Inori (Japanese for "Adorations"), for one or two soloists with orchestra, is a composition by Karlheinz Stockhausen, written in 1973–74 (Nr. 38 in the composer's catalog of works).

| Inori | |

|---|---|

| Orchestral music by Karlheinz Stockhausen | |

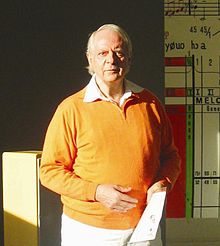

Karlheinz Stockhausen standing in front of the form scheme of Inori, March 2005 | |

| Catalogue | 38 |

| Composed | 1973–74 |

| Scoring |

|

History

editInori is a meditative work. The word inori (祈り) in Japanese means "prayer, invocation, adoration".[1] "It is like an opera with only one character and no singing, only thoughts visible as gesture and audible as reciprocally modulated sound".[2] "The solo part is composed as a melody and is theoretically performable by a melody instrument; however the relationship between solo gesture and orchestra response is so complete that the solo melody is invariably interpreted in silence by a dancer-mime, employing a vocabulary of gestures drawn from a variety of religious practices".[3] The Australian dancer and choreographer Philippa Cullen, who spent some time in Germany working with Stockhausen in 1973, is credited with drawing his attention to choreographic prayer gestures, in particular the mudras of India, which she had been studying.[4]

"Inori is indeed, as the composer insists, a mystical work, but only because there is absolutely no mystification".[5] "Stockhausen recomposed the sign-language of praying, on the basis of chromatic scales of prayer gestures, into a highly differentiated bodily music".[6] Although the score specifies that the soloist part may be performed in any number of ways, including any kind of melodic instrument, to date this has always been performed by mimes, using a set of prayer gestures. Because audiences at early performances were mistakenly perceiving the soloist as improvising to the music, Stockhausen decided to use two parallel soloists in order to make it obvious that the gestures are fully composed.[7]

Stockhausen composed Inori using an Urgestalt or formula, which is "a melodic-rhythmic structure from which the principal characteristics of the work are derived".[8] This melodic formula is divided into five segments, forming a sequence “leading from pure rhythm . . . via dynamics, melody, and harmony, to polyphony:—hence, a progression from the primitive origin of music to a condition of pure intellect. The entire work is a projection of this formula onto a duration of about 70 minutes”.[9] The formula consists of 15 notes, which are

divided into 5 phrases with 5, 3, 2, 1 and 4 pitches respectively. Transferred to the large scale form, these 5 phrases yield the 5 major sections of the work. Each phrase consists . . . of three parts: melody, echo and pause; in the large scale form these become genesis+evolution (=exposition + development)—echo—pause, the echoes being very soft statistical passages, and the 'pauses minimally accompanied solos for the mime. The durations of the melody, measured in crotchets, are converted into minutes to give the lengths of formal divisions and subdivisions.[10]

The most important of the 15 pitches is the G above middle C, which corresponds to the tempo MM = 71 (the "heartbeat" tempo of medieval music theory), to the hand gesture positioned over the heart, and to the syllable "HU", representing the Divine Name.[11]

In addition to these five sections, there is "an unmeasured, transcendental moment".[1]

Stockhausen also composed an introduction to Inori, Vortrag über HU ("Lecture on HU"), Nr. 38½, an hour-long musical analysis of the work, for performance by a singer.[12]

References

edit- ^ a b Stockhausen 1978a, p. 215.

- ^ Maconie 1976, p. 310.

- ^ Maconie 2005, p. 352.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Josipovici 1975, p. 16.

- ^ Peters 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Maconie 1990, p. 236.

- ^ Leonardi 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Maconie 2005, pp. 353–354.

- ^ Toop 1976, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Maconie 1974.

- ^ Stockhausen 1978b.

Sources

edit- Jones, Stephen. 2004. "Philippa Cullen: Dancing the Music". Leonardo Music Journal 14 (Composers Inside Electronics: Music After David Tudor): 64–73.

- Josipovici, Gabriel. 1975. "The Importance of Stockhausen's Inori", Radical Philosophy, no. 11: 15–17. Reprinted 1977 in Josipovici's The Lessons of Modernism and Other Essays, 195–200. London: Macmillan ISBN 0-333-21440-4; Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield ISBN 0-87471-957-7 Second ed. 1987, Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-44094-3 (cased); ISBN 0-333-44095-1 (pbk).

- Leonardi, Gerson. 1998. "Inori: Microcosm/Macrocosm Relationships and a Logic of Perception". Perspectives of New Music 36, no. 2 (Summer): 63–90.

- Maconie, Robin. 1974. "Stockhausen's Inori". Tempo, new series, no. 111 (December): 32–33.

- Maconie, Robin. 1976. The Works of Karlheinz Stockhausen. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315429-3.

- Maconie, Robin. 1990. The Works of Karlheinz Stockhausen, second edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-315477-3.

- Maconie, Robin. 2005. Other Planets: The Music of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Lanham, Maryland, Toronto, Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-5356-6.

- Peters, Günter. 1999. " '...How Creation Is Composed': Spirituality in the Music of Karlheinz Stockhausen". Translated by Mark Schreiber and the author. Perspectives of New Music 37, no. 1 (Winter): 96–131.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1978a. "Inori: Anbetungen für 1 oder 2 Solisten und Orchester (1973–74)", in his Texte zur Musik 4, edited by Christoph von Blumröder, 214–236. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1978b. "Vortrag über HU", in his Texte zur Musik 4, edited by Christoph von Blumröder, 241–242. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag.

- Toop, Richard. 1976. " 'O alter Duft': Stockhausen and the Return to Melody". Studies in Music 10:79–97.

Further reading

edit- Conen, Hermann. 1991. Formel-Komposition: zu Karlheinz Stockhausens Musik der siebziger Jahre. Kölner Schriften zur Neuen Musik, Bd. 1. Mainz and New York: Schott. ISBN 3-7957-1890-2.

- Frisius, Rudolf. 1999. "Musik als Ritual: Karlheinz Stockhausens Komposition Inori". In Musik und Ritual: Fünf Kongreßbeiträge, zwei freie Beiträge und ein Seminarbericht. Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Neue Musik und Musikerziehung Darmstadt 39, edited by Barbara Barthelmes and Helga de la Motte-Haber. Mainz: Schott. ISBN 3-7957-1779-5.

- Riethmüller, Albrecht. 1995. "Stockhausens Diagramm zu Inori". In Töne, Farben, Formen: Über Musik und die Bildenden Künste—Festschrift Elmar Budde zum 60. Geburtstag, edited by Susanne Fontaine, Matthias Brzoska, Elisabeth Schmierer, and Werner Grünzweig, 229–242. Laaber: Laaber-Verlag.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz, in conversation with Rudolph Frisius. 1998. "Es geht aufwärts", in his Texte zur Musik 9, edited by Christoph von Blumröder, 391–512. Kürten: Stockhausen-Verlag.

- Stuke, Franz R. 2003. "Magie der Klänge: INORI (Karlheinz Stockhausen) 4. November 2003, Konzerthaus Dortmund". Opernnetz.de (accessed 21 August 2019).