The Indian vulture or long-billed vulture (Gyps indicus) is a bird of prey native to the Indian subcontinent. It is an Old World vulture belonging to the family of Accipitridae. It is a medium-sized vulture with a small, semi-bald head with little feathers, long beak, and wide dark colored wings. It breeds mainly on small cliffs and hilly crags in central India and south India.

| Indian vulture | |

|---|---|

| |

| Indian vulture | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Gyps |

| Species: | G. indicus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gyps indicus | |

| |

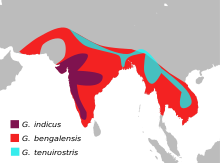

| Distribution in purple | |

The Indian vulture is a keystone species that has been listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2002, as the population has severely declined during the Indian vulture crisis. It is estimated that there are 5,000-15,000 mature individuals in the wild. The main cause of the decline was identified as kidney failure caused by the drug diclofenac, which was commonly given to cattle to reduce joint pain. It is thought that diclofenac poisoned vultures that ate the flesh of dead cattle. Diclofenac bans were enacted in India, Pakistan and Nepal in 2006.

The bird shares its habitat with two other vulture species (namely, the slender-billed vulture (Gyps tenuirostris) and white-rumped vulture (Gyps bengalensis)) in some parts of its range.

Taxonomy

editThe Indian vulture is placed in the genus Gyps (old world vultures), and gets both its common and specific scientific names from its nativity to the Indian subcontinent.[3] The genus name is from Ancient Greek gups meaning "vulture" and the species name is Neo-Latin indicus from the Ancient Greek "indikós" meaning "Indian".[4]

The slender-billed vulture (Gyps tenuirostris) was a sub-species of Indian vulture until 2001. Based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA evidence, it was separated into a different species from the Indian vulture in 2001.[5][6][7]

Distribution and habitat

editThe range of the Indian vulture extended from southeastern Pakistan to south India and to Indochina and the northern Malay Peninsula in the east.[8] It is now extinct in South East Asia with current populations existing mostly in central and peninsular India, south of the Gangetic plains. It is also found in southwest Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal.[6][8]

It is also found in various land-forms ranging from semi-desert to dry foot hills, open fields and cultivable lands near villages, near garbage dumps and slaughter houses in urban areas.[9][10] They are not migratory but travel hundreds of miles in a day scavenging for food. Indian vultures nest on cliffs or high buildings and rarely on trees.[10]

Description

editThe Indian vulture is bulky and medium in size. Its body and covert feathers are pale brown with darker flight feathers. It has white thighs with scattered white fluff and broad wings with short tail feathers.[11] It has a small, bare, dark-brown head with a long featherless neck, dark eyes and a long yellowish beak with a pale green-yellow cere.[8][12] It is 89–103 cm (35–41 in) long and has a wing span of 2.22–2.58 m (7 ft 3 in – 8 ft 6 in).[9]

The bald heads allow them to maintain body temperature in response to the environment. When it is cold, they tuck their necks in closer to their bodies to keep them warm and when it is hot, they extend their necks.[8] Indian vultures have very few feathers on their heads which help them to keep their heads clean when they stick them into the rotting carcasses to feed.[8]

It weighs 5.5–6.3 kg (12–14 lb) and is comparatively smaller than the Eurasian griffon. It is distinguished from that species by its less bulky body and wing coverts.[13]

Behaviour and ecology

editThe Indian vulture is a powerful flier and soars on thermal convection currents. It reaches speeds of 35 km/h (22 mph) when gliding and can fly for six to seven hours continuously.[14] The Indian vulture nests mainly on cliffs and is usually found is small flocks, sometimes with other vulture species.[12]

Diet and feeding

editThe Indian vulture is a keystone species in its habitats and is a scavenging bird, feeding mostly from carcasses of dead animals.[15] It plays a crucial role in the ecosystem by removing rotting meat that would otherwise spread disease.[16] It covers wide areas sometimes ranging hundreds of miles in search of carcasses and mainly uses its eye sight to spot the same.[12]

They are often attracted to large gatherings of other raptors or scavengers as this usually means that there is a carrion nearby. The Indian vultures generally feed on dead cattle and any leftovers by large predators. Individual birds often fight with each other to maintain the best position at the carcass. As Indian long-billed vultures are comparatively smaller than some other species, they have to sometimes back down to let other larger birds.[8]

Lifespan and mortality

editIndian vultures have a lifespan of 40 to 45 years. They sexually mature at five years of age.[17] While vultures in the wild might have a longer lifespan, they are increasingly found close to human habitats. In the human habitats, Indian vultures are prone to higher mortality due to road kills, electrocution on high power lines, collision with trains and other high structures such as windmills.[18][19][20] Apart from this, major cause of death has been NSAIDs including Diclofenac commonly given to cattle to reduce joint pain which believed to have been passed onto the vultures thorough the flesh of dead cattle causing kidney failure and death in vultures.[15]

Reproduction

editIndian vultures nest on cliffs, high buildings, and, more rarely, on trees. They sometimes build nests on old monuments and towers.[10][21][8] A platform of sticks or twigs lined with leaves with the addition of green leaves advertising nest occupancy and fend off parasites.[21]

Indian vultures reach breeding age at about five years old. Nest building starts in September and breeding happens between November and March.[21] They often breed in monogamous pairs and the females lay only one egg a year.[22] The egg is pure white or mottled with rusty spots. Both the parents take turns in incubating the egg and the egg hatches in about 50 days.[10] The nests are often located near water sources such as rivers, lakes or ponds to enable them to maintain the humidity levels in the nests. The nests are located at higher altitudes with nearly 90% of the nests at an altitude of more than 900m.[citation needed]

Status and conservation

editPopulation decline and recovery

editBeginning in the 1990s, the Indian vulture species suffered a 97% population decrease in its range in the Indian subcontinent over a period of 10–15 years.[23] The species is classified as critically endangered in the IUCN Red List since 2002 due to the rapid decline in population.[1] Currently, there are only an estimated 5000 to 15000 birds in the wild.[24]

This is conjunction with the rapid decline in the population of other related vulture species including the slender-billed vulture and white-rumped vulture. Between 2000 and 2007, the annual decline rates of this species averaged over sixteen percent.[24] The cause of this rapid decline was identified as poisoning caused by the veterinary drug diclofenac. Diclofenac is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug commonly given to cattle to reduce joint pain. The drug is believed to have been passed onto the vultures thorough the flesh of dead cattle who were given diclofenac in their last days of life which then causes kidney failure in vultures.[15]

Data modelling revealed that a tiny proportion (about 0.8%) of livestock carcasses containing diclofenac can cause significant crash in vulture populations.[22] The decline in vulture population had a huge socio-economic impact in the region and drastically affected the conservation of the ecological balance. By removing all carrion, vultures had helped decrease pollution, spread of diseases, and suppressed undesirable mammalian scavengers.[25] Without vultures, a large number of animal carcasses were left to rot, posing a serious risk to human health by contaminating water supply and providing a potential breeding ground for infectious germs and proliferation of pests such as rats.[26] The loss of vultures also resulted in a substantial increase in the population of feral dogs, whose bites are the most common cause of human rabies. The feral dog population in India increased by least 5 million, resulting in over 38 million additional dog bites and more than 47,000 extra deaths from rabies, costing $34 billion in economic impact.[15] On average, it was estimated that human mortality rates increased by more than 4% during the period of 2000 to 2005, when vulture population reached the lowest levels.[27]

In March 2006, the government of India announced a ban on the veterinary use of diclofenac. Meloxicam, another NSAID was rapidly metabolized and harmless to vultures was suggested as an acceptable substitute for diclofenac.[28] Nepal banned the manufacture and importation of diclofenac in June 2006 and Pakistan followed suit in September 2006.[29] Pharmaceutical companies were encouraged to the increase in the production of meloxicam aimed at reducing the cost down to diclofenac's own levels to make it more suitable for use. In 2015, the government of India ordered the vial size of the drugs to be reduced to 3ml to reduce the dosage administered to cattle.[22] In 2021, tolfenamic acid was identified as another alternative that is safe for vultures.[30][15]

After banning the drug in 2006, the vulture population rebounded and with the combined population relatively stable till 2011. But, further decline of vulture populations were reported in some states in India.[6] Despite the banning of diclofenac and reduction in usage by about 50%, the drug was still available for veterinary use.[31] There were other compounds like aceclofenac and ketoprofen which were in use and were harmful.[32] In 2008, the government of India enacted a law declaring the sale of diclofenac as a imprisonable offense.[15] Later surveys found that the population was recovering slowly and the decline has been significantly slowed in India, Pakistan and Nepal following a strict ban on the drug.[6][15][33]

Conservation

editCaptive-breeding programmes for the Indian vulture were started to help recover its numbers. As the vultures are long-lived, slow-breeding and notoriously difficult to breed in captivity, the programmes are expected to take longer.[34] The captive-bred birds will be released to the wild when the environment is clear of diclofenac.

In 2014, Saving Asia's Vultures from Extinction programme was announced to start releasing captive-bred birds into the wild by 2016.[35] In 2016, Jatayu Conservation Breeding Centre, Pinjore released captive bred vultures into the wild as part of Asia's first vulture re-introduction program.[36] Small numbers of birds have bred across peninsular India, in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.[37] Three more breeding centers have been setup in the Indian states of West Bengal, Assam and Madhya Pradesh in addition to four smaller facilities in collaboration with zoos.[22]

In 2020, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of Government of India has launched a Vulture Action Plan 2020-25. It aims to step up conservation measures and set up a mechanism to ensure that toxic drugs other than diclofenac are also banned for veterinary use.[32]

In 2010, a small population of Indian vulture and three other species of vultures were discovered in the Moyar river valley in Sathyamangalam Wildlife Sanctuary, where 20 nests were sighted with a population of 40 adults. It was last sighted in the region in the 1970s and the rediscovery is significant to its conservation.[38]

Cultural and economic significance

editIndian vultures are often misunderstood, feared and considered as lowly creatures largely due to their eating habits of feeding on carrion.[39] They play a key ecological role as a keystone species and serve as effective scavengers. In the Indian subcontinent, where there is a large population of cattle and few facilities for incineration and carcass processing, vultures effectively clean up the carcasses offering health benefits and save economical costs.[40]

Jatayu is a demigod in the Hindu epic Ramayana, who has the form of either an eagle or a vulture.[41]

The people of Parsi community in India leave the dead bodies exposed in high towers called Tower of Silence in order for the vultures to feed.[42]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2021). "Gyps indicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22729731A204672586. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Scopoli, J. A. (1786–88). "Aves". Deliciae Flora et Fauna Insubricae Ticini. An account including new descriptions of the birds and mammals collected by Pierre Sonnerat on his voyages. London: C. J. Clay. pp. 7–18.

- ^ Del Hoyo, J.; Collar, N. J. (2014). Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Spain: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 9788496553989.

- ^ Jobling, J. A. (2009). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 183, 205. ISBN 9781408125014.

- ^ O'Neal Campbell, M. (2015). Vultures, their Evolution, Ecology and Conservation. CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781482223620.

- ^ a b c d BirdLife International. "Indian Vulture factsheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Rasmussen, P. C.; Parry, S. J. (2001). The taxonomic status of the "Long-billed" Vulture Gyps indicus. p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Explore Raptors species". Peregrine fund. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ a b Ferguson-Lees, J. & Christie, D. A. (2001). Raptors of the World. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 124. ISBN 0618127623.

- ^ a b c d Scott, D. (2020). Raptor Medicine, Surgery, and Rehabilitation (Third ed.). CABI. p. 42. ISBN 9781789246100.

- ^ BirdLife International (2011). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Birds. Dorling Kindersley. p. 191. ISBN 9781405336161.

- ^ a b c Grewal, B.; Harvey, B. & Pfister, O. (2014). Photographic Guide to the Birds of India and the Indian Subcontinent. Tuttle Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 9781462914852.

- ^ "The Peregrine Fund". The Peregrine Fund. 2010. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "The Indian Long-Billed Vulture". bestanimalreports.com. 5 September 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Burfield, I. & Bowden, C. (2022). "South Asian vultures and diclofenac". Cambridge University. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Exploring keystone species". HHMI. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "Vulture culture: Rescuing the big bird". Economic Times. 24 November 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Deaths of vultures by electrocution go unchecked in Tanahun". Kathmandu post. 23 January 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Four vultures die in Jaisalmer after hitting windmill, wires". Times of India. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Train hits vultures in Jaisalmer, 4 killed". Times of India. 17 November 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ a b c Kushwaha, S. (2016). "Utilisation of green plant material in nests of Long-billed Vultures Gyps indicus in Bundelkhand Region, India". Vulture News. 71. Indian Biodiversity Conservation Society.

- ^ a b c d Iyer, K. (2021). "Born to be wild: India's first captive-bred endangered vultures set free". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Hirschfeld, E.; Swash, A.; Still, R. (2013). The World's Rarest Birds. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9781400844906.

- ^ a b "BirdLife Fact Sheet: Indian vulture". BirdLife International. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Prakash, V.; Bishwakarma, M. C.; Chaudhary, A.; Cuthbert, R.; Dave, R.; Kulkarni, M.; Kumar, S.; Paudel, K. & Ranade, S. (2012). "The Population decline of Gyps Vultures in India and Nepal has slowed since veterinary use of Diclofenac was banned". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e49118. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749118P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049118. PMC 3492300. PMID 23145090.

- ^ Prakash, V.; Pain, D.J.; Cunningham, A.A.; Donald, P.F.; Prakash, N.; Verma, A.; Gargi, R.; Sivakumar, S. & Rahmani, A.R. (2003). "Catastrophic collapse of Indian white-backed Gyps bengalensis and long-billed Gyps indicus vulture populations". Biological Conservation. 109 (3): 381–390. Bibcode:2003BCons.109..381P. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00164-7.

- ^ "How human and ecosystem health are intertwined: Evidence from vulture population collapse in India". Voxdev. 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Adawaren, E. O.; Mukandiwa, L.; Chipangura, J.; Wolter, K.; Naidoo, V. (2019). "Percentage of faecal excretion of meloxicam in the Cape vultures (Gyps corprotheres)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology. 215: 41–46. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2018.10.001. hdl:2263/67172. PMID 30336288. S2CID 53011740.

- ^ McGrath, S. (2007). "The Vanishing". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Pinjarkar, V. (2021). "Second vulture-safe veterinary pain-killer drug identified". Times of India. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Jagga, R. (2011). "Banned diclofenac still kills vultures". Express India. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Diclofenac threat to 7 vulture species". Tribune India. 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Ghai, R. (2019). "Madhya Pradesh's vulture population increases". Times of India. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Central zoo Authority (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Kinver, M. (2014). "Project targets 2016 for Asian vultures release". BBC News. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Asia's first vulture re-introduction programme launched in Haryana". 3 June 2016.

- ^ Oppili, P. (2013). "Long-billed Vulture sighted after 40 years". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Ramakrishnan, B.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Saravanan, M.; Arivazhagan, C. (2010). "Is diclofenac the only culprit for declining population of Gyps vultures in the Moyar Valley". Current Science. 99 (12): 1645–1646.

- ^ "Waiting for the vulture". The Hindu. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "'Vultures are often misunderstood; they play a key ecological role providing society with health benefits'". Times of India. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Jatayu, Jaṭāyu, Jatāyū: 19 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Death in the city: How a lack of vultures threatens Mumbai's 'Towers of Silence'". The Guardian. 26 January 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2023.