Chipewyan /ˌtʃɪpəˈwaɪən/[4] or Dënesųłinë́ (ethnonym: Dënesųłinë́ yatié[5][6] IPA: [tènɛ̀sũ̀ɬìné jàtʰìɛ́]), often simply called Dëne, is the language spoken by the Chipewyan people of northwestern Canada. It is categorized as part of the Northern Athabaskan language family. It has nearly 12,000 speakers in Canada, mostly in Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories.[7] It has official status only in the Northwest Territories, alongside eight other aboriginal languages: Cree, Tlicho, Gwich'in, Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey and South Slavey.[3][8]

| Chipewyan | |

|---|---|

| Dënesųłinë́ | |

| ᑌᓀ ᓱᒼᕄᓀ ᔭᕠᐁ (Dënesųłinë́ yatié) | |

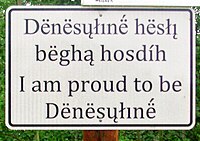

Dënesųłinë́ sign at La Loche Airport | |

| Pronunciation | [tènɛ̀sũ̀ɬìné jàtʰìɛ́] |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | Northern Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba; southern Northwest Territories and Nunavut |

| Ethnicity | 30,910 Chipewyan people (2016 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 11,325, 41% of ethnic population (2016 census)[2] |

| Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Canada (Northwest Territories)[3] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | chp |

| ISO 639-3 | chp |

| Glottolog | chip1261 |

| ELP | Dënesųłiné |

| |

| People | Dënesųłinë́ |

|---|---|

| Language | Dënesųłinë́ yatıé |

| Country | Dënesųłinë́ nëné, Denendeh ᑌᓀᐣᑌᐧ |

Most Chipewyan people now use Dëne and Dënesųłinë́ to refer to themselves as a people and to their language, respectively. The Saskatchewan communities of Fond-du-Lac,[9] Black Lake,[10] Wollaston Lake[11] and La Loche are among these.

Phonology

editConsonants

editThe 39 consonants of Dënesųłinë́:

| Bilabial | Inter- dental |

Dental | Post- alveolar |

Dorsal | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | lateral | plain | labial | ||||||

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ||||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | p ⟨b⟩ | tθ ⟨ddh⟩ | t ⟨d⟩ | ts ⟨dz⟩ | tɬ ⟨dl⟩ | tʃ ⟨j⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ | kʷ ⟨gw⟩ | ʔ ⟨’⟩ |

| aspirated | tθʰ ⟨tth⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | tsʰ ⟨ts⟩ | tɬʰ ⟨tł⟩ | tʃʰ ⟨ch⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | kʷʰ ⟨kw⟩ | |||

| ejective | tθʼ ⟨tthʼ⟩ | tʼ ⟨tʼ⟩ | tsʼ ⟨tsʼ⟩ | tɬʼ ⟨tłʼ⟩ | tʃʼ ⟨chʼ⟩ | kʼ ⟨kʼ⟩ | kʷʼ ⟨kwʼ⟩ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | θ ⟨th⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ɬ ⟨ł⟩ | ʃ ⟨sh⟩ | χ ⟨hh⟩ | χʷ ⟨hhw⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | ||

| voiced | ð ⟨dh⟩ | z ⟨z⟩ | ɮ ⟨l⟩ | ʒ ⟨zh⟩ | ʁ ⟨gh⟩ | ʁʷ ⟨ghw⟩ | ||||

| Tap | ɾ ⟨r⟩ | |||||||||

| Approximant | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | |||||||

The inter-dental series of ⟨ddh⟩, ⟨tth⟩, ⟨tthʼ⟩, ⟨th⟩, and ⟨dh⟩ corresponds to s-like sibilants in other Na-Dené languages.[12]

Vowels

editDënesųłinë́ has vowels of six differing qualities.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Close-mid | e ⟨ë⟩ | o ⟨o⟩ | |

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | ||

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ |

Most vowels can be either

As a result, Dënesųłinë́ has 24 phonemic vowels:

| Front | Central | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | oral | i | iː | u | uː | ||

| nasal | ĩ | ĩː | ũ | ũː | |||

| Close-mid | oral | e | eː | o | oː | ||

| nasal | ẽ | ẽː | õ | õː | |||

| Open-mid | oral | ɛ | ɛː | ||||

| nasal | ɛ̃ | ɛ̃ː | |||||

| Open | oral | a | aː | ||||

| nasal | ã | ãː | |||||

Dënesųłinë́ also has 9 oral and nasal diphthongs of the form vowel + /j/.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close | uj | ũj | ||||

| Mid | ej | ẽj | əj | oj | õj | |

| Open | aj | ãj | ||||

Tone

editDënesųłinë́ has two tones:

- high (marked with acute accents in the orthography: ⟨á é ë́ ı́ ó ú⟩)

- low

Demographics

editIn the 2011 Canada Census 11,860 people chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue. 70.6% were located in Saskatchewan and 15.2% were located in Alberta.[13]

- 7,955 were in Saskatchewan[14]

- 1,680 were in Alberta (the Dene Tha' First Nation a Dëne/South Slavey group (approximately 1000 people) are included in this total)

- 1,005 were in Manitoba

- 450 were in the Northwest Territories

- 70 were in British Columbia

- 45 were in the Yukon

- 20 were in Ontario

Not all were from the historical Chipewyan regions south and east of Great Slave Lake. Approximately 11,000 of those who chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011 are Dëne/Chipewyan with 7,955 (72%) in Saskatchewan, 1,005 (9%) in Manitoba, 510 plus urban dwellers in Alberta and 260 plus urban dwellers in the Northwest Territories. The communities within the Dëne traditional areas are shown below:

Saskatchewan

editThe Dënesųłinë́-speaking communities of Saskatchewan are located in the northern half of the province. The area from the upper Churchill River west of Pinehouse Lake all the way north to Lake Athabasca and from Lake Athabasca east to the north end of Reindeer Lake is home to 7410 people who chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

Prince Albert had 265 residents who chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011, Saskatoon had 165, the La Ronge Population Centre had 55 and Meadow Lake had 30.[14]

3,050 were in the Lake Athabasca-Fond du Lac River area including Black Lake and Wollaston Lake in the communities of:

- Fond-du-Lac 705 out of 874 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Stony Rapids 140 out of 243 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Black Lake (Chicken 224) 1040 out of 1070 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Uranium City (hamlet)

- Camsell Portage (hamlet)

- Wollaston Lake

- Wollaston Post (Lac La Hache 220) 1165 out of 1251 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

3,920 were in the upper Churchill River area including Peter Pond Lake, Churchill Lake, Lac La Loche, Descharme Lake, Garson Lake and Turnor Lake in the communities of:

- La Loche 2,300 out 2,611 chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Clearwater River 720 out of 778 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Black Point (hamlet)

- Bear Creek (hamlet)

- Garson Lake (hamlet)

- Descharme Lake (hamlet)

- Turnor Lake

- Turnor Lake (Birch Narrows First Nation) 70 out of 419 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Dillon (Buffalo River Dene Nation) 330 out of 764 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- St. George's Hill, Saskatchewan 85 out of 100 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Michel Village 55 out of 66 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Buffalo Narrows 35 out of 1153 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Patuanak 35 out of 64 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Patuanak (Wapachewunak 1920) 265 out of 482 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Beauval (La Plonge 192) 25 out of 115 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

Manitoba

editTwo isolated communities are in northern Manitoba. The two Manitoban communities use Dënesųłinë́ syllabics to write their language.

- Lac Brochet (197 A) 720 out of 816 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Tadoule Lake (Churchill 1) 170 out of 321 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

Alberta

editThe Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake Economic Region in the north eastern portion of Alberta from Fort Chipewyan to the Cold Lake area has the following communities. 510 residents of this region chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Fort Chipewyan 45 out of 847 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Fort McKay 30 out of 562 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Janvier (Janvier 194) 145 out of 295 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Janvier South 35 out of 104 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Cold Lake 149 105 out of 594 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

- Cold Lake 149 B, Alberta 25 out of 149 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.

Northwest Territories

editThree communities are located south of Great Slave Lake in Region 5. 260 residents of Region 5 chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Fort Smith 30 out of 2093 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Fort Resolution 95 out of 474 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

- Lutselk'e 120 out of 295 residents chose Dënesųłinë́ as their mother tongue in 2011.[14]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (25 October 2017). "Aboriginal Ancestry Responses (73), Single and Multiple Aboriginal Responses (4), Residence on or off reserve (3), Residence inside or outside Inuit Nunangat (7), Age (8A) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2016 Census – 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Language Highlight Tables, 2016 Census - Aboriginal mother tongue, Aboriginal language spoken most often at home and Other Aboriginal language(s) spoken regularly at home for the population excluding institutional residents of Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 Census – 100% Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Government of Canada, Statistics. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- ^ a b "Official Languages of the Northwest Territories" (PDF). Northwest Territories – Education, Culture and Employment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2015-10-18. (map)

- ^ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- ^ "Official Languages of the Northwest Territories". Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Languages Overview". Office of the Northwest Territories Official Languages Commissioner. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Statistics Canada: 2006 Census Archived October 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Sum of 'Chipewyan' and 'Dene'.

- ^ Northwest Territories Official Languages Act, 1988 Archived March 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (as amended 1988, 1991–1992, 2003)

- ^ "Prince Albert Grand Council (Fond-du-Lac)". Archived from the original on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ "Prince Albert Grand Council (Black Lake)". Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ "Prince Albert Grand Council (Wollaston Lake)". Archived from the original on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ Goddard, Pliny (1912). "Analysis of Cold Lake Dialect, Chipewyan". Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. 10 (2): 67–170.

- ^ "Statistics Canada Table 1 (Aboriginal language families) Canada Census 2011". 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Community Profiles (Canada Census 2011)". 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

Bibliography

edit- Cook, Eung-Do (2004). A Grammar of Dëne Su̜łiné (Chipewyan). Winnipeg: Algonquian and Iroquoian Linguistics. ISBN 0-921064-17-9. OCLC 54906360.

- Cook, Eung-Do (2006). "The Patterns of Consonantal Acquisition and Change in Chipewyan (Dëne Sųłiné)". International Journal of American Linguistics. 72 (2): 236. doi:10.1086/507166. S2CID 143567603.

- De Reuse, Willem (2006). "A Grammar of Dëne Sųłiné (Chipewyan) By Eung‐Do Cook". International Journal of American Linguistics. 72 (4): 535. doi:10.1086/513060.

- Elford, Leon W. (2001). Dene sųłiné yati ditł'ísé = Dene sųłiné reader. Prince Albert, SK: Northern Canada Mission Distributors. ISBN 1-896968-28-7.

- Gessner, Suzanne (2005). "Properties of Tone in Dëne Sųłiné". In Hargus, Sharon; Rice, Keren (eds.). Athabaskan prosody. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science. Vol. 269. John Benjamins. pp. 229–248. doi:10.1075/cilt.269.13ges. ISBN 9789027247834.

- Li, Fang-Kuei (1946). "Chipewyan". In Osgood, C.; Hoijer, H. (eds.). Linguistic Structures of Native America. The Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology. Vol. 6. New York: Viking Fund. pp. 398–423. OCLC 7198204. (Reprinted 1963, 1965, 1967, & 1971, New York: Johnson Reprint Corp.).

External links

edit- First Voices Dene Community Portal

- Our Languages: Dene (Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Centre)

- OLAC resources in and about the Chipewyan language

- Kirkby, William West: The New Testament, translated into the Chipewyan language = ᑎᑎ ᗂᒋ ᕞᐢᕞᒣᐣᕠ (Didi gothi testementi). London, 1881 (Peel 986)