Herpes simplex virus 1 (cold sores) and 2 (genital herpes) (HSV-1 and HSV-2), also known by their taxonomic names Human alphaherpesvirus 1 and Human alphaherpesvirus 2, are two members of the human Herpesviridae family, a set of viruses that produce viral infections in the majority of humans.[1][2] Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 are very common and contagious. They can be spread when an infected person begins shedding the virus.

| Herpes simplex viruses | |

|---|---|

| |

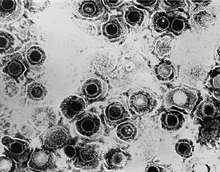

| TEM micrograph of virions of a herpes simplex virus species | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Duplodnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Heunggongvirae |

| Phylum: | Peploviricota |

| Class: | Herviviricetes |

| Order: | Herpesvirales |

| Family: | Orthoherpesviridae |

| Subfamily: | Alphaherpesvirinae |

| Genus: | Simplexvirus |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

|

All other Simplexvirus sp.:

| |

As of 2016, about 67% of the world population under the age of 50 had HSV-1.[3] In the United States, about 47.8% and 11.9% are estimated to have HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively, though actual prevalence may be much higher.[4] Because it can be transmitted through any intimate contact, it is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections.[5]

Symptoms

editMany of those who are infected never develop symptoms.[6] Symptoms, when they occur, may include watery blisters in the skin of any location of the body, or in mucous membranes of the mouth, lips, nose, genitals,[1] or eyes (herpes simplex keratitis).[7] Lesions heal with a scab characteristic of herpetic disease. Sometimes, the viruses cause mild or atypical symptoms during outbreaks. However, they can also cause more troublesome forms of herpes simplex. As neurotropic and neuroinvasive viruses, HSV-1 and -2 persist in the body by hiding from the immune system in the cell bodies of neurons, particularly in sensory ganglia. After the initial or primary infection, some infected people experience sporadic episodes of viral reactivation or outbreaks. In an outbreak, the virus in a nerve cell becomes active and is transported via the neuron's axon to the skin, where virus replication and shedding occur and may cause new sores.[8]

Transmission

editHSV-1 and HSV-2 are transmitted by contact with an infected person who has reactivations of the virus. HSV 1 and HSV-2 are periodically shed, most often asymptomatically. [citation needed]

In a study of people with first-episode genital HSV-1 infection from 2022, genital shedding of HSV-1 was detected on 12% of days at 2 months and declined significantly to 7% of days at 11 months. Most genital shedding was asymptomatic; genital and oral lesions and oral shedding were rare.[9]

Most sexual transmissions of HSV-2 occur during periods of asymptomatic shedding.[10] Asymptomatic reactivation means that the virus causes atypical, subtle, or hard-to-notice symptoms that are not identified as an active herpes infection, so acquiring the virus is possible even if no active HSV blisters or sores are present. In one study, daily genital swab samples detected HSV-2 at a median of 12–28% of days among those who had an outbreak, and 10% of days among those with asymptomatic infection (no prior outbreaks), with many of these episodes occurring without visible outbreak ("subclinical shedding").[11]

In another study, 73 subjects were randomized to receive valaciclovir 1 g daily or placebo for 60 days each in a two-way crossover design. A daily swab of the genital area was self-collected for HSV-2 detection by polymerase chain reaction, to compare the effect of valaciclovir versus placebo on asymptomatic viral shedding in immunocompetent, HSV-2 seropositive subjects without a history of symptomatic genital herpes infection. The study found that valaciclovir significantly reduced shedding during subclinical days compared to placebo, showing a 71% reduction; 84% of subjects had no shedding while receiving valaciclovir versus 54% of subjects on placebo. About 88% of patients treated with valaciclovir had no recognized signs or symptoms versus 77% for placebo.[12]

For HSV-2, subclinical shedding may account for most of the transmission.[11] Studies on discordant partners (one infected with HSV-2, one not) show that the transmission rate is approximately 5–8.9 per 10,000 sexual contacts, with condom usage greatly reducing the risk of acquisition.[13] Atypical symptoms are often attributed to other causes, such as a yeast infection.[14][15] HSV-1 is often acquired orally during childhood. It may also be sexually transmitted, including contact with saliva, such as kissing and oral sex.[16] Historically HSV-2 was primarily a sexually transmitted infection, but rates of HSV-1 genital infections have been increasing for the last few decades.[14]

Both viruses may also be transmitted vertically during natural childbirth.[17][18] However, the risk of transmission is minimal if the mother has no symptoms nor exposed blisters during delivery. The risk is considerable when the mother is infected with the virus for the first time during late pregnancy, reflecting high viral load.[19] While most viral STDs can not be transmitted through objects as the virus dies quickly outside of the body, HSV can survive for up to 4.5 hours on surfaces and can be transmitted through use of towels, toothbrushes, cups, cutlery, etc.[20][21][22][23]

Herpes simplex viruses can affect areas of skin exposed to contact with an infected person. An example of this is herpetic whitlow, which is a herpes infection on the fingers; it was commonly found on dental surgeon's hands prior to the routine use of gloves when treating patients. Shaking hands with an infected person does not transmit this disease.[24] Genital infection of HSV-2 increases the risk of acquiring HIV.[25]

Virology

editHSV has been a model virus for many studies in molecular biology. For instance, one of the first functional promoters in eukaryotes was discovered in HSV (of the thymidine kinase gene) and the virion protein VP16 is one of the most-studied transcriptional activators.[26]

Viral structure

editAnimal herpes viruses all share some common properties. The structure of herpes viruses consists of a relatively large, double-stranded, linear DNA genome encased within an icosahedral protein cage called the capsid, which is wrapped in a lipid bilayer called the envelope. The envelope is joined to the capsid by means of a tegument. This complete particle is known as the virion.[27] HSV-1 and HSV-2 each contain at least 74 genes (or open reading frames, ORFs) within their genomes,[28] although speculation over gene crowding allows as many as 84 unique protein coding genes by 94 putative ORFs.[29] These genes encode a variety of proteins involved in forming the capsid, tegument and envelope of the virus, as well as controlling the replication and infectivity of the virus. These genes and their functions are summarized in the table below.[citation needed]

The genomes of HSV-1 and HSV-2 are complex and contain two unique regions called the long unique region (UL) and the short unique region (US). Of the 74 known ORFs, UL contains 56 viral genes, whereas US contains only 12.[28] Transcription of HSV genes is catalyzed by RNA polymerase II of the infected host.[28] Immediate early genes, which encode proteins for example ICP22[30] that regulate the expression of early and late viral genes, are the first to be expressed following infection. Early gene expression follows, to allow the synthesis of enzymes involved in DNA replication and the production of certain envelope glycoproteins. Expression of late genes occurs last; this group of genes predominantly encode proteins that form the virion particle.[28]

Five proteins from (UL) form the viral capsid - UL6, UL18, UL35, UL38, and the major capsid protein UL19.[27]

Cellular entry

editEntry of HSV into a host cell involves several glycoproteins on the surface of the enveloped virus binding to their transmembrane receptors on the cell surface. Many of these receptors are then pulled inwards by the cell, which is thought to open a ring of three gHgL heterodimers stabilizing a compact conformation of the gB glycoprotein, so that it springs out and punctures the cell membrane.[31] The envelope covering the virus particle then fuses with the cell membrane, creating a pore through which the contents of the viral envelope enters the host cell.[citation needed]

The sequential stages of HSV entry are analogous to those of other viruses. At first, complementary receptors on the virus and the cell surface bring the viral and cell membranes into proximity. Interactions of these molecules then form a stable entry pore through which the viral envelope contents are introduced to the host cell. The virus can also be endocytosed after binding to the receptors, and the fusion could occur at the endosome. In electron micrographs, the outer leaflets of the viral and cellular lipid bilayers have been seen merged;[32] this hemifusion may be on the usual path to entry or it may usually be an arrested state more likely to be captured than a transient entry mechanism.[citation needed]

In the case of a herpes virus, initial interactions occur when two viral envelope glycoprotein called glycoprotein C (gC) and glycoprotein B (gB) bind to a cell surface polysaccharide called heparan sulfate. Next, the major receptor binding protein, glycoprotein D (gD), binds specifically to at least one of three known entry receptors.[33] These cell receptors include herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), nectin-1 and 3-O sulfated heparan sulfate. The nectin receptors usually produce cell-cell adhesion, to provide a strong point of attachment for the virus to the host cell.[31] These interactions bring the membrane surfaces into mutual proximity and allow for other glycoproteins embedded in the viral envelope to interact with other cell surface molecules. Once bound to the HVEM, gD changes its conformation and interacts with viral glycoproteins H (gH) and L (gL), which form a complex. The interaction of these membrane proteins may result in a hemifusion state. gB interaction with the gH/gL complex creates an entry pore for the viral capsid.[32] gB interacts with glycosaminoglycans on the surface of the host cell. [citation needed]

Genetic inoculation

editAfter the viral capsid enters the cellular cytoplasm, it starts to express viral protein ICP27. ICP27 is a regulator protein that causes disruption in host protein synthesis and utilizes it for viral replication. ICP27 binds with a cellular enzyme Serine-Arginine Protein Kinase 1, SRPK1. Formation of this complex causes the SRPK1 shift from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, and the viral genome gets transported to the cell nucleus.[34] Once attached to the nucleus at a nuclear entry pore, the capsid ejects its DNA contents via the capsid portal. The capsid portal is formed by 12 copies of portal protein, UL6, arranged as a ring; the proteins contain a leucine zipper sequence of amino acids, which allow them to adhere to each other.[35] Each icosahedral capsid contains a single portal, located in one vertex.[36][37] The DNA exits the capsid in a single linear segment.[38]

Immune evasion

editHSV evades the immune system through interference with MHC class I antigen presentation on the cell surface, by blocking the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) induced by the secretion of ICP-47 by HSV. In the host cell, TAP transports digested viral antigen epitope peptides from the cytosol to the endoplasmic reticulum, allowing these epitopes to be combined with MHC class I molecules and presented on the surface of the cell. Viral epitope presentation with MHC class I is a requirement for activation of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs), the major effectors of the cell-mediated immune response against virally-infected cells. ICP-47 prevents initiation of a CTL-response against HSV, allowing the virus to survive for a protracted period in the host.[39] HSV usually produces cytopathic effect (CPE) within 24–72 hours post-infection in permissive cell lines which is observed by classical plaque formation. However, HSV-1 clinical isolates have also been reported that did not show any CPE in Vero and A549 cell cultures over several passages with low level of virus protein expression. Probably these HSV-1 isolates are evolving towards a more "cryptic" form to establish chronic infection thereby unravelling yet another strategy to evade the host immune system, besides neuronal latency.[40]

Replication

editFollowing infection of a cell, a cascade of herpes virus proteins, called immediate-early, early, and late, is produced. Research using flow cytometry on another member of the herpes virus family, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, indicates the possibility of an additional lytic stage, delayed-late.[41] These stages of lytic infection, particularly late lytic, are distinct from the latency stage. In the case of HSV-1, no protein products are detected during latency, whereas they are detected during the lytic cycle.[citation needed]

The early proteins transcribed are used in the regulation of genetic replication of the virus. On entering the cell, an α-TIF protein joins the viral particle and aids in immediate-early transcription. The virion host shutoff protein (VHS or UL41) is very important to viral replication.[42] This enzyme shuts off protein synthesis in the host, degrades host mRNA, helps in viral replication, and regulates gene expression of viral proteins. The viral genome immediately travels to the nucleus, but the VHS protein remains in the cytoplasm.[43][44]

The late proteins form the capsid and the receptors on the surface of the virus. Packaging of the viral particles — including the genome, core and the capsid - occurs in the nucleus of the cell. Here, concatemers of the viral genome are separated by cleavage and are placed into formed capsids. HSV-1 undergoes a process of primary and secondary envelopment. The primary envelope is acquired by budding into the inner nuclear membrane of the cell. This then fuses with the outer nuclear membrane. The virus acquires its final envelope by budding into cytoplasmic vesicles.[45]

Latent infection

editHSVs may persist in a quiescent but persistent form known as latent infection, notably in neural ganglia.[1] The HSV genome circular DNA resides in the cell nucleus as an episome.[46] HSV-1 tends to reside in the trigeminal ganglia, while HSV-2 tends to reside in the sacral ganglia, but these are historical tendencies only. During latent infection of a cell, HSVs express latency-associated transcript (LAT) RNA. LAT regulates the host cell genome and interferes with natural cell death mechanisms. By maintaining the host cells, LAT expression preserves a reservoir of the virus, which allows subsequent, usually symptomatic, periodic recurrences or "outbreaks" characteristic of nonlatency. Whether or not recurrences are symptomatic, viral shedding occurs to infect a new host.[citation needed]

A protein found in neurons may bind to herpes virus DNA and regulate latency. Herpes virus DNA contains a gene for a protein called ICP4, which is an important transactivator of genes associated with lytic infection in HSV-1.[47] Elements surrounding the gene for ICP4 bind a protein known as the human neuronal protein neuronal restrictive silencing factor (NRSF) or human repressor element silencing transcription factor (REST). When bound to the viral DNA elements, histone deacetylation occurs atop the ICP4 gene sequence to prevent initiation of transcription from this gene, thereby preventing transcription of other viral genes involved in the lytic cycle.[47][48] Another HSV protein reverses the inhibition of ICP4 protein synthesis. ICP0 dissociates NRSF from the ICP4 gene and thus prevents silencing of the viral DNA.[49]

Genome

editThe HSV genome spans about 150,000 bp and consists of two unique segments, named unique long (UL) and unique short (US), as well as terminal inverted repeats found to the two ends of them named repeat long (RL) and repeat short (RS). There are also minor "terminal redundancy" (α) elements found on the further ends of RS. The overall arrangement is RL-UL-RL-α-RS-US-RS-α with each pair of repeats inverting each other. The whole sequence is then encapsuled in a terminal direct repeat. The long and short parts each have their own origins of replication, with OriL located between UL28 and UL30 and OriS located in a pair near the RS.[50] As the L and S segments can be assembled in any direction, they can be inverted relative to each other freely, forming various linear isomers.[51]

| ORF | Protein alias | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | Function/description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat long (RL) | ||||

| ICP0/RL2 | ICP0; IE110; α0 | P08393 | P28284 | E3 ubiquitin ligase that activates viral gene transcription by opposing chromatinization of the viral genome and counteracts intrinsic- and interferon-based antiviral responses.[53] |

| RL1 | RL1; ICP34.5 | O12396 | P28283 | Neurovirulence factor. Antagonizes PKR by de-phosphorylating eIF4a. Binds to BECN1 and inactivates autophagy. |

| LAT | LRP1, LRP2 | P17588 P17589 |

Latency-associated transcript abd protein products (latency-related protein) | |

| Unique long (UL) | ||||

| UL1 | Glycoprotein L | P10185 | P28278 | Surface and membrane |

| UL2 | Uracil-DNA glycosylase | P10186 | P13158 P28275 | Uracil-DNA glycosylase |

| UL3 | UL3 | P10187 Q1XBW5 | P0C012 P28279 | unknown |

| UL4 | UL4 | P10188 | P28280 | unknown |

| UL5 | HELI | P10189 | P28277 | DNA helicase |

| UL6 | Portal protein UL-6 | P10190 | Twelve of these proteins constitute the capsid portal ring through which DNA enters and exits the capsid.[35][36][37] | |

| UL7 | Cytoplasmic envelopment protein 1 | P10191 | P89430 | Virion maturation |

| UL8 | DNA helicase/primase complex-associated protein | P10192 | P89431 | DNA virus helicase-primase complex-associated protein |

| UL9 | Replication origin-binding protein | P10193 | P89432 | Replication origin-binding protein |

| UL10 | Glycoprotein M | P04288 | P89433 | Surface and membrane |

| UL11 | Cytoplasmic envelopment protein 3 | P04289 Q68980 | P13294 | virion exit and secondary envelopment |

| UL12 | Alkaline nuclease | P04294 | P06489 | Alkaline exonuclease |

| UL13 | UL13 | P04290 | P89436 | Serine-threonine protein kinase |

| UL14 | UL14 | P04291 | P89437 | Tegument protein |

| UL15 | TRM3 | P04295 | P89438 | Processing and packaging of DNA |

| UL16 | UL16 | P10200 | P89439 | Tegument protein |

| UL17 | CVC1 | P10201 | Processing and packaging DNA | |

| UL18 | TRX2 | P10202 | P89441 | Capsid protein |

| UL19 | VP5; ICP5 | P06491 | P89442 | Major capsid protein |

| UL20 | UL20 | P10204 | P89443 | Membrane protein |

| UL21 | UL21 | P10205 P09855 | P89444 | Tegument protein[54] |

| UL22 | Glycoprotein H | P06477 | P89445 | Surface and membrane |

| UL23 | Thymidine kinase | O55259 | Peripheral to DNA replication | |

| UL24 | UL24 | P10208 | unknown | |

| UL25 | UL25 | P10209 | Processing and packaging DNA | |

| UL26 | P40; VP24; VP22A; UL26.5 (HHV2 short isoform) | P10210 | P89449 | Capsid protein |

| UL27 | Glycoprotein B | A1Z0P5 | P08666 | Surface and membrane |

| UL28 | ICP18.5 | P10212 | Processing and packaging DNA | |

| UL29 | UL29; ICP8 | Q2MGU6 | Major DNA-binding protein | |

| UL30 | DNA polymerase | Q4ACM2 | DNA replication | |

| UL31 | UL31 | Q25BX0 | Nuclear matrix protein | |

| UL32 | UL32 | P10216 | Envelope glycoprotein | |

| UL33 | UL33 | P10217 | Processing and packaging DNA | |

| UL34 | UL34 | P10218 | Inner nuclear membrane protein | |

| UL35 | VP26 | P10219 | Capsid protein | |

| UL36 | UL36 | P10220 | Large tegument protein | |

| UL37 | UL37 | P10216 | Capsid assembly | |

| UL38 | UL38; VP19C | P32888 | Capsid assembly and DNA maturation | |

| UL39 | UL39; RR-1; ICP6 | P08543 | Ribonucleotide reductase (large subunit) | |

| UL40 | UL40; RR-2 | P06474 | Ribonucleotide reductase (small subunit) | |

| UL41 | UL41; VHS | P10225 | Tegument protein; virion host shutoff[42] | |

| UL42 | UL42 | Q4H1G9 | DNA polymerase processivity factor | |

| UL43 | UL43 | P10227 | Membrane protein | |

| UL44 | Glycoprotein C | P10228 | Q89730 | Surface and membrane |

| UL45 | UL45 | P10229 | Membrane protein; C-type lectin[55] | |

| UL46 | VP11/12 | P08314 | Tegument proteins | |

| UL47 | UL47; VP13/14 | P10231 | Tegument protein | |

| UL48 | VP16 (Alpha-TIF) | P04486 | P68336 | Virion maturation; activate IE genes by interacting with the cellular transcription factors Oct-1 and HCF. Binds to the sequence 5'TAATGARAT3'. |

| UL49 | UL49A | O09800 | Envelope protein | |

| UL50 | UL50 | P10234 | dUTP diphosphatase | |

| UL51 | UL51 | P10234 | Tegument protein | |

| UL52 | UL52 | P10236 | DNA helicase/primase complex protein | |

| UL53 | Glycoprotein K | P68333 | Surface and membrane | |

| UL54 | IE63; ICP27 | P10238 | Transcriptional regulation and inhibition of the STING signalsome[56] | |

| UL55 | UL55 | P10239 | Unknown | |

| UL56 | UL56 | P10240 | Unknown | |

| Inverted repeat long (IRL) | ||||

| Inverted repeat short (IRS) | ||||

| Unique short (US) | ||||

| US1 | ICP22; IE68 | P04485 | Viral replication | |

| US2 | US2 | P06485 | Unknown | |

| US3 | US3 | P04413 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase | |

| US4 | Glycoprotein G | P06484 | P13290 | Surface and membrane |

| US5 | Glycoprotein J | P06480 | Surface and membrane | |

| US6 | Glycoprotein D | A1Z0Q5 | Q69467 | Surface and membrane |

| US7 | Glycoprotein I | P06487 | Surface and membrane | |

| US8 | Glycoprotein E | Q703F0 | P89475 | Surface and membrane |

| US9 | US9 | P06481 | Tegument protein | |

| US10 | US10 | P06486 | Capsid/Tegument protein | |

| US11 | US11; Vmw21 | P56958 | Binds DNA and RNA | |

| US12 | ICP47; IE12 | P03170 | Inhibits MHC class I pathway by preventing binding of antigen to TAP | |

| Terminal repeat short (TRS) | ||||

| RS1 | ICP4; IE175 | P08392 | Major transcriptional activator. Essential for progression beyond the immediate-early phase of infection. IEG transcription repressor. | |

Gene expression

editHSV genes are expressed in 3 temporal classes: immediate early (IE or α), early (E or ß) and late (γ) genes. However, the progression of viral gene expression is rather gradual than in clearly distinct stages. Immediate early genes are transcribed right after infection and their gene products activate transcription of the early genes. Early gene products help to replicate the viral DNA. Viral DNA replication, in turn, stimulates the expression of the late genes, encoding the structural proteins.[26]

Transcription of the immediate early (IE) genes begins right after virus DNA enters the nucleus. All virus genes are transcribed by host RNA polymerase II. Although host proteins are sufficient for virus transcription, viral proteins are necessary for the transcription of certain genes.[26] For instance, VP16 plays an important role in IE transcription and the virus particle apparently brings it into the host cell, so that it does not need to be produced first. Similarly, the IE proteins RS1 (ICP4), UL54 (ICP27), and ICP0 promote the transcription of the early (E) genes. Like IE genes, early gene promoters contain binding sites for cellular transcription factors. One early protein, ICP8, is necessary for both transcription of late genes and DNA replication.[26]

Later in the life cycle of HSV, expression of immediate early and early genes is shut down. This is mediated by specific virus proteins, e.g. ICP4, which represses itself by binding to elements in its own promoter. As a consequence, the down-regulation of ICP4 levels leads to a reduction of early and late gene expression, as ICP4 is important for both.[26]

Importantly, HSV shuts down host cell RNA, DNA and protein synthesis to direct cellular resources to virus production. First, the virus protein vhs induces the degradation of existing mRNAs early in infection. Other viral genes impede cellular transcription and translation. For instance, ICP27 inhibits RNA splicing, so that virus mRNAs (which are usually not spliced) gain an advantage over host mRNAs. Finally, virus proteins destabilize certain cellular proteins involved in the host cell cycle, so that both cell division and host cell DNA replication disturbed in favor of virus replication.[26]

Evolution

editThe herpes simplex 1 genomes can be classified into six clades.[57] Four of these occur in East Africa, one in East Asia and one in Europe and North America. This suggests that the virus may have originated in East Africa. The most recent common ancestor of the Eurasian strains appears to have evolved ~60,000 years ago.[58] The East Asian HSV-1 isolates have an unusual pattern that is currently best explained by the two waves of migration responsible for the peopling of Japan.[58]

Herpes simplex 2 genomes can be divided into two groups: one is globally distributed and the other is mostly limited to sub Saharan Africa.[59] The globally distributed genotype has undergone four ancient recombinations with herpes simplex 1. It has also been reported that HSV-1 and HSV-2 can have contemporary and stable recombination events in hosts simultaneously infected with both pathogens. All of the cases are HSV-2 acquiring parts of the HSV-1 genome, sometimes changing parts of its antigen epitope in the process.[60]

The mutation rate has been estimated to be ~1.38×10−7 substitutions/site/year.[57] In clinical setting, mutations in either the thymidine kinase gene or DNA polymerase gene have caused resistance to aciclovir. However, most of the mutations occur in the thymidine kinase gene rather than the DNA polymerase gene.[61]

Another analysis has estimated the mutation rate in the herpes simplex 1 genome to be 1.82×10−8 nucleotide substitution per site per year. This analysis placed the most recent common ancestor of this virus ~710,000 years ago.[62]

Herpes simplex 1 and 2 diverged about 6 million years ago.[60]

Treatment

editSimilar to other herpesviridae, the herpes simplex viruses establish latent lifelong infection, and thus cannot be eradicated from the body with current treatments.[63]

Treatment usually involves general-purpose antiviral drugs that interfere with viral replication, reduce the physical severity of outbreak-associated lesions, and lower the chance of transmission to others. Studies of vulnerable patient populations have indicated that daily use of antivirals such as aciclovir[64] and valaciclovir can reduce reactivation rates.[15] The extensive use of antiherpetic drugs has led to the development of some drug resistance,[citation needed] which in turn may lead to treatment failure. Therefore, new sources of drugs are broadly investigated to address the problem. In January 2020, a comprehensive review article was published that demonstrated the effectiveness of natural products as promising anti-HSV drugs.[65] Pyrithione, a zinc ionophore, has shown antiviral activity against herpes simplex.[66]

Alzheimer's disease

editIn 1979, it was reported that there is a possible link between HSV-1 and Alzheimer's disease, in people with the epsilon4 allele of the gene APOE.[67] HSV-1 appears to be particularly damaging to the nervous system and increases one's risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. The virus interacts with the components and receptors of lipoproteins, which may lead to the development of Alzheimer's disease.[68] This research identifies HSVs as the pathogen most clearly linked to the establishment of Alzheimer's.[69] According to a study done in 1997, without the presence of the gene allele, HSV-1 does not appear to cause any neurological damage or increase the risk of Alzheimer's.[70] However, a more recent prospective study published in 2008 with a cohort of 591 people showed a statistically significant difference between patients with antibodies indicating recent reactivation of HSV and those without these antibodies in the incidence of Alzheimer's disease, without direct correlation to the APOE-epsilon4 allele.[71]

The trial had a small sample of patients who did not have the antibody at baseline, so the results should be viewed as highly uncertain. In 2011, Manchester University scientists showed that treating HSV1-infected cells with antiviral agents decreased the accumulation of β-amyloid and tau protein and also decreased HSV-1 replication.[72]

A 2018 retrospective study from Taiwan on 33,000 patients found that being infected with herpes simplex virus increased the risk of dementia 2.56 times (95% CI: 2.3-2.8) in patients not receiving anti-herpetic medications (2.6 times for HSV-1 infections and 2.0 times for HSV-2 infections). However, HSV-infected patients who were receiving anti-herpetic medications (e.g., acyclovir, famciclovir, ganciclovir, idoxuridine, penciclovir, tromantadine, valaciclovir, or valganciclovir) showed no elevated risk of dementia compared to patients uninfected with HSV.[73]

Multiplicity reactivation

editMultiplicity reactivation (MR) is the process by which viral genomes containing inactivating damage interact within an infected cell to form a viable viral genome. MR was originally discovered with the bacterial virus bacteriophage T4, but was subsequently also found with pathogenic viruses including influenza virus, HIV-1, adenovirus simian virus 40, vaccinia virus, reovirus, poliovirus and herpes simplex virus.[74]

When HSV particles are exposed to doses of a DNA damaging agent that would be lethal in single infections, but are then allowed to undergo multiple infection (i.e. two or more viruses per host cell), MR is observed. Enhanced survival of HSV-1 due to MR occurs upon exposure to different DNA damaging agents, including methyl methanesulfonate,[75] trimethylpsoralen (which causes inter-strand DNA cross-links),[76][77] and UV light.[78] After treatment of genetically marked HSV with trimethylpsoralen, recombination between the marked viruses increases, suggesting that trimethylpsoralen damage stimulates recombination.[76] MR of HSV appears to partially depend on the host cell recombinational repair machinery since skin fibroblast cells defective in a component of this machinery (i.e. cells from Bloom's syndrome patients) are deficient in MR.[78]

These observations suggest that MR in HSV infections involves genetic recombination between damaged viral genomes resulting in production of viable progeny viruses. HSV-1, upon infecting host cells, induces inflammation and oxidative stress.[79] Thus it appears that the HSV genome may be subjected to oxidative DNA damage during infection, and that MR may enhance viral survival and virulence under these conditions.[citation needed]

Use as an anti-cancer agent

editModified Herpes simplex virus is considered as a potential therapy for cancer and has been extensively clinically tested to assess its oncolytic (cancer killing) ability.[80] Interim overall survival data from Amgen's phase 3 trial of a genetically attenuated herpes virus suggests efficacy against melanoma.[81]

Use in neuronal connection tracing

editHerpes simplex virus is also used as a transneuronal tracer defining connections among neurons by virtue of traversing synapses.[82]

Other related outcomes

editHSV-2 is the most common cause of Mollaret's meningitis.[83] HSV-1 can lead to potentially fatal cases of herpes simplex encephalitis.[84] Herpes simplex viruses have also been studied in the central nervous system disorders such as multiple sclerosis, but research has been conflicting and inconclusive.[85]

Following a diagnosis of genital herpes simplex infection, patients may develop an episode of profound depression. In addition to offering antiviral medication to alleviate symptoms and shorten their duration, physicians must also address the mental health impact of a new diagnosis. Providing information on the very high prevalence of these infections, their effective treatments, and future therapies in development may provide hope to patients who are otherwise demoralized.[citation needed]

HSV infection was found to increase all cause mortality in Denmark: 19.3% excess one-year mortality for HSV-1 and 5.3% for HSV-2 at the first year of infection. Additionally, lower employment rates and higher disability pension rates were observed.[86]

Research

editThere exist commonly used vaccines to some herpesviruses, such as the veterinary vaccine HVT/LT (Turkey herpesvirus vector laryngotracheitis vaccine). However, it prevents atherosclerosis (which histologically mirrors atherosclerosis in humans) in target animals vaccinated.[87][88] The only human vaccines available for herpesviruses are for Varicella zoster virus, given to children around their first birthday to prevent chickenpox (varicella), or to adults to prevent an outbreak of shingles (herpes zoster). There is, however, no human vaccine for herpes simplex viruses. As of 2022, there are active pre-clinical and clinical studies underway on herpes simplex in humans; vaccines are being developed for both treatment and prevention.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ a b c Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 555–62. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ Chayavichitsilp P, Buckwalter JV, Krakowski AC, Friedlander SF (April 2009). "Herpes simplex". Pediatr Rev. 30 (4): 119–29, quiz 130. doi:10.1542/pir.30-4-119. PMID 19339385. S2CID 34735917.

- ^ "Herpes simplex virus". World Health Organization. 31 January 2017.

- ^ "Prevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and 2" (PDF). CDC NCHS Data Brief. 16 February 2020.

- ^ Straface G, Selmin A, Zanardo V, De Santis M, Ercoli A, Scambia G (2012). "Herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy". Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012: 385697. doi:10.1155/2012/385697. PMC 3332182. PMID 22566740.

- ^ "Herpes simplex virus". World Health Organization. 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- ^ Stephenson M (2020-09-09). "How to Manage Ocular Herpes". Review of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ "Herpes simplex". DermNet NZ — New Zealand Dermatological Society. 2006-09-16. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ^ Johnston C, Magaret A, Son H, Stern M, Rathbun M, Renner D, et al. (November 2022). "Viral Shedding 1 Year Following First-Episode Genital HSV-1 Infection". JAMA. 328 (17): 1730–1739. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.19061. PMC 9588168. PMID 36272098.

- ^ Schiffer JT, Mayer BT, Fong Y, Swan DA, Wald A (2014). "Herpes simplex virus-2 transmission probability estimates based on quantity of viral shedding". J R Soc Interface. 11 (95): 20140160. doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.0160. PMC 4006256. PMID 24671939.

- ^ a b Johnston C, Koelle DM, Wald A (Dec 2011). "HSV-2: in pursuit of a vaccine". J Clin Invest. 121 (12): 4600–9. doi:10.1172/JCI57148. PMC 3223069. PMID 22133885.

- ^ Sperling RS, Fife KH, Warren TJ, Dix LP, Brennan CA (March 2008). "The effect of daily valacyclovir suppression on herpes simplex virus type 2 viral shedding in HSV-2 seropositive subjects without a history of genital herpes". Sex Transm Dis. 35 (3): 286–90. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815b0132. PMID 18157071. S2CID 20687438.

- ^ Wald A, Langenberg AG, Link K, Izu AE, Ashley R, Warren T, et al. (June 2001). "Effect of condoms on reducing the transmission of herpes simplex virus type 2 from men to women". JAMA. 285 (24): 3100–3106. doi:10.1001/jama.285.24.3100. PMID 11427138.

- ^ a b Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A (December 2007). "Genital herpes". Lancet. 370 (9605): 2127–2137. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61908-4. PMID 18156035. S2CID 40916450.

- ^ a b Koelle DM, Corey L (2008). "Herpes simplex: insights on pathogenesis and possible vaccines". Annual Review of Medicine. 59: 381–95. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.59.061606.095540. PMID 18186706.

- ^ "EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT HERPES". 2017-12-11.

- ^ Corey L, Wald A (October 2009). "Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (14): 1376–1385. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0807633. PMC 2780322. PMID 19797284.

- ^ Usatine RP, Tinitigan R (November 2010). "Nongenital herpes simplex virus". American Family Physician. 82 (9): 1075–1082. PMID 21121552.

- ^ Kimberlin DW (February 2007). "Herpes simplex virus infections of the newborn". Seminars in Perinatology. 31 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2007.01.003. PMID 17317423.

- ^ "Mijn kind heeft blaasjes in de mond door herpes | Thuisarts.nl". www.thuisarts.nl (in Dutch). 21 September 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ "Can You Catch STDs From A Toilet Seat?". mylabbox.com. 2019-02-12. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ García-García B, Galache-Osuna C, Coto-Segura P, Suárez-Casado H, Mallo-García S, Jiménez JS (February 2013). "Unusual presentation of herpes simplex virus infection in a boxer: 'Boxing glove herpes'". The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 54 (1): e22–e24. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2011.00815.x. PMID 23373892. S2CID 11353611.

- ^ Suissa CA, Upadhyay R, Dabney MD, Mack RJ, Masica D, Margulies BJ (March 2023). "Investigating the survival of herpes simplex virus on toothbrushes and surrogate phallic devices". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 34 (3): 152–158. doi:10.1177/09564624221142380. PMID 36448203. S2CID 254095088.

- ^ Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RC, eds. (2012-01-01). "Chapter 1 - Vesiculobullous Diseases". Oral Pathology (Sixth ed.). St. Louis: W.B. Saunders. pp. 1–21. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4557-0262-6.00001-X. hdl:20.500.12613/9321. ISBN 978-1-4557-0262-6.

- ^ Looker KJ, Elmes JA, Gottlieb SL, Schiffer JT, Vickerman P, Turner KM, et al. (December 2017). "Effect of HSV-2 infection on subsequent HIV acquisition: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 17 (12): 1303–1316. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30405-X. PMC 5700807. PMID 28843576.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor TJ, Brockman MA, McNamee EE, Knipe DM (March 2002). "Herpes simplex virus". Frontiers in Bioscience. 7 (1–3): d752–d764. doi:10.2741/taylor. PMID 11861220.

- ^ a b Mettenleiter TC, Klupp BG, Granzow H (2006). "Herpesvirus assembly: a tale of two membranes". Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9 (4): 423–9. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.013. PMID 16814597.

- ^ a b c d e McGeoch DJ, Rixon FJ, Davison AJ (2006). "Topics in herpesvirus genomics and evolution". Virus Res. 117 (1): 90–104. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.002. PMID 16490275.

- ^ Rajcáni J, Andrea V, Ingeborg R (2004). "Peculiarities of herpes simplex virus (HSV) transcription: an overview". Virus Genes. 28 (3): 293–310. doi:10.1023/B:VIRU.0000025777.62826.92. PMID 15266111. S2CID 19737920.

- ^ Isa NF, Bensaude O, Aziz NC, Murphy S (September 2021). "HSV-1 ICP22 Is a Selective Viral Repressor of Cellular RNA Polymerase II-Mediated Transcription Elongation". Vaccines. 9 (10): 1054. doi:10.3390/vaccines9101054. PMC 8539892. PMID 34696162.

- ^ a b Clarke RW (2015). "Forces and Structures of the Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Entry Mechanism". ACS Infectious Diseases. 1 (9): 403–415. doi:10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00059. PMID 27617923.

- ^ a b Subramanian RP, Geraghty RJ (2007). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 mediates fusion through a hemifusion intermediate by sequential activity of glycoproteins D, H, L, and B". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (8): 2903–8. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.2903S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608374104. PMC 1815279. PMID 17299053.

- ^ Akhtar J, Shukla D (2009). "Viral entry mechanisms: Cellular and viral mediators of herpes simplex virus entry". FEBS Journal. 276 (24): 7228–7236. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07402.x. PMC 2801626. PMID 19878306.

- ^ Tunnicliffe RB, Hu WK, Wu MY, Levy C, Mould AP, McKenzie EA, et al. (October 2019). Damania B (ed.). "Molecular Mechanism of SR Protein Kinase 1 Inhibition by the Herpes Virus Protein ICP27". mBio. 10 (5): e02551–19. doi:10.1128/mBio.02551-19. PMC 6805999. PMID 31641093.

- ^ a b Cardone G, Winkler DC, Trus BL, Cheng N, Heuser JE, Newcomb WW, et al. (May 2007). "Visualization of the Herpes Simplex Virus Portal in situ by Cryo-electron Tomography". Virology. 361 (2): 426–34. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.047. PMC 1930166. PMID 17188319.

- ^ a b Trus BL, Cheng N, Newcomb WW, Homa FL, Brown JC, Steven AC (November 2004). "Structure and Polymorphism of the UL6 Portal Protein of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1". Journal of Virology. 78 (22): 12668–71. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.22.12668-12671.2004. PMC 525097. PMID 15507654.

- ^ a b Nellissery JK, Szczepaniak R, Lamberti C, Weller SK (2007-06-20). "A Putative Leucine Zipper within the Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 UL6 Protein Is Required for Portal Ring Formation". Journal of Virology. 81 (17): 8868–77. doi:10.1128/JVI.00739-07. PMC 1951442. PMID 17581990.

- ^ Newcomb WW, Booy FP, Brown JC (2007). "Uncoating the Herpes Simplex Virus Genome". J. Mol. Biol. 370 (4): 633–42. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.023. PMC 1975772. PMID 17540405.

- ^ Berger C, Xuereb S, Johnson DC, Watanabe KS, Kiem HP, Greenberg PD, et al. (May 2000). "Expression of herpes simplex virus ICP47 and human cytomegalovirus US11 prevents recognition of transgene products by CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes". Journal of Virology. 74 (10): 4465–73. doi:10.1128/jvi.74.10.4465-4473.2000. PMC 111967. PMID 10775582.

- ^ Roy S, Sukla S, De A, Biswas S (January 2022). "Non-cytopathic herpes simplex virus type-1 isolated from acyclovir-treated patients with recurrent infections". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 1345. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.1345R. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05188-w. PMC 8789845. PMID 35079057.

- ^ Adang LA, Parsons CH, Kedes DH (2006). "Asynchronous Progression through the Lytic Cascade and Variations in Intracellular Viral Loads Revealed by High-Throughput Single-Cell Analysis of Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Infection". J. Virol. 80 (20): 10073–82. doi:10.1128/JVI.01156-06. PMC 1617294. PMID 17005685.

- ^ a b Matis J, Kúdelová M (2001). "Early shutoff of host protein synthesis in cells infected with herpes simplex viruses". Acta Virol. 45 (5–6): 269–77. doi:10.2217/fvl.11.24. hdl:1808/23396. PMID 12083325.

- ^ Taddeo B, Roizman B (2006). "The Virion Host Shutoff Protein (UL41) of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Is an Endoribonuclease with a Substrate Specificity Similar to That of RNase A". J. Virol. 80 (18): 9341–5. doi:10.1128/JVI.01008-06. PMC 1563938. PMID 16940547.

- ^ Skepper JN, Whiteley A, Browne H, Minson A (June 2001). "Herpes Simplex Virus Nucleocapsids Mature to Progeny Virions by an Envelopment → Deenvelopment → Reenvelopment Pathway". J. Virol. 75 (12): 5697–702. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.12.5697-5702.2001. PMC 114284. PMID 11356979.

- ^ Granzow H, Klupp BG, Fuchs W, Veits J, Osterrieder N, Mettenleiter TC (April 2001). "Egress of Alphaherpesviruses: Comparative Ultrastructural Study". J. Virol. 75 (8): 3675–84. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.8.3675-3684.2001. PMC 114859. PMID 11264357.

- ^ Jeffrey I Cohen (4 May 2020). "Herpesvirus latency". Journal of Clinical Investigation. doi:10.1172/JCI136225. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 7324166. PMID 32364538. Wikidata Q94509178.

- ^ a b Pinnoji RC, Bedadala GR, George B, Holland TC, Hill JM, Hsia SC (2007). "Repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor/neuronal restrictive silencer factor (REST/NRSF) can regulate HSV-1 immediate-early transcription via histone modification". Virol. J. 4: 56. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-4-56. PMC 1906746. PMID 17555596.

- ^ Bedadala GR, Pinnoji RC, Hsia SC (2007). "Early growth response gene 1 (Egr-1) regulates HSV-1 ICP4 and ICP22 gene expression". Cell Res. 17 (6): 546–55. doi:10.1038/cr.2007.44. PMC 7092374. PMID 17502875.

- ^ Roizman B, Gu H, Mandel G (2005). "The first 30 minutes in the life of a virus: unREST in the nucleus". Cell Cycle. 4 (8): 1019–21. doi:10.4161/cc.4.8.1902. PMID 16082207.

- ^ Davidson AJ (2007-08-16). "Comparative analysis of the genomes". Human Herpesviruses. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82714-0. PMID 21348122.

- ^ Slobedman B, Zhang X, Simmons A (January 1999). "Herpes simplex virus genome isomerization: origins of adjacent long segments in concatemeric viral DNA". Journal of Virology. 73 (1): 810–3. doi:10.1128/JVI.73.1.810-813.1999. PMC 103895. PMID 9847394.

- ^ "Search in UniProt Knowledgebase (Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL) for: HHV1". expasy.org.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Smith MC, Boutell C, Davido DJ (2011). "HSV-1 ICP0: paving the way for viral replication". Future Virology. 6 (4): 421–429. doi:10.2217/fvl.11.24. PMC 3133933. PMID 21765858.

- ^ Vittone V, Diefenbach E, Triffett D, Douglas MW, Cunningham AL, Diefenbach RJ (2005). "Determination of Interactions between Tegument Proteins of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1". J. Virol. 79 (15): 9566–71. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.15.9566-9571.2005. PMC 1181608. PMID 16014918.

- ^ Wyrwicz LS, Ginalski K, Rychlewski L (2007). "HSV-1 UL45 encodes a carbohydrate binding C-type lectin protein". Cell Cycle. 7 (2): 269–71. doi:10.4161/cc.7.2.5324. PMID 18256535.

- ^ Christensen MH, Jensen SB, Miettinen JJ, Luecke S, Prabakaran T, Reinert LS, et al. (July 2016). "HSV-1 ICP27 targets the TBK1-activated STING signalsome to inhibit virus-induced type I IFN expression". The EMBO Journal. 35 (13): 1385–99. doi:10.15252/embj.201593458. PMC 4931188. PMID 27234299.

- ^ a b Kolb AW, Ané C, Brandt CR (2013). "Using HSV-1 genome phylogenetics to track past human migrations". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e76267. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876267K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076267. PMC 3797750. PMID 24146849.

- ^ a b Bowden R, Sakaoka H, Ward R, Donnelly P (2006). "Patterns of Eurasian HSV-1 molecular diversity and inferences of human migrations". Infect Genet Evol. 6 (1): 63–74. Bibcode:2006InfGE...6...63B. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2005.01.004. PMID 16376841.

- ^ Burrel S, Boutolleau D, Ryu D, Agut H, Merkel K, Leendertz FH, et al. (July 2017). "Ancient Recombination Events between Human Herpes Simplex Viruses". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (7): 1713–1721. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx113. PMC 5455963. PMID 28369565.

- ^ a b Casto AM, Roychoudhury P, Xie H, Selke S, Perchetti GA, Wofford H, et al. (March 2020). "Large, Stable, Contemporary Interspecies Recombination Events in Circulating Human Herpes Simplex Viruses". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 221 (8): 1271–1279. bioRxiv 10.1101/472639. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz199. PMC 7325804. PMID 31016321.

- ^ Hussin A, Md Nor NS, Ibrahim N (November 2013). "Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of induced acyclovir-resistant clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus type 1". Antiviral Research. 100 (2): 306–13. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.008. PMID 24055837.

- ^ Norberg P, Tyler S, Severini A, Whitley R, Liljeqvist JÅ, Bergström T (2011). "A genome-wide comparative evolutionary analysis of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella zoster virus". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22527. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622527N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022527. PMC 3143153. PMID 21799886.

- ^ "STD Facts – Genital Herpes". 2017-12-11. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Kimberlin DW, Whitley RJ, Wan W, Powell DA, Storch G, Ahmed A, et al. (2011). "Oral acyclovir suppression and neurodevelopment after neonatal herpes". N. Engl. J. Med. 365 (14): 1284–92. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003509. PMC 3250992. PMID 21991950.

- ^ Treml J, Gazdová M, Šmejkal K, Šudomová M, Kubatka P, Hassan ST (January 2020). "Natural Products-Derived Chemicals: Breaking Barriers to Novel Anti-HSV Drug Development". Viruses. 12 (2): 154. doi:10.3390/v12020154. PMC 7077281. PMID 32013134.

- ^ Qiu M, Chen Y, Chu Y, Song S, Yang N, Gao J, et al. (October 2013). "Zinc ionophores pyrithione inhibits herpes simplex virus replication through interfering with proteasome function and NF-κB activation". Antiviral Research. 100 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.001. PMID 23867132.

- ^ Middleton PJ, Petric M, Kozak M, Rewcastle NB, McLachlan DR (May 1980). "Herpes-simplex viral genome and senile and presenile dementias of Alzheimer and Pick". Lancet. 315 (8176): 1038. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(80)91490-7. PMID 6103379. S2CID 11603071.

- ^ Dobson CB, Itzhaki RF (1999). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer's disease". Neurobiol. Aging. 20 (4): 457–65. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(99)00055-X. PMID 10604441. S2CID 23633290.

- ^ Pyles RB (November 2001). "The association of herpes simplex virus and Alzheimer's disease: a potential synthesis of genetic and environmental factors" (PDF). Herpes. 8 (3): 64–8. PMID 11867022.

- ^ Itzhaki RF, Lin WR, Shang D, Wilcock GK, Faragher B, Jamieson GA (January 1997). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain and risk of Alzheimer's disease". Lancet. 349 (9047): 241–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10149-5. PMID 9014911. S2CID 23380460.

- ^ Letenneur L, Pérès K, Fleury H, Garrigue I, Barberger-Gateau P, Helmer C, et al. (2008). "Seropositivity to herpes simplex virus antibodies and risk of Alzheimer's disease: a population-based cohort study". PLOS ONE. 3 (11): e3637. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3637L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003637. PMC 2572852. PMID 18982063.

- ^ Wozniak MA, Frost AL, Preston CM, Itzhaki RF (2011). "Antivirals Reduce the Formation of Key Alzheimer's Disease Molecules in Cell Cultures Acutely Infected with Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25152. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625152W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025152. PMC 3189195. PMID 22003387.

- ^ Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Lin FH, Chiang CP, Yeh CB, Huang SY, et al. (April 2018). "Anti-herpetic Medications and Reduced Risk of Dementia in Patients with Herpes Simplex Virus Infections-a Nationwide, Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan". Neurotherapeutics. 15 (2): 417–429. doi:10.1007/s13311-018-0611-x. PMC 5935641. PMID 29488144.

- ^ Michod RE, Bernstein H, Nedelcu AM (2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–285. Bibcode:2008InfGE...8..267M. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- ^ Das SK (August 1982). "Multiplicity reactivation of alkylating agent damaged herpes simplex virus (type I) in human cells". Mutation Research. 105 (1–2): 15–8. doi:10.1016/0165-7992(82)90201-9. PMID 6289091.

- ^ a b Hall JD, Scherer K (December 1981). "Repair of psoralen-treated DNA by genetic recombination in human cells infected with herpes simplex virus". Cancer Research. 41 (12 Pt 1): 5033–8. PMID 6272987.

- ^ Coppey J, Sala-Trepat M, Lopez B (January 1989). "Multiplicity reactivation and mutagenesis of trimethylpsoralen-damaged herpes virus in normal and Fanconi's anaemia cells". Mutagenesis. 4 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1093/mutage/4.1.67. PMID 2541311.

- ^ a b Selsky CA, Henson P, Weichselbaum RR, Little JB (September 1979). "Defective reactivation of ultraviolet light-irradiated herpesvirus by a Bloom's syndrome fibroblast strain". Cancer Research. 39 (9): 3392–6. PMID 225021.

- ^ Valyi-Nagy T, Olson SJ, Valyi-Nagy K, Montine TJ, Dermody TS (December 2000). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in the murine nervous system is associated with oxidative damage to neurons". Virology. 278 (2): 309–21. doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0678. PMID 11118355.

- ^ Varghese S, Rabkin SD (1 December 2002). "Oncolytic herpes simplex virus vectors for cancer virotherapy". Cancer Gene Therapy. 9 (12): 967–978. doi:10.1038/sj.cgt.7700537. PMID 12522436.

- ^ "Amgen Presents Interim Overall Survival Data From Phase 3 Study Of Talimogene Laherparepvec In Patients With Metastatic Melanoma" (Press release). November 18, 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Norgren RB, Lehman MN (October 1998). "Herpes simplex virus as a transneuronal tracer". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 22 (6): 695–708. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(98)00008-6. PMID 9809305. S2CID 40884240.

- ^ Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine, 19th edition. p. 1179. ISBN 9780071802154.

- ^ "Meningitis - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents". www.antimicrobe.org. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ^ Boukhvalova MS, Mortensen E, Mbaye A, Lopez D, Kastrukoff L, Blanco JC (12 December 2019). "Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Induces Brain Inflammation and Multifocal Demyelination in the Cotton Rat Sigmodon hispidus". J Virol. 94 (1): e01161-19. doi:10.1128/JVI.01161-19. PMC 6912097. PMID 31597775.

- ^ Hansen AB, Vestergaard HT, Dessau RB, Bodilsen J, Andersen NS, Omland LH, et al. (2020). "Long-Term Survival, Morbidity, Social Functioning and Risk of Disability in Patients with a Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 or Type 2 Central Nervous System Infection, Denmark, 2000–2016". Clinical Epidemiology. 12: 745–755. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S256838. PMC 7371560. PMID 32765109.

- ^ Esaki M, Noland L, Eddins T, Godoy A, Saeki S, Saitoh S, et al. (June 2013). "Safety and efficacy of a turkey herpesvirus vector laryngotracheitis vaccine for chickens". Avian Diseases. 57 (2): 192–8. doi:10.1637/10383-092412-reg.1. PMID 24689173. S2CID 23804575.

- ^ Shih JC (22 February 1999). "Animal studies of virus-induced atherosclerosis". Role of Herpesvirus in Artherogenesis. CRC Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-90-5702-321-7.

External links

edit- "Genital Herpes". Public Health Agency of Canada. 2006-05-29.

- Herpes simplex: Host viral protein interactions: A database of HSV-1 interacting host proteins Archived 2010-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- 3D macromolecular structures of the Herpes simplex virus archived in the EM Data Bank(EMDB)