public performance in 1974 in Hobart.[19][33] He later recalled:

I was living there at the time and there was a folk club at Salamanca Place. They had a night, I think a Monday night, where anyone could get up. I sang Dylan's "Girl from North Country" and "Streets of Forbes", a traditional Australian song about Ben Hall. I can't really remember how it went – I remember I had a lot to drink afterwards from relief. I was incredibly nervous.[34]

His first published song, "It's the Falling Apart that Makes You", was written after listening to Van Morrison's Astral Weeks at the age of 19,[27] although in an interview with Drum Media he recalled writing his first song: "It was an open-tuning and had four lines about catching trains. I have got a recording of it somewhere. It was called 'Catching a Train'. I wrote a lot of songs about trains early on, trains and fires, and then I moved on to water".[34]

In 1976, Kelly appeared on Debutantes, a compilation album featuring various Melbourne-based artists, and joined pub-rockers The High Rise Bombers from 1977 to 1978.[31][35] The High Rise Bombers included Kelly (vocals, guitar, songwriter), Martin Armiger (guitar, vocals, songwriter), Lee Cass (bass guitar), Chris Dyson (guitar), Sally Ford (saxophone, songwriter), John Lloyd (drums), and Keith Shadwick (saxophone).[36] Chris Langman (guitar, vocals) replaced Dyson in early 1978. [Langman never played with the High Rise Bombers and is incorrectly listed as a guitarist on the Melbourne Club album]. In August, after Armiger left for The Sports and Ford for the Kevins, Kelly formed Paul Kelly and the Dots with Langman and Lloyd.[31] The High Rise Bombers recorded two tracks, "She's Got It" and "Domestic Criminal", which appeared on The Melbourne Club, a 1981 compilation by various artists on Missing Link Records.[31]

Kelly had already established himself as a respected songwriter—other Melbourne musicians would go to see him on their nights off.[37] Richard Guilliatt, writing for The Monthly, later described Kelly from a 1979 performance at Richmond's Kingston Hotel, the singer was "a skinny guy with a head of black curls framing a pale face and a bent nose... singing with his eyes closed, one arm outstretched and the other resting on the body of the Fender Telecaster".[38] Kelly was introduced to Hilary Brown at one of the Dots' gigs and they later married – the relationship is described in "When I First Met Your Ma" (1992).[39][40] Brown's father supplied Kelly with a gravy recipe – used on "How to Make Gravy" (1996).[41] Their son, Declan, was born in 1980.[39][40]

The Dots included various line-ups from 1978 to 1982.[42] The band released their debut single "Recognition" in 1979, which did not reach the Australian Kent Music Report Singles Chart top 50.[31][43] The Dots then signed to Mushroom Records, and at the record company's insistence, were renamed Paul Kelly and the Dots. They issued "Billy Baxter" in November 1980, which peaked at No. 38.[31][43] Rock music historian, Ian McFarlane described the single as a "delightful, ska-tinged" track.[31] Kelly's first television performance was "Billy Baxter" on the national pop show Countdown.[44] Their debut album, Talk, followed in March 1981, which reached No. 44 on the Kent Music Report Albums Chart.[43] Late in 1981 Paul Kelly and the Dots recorded their second album, Manila, in the Philippines' capital. It was issued in August 1982, but had no chart success.[31] Release was delayed by line-up changes and because Kelly was assaulted in Melbourne – he had his jaw broken.[31][45]

In an October 1982 interview with The Australian Women's Weekly, Kelly indicated he was more pleased with Manila than Talk as "It has more unity ... with this one we didn't have people dropping into the studio to play."[46] Years later Kelly disavowed both Dots albums: "I wish I could grab the other two and put 'em in a big hole".[19][47] The 1982 film, Starstruck, was directed by Gillian Armstrong and starred Jo Kennedy.[48] Paul Kelly and the Dots supplied "Rocking Institution" for its soundtrack and Kelly added to the score.[49] Kennedy released "Body and Soul", a cover of Split Enz' "She Got Body, She Got Soul" as a shared single with "Rocking Institution".[49] Acting in a minor role in Starstruck was Kaarin Fairfax, who later became Kelly's second wife.[19][48] Kelly was without a recording contract after the Dots folded in 1982.[28]

Paul Kelly Band was formed in 1983 with Michael Armiger (Martin Armiger's younger brother, bass guitar), Chris Coyne (saxophone), Maurice Frawley (guitar) and Greg Martin (drums). By 1984 Michael Barclay (ex-the Zimmermen) replaced Martin on drums and Graham Lee (guitar, pedal steel guitar) joined.[31][50] Kelly's involvement in the Melbourne drug culture—he described his heroin addiction as "a long period of occasional use"—resulted in erratic performances.[45] Problems with his marriage and drug use disrupted his career, and by 1984 the marriage had broken up. Hilary had moved to Sydney, initially leaving their young son with Kelly.[51] He disbanded the group three months later and relocated to Sydney so he could share parenting responsibilities with Hilary while Declan grew up.[15][52]

1985–1991: Coloured Girls to Messengers

editLong Bay Gaol, Christmas Eve, 1985

Paul Kelly stayed with Don Walker (Cold Chisel) in Kings Cross – Walker had lived with Hilary's sister – and wrote new songs on Walker's piano.[53] Kelly then moved into a flat with Paul Hewson (Dragon) in Elizabeth Bay.[40][54] Both Walker and Hewson encouraged Kelly to continue with his song-writing.[53] By January 1985, he recorded the self-funded album—at a cost of $3,500—Post.[10] Session musicians included Michael Barclay (Weddings Parties Anything) on harmonies, guitarist Steve Connolly (the Zimmermen), and bass guitarist Ian Rilen (Rose Tattoo, X).[28][55] They spent two weeks recording at Clive Shakespeare's studio. Shakespeare engineered the album and co-produced with Kelly. It was released in May 1985 on the independent label White Records, and licensed to Mushroom Records.[28][47]

Kelly dedicated Post to his former flatmate, Hewson, who had died of a heroin overdose in January.[56][57] According to McFarlane: "[it's] a stark, highly personalised collection of acoustic songs that showcased the extraordinary breadth of Kelly's songwriting skills."[31] Rolling Stone (Australia) hailed Post as the best record of 1985.[10][15] AllMusic's Mike DeGagne felt "While he focuses on life's daily tragedies and tribulations, there is a missing element in the music, as it lacks any vigor or flash".[58] A single, "From St Kilda to Kings Cross", was released from the album, but did not chart.[31] Russell Crowe, during his first trip to the US, visited the tourist venue of Death Valley and used Post to refocus himself: "[his] concise insights and acerbic wisdom are exactly the music for strolling the bottom of ancient oceans, both literal and metaphoric".[47] After recording Post, Kelly established a full-time band, which included Armiger, Barclay, and Connolly, bass guitarist Jon Schofield, and keyboardist Peter Bull.[59]

Paul Kelly and the Coloured Girls were named through a joke based on Lou Reed's song "Walk on the Wild Side".[31][47] Armiger soon left, and the Coloured Girls line-up stabilised in late 1985 as Barclay, Bull, Connolly, and Schofield.[31][35] Stuart Coupe, Kelly's manager, advised him to sign with Regular Records due to difficulty re-signing with Mushroom's Michael Gudinski.[47] Michelle Higgins, Mushroom's public relations officer, was a Kelly supporter and locked herself into a Sebel Townhouse Hotel room—at Mushroom's expense—for nearly a week in mid-1986, and refused to leave until Gudinski had signed Kelly to a two-album recording contract.[47][60] Kelly performed for The Rock Party, a charity project initiated by The National Campaign Against Drug Abuse, which included other Australasian musicians. The Rock Party released a 12" single, "Everything to Live For", which was produced by Joe Wissert, Phil Rigger, and Phil Beazley.[61][62]

In September, Paul Kelly and the Coloured Girls released a 24-track double LP, Gossip.[35] The album included remakes of four songs from Post, and also featured "Maralinga (Rainy Land)", a song about the effects of British nuclear tests on the Maralinga Tjarutja (indigenous people of Maralinga, South Australia).[19][33] Gossip peaked at No. 15, with singles chart success for "Before Too Long" which peaked at No. 15, and "Darling It Hurts" which reached No. 25.[43] A single LP version of Gossip featuring 15 songs was issued in the United States by A&M Records in July 1987.[35] DeGagne noted that "[it] bursts at the seams with blustery, distinguished tunes captivating both the somberness and the intrigue thrown forward from this fine Australian storyteller".[63]

Gossip was co-produced by Kelly and Alan Thorne (Hoodoo Gurus, The Stems) who, according to music journalist Robert Forster (former The Go-Betweens singer-songwriter), helped the band create "a sound that will not only influence future roots-rock bands but, through its directness, sparkle and dedication to the song, will also come to be seen as particularly Australian. Ultimately, it means the records these people made together are timeless".[64] Due to possible racist connotations, the band changed its name for international releases to Paul Kelly and the Messengers.[31][47] They made a US tour, initially supporting Crowded House and then headlining, travelling across the US by bus.[31] "Darling It Hurts" peaked at No. 19 on the Billboard Mainstream Rock chart in 1987.[65] The New York Times rock critic Jon Pareles wrote "Mr. Kelly sang one smart, catchy three-minute song after another – dozens of them – as the band played with no-frills directness" following the band's performance at the Bottom Line Club in New York.[66]

Paul Kelly and the Coloured Girls' second album, Under the Sun, was released in late 1987 in Australia and New Zealand, and in early 1988 in North America and Europe (under the name Paul Kelly and the Messengers).[35] On the Kent Music Report Albums Chart, it reached No. 19. The lead single "To Her Door", written by Kelly, peaked at No. 14 on the related singles chart.[43][67] Forster indicated that the song demonstrated one of Kelly's finest qualities as a songwriter which is his unforced empathy.[64] DeGagne observed a style similar to Elvis Costello and Steve Forbert, and said the album provided "acoustically bright story songs and character-based tales with unlimited substance".[68]

Another single, "Dumb Things", was released in early 1989 and attained No. 36 on the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) Singles Chart.[69] In the US, it reached No. 16 on the Billboard Modern Rock chart.[65] The song was included on the soundtrack for the 1988 Yahoo Serious film Young Einstein.[70] The video, directed by Claudia Castle, won an ARIA Award for 'Best Video'.[71][72] Kelly met Kaarin Fairfax, his second wife, in 1988 and they married in 1993.[15][73] From 1989 to 1992 Fairfax supplied backing vocals on tracks by Paul Kelly and the Messengers. In 1990, as country music artist Mary-Jo Starr, she released three singles and an album, Too Many Movies, using the Messengers and Kelly as session musicians. Michael Armiger, Connolly, and Frawley were in her backing tour band, The Drive-in Motel.[35][74] Fairfax and Kelly's two children are Madeleine and Memphis.[15]

So Much Water So Close to Home was released in 1989 by Paul Kelly and the Messengers in all markets. It peaked at No. 10 on the ARIA Albums Chart, but none of its singles reached the ARIA Top 40 Singles Chart.[69] Forster stated that, with "Everything's Turning to White", Kelly shows mastery in condensing a Raymond Carver tale of fishermen who discover a dead woman's body but continue to fish before reporting their find.[64] The same short story was used for the 2006 film, Jindabyne, for which Kelly composed the soundtrack.[75] DeGagne preferred "Everything's Turning to White" and "Sweet Guy" to the other album tracks, which "seem a little weak in the content department".[76] Kelly relocated back to Melbourne after having lived in Sydney for six years.[15][19] Another US tour was undertaken, but there was no further chart success for albums or singles released in the US market.[31]

In 1991 the band released Comedy, which peaked at No. 12 on the ARIA Albums Chart.[69] DeGagne noticed "a folk-filled tinge to each song, but the occasional quickened pace balances out these tunes rather nicely".[77] "From Little Things Big Things Grow", a seven-minute track from the album, was co-written by Kelly and Kev Carmody.[67] It highlights the Gurindji Strike and Vincent Lingiari as part of the Indigenous Australian struggle for land rights and reconciliation.[31][78] Forster indicates it has Dylanesque influences, and shows Kelly "honing the skills of a fine balladeer and storyteller".[64] A cover version that was released in May 2008 by The GetUp Mob, part of the GetUp! advocacy group, peaked at No. 4 on the ARIA singles charts.[79] This version included samples from speeches by Prime Ministers Paul Keating in 1992 and Kevin Rudd in 2008.[80] It featured vocals by Carmody and Kelly, as well as other Australian artists. Kelly collaborated with members of indigenous band Yothu Yindi to write "Treaty", which peaked at No. 11 in September 1991.[81][82]

"To Her Door" and "Treaty" were voted into the APRA Top 30 Australian songs of all time in 2001.[83] Paul Kelly and the Messengers gave their last performance in August 1991, with Kelly set to pursue a solo career.[31] He justified his decision: "We forged a style together. But I felt if we had kept going it would have got formulaic and that's why I broke it up. I wanted to try and start moving into other areas, start mixing things up".[56] Paul Kelly and the Messengers' final album, Hidden Things, was a collection of previously released B-sides, stray non-LP tracks, radio sessions, and other rarities. It was released in May 1992, and reached No. 29.[69] One track, "Rally Around the Drum", written with Archie Roach, was about an indigenous tent boxing man.[31]

1992–99: Solo career and with others

editSince 1992 Paul Kelly has had a solo career, fronted the Paul Kelly Band, and worked in occasional collaborations with other songwriters and performers.[31] In 1992 he was asked to compose songs for Funerals and Circuses, a Roger Bennett play about racial tensions in small-town Australia.[85][86] Kelly took the role of a petrol attendant when the play premiered at the Adelaide Fringe Festival that year and was directed by his wife, Fairfax.[87][88] Kelly co-wrote "Hey Boys" with Mark Seymour (Hunters & Collectors) for the soundtrack of the 1992 Australian film, Garbo; when released as a single it peaked at No. 62.[89] Kelly contributed songs and vocals to the soundtrack of the 1993 television series Seven Deadly Sins.[90]

Kelly's first post-Messengers solo release was the live double CD Live, May 1992, released in November 1992.[31] AllMusic's Brett Hartenbach noted that Kelly's band had fleshed out his songs in the studio, but he was still able to show "his vignettes of life, love, and the underbelly of both have plenty of power on their own".[91] Kelly had relocated to Los Angeles and signed with Vanguard Records to tour the US as a solo artist.[31] While in Los Angeles he produced fellow Australian Renée Geyer's album Difficult Woman (1994).[35] Kelly returned to Australia in 1993 and wrote a collection of lyrics, aptly titled Lyrics, which opens with a quote from Anton Chekhov: "I don't have what you would call a philosophy or coherent world view so I shall have to limit myself to describing how my heroes love, marry, give birth, die and speak."[92]: ii [93]

His next album Wanted Man, released in 1994, reached No. 11.[69] Kelly also composed music for the 1994 film Everynight ... Everynight, directed by Alkinos Tsilimidos. It is set in the notorious H division of Victoria's Pentridge Prison.[94][95] Kelly's next solo releases were Deeper Water in 1995 and Live at the Continental and the Esplanade in 1996.[35] Between March and May 1995 Kelly undertook a seven-week tour of North America, appearing on several dates with Liz Phair and Joe Jackson.[96]

By 1996, Paul Kelly Band members included Stephen Hadley (bass, ex-Black Sorrows), Bruce Haymes (keyboards), Peter Luscombe (drums, ex-Black Sorrows), and Shane O'Mara (guitar).[35] Spencer P. Jones (Beasts of Bourbon) was guest guitarist on some performances.[31] This line-up issued the CD-EP How to Make Gravy, with the title track earning Kelly a 'Song of the Year' nomination at the 1998 Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) Music Awards.[97] APRA's Debbie Kruger noted Kelly's "attraction to the theatrical" where the same protagonist is described in "To Her Door", "Love Never Runs on Time" (from Wanted Man) and "How to Make Gravy".[27]

In 1997, Kelly released his compilation album, Songs from the South: Paul Kelly's Greatest Hits, on Mushroom Records.[35] The 20-track album peaked at No. 2, and has achieved quadruple platinum certification, indicating sales of over 280,000.[69][98] Kelly won the ARIA Award in 1997 for 'Best Male Artist', having been previously nominated in 1993, 1995, and 1996.[71] At 20 September 1997 ceremony, he was inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame.[99] Kelly won the 'Best Male Artist' award again in 1998, and has been nominated for the same award a further seven times.[71]

Kelly's next album, Words and Music, appeared in 1998, which peaked at No. 17, and included three singles that did not reach the Top 40.[69] Andrew Ford interviewed Kelly for ABC radio's The Music Show in May. Ford found the album "very exciting, very visceral ... you can almost smell the sex". Kelly admitted that he preferred R & B music which deals with sex, love, and joy without becoming "either banal or smug". He finds such songs more difficult to write but believes he has started to do so.[100] 1998 also saw Kelly undertaking a three-week tour of Canada and the US to promote Words and Music.[101]

Smoke was released by Paul Kelly with Uncle Bill; the latter is a Melbourne bluegrass band comprising Gerry Hale on guitar, dobro, mandolin, fiddle, and vocals; Adam Gare on fiddle, mandolin, and vocals; Peter Somerville on banjo and vocals; and Stuart Speed on double bass.[31][35] The album featured a mix of old and new Kelly songs treated in classic bluegrass fashion.[31][33] "Our Sunshine", newly written, was a tribute to Ned Kelly, a famous Australian outlaw (not related). Kelly had previously recorded a Slim Dusty track with Uncle Bill, "Thanks a Lot", for the compilation Where Joy Kills Sorrow (1997).[31][102] Smoke was issued on Kelly's new label, Gawdaggie, through EMI Records in October 1999, and peaked at No. 36.[69] It won three awards from the Victorian Country Music Association: 'Best Group (Open)', 'Best Group (Victorian)', and 'Album of the Year' in 2000.[103] In September Kelly performed at the Spiegeltent at the Edinburgh Festival, as well as shows in London and Dublin.[104]

In 1999 Kelly formed the band Professor Ratbaggy with Hadley (bass guitar, backing vocals), Haymes (keyboards, organ, backing vocals) and Luscombe (drums). Kelly provided guitars and vocals for their debut album, Professor Ratbaggy, on EMI Records.[105] Songs were written jointly by all group members and their work was a more groove-oriented style compared to Kelly's usual folk or rock formula, using samples, synthesiser and percussion.[31] Kelly's second anthology of lyrics entitled Don't Start Me Talking was first published in 1999, with subsequent songs appended in the 2004 edition.[106] This second edition was added to the Victorian Certificate of Education English reading list for Year 12 (final year of secondary schooling) in 2006.[107]

2000–2009: Soundtracks and tribute albums

editDuring the 2000s Paul Kelly worked as a composer for film and TV scores and soundtracks, including Lantana (also as a member of Professor Ratbaggy), Silent Partner, and One Night the Moon in 2001, Fireflies in 2004, and Jindabyne in 2006.[108] These works have resulted in five award wins: ARIA 'Best Original Soundtrack' for Lantana (with Hadley, Haymes and O'Mara); Australian Film Institute (AFI) 'Open Craft Award', Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards 'Best Music Score', and Screen Music Award 'Best Soundtrack Album' for One Night the Moon (with Mairead Hannan, Carmody, John Romeril, Deirdre Hannan, and Alice Garner); Valladolid International Film Festival 'Best Music' award for Jindabyne; and six further nominations.[nb 1]

Kelly also acted in One Night the Moon alongside his then wife, Fairfax, and with their younger daughter Memphis.[108][119] All three sing on the soundtrack, including together for the lullaby, "One Night the Moon".[120] According to Romaine Moreton, Australian Screen Online curator, the "lullaby that the family sings, written by Paul Kelly, sets the tone of the film ... The song is used in this film as a vehicle to explore the characters' interior worlds, something very unusual for a film".[120] Kelly and Fairfax separated before the film's release.[88]

Roll on Summer was released in 2000 as a four-track EP, which peaked at No. 40 on the ARIA singles charts.[35][69] Kelly issued ...Nothing but a Dream in 2001, returning to his core singer-songwriter style.[33] It peaked at No. 7 on the albums chart,[69] and achieved gold record status.[121] The North American version of ...Nothing but a Dream added all four tracks from the Roll on Summer EP as bonus tracks.[122] Murray Bramwell appraised four Kelly-related works in Adelaide Review, "each of them indicative of the rich variety of his gift". On the album ...Nothing but a Dream, he preferred the opening track, "If I Could Start Today Again", to the radio single, "Somewhere in the City", and found the album generally to be "full of familiar Kelly riffs and trademarks". On Silent Partner Kelly's songwriting with Hale provides "some splendid instrumentals" with "a delightfully airy sound". The Lantana soundtrack showed Kelly's "confidence as a composer and his strong grasp of a wide range of musical styles". Finally, One Night the Moon included Mairead Hannan's "richly melodic Irish airs" which "beautifully counterpoint Kelly's work" and Carmody's "distinctive ballads".[123]

In March 2001 Kelly was a support act for Bob Dylan's tour of Australia.[124] Between August and November Kelly performed a series of acoustic shows in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Spain, and France (the latter supporting Ani DiFranco).[125] In 2002 he undertook a six-week tour of North America,[126][127] which was followed by a tour of the UK and Ireland later that year.[128] In 2002 and 2003 two tribute albums of Kelly's songs were released: Women at the Well featured songs performed by female artists, including Bic Runga, Jenny Morris, Renée Geyer, Magic Dirt, Rebecca Barnard (Rebecca's Empire), Christine Anu, and Kasey Chambers;[33][129] and Stories of Me, which featured fellow songwriters James Reyne, Mia Dyson, and Jeff Lang.[130] Chambers, a country music artist, sees Kelly as a role model: "He's the perfect example of the storyteller that I would love to be".[131] In 2003 Kelly undertook a tour of North America, the UK, and Ireland, performing at the Edmonton International Fringe Festival and again at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.[132][133]

Ways & Means was issued in 2004 and peaked at No. 13.[69] Though identified as a solo record, it was more of a group effort, with a backing band, later dubbed the Boon Companions, co-writing most of the tracks. The Boon Companions consisted of Kelly's nephew Dan Kelly on guitar, Peter Luscombe on drums, his brother Dan Luscombe on guitar and keyboards, and Bill McDonald on bass guitar.[35][134] Bramwell was impressed with their live performance in May: "Kelly steers and shapes not only his music, but the way he presents it. A live show is never just knocked together ... the details are always careful".[134] In February ABC Television started broadcasting the series Fireflies, which featured a score by Kelly and Stephen Rae.[135] The associated soundtrack CD, Fireflies: Songs of Paul Kelly, included tracks by Kelly, Paul Kelly and the Boon Companions, Professor Ratbaggy, and Paul Kelly with Uncle Bill.[136] Sian Prior sang with the Boon Companions on the Fireflies track "Los Cucumbros", which later appeared on Stardust Five.[137][138] Prior, an opera singer, became Kelly's girlfriend in 2002.[19][139] They met when she interviewed him for Sunday Arts on ABC Radio. Prior is also a journalist and university lecturer.[19][139]

In March 2004 Kelly performed across North America, including New York, Boston, Chicago, Seattle, and Los Angeles.[140] This was followed by a more extensive series of shows between July and September throughout North America and Europe.[141] In December, in Melbourne, Kelly performed 100 of his songs in alphabetical order over two nights.[142] A similar set of shows were performed in a studio at Sydney Opera House in December 2006, these and similar sets became known as his A to Z shows.[143][144] Foggy Highway was a second bluegrass-oriented album for Kelly, credited to Paul Kelly and the Stormwater Boys and issued in 2005. It peaked at No. 23 on the ARIA albums charts.[69] The line-up for the majority of the tracks was Kelly, Mick Albeck (fiddle), James Gillard (bass guitar), Rod McCormack (guitar), Ian Simpson (banjo), and Trev Warner (mandolin).[145] As with Smoke (his previous bluegrass release), Foggy Highway consisted of a mix of new compositions and rearranged Kelly classics. The Canadian edition of the release included a four-song bonus EP of out-takes.[146]

In June 2005 Kelly put together Timor Leste – Freedom Rising, a collaboration of Australian artists donating new recordings, unreleased tracks, and b-sides to make connections between a wide range of music to raise money for environmental, health, and education projects in East Timor (Timor-Leste).[147] Funds raised from the album went to Life, Love and Health and The Alola Foundation.[148][149] On 26 March 2006 Kelly performed at the Commonwealth Games closing ceremony in Melbourne, singing "Leaps and Bounds" and "Rally Around the Drum".[150][151] On 8 October Paul Kelly and the Boon Companions, Hoodoo Gurus, and Sime Nugent performed at the Athenaeum Theatre in Melbourne to again raise funds for Life, Love and Health, and to help support their ongoing programs in Timor-Leste in response to the needs of the people during the humanitarian crisis.[149][152]

Kelly formed Stardust Five in 2006, with the same line-up as Paul Kelly and the Boon Companions from Ways & Means. They released their self-titled debut album in March, with each member contributing by composing the music and Kelly providing lyrics.[153] The album has backing vocals by Prior on two tracks.[154] Kelly toured North America again in 2006,[155] appearing together with The Waifs at clubs and festivals in several US states and the Canadian province of Alberta.[156][157] In November–December Kelly undertook his A-Z tour, a series of solo acoustic performances playing 100 of his songs in alphabetical order over four nights, at the Brisbane Powerhouse, Melbourne's Spiegeltent, and at the Sydney Opera House.[144][158]

In 2007 Kelly released Stolen Apples, containing songs based on religious themes; it peaked at No. 8, and achieved gold record status.[69][159] Following the album's recording, Dan Luscombe left to join The Drones. He was replaced by Ashley Naylor (Even) on guitar and Cameron Bruce (The Polaroids) on keyboards.[8] A tour in support of the album saw Kelly perform the entire album plus selected hits from his catalogue. One of the last performances, on 20 September 2007 in Toowoomba, was filmed and released on DVD as Live Apples: Stolen Apples Performed Live in its Entirety Plus 16 More Songs, in April 2008.[160][161]

Kelly made his first appearance at the Big Day Out concerts across Australia in early 2008,[162] while in March he performed at the South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas.[163] Kelly released Stolen Apples in Ireland and the UK in July, and followed with a tour there in August.[164] In June The Age newspaper commemorated 50 years of Australian rock 'n' roll (the anniversary of the release of Johnny O'Keefe's "Wild One") by selecting the Top 50 Australian Albums. Kelly's albums Gossip and Post rated at No. 7 and No. 30 on the list.[165][166] Kelly was nominated as 'Best Male Artist' for "To Her Door (Live)" and Best Music DVD for Live Apples at the 2008 ARIA Awards.[71] In September he announced that he had reacquired the rights to his old catalogue, including those originally released by Mushroom Records—later bought out by Warner Bros. Records.[167]

Photo taken in December 2008

In November, as a result of the acquisition EMI released Songs from the South – Volume 2, a collection of Kelly's songs from the last decade, following on from Songs from the South – Volume 1.[168] The new compilation featured the first physical release of Kelly's song, "Shane Warne". Volume 1 and Volume 2 are available separately but also as a combined double album. EMI released a DVD, Paul Kelly – The Video Collection 1985–2008,[168][169] a collection of Kelly's home videos made over the past 23 years. Also included are several live performances.[167] Songs from the South – Volume 2 included one new song, "Thoughts in the Middle of the Night", which he described as "It's a band song, we all wrote it together. There's a poem by James Fenton, a British poet, called "The Mistake", which is probably an influence on the lyrics. It's a waking up in the middle of the night song, for anyone who's woken up at 3 am and not been able to get back to sleep".[34]

In the beginning of 2009 he supported Leonard Cohen's tour of Australia – his first return in 24 years.[170] Kelly's duet with country singer Melinda Schneider, "Still Here", won 'Vocal Collaboration of the Year' at the 2009 CMAA Country Music Awards of Australia.[171] In February, in response to hearing about the devastation to the Yarra Valley region of Victoria in Australia, Cohen and Kelly donated $200,000 to the Victorian Bushfire Appeal in support of those affected by the extensive Black Saturday bushfires that razed the area just weeks after their performance at the Rochford Winery for the A Day on the Green concert.[172] Kelly performed at the Melbourne Cricket Ground on 14 March for Sound Relief, a multi-venue rock music concert in support of victims of the bushfires.[173] The event was held simultaneously with a concert at the Sydney Cricket Ground.[173] All proceeds from the Melbourne concert went to the Red Cross Victorian Bushfire relief.[173] Also performing at the Melbourne concert were Augie March, Bliss n Eso with Paris Wells, Gabriella Cilmi, Hunters & Collectors, Jack Johnson, Chambers and Shane Nicholson with Troy Cassar-Daley, Kings of Leon, Jet, Midnight Oil, Liam Finn, Split Enz, and Wolfmother.[174]

On 13 and 14 November, radio station Triple J presented a Kelly tribute concert—marking his 30th anniversary as a solo artist—at the Forum Theatre in Melbourne, and highlighted his contribution to Australian music. The line-up included Missy Higgins, John Butler, Paul Dempsey (Something for Kate), Katy Steele (Little Birdy), Bob Evans, Ozi Batla (The Herd), Dan Kelly, Clare Bowditch, Jae Laffer (The Panics), Adalita Srsen (Magic Dirt), Dan Sultan, and Megan Washington interpreting Kelly's songs, with members of Augie March as the backing band and Ashley Naylor as musical director.[56] A recording of the concerts was released by ABC Music as a DVD and a double CD, Before Too Long, with a bonus CD featuring original songs by Kelly, on 19 February 2010.[175] Kelly's national 'More Songs from the South' tour in December 2009 included band members Vika Bull on vocals, Peter Luscombe on drums, Bill McDonald on bass guitar and backing vocals, Naylor on guitar, and Cameron Bruce on keyboards.[176][177] Kelly contributed to the national magazine, The Monthly, from 2009 to 2010.[178]

2010–2013: How to Make Gravy, Stories of Me and Spring and Fall

editPaul Kelly published his memoir, How to Make Gravy, via Penguin Books (Australia) on 22 September 2010.[179] "It's a mongrel memoir. It's a bit hard to describe at the moment. It's not traditional; it's writing around the A-Z theme – I tell stories around the song lyrics in alphabetical order. It's slow, so it will be a while coming, but I'll get there".[3] As a companion to his memoir, he issued an 8×CD box set, A – Z Recordings, with live performances from his A – Z Tours from 2004 to 2010.[144] The 105 tracks are listed alphabetically, and were typically performed over four nights. The set includes a booklet of photographs.[180] The related audio book on 16×CDs has Kelly joined by Australian actors, Cate Blanchett, Russell Crowe, Judy Davis, Hugh Jackman and Ben Mendelsohn each reading a chosen chapter.[181]

Maurice Frawley, a guitarist for Kelly in various groups who co-wrote "Look So Fine, Feel So Low" (1987), died of cancer in May 2009.[182] Kelly worked with Charlie Owen and others to create a 3×CD tribute album, Long Gone Whistle – The Songs of Maurice Frawley, which was released in August 2010.[183][184] In July that year, Kelly performed at Splendour in the Grass.[185] On 15 December 2010 he was inducted into The Age EG Awards Hall of Fame.[186][187] In April 2011 Kelly performed at the East Coast Blues & Roots Music Festival (Bluesfest), which was followed by appearances as a special guest at Dylan's concerts in Sydney and Melbourne.[188][189] Later that month, Kelly co-headlined a show with Neil Finn at Red Hill Auditorium in Perth; it was the first music concert at the new venue.[190] In May his memoir, How to Make Gravy, was short-listed for the Prime Minister's Literary Award in the non-fiction category; while in July it was co-winner of 'Biography of the Year' at the Australian Book Industry Awards – with Anh Do's The Happiest Refugee.[191][192]

On 29 September 2012 Kelly performed "How to Make Gravy" and "Leaps and Bounds" at the AFL Grand Final although most of the performance was not broadcast on Seven Network's pre-game segment.[193] Nui Te Koha of Sunday Herald Sun declared "Kelly, an integral part of Melbourne folklore and its music scene, and a noted footy tragic, deserved his place on the Grand Final stage – which has been long overdue ... broadcaster Seven's refusal to show Kelly's performance, except the last verse of 'Leaps and Bounds', was no laughing matter".[193] On 19 October that year, Kelly issued a new studio album, Spring and Fall, which debuted at No. 8.[69] It was recorded with Dan Kelly and Machine Translations' J Walker. Guest musicians include former band members Peter and Dan Luscombe, Vika and Linda Bull, and new collaborator, Laura Jean.[194][195]

Finn had earlier praised Kelly's song writing "There is something unique and powerful about the way Kelly mixes up everyday detail with the big issues of life, death, love and struggle – not a trace of pretence or fakery in there".[19]

Also in October, a biographical film, Paul Kelly: Stories of Me, directed by Ian Darling, was released.[198] Darling had worked on the project for two years and it included "insights from family, friends, musicians and music journalists, as well as Kelly himself".[198] The Australian Financial Review's Katrina Strickland described the documentary as "not a critique of his music, nor an intrusive look at his personal life" which uses a "much less linear approach to the life of a musician whose career has spanned four decades".[198] After it appeared on ABC-TV in October of the following year, Andrew P. Street of The Guardian noted it "brings an ambitious, complex young Kelly to life – making a relisten of his work essential".[199]

2013–2016: Collaborative albums

editDuring February and March 2013, Kelly and Neil Finn undertook a collaborative tour of Australia.[196][197] Their performance on 10 March at the Sydney Opera House was recorded for the live album, Goin' Your Way (8 November 2013).[196] It was issued as a 2× CD, which peaked at No. 5 on the ARIA Albums Chart;[200] and also as a DVD, which peaked at No. 1 on the related ARIA Music DVD Chart.[201] Later in March, Kelly toured New Zealand with Dan Kelly to promote Spring and Fall by playing in church venues.[202]

Goin' Your Way was the first of several collaborative albums Kelly would release in the following years. The Merri Soul Sessions was released December 2014, and features contributions from the Bull sisters, Kira Puru, Clairy Browne and Dan Sultan. The ensemble would also tour together in late 2014 and early 2015. In 2016, Kelly would release two albums: Seven Sonnets and a Song in April, which was a musical recreation of selected works by William Shakespeare; and Death's Dateless Night in October, a covers album with Charlie Owen.

2017–present: Life Is Fine and Nature

editKelly's first solo album in five years, Life Is Fine, was released in August 2017.[69] The album became his first number-one album and won him four ARIA Awards at that year's ceremony.[69][203] In November and December 2017, Kelly and his band undertook a seventeen-performance tour of thirteen metropolitan and regional Australian cities, as well as four performances in three cities in New Zealand to promote the release of Life is Fine. Supports on the tour included Steve Earle, Middle Kids, Busby Marou and The Eastern.[204][205] Kelly was also a featured artist on the 2018 Groovin' the Moo festival.

In August 2018, Kelly announced the release of a new album, Nature, in October. The album's lead single, "With the One I Love", was released on the same day.[206] He released another compilation album in November 2019, covering 1985–2019, Songs from the South: 1985-2019. In September 2019, he performed at the MCG in the pre-game show at the 2019 AFL Grand Final Day.[207]

On 5 February 2020, Kelly released a single titled, "Sleep, Australia, Sleep". The song addresses Australia's response to climate change.[208] Before the release of the single, the lyrics were published by The Sydney Morning Herald, with Kelly describing the song as "a lament in the form of a lullaby. Paradoxically, it can also be heard as a wake up call - a critique of the widespread attitude amongst humans that we are the most important life form on the planet."[209]

In September 2021, Kelly released a song inspired by Australian Rules footballer Eddie Betts and his battle with racism, titled "Every Step of the Way". On 19 November 2021, Kelly released his twenty-eighth studio album, Paul Kelly's Christmas Train.[210]

In July 2023, Kelly released a book and song titled, "Khawaja", inspired by Usman Khawaja.[211]

In November 2023, Kelly was inducted into the South Australian Music Awards Hall of Fame.[212]

Musical style and songwriting

editPaul Kelly has been acknowledged as one of Australia's best singer-songwriters.[213] His music style has ranged from bluegrass to studio-oriented dub reggae, but his core output comfortably straddles folk, rock, and country.[52][214] His lyrics capture Australia's vastness both in culture and landscape; he has chronicled life about him for over 30 years and is described as the poet laureate of Australia.[14][31] According to music writer Glenn A. Baker, his Australian-ness may be a reason Kelly has not achieved international success.[19] David Fricke from Rolling Stone calls Kelly "one of the finest songwriters I have ever heard, Australian or otherwise."[1]

Fellow songwriter Neil Finn (Crowded House) has said, "There is something unique and powerful about the way Kelly mixes up everyday detail with the big issues of life, death, love and struggle – not a trace of pretence or fakery in there".[19] Ross Clelland, writing for Rolling Stone, described Kelly: "[W]hile he was (rightly) lauded for his ability to sing of injustice without ranting, or deal with the darker sides of human nature non-judgementally, often overlooked was the fact he could write a damn fine melodic hook to go with those words".[215] Tim Freedman (The Whitlams) acknowledges Kelly, Peter Garrett (Midnight Oil), and John Schumann (Redgum) as inspiring him by "[furnishing] our suburbs with our own myths and social history".[216] However, Kelly has been quoted as saying "Song writing is mysterious to me. I still feel like a total beginner. I don't feel like I have got it nailed yet".[2][217] In 2007 Kelly donated his 'Lee Oskar' harmonica to the Sydney Powerhouse Museum. The museum's statement of significance cites Kelly's talent as a songwriter, his distinctive voice, and his harmonica playing, particularly on Live, May 1992.[213]

Kelly described his songwriting as "a scavenging art, a desperate act. For me it's a bit from here, a bit from there, fumbling around, never quite knowing what you're doing ... Song writing is like a way of feeling connected to mystery."[34] He has resisted the label of 'storyteller' and insists that his songs are not strictly autobiographical; "they come from imagining someone in a particular situation. Sometimes a sequence of events happens which makes it more a story, but other times it's just that situation".[27] Sometimes the same character is found in different songs, such as in "To Her Door", "Love Never Runs on Time", and "How to Make Gravy".[27]

Kelly has also provided songs for many other artists, tailoring them to their particular vocal range. Women at the Well (2002) had 14 female artists record his songs in tribute.[33] According to Kelly, he adapted his song "Foggy Highway" for Renée Geyer because "I admired her deep soul singing, ferocious and vulnerable ... When I heard the finished version ... the hairs rose up on the back of my neck."[218] Kelly and The Stormwater Boys recorded it in a bluegrass style as the title track for the 2005 album Foggy Highway.[219] Divinyls' lead singer Christina Amphlett recorded "Before Too Long"—she was attracted by the lyrics—she interpreted the song's narrator as being a stalker, and provided a female perspective in a darkly menacing manner à-la Fatal Attraction.[129]

Kelly has written songs with and for numerous artists, including Mick Thomas, Geyer, Kate Ceberano, Vika and Linda Bull, Nick Cave, Nick Barker, Kasey Chambers, Yothu Yindi, Archie Roach, Gyan, Monique Brumby, Kelly Willis, Missy Higgins, and Troy Cassar-Daley.[27] He has described how some songs he writes are suited to other vocal ranges. "Quite often, I'm trying to write a certain kind of song and it's more ambitious than what my voice will get to. That's how I started writing songs with other people in mind".[220] Kelly and Carmody's "From Little Things Big Things Grow" was analysed by Sydney University's Linguistics professor James R Martin. "[They] render the story as a narrative ... with the familiar Orientation, Complication, Evaluation, Resolution and Coda staging". Martin finds that Kelly and Carmody made the point that when people exert their rights with support from friends, they may defeat those with prestige.[221]

Kelly understands that co-writing with other songwriters lends power to his songs. "You often write songs with collaborators that you would never write by yourself. It's a way of dragging a song out of you that you wouldn't have come up with".[27] One of his collaborators, Linda Bull, described Kelly's process: they would start with a simple chat. "We'd just chuck ideas around and he'd pick the best bits. He'd take all the bluntness and crudeness out of it and make it beautiful; that's his magic ... It's conversations that you have everyday [sic]".[19] Forster summarised his 2009 review of Kelly's compilation, Songs from the South, with "[his songs] sound easy and approachable ... Then you think: If the songs are so simple and the ideas behind them so clear, why aren't more people writing like Paul Kelly and sounding as good as he does?"[64] In 2010 Carmody and Kelly's "From Little Things Big Things Grow" was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia Registry.[222]

Personal life

editKelly's first marriage (1980–84) was to Hilary Brown; the couple had a son, Declan, who later worked as a radio presenter on 3RRR's Against the Arctic from 2006.[15][19] As of 2007, he was a DJ around Melbourne and played the drums.[223] For Paul Kelly: Stories of Me, Declan recalled his feelings whenever he hears "When I First Met Your Ma", which describes Kelly's courtship of Hilary Brown.[199] Brown remembered "songs written especially for and about her" but also about other women, she quipped "There are too many girls out there! One for every song!"[199]

Kelly's second marriage (1993–2001) was to actress Kaarin Fairfax.[73] The Monthly's Richard Guilliatt travelled with Kelly, his band and "his new love and future wife, the diminutive" Fairfax on a section of the group's US tour prior to the release of Under the Sun.[38] The couple have two daughters, Madeleine and Memphis.[15] From 1989 to 1992, Fairfax supplied backing vocals on tracks by Paul Kelly and the Messengers. In 1990, as Mary-Jo Starr, a country music artist, Fairfax released three singles and an album called Too Many Movies. Memphis Kelly starred alongside her parents in the Rachel Perkins short film One Night the Moon (2001) for which Paul Kelly composed the score.[15][108] After the couple separated in 2001, Madeleine and Memphis stayed with Fairfax, but Kelly maintained contact with his daughters.[19] In 2010, Madeleine and Memphis formed a pop indie trio, Wishful, with Sam Humphrey; they were later joined by Harley Hamer and Caleb Williams. In March 2014, Wishful performed at the Port Fairy Folk Festival.[224]

Kelly was in a relationship with Sian Prior, a journalist, university lecturer and opera singer, from 2002 to 2011.[19][139] They met when Kelly was interviewed on her Sunday Arts ABC radio program.[19] Kelly wrote "You're 39, You're Beautiful and You're Mine" for Prior who was already 40 by the time he finished.[19] Prior has played clarinet and provided backing vocals on some of Kelly's songs, as well as with the Stardust Five.[225] She has performed live with Kelly on several occasions, including clarinet on six tracks of his A – Z Recordings boxed set.[226][227][228]

In his memoir, Kelly credited Prior with inspiring him to give up his long-term heroin addiction, "I got lucky, I met a woman who said: 'It's me or it'. She gave me the number of a counsellor ... I thought about 'it' every day for a long time. Less now".[229] The couple had separated during the making of Kelly's biopic, however the separation is not mentioned and Prior is not interviewed in the film.[198][199] According to Prior after a date in 2011, "[we] came home. He sat on the bed. 'I've decided I want to be single again,' he told her. 'Yes, I have been with other women.'"[230] The split occurred after she had filmed her interview and "after the breakup, [she] requested the footage not be used. Her presence in Kelly's life is as a footnote in the credits. It's as if she was never there."[230]

Siân Darling became Kelly's partner. They met in 2014 performing in a theatre show called Funeral. The couple continue to live and work together from their St Kilda base. Darling is an artist, activist, curator and producer and has been working on Kelly's professional management team since 2018.[citation needed] Her influence on Kelly's work is noted in the Stuart Coupe biography. Darling is the subject of several songs and has produced and directed some of Kelly's music videos: "With the One I Love", "Sleep Australia Sleep" and "When We're Both Old and Mad". Darling produced the 2020 re-issue version of Carmody's album Cannot Buy My Soul.[231]

Kelly's brother, Martin, is the father of Dan Kelly, a singer-guitarist.[232] Dan has performed with his uncle on several of Kelly's albums, including Ways and Means, as a member of Paul Kelly and the Boon Companions, and on Stolen Apples. Dan and Paul were both members of Stardust Five, which released Stardust Five.

Paul Kelly's younger sister, Mary Jo Kelly, is a Melbourne-based pianist who performed with him on the track "South of Germany" for Paul Kelly Live at the Athenaeum, May 1992 (1992).[137] She has performed in Latin bands and worked as a music teacher at the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School.[19][20] Mary Jo provided piano on Archie Roach's album Charcoal Lane (1990), which was produced by Kelly and Connolly.[233][234]

Awards and recognition

editPaul Kelly has won several awards, including 17 ARIA Awards from the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA), and five APRA Awards from either the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) alone or together with the Australian Guild of Screen Composers. APRA named "To Her Door", solely written by Kelly,[67] and "Treaty", written by Kelly and members of Yothu Yindi,[82] in their Top 30 best Australian songs of all time in 2001.[83] Kelly was inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame in 1997, alongside the Bee Gees and Graeme Bell.[71][99] He has won six Country Music Awards from the Country Music Association of Australia,[235][236] and four Mo Awards (Australian entertainment industry).[237][238] Kelly was a Victorian State Finalist for the 2012 Australian of the Year Award.[239] Kelly was appointed as an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2017 for distinguished service to the performing arts and to the promotion of the national identity through contributions as a singer, songwriter and musician.[4]

In August 2022, the City of Adelaide renamed a laneway in the city centre off Flinders Street Paul Kelly Lane. Previously named Pilgrim Lane after the adjacent Pilgrim Uniting Church, the lane is now called Paul Kelly Lane. It is the fourth such renaming after musicians associated with the city, the others being Sia Furler, No Fixed Address, and Cold Chisel.[240]

Bibliography

editPaul Kelly has written, co-written or edited the following:[85][241]

- Kelly, Paul; Paine, Richard (1990). Songs [musical score]. Sydney: Wise. ISBN 978-0-949785-27-5.

- Kelly, Paul; Paine, Richard (1993). Songs. Book two [musical score]. Sydney: Wise. ISBN 978-0-949785-31-2.

- Kelly, Paul (29 September 1993). Lyrics. Pymble, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 978-0-207-18221-1.

- Bennett, Roger (1995). Funerals and circuses. Songs by Paul Kelly. Sydney: Currency Press. ISBN 978-0-86819-380-9.

- Kelly, Paul (2004) [1999]. Don't start me talking: lyrics 1984–2004 (2nd ed.). St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-105-2.

- Kelly, Paul; Judith, Kate; National Educational Advancement Programs (2005). Don't start me talking: lyrics 1984–2004. Carlton, Victoria: National Educational Advancement Programs (NEAP). ISBN 978-1-86478-099-4.

- Kelly, Paul; Carmody, Kev (1 December 2008). From Little Things Big Things Grow. Illustrators: Peter Hudson, Kalkarinji School Children Northern Territory. Camberwell East, Victoria: One Day Hill. ISBN 978-0-9805643-1-0.

- Kelly, Paul (21 September 2010). How to Make Gravy. Camberwell, Vic: Penguin Books (Australia). ISBN 978-1-926428-22-2.

- Kelly, Paul (19 November 2019). Love Is Strong As Death: Poems Chosen by Paul Kelly. Camberwell, Vic: Penguin Books (Australia). ISBN 978-1-760892-68-5.

Discography

editStudio albums

- Talk (with the Dots) (1981)

- Manila (with the Dots) (1982)

- Post (1985)

- Gossip (with the Coloured Girls) (1986)

- Under the Sun (with the Coloured Girls) (1987)

- So Much Water So Close to Home (with the Messengers) (1989)

- Comedy (with The Messengers) (1991)

- Hidden Things (with The Messengers) (1992)

- Wanted Man (1994)

- Deeper Water (1995)

- Words and Music (1998)

- Smoke (with Uncle Bill) (1999)

- Professor Ratbaggy (with Professor Ratbaggy) (1999)

- ...Nothing but a Dream (2001)

- Ways & Means (2004)

- Foggy Highway (with The Stormwater Boys) (2005)

- Stardust Five (with Stardust Five) (2006)

- Stolen Apples (2007)

- Spring and Fall (2012)

- The Merri Soul Sessions (with Vika and Linda Bull, Dan Sultan, Kira Puru and Clairy Browne) (2014)

- Seven Sonnets and a Song (2016)

- Death's Dateless Night (with Charlie Owen) (2016)

- Life Is Fine (2017)

- Nature (2018)

- Thirteen Ways to Look at Birds (with James Ledger, Alice Keath, and Seraphim Trio) (2019)

- Forty Days (2020)

- Please Leave Your Light On[242] (with Paul Grabowsky) (2020)

- Paul Kelly's Christmas Train (2021)

- Fever Longing Still (2024)

Films

editPaul Kelly: Stories of Me (1 October 2012) is an Australian documentary by Shark Island Productions.[198] The film is an intimate portrait of Kelly that follows his 40-year career as Australia's foremost singer-songwriter.[198] The film won the Film Critics Circle Award in 2012 for Best Documentary, and the ASE Award in 2013 for Best Documentary Editing. Nominations include the ADG Award in 2013 for Best Documentary Feature and AACTA Award 2013 for Best Sound in a Documentary. The film was part of the Official Selection at the Melbourne International Film Festival 2012[243] and the Canberra International Film Festival in that year.[244]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Award wins mentioned here are:

- Lantana award win for 'Best Original Soundtrack' at the ARIA Music Awards of 2002.[71][109] The award is shared with fellow composers and performers, Stephen Hadley, Bruce Haymes, Peter Luscombe and Shane O'Mara.[110] All were members of Paul Kelly Band and, except for O'Mara, were also members of Professor Ratbaggy.[35][105]

- One Night the Moon award win for 'Open Craft Award' at the Australian Film Institute (AFI) Awards in 2001.[111] The award is shared with fellow composers and performers Mairead Hannan and Kev Carmody.[111]

- One Night the Moon award win for 'Best Soundtrack Album' at the APRA Awards of 2002, Screen Music Awards presented by Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) and Australian Guild of Screen Composers.[112][113] The award is shared with fellow composers and performers, Mairead Hannan, Carmody, John Romeril, Deirdre Hannan, Alice Garner.[112][114]

- One Night the Moon award win for 'Best Music Score' at the Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards of 2002. The award is shared with Mairead Hannan and Carmody.[115][116]

- Jindabyne award win for 'Best Music' at Valladolid International Film Festival in 2006.[117] The award is shared with composer and performer Dan Luscombe, who was a member of Paul Kelly Band.[117][118]

References

edit- General

- Doyle, Brian (25 January 2004). "Chapter Ten: Deeper Water". Spirited Men: Story, Soul & Substance. Cambridge, Mass. pp. 113–127. ISBN 978-1-56101-258-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kelly, Paul (21 September 2010). How to Make Gravy. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Books (Australia). ISBN 978-1-926428-22-2.

- Leser, David (1999). "Paul Kelly – June 1991" (PDF). The Whites of Their Eyes: Profiles. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. pp. 203–211. ISBN 978-1-86508-114-4. Retrieved 2 December 2017. Note: Original profile was published as "Paul Kelly" in Good Weekend, The Sydney Morning Herald, on 2 June 1991.ISSN 0312-6315. OCLC 226369741.

- McFarlane, Ian (1999). Encyclopedia of Australian Rock and Pop. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-072-7. Archived from the original on 10 October 2004. Retrieved 23 July 2011. Note: Archived copy at WHAMMO (Worldwide Home of Australasian Music and More Online) homepage of Encyclopedia of Australian Rock and Pop.

- Nimmervoll, Ed. "Paul Kelly > Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- Spencer, Chris; Nowara, Zbig; McHenry, Paul (2002) [1987]. The Who's Who of Australian Rock. notes by Ed Nimmervoll. Noble Park, Victoria: Five Mile Press. ISBN 978-1-86503-891-9.[245]

- Specific

- ^ a b David, Fricke (1997). Songs from the South: Paul Kelly's Greatest Hits (Media notes). Paul Kelly. Mushroom Records. p. 2. MUSH33009.2.

- ^ a b "Paul Kelly Biography". Dumbthings. Paul Kelly Official Website (Eva Zsigri). June 1997. Archived from the original on 14 April 1999. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ a b Donovan, Patrick (15 May 2009). "Wanted Man". The Age. ISSN 0312-6307. OCLC 224060909. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Officer (AO) in the General Division of the Order of Australia" (PDF). Australia Day 2017 Honours List. Governor-General of Australia. 26 January 2017. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Sargent, S. (2016). Indigenous Rights: Changes and Challenges in the 21st Century. Legend Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-78955-131-0. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Doyle, p. 115.

- ^ "Paul Kelly Biography". Music Australia. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Paul Kelly Interview". Rip It Up Magazine. No. 992. 17–23 July 2006. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Kelly (2010), pp. 190–193.

- ^ a b c McMahon, Bruce (7 July 2007). "Paul Kelly Has no Answers". The Courier-Mail. ISSN 1322-5235. OCLC 223420922. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ a b Doyle, p. 116.

- ^ "Our History". Kelly & Co. Lawyers. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Kelly (2010), p. 223.

- ^ a b c Denton, Andrew (5 July 2004). "Paul Kelly: Transcripts". Enough Rope with Andrew Denton. Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wilkie, Meredith (25 April 2004). "Lure of Hearth and Home". The Age. ISSN 0312-6307. OCLC 224060909. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Kelly (2010), p 10.

- ^ a b Leser, p. 204.

- ^ "Italian Historical Society – Fact Sheet – The Arts" (PDF). CO.AS.IT. 2006. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Horsburgh, Susan (4 June 2007). "Song Lines". The Sydney Morning Herald. ISSN 0312-6315. OCLC 226369741. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Music Curriculum – VCASS". Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School (VCASS). Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Higgins-Devine, Kelly; Hayes, Rita (10 June 2004). "A Letter from Sister Rita". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Radio Queensland. Archived from the original on 28 January 2005. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "Edmund Rice Volunteer Scheme". Edmund Rice Oceania. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "Paul Kelly on his new version of How to Make Gravy: 'Christmas music gets a bad rap'". The Guardian. 20 December 2021.

- ^ Bunworth, Mick (10 October 2001). "Ballarat – The Australian Political Barometer". The 7.30 Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Television. Archived from the original on 25 February 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "Greens' Ballarat Candidate to Decide on Preferences". The 7.30 Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Television. 10 November 2003. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Kelly (2010), pp. 208–214.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kruger, Debbie (December 2002). "Paul Kelly: Words Are Never Enough". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA). Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Blanda, Eva (June 1997). "Paul Kelly Australian Singer-songwriter: White Records Release". Other People's Houses. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Magner, Brigid. "Don't Start Me Talking : Lyrics 1984–2004" (PDF). Insight Publications. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2006.

- ^ Doyle, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad McFarlane. "'Paul Kelly' entry". Archived from the original on 30 September 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Kelly (2010), pp. 16–18.

- ^ a b c d e f Nimmervoll, Ed. "Paul Kelly". Howlspace. White Room Electronic Publishing Pty Ltd (Tom Denison). Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Jenkins, Jeff (8 November 2008). "From Little Things Big Things Grow". Drum Media (Perth). No. 110. Craig Treweek, Leigh Treweek. pp. 15–17. (Libraries Australia ID 47647122[permanent dead link]).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Holmgren, Magnus. "Paul Kelly". Australian Rock Database (Passagen). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Spencer et al, (2002), High Rise Bombers entry.

- ^ Nimmervoll. AllMusic.

- ^ a b Guilliatt, Richard (April 2013). "Paul Kelly's Wild Years". The Monthly (88). Schwartz Publishing (Black Inc). ISSN 1832-3421. OCLC 427307841. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b Kelly (2010), p. 80, 281–282, 477–480.

- ^ a b c "Paul Kelly Reveals the Stories Behind the Songs". The Sydney Morning Herald. 24 September 2010. ISSN 0312-6315. OCLC 226369741. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Kelly (2010), p. 206.

- ^ Spencer et al, (2002), Kelly, Paul and the Dots entry.

- ^ a b c d e Kent, David (March 1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, New South Wales: Australian Chart Book Ltd. ISBN 978-0-646-11917-5. Note: Used for Australian Singles and Albums charting from 1974 until Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) created their own charts in mid-1988. In 1992, Kent back calculated chart positions for 1970–1974. Entries under Artist names: Kelly, Paul; Kelly, Paul and the Dots; Kelly, Paul and the Coloured Girls; Kelly, Paul and the Messengers.

- ^ Carney, Shaun (July 1994). "Kelly Country". Rolling Stone. No. 498. ACP Magazines. OCLC 259372869. Archived from the original on 8 February 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b Leser, p. 206.

- ^ Moore, Susan (6 October 1982). "Moore on Pop". The Australian Women's Weekly. National Library of Australia. p. 154. ISSN 0005-0458. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jenkins, Jeff; Meldrum, Ian (15 October 2007). "31: Paul Kelly – From Little Things Big Things Grow". Molly Meldrum Presents 50 Years of Rock in Australia. Melbourne: Wilkinson Publishing. pp. 213–219. ISBN 978-1-921332-11-1.

- ^ a b "Starstruck: Cast & Details". TV Guide. OpenGate Capital. ISSN 0039-8543. OCLC 10602653. Archived from the original on 10 August 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b Nicholson, Dennis Way (2007) [1997]. "Star Struck". Australian Soundtrack Recordings. Sydney: Australian Music Centre (Nodette Enterprises Pty Ltd). ISBN 978-0-646-31753-3. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Spencer et al, (2002), Kelly, Paul Band entry.

- ^ Kelly (2010), p. 35.

- ^ a b Kelly, Paul; Judith, Kate; National Educational Advancement Programs (2005). Don't Start Me Talking: Lyrics 1984–2004 – Smartstudy English guide. Carlton, Victoria: National Educational Advancement Programs (NEAP). pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1-86478-099-4.

- ^ a b Kelly (2010), pp. 182–184.

- ^ Leser, p. 207.

- ^ Holmgren, Magnus. "The Zimmermen". Australian Rock Database (Passagen). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Sawrey, Kaitlyn (November 2009). "Ausmusic Month 2009 – Celebrating Australian Music All Through November 2009". Triple J. Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Nimmervoll, Ed. "Dragon". Howlspace. White Room Electronic Publishing Pty Ltd. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "Post – Paul Kelly & The Messengers – Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Spencer et al, (2002), Kelly, Paul and the Coloured Girls entry.

- ^ "Songs from the South: The Best of Paul Kelly". Amazon. 13 May 1997. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "'Everything to Live For' – The Rock Party". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Holmgren, Magnus; Warnqvist, Stefan. "The Rock Party". Australian Rock Database (Passagen). Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "Gossip – Paul Kelly & The Messengers – Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Forster, Robert (April 2009). "Thoughts in the Middle of a Career: Paul Kelly's – Songs from the South". The Monthly. 44. Schwartz Publishing (Black Inc): 62–64. ISSN 1832-3421. OCLC 427307841. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Paul Kelly | Charts & Awards | Billboard Singles". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (18 September 1988). "Two Rock Storytellers Hit Their Stride". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "'To Her Door' at APRA Search Engine". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA). Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "Under the Sun – Paul Kelly & The Messengers – Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Discography Paul Kelly". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2017. Note: based on information supplied by ARIA.

- ^ Holmgren, Magnus. "Young Einstein (Soundtrack)". Australian Rock Database (Passagen). Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Winners by Year – 27th ARIA Awards 2013: Search Results 'Paul Kelly'". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Winners by Year: 1988". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ a b Mordue, Mark (12 January 1996). "Poet of the Common Man". The Sydney Morning Herald. ISSN 0312-6315. OCLC 226369741. Archived from the original on 13 November 1999. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Holmgren, Magnus. "Maurice Frawley". Australian Rock Database (Passagen). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "Jindabyne Production Credits – Bios – Paul Kelly Composer". Sony Films. 27 April 2007. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "So Much Water, So Close to Home – Paul Kelly and The Messenger – Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "Comedy – Paul Kelly & The Messengers – Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Negus, George (5 July 2004). "GNT History – Transcripts: 'The Gurindji Strike'". George Negus Tonight. Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Television. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "The GetUp Mob – 'From Little Things Big Things Grow' (Song)". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Morgan, Clare (29 April 2008). "Rudd, Keating and Crew Storm Pop Charts". The Sydney Morning Herald. ISSN 0312-6315. OCLC 226369741. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "Yothu Yindi – 'Treaty' (Song)". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b "ASCAP ACE Search Results for 'Kelly Paul Maurice'". American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b Kruger, Debbie (2 May 2001). "The Songs that Resonate Through the Years – Industry Votes for Top 30 Australian Songs" (PDF). Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA). pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Blanda, Eva (October 2003). "The Recordings of Paul Kelly as a Solo Artist". Other People's Houses Australian Music Web Site. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Funerals and Circuses". Catalogue. National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "Roger Bennett: Playwright". The Playwrights Database (Julian Oddy). Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "Indigenous Theatre: The Future in Black and White" (PDF). Theatre. Australia Council. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b Lavelle, Cath, ed. (November 2001). "One Night the Moon Media Kit" (PDF). Surry Hills, New South Wales: MusicArtsDance Films. pp. 1, 4–5, 7–10, 13–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ Nicholson, Dennis Way (2007) [1997]. "Garbo: The Soundtrack from the Movie Starring Los Trios Ringbarkus". Australian Soundtrack Recordings. Sydney: Australian Music Centre (Nodette Enterprises Pty Ltd). ISBN 978-0-646-31753-3. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Nicholson, Dennis Way (2007) [1997]. "Seven Deadly Sins Soundtrack: Music from the ABC TV Series". Australian Soundtrack Recordings. Sydney: Australian Music Centre (Nodette Enterprises Pty Ltd). ISBN 978-0-646-31753-3. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Hartenbach, Brett. "Live, May 1992 – Paul Kelly – Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Kelly, Paul (2004) [1999]. Don't Start Me Talking: Lyrics 1984–2004 (2nd ed.). St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. pp. 103, 10, ii. ISBN 978-1-86508-105-2.

- ^ Kelly (2010), p. 465.

- ^ Mooney, Ray; Tsilimidos, Alkinos; Kelly, Paul; O'Mara, Shane; Field, David; Hunter, Bill (1994). "Everynight – Everynight". Libraries Australia. National Library of Australia. Archived from the original (VHS) on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "Title Details – Everynight... Everynight". National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA). Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "Paul Kelly Past Tour Dates (March – May 1995)". Dumbthings. Official Website of Paul Kelly. Archived from the original on 29 January 2005. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "1998 Music Awards Nominations". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA). Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2006 Albums". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b "ARIA 2008 Hall of Fame Inductees Listing". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2011.