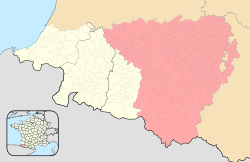

The institutions of the French Basque Country before 1789 were largely based — in this territory, which today forms part of the French department of Pyrénées-Atlantiques and borders on Spain — on a social structure built around the Basque house (etxe), and its intergenerational transmission, as well as the management of common lands. This translates into the shared enjoyment of an undivided property. This joint management by the Basques is considered to be at the origin of the parish assemblies, which form the basis of the deliberative institutions of the Basque Country.

Institutions of the French Basque Country before 1789 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Establishment | |

• Gallo-Roman collegiate system | 1st century |

• Sancho the Great begins his reign over Navarre | 1004 |

| 1021 - 1023 | |

• Marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II, King of England | 1152 |

• Death of Sanche le Fort Soule pays tribute to Navarre | 1234 |

• The English Crown reigns over Soule | 1307 |

• Capture of Mauléon by Charles VII, King of France | 1449 |

• Capture of Bayonne by Charles VII | 1451 |

• Labourd customs | 1514 |

• Soule custom | 1520 |

• Separation of Upper and Lower Navarre | 1530 |

• Low Navarre custom | 1611 |

During the 1st millennium CE, under Roman influence, the region now encompassing Labourd, Lower Navarre, and Soule underwent its initial organizational evolution toward greater democracy. Through the feudal era, these provinces experienced varying fortunes, influenced by Navarrese, French, or English dynasties. Despite efforts to impose centralized or elitist authority, a significant social leveling emerged. Territorial management practices, such as Soule's kayolars, which persist today, originated during this time.

Each of these provinces enjoyed, during the Ancien Régime, an administrative, political, and financial system that gave significant importance to parish assemblies. The most unique of these assemblies, due to the exclusion of the nobility and clergy from decision-making bodies, was the Biltzar of Labourd, in comparison to the Souletin Cour d'ordre and the General Estates of Lower Navarre. The institutions of the three provinces managed, to varying degrees, to preserve part of their privileges until the Revolution; these privileges were regularly renewed through royal letters patent from various suzerains to account for the region's economic poverty, the military devastation caused by repeated Spanish incursions, the maintenance of a significant local militia, and the demonstrated loyalty of the civilian populations to the reigning Crown through their armed mobilization in defense of the borders. Until the end, Lower Navarre maintained and defended a special status as a frontier kingdom, which was acknowledged at the beginning of each new reign by a respectful and protective oath from the new French suzerain.

Despite strong opposition, unanimously shared by the three estates — the nobility, the clergy, and the commoners — the local institutions of the three provinces were definitively replaced by the rules established by the night of August 4, 1789. The abolition of privileges and the establishment of the department of Basses-Pyrénées, which included Béarn, Soule, Lower Navarre, Labourd, and Bayonne, brought an end to the institutional peculiarities and local privileges that had endured for nearly eighteen centuries.

Preliminary clarification

editAs a historical region, the French Basque Country saw its borders evolve significantly before and during the Ancien Régime. For example, while the integration of Lower Navarre into French territory is discussed later in the article, the particular situation of the territories located north of the current department of Pyrénées-Atlantiques during the two centuries preceding the Revolution is not addressed in the following sections.

This aspect is analyzed in detail in the article titled "Political Geography of the Communes of Pyrénées-Atlantiques under the Ancien Régime."

Social foundations

editAlthough the French Basque Country has a rich history, often closely intertwined with that of Aquitaine and even France, its collective ways of life constitute a uniqueness that clearly distinguishes it.[ME 1] In the Basque Country, the house (la maison) held, until the Revolution, a familial and legal status that had significant consequences on rural society's economic and political organization.[1]

The Basque law is a communal law designed by and for a rural population. It was developed from the land collectively owned by all the inhabitants who had settled there, by families, in houses. These houses were the cornerstone of the entire Basque political and social structure. Each, with the cultivated land and the rights to use the common lands, formed an economic unit that allowed an extended family [...] to live. Each [...] was perpetuated through the centuries by a legal system designed for its preservation. Each generation was represented by a responsible person who managed it and had to pass it on, in its entirety, to the next generation [...]. The Basque land belonged to everyone. Property was collective, both at the level of parishes or valleys, which shared vacant lands, and at the level of families, who shared the arable lands [...] In the Basque Country, property included the ancestral house with its belongings and dependencies, movable and immovable property, arable and uncultivated land, farming tools, cattle and domestic animals, as well as usage rights to the common lands, which were held in undivided ownership by all the houses in the parish [...]. The whole constituted an indivisible unit [...]. The necessary corollary of the inalienability of family heritage was the 'right of primogeniture.' Only one child in each generation inherited the family property [...].

— Maïté Lafourcade, Le droit coutumier, p. 38-57[2]

It emerges from Maïté Lafourcade's presentation that traditional Basque society is based on two pillars: one being the house, complemented by its mode of intergenerational transmission, and the other the communal enjoyment of an indivisible property.[ML2 1] The family property is represented by its owner, the etcheko-jaun, or rather its manager. The individual is dominated by the house, to the point of taking its name.[Note 1] The poverty of the land means that it is not enough to sustain a family, and extensive farming is essential, as are the common lands, managed equally by the heads of households. This community also serves to pay off debts or fulfill obligations through labor. This communal management between equals is the origin of the parish assemblies, which have financial, administrative, or political powers in the three Basque provinces of France.[EG1 1]

From Antiquity to the Middle Ages

editThe Gallo-Roman period and the Early Middle Ages

editThe Tarbelles, a proto-Basque Aquitanian people, occupied a territory in the 1st century BC that stretches from the south of the Landes to the present-day French Basque Country, from Chalosse to the valleys of the Adour, and from the rivers of Pau and Oloron. This civitas, established by Augustus between 16 and 13 BC, was divided into pagi, territorial and legal districts, each with a capital.[ME 2] The Suburates, settled in the Saison valley of present-day Soule, seem to have occupied one of these districts, and Hasparren and Bayonne were probably the capitals of such districts.[ME 2]

In the 1st century AD, Rome replaced the traditional Gallic vergobret, the sole executive leader, with a collegiate system, according to the authors.[ME 2] As a result, a municipal senate elected annually a council that governed the civitas, composed of two duumvirs who held a preeminent role, along with two édiles and a quaestor. The municipal senate was the deliberative body; it could have up to one hundred members, chosen for their merit or wealth. Within the Aquitanian pagi, local notables elected two or four magistri, who were bound by the decrees of the senate.[ME 2] The armed forces and criminal justice were under the authority of the governor of Aquitaine, while the duumvirs were responsible for civil law matters.[ME 2]

In the Late Empire, centralization undermined administrative organization: the emperor selected the curator who governed the city, relying on a network of imperial officials and lucrative positions, also known as prébendes.[ME 2] In 364 AD, Valentinian I, to restore a more favorable balance for his subjects, established a protective role of defender of the city, often held by the bishop.[ME 3] The Pierre d'Hasparren,[3] discovered in 1660 and composed of five dactylic hexameters without elisions, which likely adorned the façade of a votive altar, serves as a testament to these changes:

Flamen item dumuir quaestor pagiq. magister

Verus ad Augustum legato munere functus

pro novem optinuit populis seiungere Gallos

Urbe redux genio pagi hanc dedicat aram.

Flamine and also duumvir, quaestor and master of the pagus

Verus, having fulfilled his mission to Augustus,

obtained the separation of the nine peoples from the Gauls;

on his return from the city (of Rome), he dedicated this altar to the genius of the pagus.

In 587, the date of the signing of the Treaty of Andelot, Lapurdum governed an enclave that included Labourd, and probably also the valleys of Baïgorry, Cize, Ossès, and Arberoue,[ME 3] though the institutions of this region are unknown. This situation lasted until the Norman invasions—one of which is doubtful in 844, and a second, confirmed, in 892[EG2 1]—and during the century and a half that followed.[Note 2]

Feudalism

editThe feudal era saw the emergence in Aquitaine, as in the rest of France, of states of various sizes, characterized by significant autonomy.[ME 3] The three Basque provinces of France underwent an evolution during the Middle Ages, influenced by the conflicts and ambitions of the kingdoms of Navarre, England, and France.

Labourd

edit- Sovereigns who ruled Labourd (selection).

In Labourd, the viscounty, seemingly created by Sancho III of Navarre, known as "the Great," between 1021 and 1023, holds direct administrative and judicial powers, while its subjects are consulted on certain matters. Briefly, the viscount possesses the highest ownership over the lands of the viscounty, as well as over inhabited places. Soon, private estates of varying sizes develop,[ME 3] while the viscount retains certain monopolies, such as those of hunting and milling. However, these privileges are short-lived, as he sells the milling monopoly to the people of Labourd in 1106.[ME 4]

Bayonne came under English domination when the Duchess of Aquitaine (Eleanor) married the King of England in 1152.[5] In 1177, Richard the Lionheart separated the city from the viscounty of Labourd, making Ustaritz the new capital. Like many towns of the time, Bayonne was granted a municipal charter in 1215 and freed itself from feudal powers.[Note 3] In 1311, the land of the viscounty still belonged to the King of England—Edward II in this case—who received rents from it. The crown still held part of the vacant lands that had not been acquired in 1106, but the village communities had the right to use these lands. While lower justice was under the jurisdiction of the sixty nobles' houses of the viscounty, high justice remained under the authority of the king.[ME 4] From this time, the two core elements of feudalism—the property and the lordly authority—appear to have been significantly weakened in Labourd. The inquiry ordered in 1311 by Edward II revealed that "...the entire land of Labourd is held immediately from our lord the King of England and Duke of Aquitaine by the nobles and inhabitants of the said land..."[6] The term "noble" here refers to the owners of noble houses, which is distinct from the use of "gentleman" at court.[Note 4] This is why Maïté Lafourcade describes Labourd during this period as a "collective vassal of the King of England."[ML2 3]

Lower Navarre

edit- Kings of France who ruled Lower Navarre

At the turn of the 2nd millennium, Sancho the Great ruled over Navarre, Castile, part of León, Upper Aragon, the Pyrenean valleys, and all of Gascony. Upon the death of Sancho the Strong on April 7, 1234, Navarre passed to the Counts of Champagne, then to the Kings of France—successively Philip the Fair, Louis the Quarreller, Philip the Long, and Charles the Bald—from 1274 to 1328, and finally to the houses of Évreux-Navarre from 1328 to 1425, then to Albret from 1425 to 1512, when the Kingdom of Navarre was invaded by Ferdinand the Catholic.[EG1 2] Sancho the Great had made Labourd a viscounty, and Sancho William, in turn, gave Soule to Viscount William Fort I in 1023. Lower Navarre was solely part of the Kingdom of Navarre—represented in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port since at least 1194 by a châtelain. It became definitively part of Navarre in the 13th century, as a result of the conflict between 1244 and 1245 between the Kings of England (Henry III) and Navarre (Theobald I).[EG1 3] In 1449, Gaston IV of Foix-Béarn seized Mauléon, the capital of Soule, on behalf of King Charles VII of France. While on March 18, 1451, the people of Labourd submitted to the authority of the French king—while retaining their freedoms—on August 20 of the same year, Bayonne returned to the Kingdom of France. Only Lower Navarre was not part of it.

Lower Navarre, a collection of "lands" and valleys under the rule of the King of Navarre, is a territory of freehold, which contrasts with fiefs or censives, and is therefore not subject to any feudal dues, except for the rights of certain landowners. The land is under the sovereignty of the king, who, owns only a few domain lands in the province.[Note 5] Aside from a few local seigneuries and the lower justice held by several houses over certain fivatiers,[Note 6] justice is administered by royal officers.[ME 4] The highest of these is the châtelain of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port for all the tierras de aillent-puertos (another name for tierras de ultra-puertos), who holds administrative, fiscal, and military powers. Outside the châtellenie, the king is also represented by the alcaldes of Cize and Arberoue, the bailes of Mixe and Ostabaret, and the merin of Ossès.[EG2 4] In general, therefore, and aside from the previously mentioned seigneuries, Lower Navarre at the end of the Middle Ages was not a land of feudalism.

The testimonies of the allodial nature of the land in Navarre are abundant. It was to the communities, not to the king, that the primitive for of Navarre of 1237 granted the right to dispose of vacant lands. And Article 1 of Section 29 of the for of Lower Navarre of 1611 proclaims: The pastures of the universities and others will be defended, preserved, and maintained according to the division and observance that has been upheld since time immemorial. Louis XIV, the absolute king par excellence, had to acknowledge, by the Council decrees of February 6, 1669, and May 22, 1672, after an inquiry by de Sève and de Froidour, the property rights of the Navarrese over their cultivated and uncultivated lands, wastelands, waters, and forests [...]. And the edict of April 1694 confirmed their right to hold all their noble and common lands, both private and communal, as freehold of natural and original origin. On February 25, 1782, a deed of notoriety issued by the Chamber of Accounts of Pamplona further confirmed the allodial nature of the lands of both Navarre, whose people and inhabitants have absolute ownership [...].[ML 1]

— Maïté Lafourcade, Les assemblées provinciales du Pays basque français sous l'Ancien régime, p. 591

Lower Navarre had two centers that minted currency: one in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, which disappeared quickly but seems to have still been active in 1385, and the other in Saint-Palais, established in 1351 and operating until 1634.[EG2 3]

On the other hand, the judicial institutions, dating back to before 1512, were organized around three jurisdictions.[7] Two of these concerned commoners: the Alcade Menor—or Alcalde of the Market—and its appellate court, the Alcalde Mayor. Nobles fell directly under the jurisdiction of the King's Court, which was replaced by the Chancellery of Navarre after 1512. These courts had what was referred to as "universal" competence, handling both criminal and civil cases.[EG2 3]

Soule

editSoule stands out among the three Basque provinces due to its stronger imprint of feudalism. The first Viscount of Soule was likely William Fort I, Viscount of Lavedan, who was granted the viscounty of the Basque province in 1023 by Sancho VI William, Duke of Gascony.[EG2 5] William I succeeded him in 1040 but was forced to seek refuge with Étienne de Mauléon, Bishop of Oloron, following an invasion by the Béarnais in retaliation for the assassination of Centulle IV of Béarn by the Souletins in 1058. This protection came at a cost, as William I had to agree that Soule, previously under the Diocese of Dax, would become an archdeaconry of Oloron.[EG2 5]

Starting with Raymond-William II, the 8th Viscount of Soule (1178–1200), local power aligned with Navarre to counter Béarn's influence. In 1234, Raymond-William IV paid homage to Theobald I of Navarre for the castle of Mauléon, a policy continued by his son, Raymond-William V, to oppose England's King Henry III. In 1307, following arbitration by Philip the Fair and Pope Clement V,[EG2 6] the English Crown regained control of Soule, replacing the viscount with a "captain-castellan" based in Mauléon, under the authority of the Seneschal of Gascony. The first known castellan was Oger de la Mothe, whose tenure ended in 1275.[EG2 7] Notable successors included Garcie Arnaud d'Ezpeleta, Fortaner de Batz, Pierre Pelet, Odon de Miossens—responsible for fortifying the castle from 1309 to 1319—and Raymond de Miossens, who signed a treaty with Navarre in 1327 reaffirming the homage of Soule's viscounts to the King of Navarre.[EG2 8] This led to conflicts that were only resolved during the reign of Raymond-William de Caupenne (1350–1390), when Souletins regained their rights after revolting against the royal imposition of albergade dues,[Note 7] restrictions on woodland and water use, and mandatory use of the royal mill.[EG2 8]

At the turn of the 15th century, the histories of the three French Basque provinces intertwined. Charles de Beaumont served as captain-castellan of Mauléon for the King of England, as well as for the King of Navarre in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, and as bailiff of Labourd from 1390 to 1432.[Note 8] This arrangement ended when the French captured Mauléon in 1449. The Beaumont family remained influential in Soule through the Luxe family, whose branch later became the lords of Tardets.[EG2 8]

Unlike its neighbors, the medieval viscount in Soule held sovereign authority over his entire fief and resided in the Mauléon castle for over two centuries, where he presided over a court of justice.[ME 4] From the 13th century,[EG2 10] this role was assumed by the captain-castellan. The court—known as the "Noyer Court" for its sessions under a walnut tree in Licharre[Note 9]—was the sole judicial body in the province. It operated under the captain-castellan, with ten chief lords, known as potestats, and around fifty landholding gentlemen. The court's jurisdiction was universal, covering civil and criminal cases. Appeals could be taken to the mayoral court of Dax or the seneschal court of Les Landes, with the supreme instance being the judge-mage of Guyenne under the English Crown, and later the Bordeaux Parliament. The royal notary of Soule existed as early as 1342, while bailiffs and albergade collectors were present by 1358. Records from 1327 already mention royal messengers.[EG2 10]

Notwithstanding the presence of local fiefs, allodiality — although some lords, such as the Count of Tréville, seize the land, partition it, and lease it for rent — prevails, and the English crown chooses to maintain the social status of the free men of Soule.[ME 4]

A legal institution unique to Soule, the kayolar, has been documented since at least the 12th century, with records of its sale in Larrau in 1105.[EG2 9] According to Marcel Nussy-Saint-Saëns, the kayolar may have been "the mother cell" from which Soule's silvopastoral and communal institutions evolved.[9]

The kayolar system originated during the period when sheep farming, primarily based on transhumance, was the main activity of Souletin peasants. A kayolar is a cabin surrounded by an enclosure used to gather flocks. It was built in the upper and subalpine mountain pastures. The ownership of a kayolar by its lord was subject to two specific usage rights, which defined its unique nature: the exclusive grazing rights over a designated area for the owner's herds, even during periods of vète (restricted grazing), and the right to use trees for building the cabin or for firewood.[Note 10] The purpose of the kayolar was to organize two collective activities: the herding of livestock and the production of cheese. These activities were governed by an assembly, called the artzainbide, held annually on March 25. This gathering of kayolar owners established the terms of usage for the pastures. A second meeting on July 22 brought together all the owners to settle accounts, distribute costs, and share the profits of the summer grazing (estive) based on the number of animals each contributed. Mountain pastures were typically occupied until November 1 at the latest.[EG2 11] This practice persisted into the Ancien Régime, and the Soule customary laws of 1520 provide extensive details about it. By 1506, there were 107 recorded kayolars.[EG2 9] Similar practices were found in the Cize and Baïgorry valleys, although they were less widespread.

Social inequalities and feudal persistence

editIt is impossible to assert that serfdom did not exist during the Middle Ages in the French Basque Country. The study of the Navarrese practice of coillazos, mentioned in the fors of Navarre,[Note 11][11] the botoys in the customs of Soule,[Note 12] or the donats[Note 13] does not clarify whether these groups were in a potentially servile condition.[ME 5]

On the other hand, there was a nobility, though significantly reduced in Labourd after 1311, which enjoyed significant revenues from rents and cens, as well as tithe rights that excluded daughters from inheritance.[ME 6] This nobility, sometimes exempt from ordinary social obligations, had the privilege of initiating legal actions outside the jurisdiction of their local bailiwick. They also benefited from honorary rights in the Church and precedence in religious ceremonies.[Note 14] As was common elsewhere in France under the Ancien Régime, nobles also held the (so-called) privilege of being executed by decapitation in cases of capital punishment, whereas commoners faced hanging as their ultimate penalty.[ML2 5]

Feudalism did not entirely disappear under the Ancien Régime, as evidenced by the claims of the Gramont family or the Count of Tréville. Some lordships, such as those of Urtubie, Sault, Saint-Pée, Garro, Espelette, Macaye, and Gramont, maintained judicial seats, sometimes up until the Revolution.[ME 6] In Soule, every landholding noble (gentilhomme terretenant) had the right to sit on the court of Licharre,[Note 15] a body known as the jugeanterie.[ME 7] In Lower Navarre, some gentlemen held the status of born judges (juges-nés) of royal courts.[ME 7] Most attempts to usurp public rights or claim privileged concessions prompted protests to the king or his council, which often had consequences. For instance, in May 1462, a petition led to King Louis XI revoking the high justice rights previously granted to the Lord of Espelette.[ML2 3]

In Labourd, inhabitants held exclusive political authority, including privileges such as hunting, fishing, bearing arms, and the freedom to build mills. However, public offices and deliberations were reserved for heads of households, excluding non-property owners.[ME 6] Similarly, in Lower Navarre, non-owning commoners were required to pledge fealty and homage within two months of any summons to do so.[ME 7]

Institutions under the Ancien Régime

editThe customs and fors of the Basque provinces were adopted and registered with the Parliament of Bordeaux in the 16th and 17th centuries. The customs of Labourd were registered on May 10, 1514,[ML2 6] those of Soule in 1520, and those of Lower Navarre in 1611.[ME 5] For the Basque provinces under the French Crown—Labourd and Soule—the process of drafting these customs was spurred by Article 125 of the Ordinance of Montils-lès-Tours, signed by Charles VII in 1454.[ML2 6] This ordinance mandated the drafting and registration of all customary laws across the kingdom, under the supervision of bailiwicks. The "General Customs Observed in the Land and Bailiwick of Labourd" resulted from the efforts of a commission formed in 1514 by Mondot de Lamarthone, first president of the Parliament of Bordeaux. Bayonne, which had been separated from the viscounty of Labourd in 1177 and elevated to commune status in 1215 by King John of England, had its own customs as early as 1273, with a revision in 1520.[ML2 6]

Jean d'Ibarrola, a counselor from Sare at the Parliament of Bordeaux, presided over the commission to draft the customs of Soule, appointed by Francis I on March 5, 1520. The "General Customs of Soule" were subsequently registered on October 21, 1520, based on deliberations from the Assembly of the Three Estates of Soule, held at the Licharre Court.[ML2 7]

In 1454, when Charles VII issued his ordinance, Lower Navarre was not yet part of the Kingdom of France. The Fuero General de Navarra and local customs governed administrative life in the province of Ultra-Puertos. On March 14, 1608, King Henry IV of France and Navarre appointed a commission to establish a for for the Basque province, marking a significant departure from the processes in the other provinces. By then, France was moving toward absolutism, characterized by the weakening of customary law.[ML2 7] The drafting of customs in Lower Navarre was carried out by a commission appointed by the king, rather than by local representatives. The resulting text was influenced by Béarnese law and French practices. Its publication sparked discontent among the Navarrese, who demanded the preservation of their liberties and privileges, traditionally sworn to by every Navarrese sovereign upon accession. The letters patent of April 1611, signed by Louis XIII at Fontainebleau, decreed that the custom drafted by the commissioners would henceforth serve as the law in Navarre. It was not until 1644 that the for of Navarre was definitively registered.[ML2 7]

Labourd

edit| Francis I | June 19, 1533

November 29, 1542 |

| Henry II | January 10, 1545 |

| Francis II | November 17, 1551 |

| Charles IX | July 16, 1560

May 5, 1565 |

| Henry III | September 2, 1570

May 25, 1574 |

| Henry IV | January 8, 1575

August 19, 1580 |

| Louis XIII | February 10, 1586

January 22, 1594 |

| Louis XIV | February 7, 1600

July 4, 1606 |

| Philippe II | June 27, 1611 |

| Louis XV | September 15, 1617

May 12, 1629 |

| Louis XVI | July 21, 1631

May 5, 1638 |

During the Ancien Régime, Labourd functioned as a bailiwick reporting solely and directly to the royal authority. It stood out for its significant administrative and financial autonomy. Since the reign of Francis I, Labourd had enjoyed privileges renewed periodically through royal letters patent, lasting between three and nine years. These privileges recognized circumstances such as the region's poverty,[Note 16] its border position exposing it to Spanish incursions and military devastation, and the existence of a provincial militia of 1,000 men—approximately 2% of the population in 1748[ED 5][Note 17]—in exchange for exemption from service in the royal armies,[ML 2] and the loyalty of the people of Labourd to the Crown.[ED 7][Note 18] This loyalty was demonstrated by civilian mobilization to resist Spanish pressures.[Note 19] The renewal of these privileges preserved political and economic freedoms during the Ancien Régime, including exemptions from direct and indirect taxes.[ED 10]

The Labourd, like Lower Navarre and Soule, is a "country of estates," meaning a province that maintained its provincial estates until 1789. These estates primarily negotiated the tax amount with royal intendants, ensured its distribution by parish, and oversaw its collection.[13][14] However, there is a distinct difference compared to most other provincial estates: its representative assembly was open exclusively to the third estate (commoners).[ML 3]

Étienne Dravasa identified the establishment of Labourd's customary law, registered at the Parliament of Bordeaux on June 8, 1514, as the formalization of freedoms gained by the Labourdins as early as 1106. These freedoms were secured through the purchase of rights from Viscount Sanche Garcia over unoccupied lands, including rights typically reserved for the nobility, such as fishing, hunting, and milling.[ED 11] Dravasa rejects the theories of Wentworth Webster[15] and Pierre Cuzacq, who saw the independence of the Labourdins as a resurgence of Roman municipal influence. He attributes their autonomy to English dominance starting in 1152, which lasted three centuries and substituted a royal bailiff for the viscount, whose governance the Plantagenets distrusted.[16]

The first bailiff was installed in Ustaritz in 1247. This representative of the English Crown was supported by a council of prud'hommes (elders) from Labourd, which the Bayonne bishopric described as "elements of popular representation."[ED 12] Documents from the end of English rule in Aquitaine confirm that the Labourdins had the authority to draft and propose administrative documents to the king for their province.[ED 13]

Labourd transitioned through several administrative divisions over time, including Guyenne (1620–1716), Béarn and Auch (1716–1765), and Bordeaux (1787–1790).[ED 14]

The Biltzar—derived from the Basque bilduzahar ("old assembly")—is the representative assembly of the Labourd region. The earliest known written record of its proceedings dates back to October 8, 1567, although its history spans over 700 years.[ED 15] Since deliberations were conducted orally until the 16th century, no medieval records of its activities have survived.[ML 4] Before 1660, the assembly's regulations were established by the governors of Guyenne, but little is known about this period.[ME 8] Its more recent organization stems from a royal council decree dated June 3, 1660, signed by Louis XIV in Saint-Jean-de-Luz.[ED 16][Note 20] From that point onward, the Biltzar came under the Crown's authority, subject to the oversight of royal officials.[ME 8] The Biltzar convened in Ustaritz, at the "royal bailiwick's courtroom and auditorium."

The Biltzar is composed exclusively of representatives from the tiers état (commoners), thereby excluding both the clergy and the nobility. The absence of the latter remains unexplained. The hypothesis attributing their exclusion to poverty, which may have limited their political influence, is contradicted by inventories of at least two aristocrats—Léonard de Caupennes d'Amou, lord of the noble house of Saint-Pée-d'Ibarren (inventory conducted in 1684),[ED 17] and Antoine-Charles de Gramont. Furthermore, the notion that the nobility lacked political power is disproven in practice.[Note 21]

Regarding the clergy's absence, two theories exist. One suggests that since the episcopal residence of the diocese was located in Bayonne, outside the Biltzar's jurisdiction, priests could not attend the assembly in its name.[ED 19] Étienne Dravasa, however, posits that the reason lies in the anticlerical sentiment of the Labourd population, who, despite being deeply religious, rejected the temporal and political power of the clergy.[ED 20]

Participation in parish assemblies, known as kapitala (a Basque adaptation of "capitulaire"), and Biltzar meetings was restricted to the heads of households. Women property owners were generally excluded, often represented by their husbands or eldest sons, though some sessions in the parish of Macaye included up to ten women.[ED 1]

From 1654, the position of bailiff, president of the Biltzar, became an honorary title held by the d'Urtubie family.[ML 5] The king was represented by a lieutenant general and a prosecutor, both from the local area, whose positions were venal. The country's syndic was the true driving force of the assembly, often convening and leading meetings independently. Decisions made by household heads within the Biltzar were considered immediately executable under the syndic general's responsibility.[ML 6] Despite repeated attempts by royal authorities to curtail its power, only the judicial prerogatives of the Biltzar were altered, through the 1660 decree prohibiting it from enacting statutes or ordinances involving imprisonment, banishment, corporal punishment, or financial penalties.[ML 6] As a legislative body, the Biltzar negotiated Treaties of Good Correspondence with Guipuscoa and Biscay during periods of war between France and Spain.[ML 7] It also implemented social welfare measures for impoverished families and approved expenditures for receptions and gifts during visits by dignitaries. Demonstrating its financial independence, the Biltzar managed expenditures—such as those related to road networks—and levied corresponding local taxes. Labourd paid both direct and indirect royal taxes through negotiated agreements, distributed among nobles and parishes, with allocations based on each household's landholdings.[ML 2]

The number of parishes participating in the Biltzar varied over time and across sources. Historical references range from 33 parishes, as stated in one account ("The Land of Labourd with its 33 parishes ... without which the said town [Bayonne] remains a body without members"[17]), to 27 in the 1595 proceedings, 27 noted by Pierre de Rosteguy de Lancre in 1610, and between 38 and 40 in a late 17th-century report by Intendant Louis Bazin de Bezons.[ED 21]

Lower Navarre

editThe representative institutions of Lower Navarre were recognized by the Basque kingdom well before 1530 when Upper and Lower Navarre appear to have definitively separated.[ME 9] In 1512, Ferdinand the Catholic's army invaded the Kingdom of Navarre, which was annexed to the Kingdom of Aragon in 1515, forcing its sovereigns into exile in the tierras de ultra-puertos. The General Estates of Lower Navarre were established in 1523 by Henry II of Navarre, modeled on the Cortes of the Kingdom of Navarre. The 1620 incorporation of Navarre into the Kingdom of France brought no significant changes to their organization, as Louis XIII committed in the Edict of Union[Note 22] and accompanying letters patent dated May 7, 1621, not to "derogate from the Fueros, Franchises, Liberties, Privileges, and Rights [of Navarre]."[ML 4]

The Estates convened annually at the king's request in Saint-Palais, Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, Garris, or La Bastide-Clairence. The assembly comprised the three estates, which met separately. The nobility, defined as those owning noble estates in Navarre, attended without hierarchical distinctions, regardless of whether members were dukes, barons, or viscounts. Their numbers ranged from 103 to 153 according to various sources.[ML 8] The clergy included the bishops of Bayonne and Dax (overseeing Mixe and Ostabarret), the prior of Saint-Palais, the dean (or senior priest) of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, and the priors of the Utxiat and Harambels hospitals. The tiers état (commoners) was represented by deputies elected from towns (Garris, La Bastide-Clairence, Larceveau, Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, and Saint-Palais) and seven territorial groupings (pays): Mixe, the Armendarits-Iholdy-Irissarry triad, Arberoue, Baïgorry, Cize, Ossès, and Ostabarret. Each jurisdiction elected two delegates, except Mixe and the Armendarits-Iholdy-Irissarry group, which elected five[ME 9] (or three, depending on the source[ML 9]). A representative from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port traditionally presided over the group.[ME 10]

- Lintels dating from the Ancien Régime in the communes of Armendarits, Iholdy and Irissarry

-

Iholdy, lintel from 1719.

-

Armendarits, carved rubble.

-

Armendarits, bottle door.

-

Irissarry, 1675 lintel.

In the order of deliberations, which take place after the reading of the grievances by the syndic of the Estates (referred to in the documents as the syndic of the Kingdom), the nobility casts its votes, which are then submitted to the third estate and the clergy. They then meet separately to discuss. Decisions are made by majority vote, each estate having one vote, except in financial matters where the individual votes of the third estate take precedence. Sometimes, the intervention of the King's Council is required to resolve disputes.[ME 10]

Outside of these national assemblies, smaller meetings, called "joint" assemblies, are held, which gather only the nobility and the third estate. At the kingdom level, they are called by the castellan of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port at the syndic's request and, since 1772, subject to the authorization of the intendant.[ME 8] Finally, the representation system included the holding of General Courts specific to the six regions — with the exception of the Armendarits - Iholdy - Irissarry group — which gather the nobility of the respective regions sitting in the Estates, as well as the concerned inhabitants.[ME 8] This system thus establishes a sort of popular referendum between the sessions of the Estates of Lower Navarre.

Alongside the syndic sits a treasurer, whose office became venal under the reign of Louis XIV. The treasurer manages the country's finances and is personally responsible for the collection of royal taxes. In 1730, the treasurer was imprisoned for failing to gather the funds in time.[ML 10] In addition to grievances addressed to the king, the Estates would vote on the amount of the "donation" to be granted to the king, who, if he had not initially set the amount, would then request the largest possible donation: "Dear and well-loved, we ask for a donation, the largest you can..."[18]

Soule

editThe situation of the General Estates of Soule before the publication of the fors in 1520 is very poorly documented.[ME 7] We only have mandates and certain letters patent issued by the kings of England, as well as the 1327 treaty, ratified by the King of Navarre and the "people of Soule."[EG2 7] The first letters patent benefiting Soule were issued by Charles IX on January 18, 1574, and renewed on June 26, 1575, by Henri III.[ED 22]

The king is represented in Soule by the captain-castellan of Mauléon. In this capacity, he is the military leader of the province and presides over the General Estates and the court of justice. He has the prerogative to levy royal taxes, administer lands owned directly by his suzerain, and grant parts of common lands. His direct superior is the seneschal of Gascony, and he commands messengers who communicate his decisions to the parishes of Soule, as well as two bailiffs, one to the north and one to the south, who serve as his police representatives. In this capacity, the bailiffs carry out arrests on behalf of judicial decisions or by order of the captain-castellan.[EG2 7]

After 1520, the Licharre court, the supreme political body known as the Court of Order, was made up of the Grand Body, which included the nobility and clergy, and the third estate, a popular assembly called the Silviet.[ML 11] This court meets at least once a year, on the Sunday following the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, at the request of the general syndic of Soule. It primarily deals with financial matters, managing direct and indirect taxes. It is also a legislative assembly that may clarify or amend unclear or controversial articles of the 1520 custom, and for this purpose, it sends delegations to the King's Council to obtain validation of the province's privileges. Finally, it is responsible for maintaining roads (paths, bridges), stud farms, and the postal system. Socially, it also intervenes in education, health, and assistance to the poor.[ML 12]

The nobility includes the ten potestats — gentlemen who are required by their position to fulfill specific duties in exchange for material benefits[Note 23] — as well as all holders of noble properties. The Bishop of Oloron or his vicar general, the abbot of Sainte-Engrâce, the commanders of Ordiarp, Berraute, and the Hospital of Saint-Blaise, as well as the prior of Larrau, make up the clergy.[ME 7]

- The six royal villages participating in the Silviet

-

Church of Montory.

-

Church of Haux.

-

The Tardets valley by Eugène de Malbos.

-

Church of Sainte-Engrâce.

Soule at this time is divided into three messenger districts, which themselves are divided into seven dégairies (subdivisions).[Note 24] The third estate consists of the dégans — representatives of the seven dégairies (or cantons)[Note 25] — and at least two procurators from the parishes. In addition to the parish representatives, the deputies from the six royal boroughs — Montory, Haux, Barcus, Larrau, Tardets, and Sainte-Engrâce — also participate in the Silviet. The Silviet is the general assembly of the third estate. Meeting in the woods of Libarrenx, it holds the supreme authority. Given the complexity of convening the Silviet, the Grand Body meets alone under the presidency of the governor or his representative, in the presence of the general syndic and the dégans. The deliberations and decisions of the Grand Body are then transmitted to the Silviet and require its formal approval.[ML 14] After presenting the agenda, the representatives of the Silviet return to their parishes to obtain its decision. It is important to note that the participation of representatives in the Silviet is mandatory, under penalty of a fine, unless excused by a codified reason in the customs of Soule.[ME 11]

Within the Court of Order, the Silviet holds a vote just like the Grand Body. The syndic of the third estate — who is also the general syndic of the land, meaning of the Court of Order — and that of the Grand Body are responsible for resolving disagreements. Starting in the 18th century, the final arbitration rests with the president of the Court of Order, or, in the case of financial disputes, with the King's Council.[ML 15] The executive authority is held by the Silviet, which alone elects the general syndic of the land, who is responsible for implementing the decisions. The Silviet primarily debates decisions concerning the use and boundaries of common lands, and its responsibilities can extend to the entire region of Soule.[ML 16]

The Silviet lost its representative role starting in 1730 under pressure from the nobility.[19]

Attacks on Customary Law

editLabourd

editIn the 18th century, Labourd lost its prerogatives regarding the maintenance of the road network, which it had previously managed through corvées (forced labor), within the community limits set by the intendant d'Étigny. In 1778, the intendant of Saint-Maur placed the administration of roads under the responsibility of the engineer of bridges and roads for the Bordeaux generality.[ED 23] As a result, the parishes of Labourd saw an increase in the number of corvée laborers and working days required from this date.[ED 24]

Starting in 1694,[20] the syndic convenes, alongside the Biltzar, "without the interference of the obstacles created by centralization," an assembly of notables "the wisest (sic) and most enlightened that the country has honored with its trust." These meetings take place either in Urrugne, Saint-Pée-sur-Nivelle, Saint-Jean-de-Luz, or Bayonne,[ED 25] and gather "former syndics and the most powerful (sic) or best-informed individuals about the interests of the country," as well as the king's prosecutor in Labourd and, if necessary, representatives of the nobility. The agenda mainly concerns financial matters and addresses issues of little importance or urgent matters. This assembly is similar to the joint assembly of Lower Navarre.[ED 26]

The cost of wars and Louis XIV's policy of liberalities led to very heavy taxation throughout France, but more specifically in Labourd, which had been protected by its privileges. This tax burden included both direct taxes — capitation and twentieths — and indirect taxes such as notarial rights, tobacco, or leather duties.[ED 27]

Lower Navarre

editFrom the beginning, the Navarrese must fight for the recognition of their ancient customs. The for of Lower Navarre is drafted under the influence of Béarnese law, and the original customs are altered or Frenchified. The version published in 1611 imperfectly represents the local legal pluralism. Specifically, the king's oath, which upon his accession pledged to respect the freedoms and privileges of the Navarrese, has disappeared. Despite repeated remonstrations from the Navarrese in 1622 and 1634, the central administration resists, and it is not until 1645 that the for of Lower Navarre is printed.[ML 17]

The syndic of the Kingdom is elected by the Estates from among the representatives of the nobility or the legal body,[21] but from the 17th century onwards, the choice of this lifelong and irremovable position — though not hereditary, despite instances of nepotism in the appointment of a syndic in anticipation when the current syndic becomes too old — is systematically influenced by the intendant, the royal representative.[ML 9]

By the decree of December 21, 1748, the royal council removed the right of the Estates of Navarre to make "any laws, statutes, or regulations," following a long struggle between the Pau court (or Parliament of Navarre) and the regulatory power of the Estates.[Note 26] At this point, Lower Navarre — still calling itself the Kingdom of Navarre — loses its regulatory authority and becomes integrated into the administrative structure of the French Crown.

Soule

editOn November 30, 1727, under pressure from the nobility, the general syndic Armand d'Hegoburu presented the king with a request for deep reform of the Court of Order, aligning it with the other provincial estates of the Crown.[Note 27] On December 14 of the same year, the Silviet rejects the vote of the Grand Body.[ME 11] Unfortunately, by letters patent of June 28, 1730, Louis XIV agrees with the syndic and the aristocracy.[ML 19] As a result, the Silviet is abolished, and the third estate now only has thirteen representatives — the seven dégans and the deputies from the six royal boroughs; these are paid by the general assembly, no longer by the communities that mandate them, and are considered representative, giving them full powers to deliberate and vote independently, thus excluding any popular consultation. The General Estates of Soule are now composed of three estates, rather than two. While the votes of the nobility and clergy are still subject to the approval of the third estate, divergences now require the appointment of two arbitrators for each side, with the final arbitration resting with the president or, in financial matters, the king's council.[ME 11] In practice, the Grand Body now makes the decisions, and the third estate serves as a mere register.

Despite a complaint filed in 1731 to the Parliament of Navarre seeking the restoration of "their old form and custom of deputing and assembling," followed by another against the general syndic Hegoburu and the Count of Trois-Villes for "prevarications and extortions," both of which initially resulted in favorable decisions in the first instance, the King's Council overturns the decisions on October 13, 1731, instructing the "dégans and deputies to execute the letters patent of June 28, 1730, under penalty of being treated as rebels."[ML 19] Until 1733, the third estate and its leaders continued to show signs of opposition, sometimes violently, which ultimately justified the King's Council ruling of May 20, 1733, which prohibits "the dégans and deputies and anyone else from the land of Soule from holding assemblies, deputations, or levying funds without written permission from the intendant of the province."[ML 19]

The Revolution and its consequences

editLabourd

editThe letters patent issued by Louis XVI on January 21, 1789, organizing the Estates General, included Labourd in an electoral district that also encompasses the sénéchaussées of Bayonne, Dax, and Saint-Sever.[EG2 13]

On March 7, 1789, the Biltzar, convened for an extraordinary meeting, appointed syndic Haramboure and two lawyers, d'Ithurbide and d'Hiriart, to draft a protest for Labourd. The three delegates, unsurprisingly given the privileges enjoyed by the Labourdins, highlight the administrative independence of the province, which "has its own leaders, assemblies, constitution, and particular laws," not to mention its bailiwick. They argue that the assembly's decisions, led by Basque deputies, would violate the province's freedom and autonomy, emphasizing that Labourd's unique administrative, customary, linguistic, and cultural identity should only be represented by Basques.[EG2 13]

This protest, supported by Dominique Joseph Garat, received a favorable reception. On March 28, 1789, Louis XVI recognized Labourd's distinct status, agreeing that the province should be represented by four deputies: one for the nobility, one for the clergy, and two for the third estate.[EG2 13] The grievances expressed in the cahiers of the various estates uniformly reject the marks of monarchical power and call for the restoration of the institutions that Labourd knew up until the 15th century,[EG2 14] including the primacy of the Basque language and other national characteristics.[Note 28]

Lower Navarre

editLower Navarre's position differs sharply from that of its neighboring provinces. The region considers itself part of the Kingdom of Navarre and, as such, believes it is not subject to the Estates General of the Kingdom of France. As a result, it does not believe it should "participate or send deputies" to the assembly.[EG2 16] This position was reaffirmed on March 16, 1789, when the assembly of the Estates of Navarre convened. On March 27, the nobility and clergy reassert the special status of Navarre, noting that "in Navarre, the kings cannot make laws without the consent and will of the three estates." With the third estate aligning itself with the position of the nobility and clergy, the Estates General of Navarre inform the king that the convocation is "irregular, illegal, and unconstitutional" as far as Navarre is concerned. Louis XVI accepted this by stating that the Navarrese "cannot be subject to the regulations made for the provinces of France."[EG2 16] Consequently, no Navarrese delegation attends the Estates General of France on May 8, nor the deliberations of the National Assembly on June 17.[EG2 17]

"Following the ordinary assembly of the General Estates of Navarre on June 15, 1789, a commission is tasked with drafting a list of grievances, the content of which can be summarized as a demand for the recognition of the independence of the Kingdom of Navarre: '[...] the rights of Navarre are based on the title given by the kings to Navarre [...] with each new reign, the oath of the kings has regenerated the Constitution and restored all the franchises and freedoms of the Navarrese [...]'.[EG2 17] The delegation that is elected does not address the General Estates of France, but the king, with the mandate to swear allegiance to him and receive his oath in return, so that '[...] the French nation may eventually give itself a constitution wise enough for Navarre to one day renounce its own and unite with France [...]'"[EG2 17]

Soule

editSoule designates its deputies with delay; the assembly is convened only on May 5, and the extraordinary assembly takes place from May 18 to July 3, 1789.[EG2 16] Just as in Labourd, the grievances focus on restoring the region's former institutions, which had been weakened by royal control, contradicting the fors. The Souletins demanded the abolition of the letters patent of June 28, 1730, which led to the near disappearance of the States of Soule, and advocated for a federative monarchy.[EG2 16]

The abolition of privileges

editBy July 1789, events accelerate. On July 9, the Constituent Assembly declared the "nullity of the limits and binding clauses of the mandates," noting that the population is engaged "by the mere presence of their deputies."[EG2 18] As a result, the deputies from Lower Navarre cannot present their arguments, for fear of violating their mandates, and it is the deputies from Labourd who unofficially represent them.

On the night of August 4, 1789, the nobility voluntarily renounced the remaining feudal rights, which were categorized as "abusive privileges." By extension, all privileges are included in this definition, encompassing the particular systems of the provinces and other arrangements often arising from bilateral treaties.[EG2 18] Article 10 of the Constitution stipulates:

A national constitution and public liberty being more advantageous to the provinces than the privileges some of them enjoyed, and the sacrifice of which is necessary for the intimate union of all parts of the empire, it is declared that all privileges of the provinces [...] are abolished without return and will remain merged into the common law of all the French.[EG2 18]

Despite the protests from the Basque provinces, voiced by their delegates, the privileges are definitively abolished, and the representativeness of Basque institutions disappears forever. Since November 11, 1789, a commission has been working on the reorganization of France into departments, and on January 12, 1790, the project for the creation of the department of Basses-Pyrénées, uniting Béarn, Soule, Lower Navarre, Labourd, and Bayonne, is presented to the Assembly.[EG2 19]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Pierre de Rosteguy de Lancre wrote in 1622: "[...] the inhabitants of this country leave their family to take that of their homes, no matter how humble they are [...] even if it were just a pigsty."[ED 1]

- ^ Pierre Hourmat laments the shortage of sources for the period from the 5th to the 10th century: "While the existence of an important military structure is attested [in Bayonne] by the remains of a castrum's towered enclosure, the seat or refuge of a cohort in the later years of the Roman Empire, the half-millennium that followed its collapse plunges us into near-total ignorance of the occupation of the castrum and the evangelization of the population. The thickest silence covers the fate of Lapurdum, and the documents we have for five centuries can be counted on one hand and lead to different or even contradictory interpretations... thus this history becomes a long series of question marks, exemplified, let us note, by that of Novempopulania."[4]

- ^ On April 12, 1215, John of England grants Bayonne legal personality, which persisted throughout the Middle Ages and, to some extent, until the French Revolution, under a commune charter similar to that of La Rochelle. According to Eugène Goyheneche, "[...] the city is governed by the Cent Pairs, which in reality are made up of a mayor, twelve aldermen, twelve councillors, and seventy-five peers who co-opt and propose each year the mayor for the king's choice. The mayor has administrative, judicial, and military powers; he holds the keys to the city, and some mayors were admirals of the Bayonne fleet. The king is represented by a prévôt."[EG2 2]

- ^ In 1673, Louis de Froidour writes to Colbert: "[...] If you were the last commoner of the province, if you own one of these houses, you are considered noble and enjoy the privileges of the nobility! Even if you are as much a gentleman as the king, if you do not own a noble house, you enjoy no prerogative, no more than the slightest peasant."[ML2 2]

- ^ Eugène Goyheneche cites, in this regard: "The wood of Sardasse near Saint-Palais, some woods and mountains in Ossès, the mills of Saint-Jean, that of Behorlegui, half of that of Béhotegui at Saint-Palais, the forges of Jaxu and the 'Reclusa' at Saint-Michel, the mines of Hosta [...], the kaiolar and pastures at Erretelia and elsewhere, the nursery of Belveder near Saint-Jean, walnut woods in Aincille, the markets of Saint-Jean, [...]."[EG2 3]

- ^ The so-called fivatières houses depended on another house, noble or free.

- ^ The albergade is the obligation to provide accommodation to a lord and his retinue in private houses. This requisition right is often converted into a monetary fee.[EG2 9]

- ^ The original term is baiulus, which during the reign of the Plantagenets corresponded to the prévôt — bayle — a high royal official delegated to the provinces of the French Crown.[ML2 4]

- ^ Lo noguer de Lixarre in 1385,[8] collection Duchesne volume CXIV, volumes 99 to 114, contains papers from Oihenart, from the former imperial library — National Library of France.

- ^ According to Eugène Goyheneche: "[...] the herds of the lord of the kayolar must stay in their pastures from July 10 to August 1. These pastures are exclusive to them day and night from June 11 to July 10; from night on July 11 to August 1: the pasture is accessible to all from August 1 to June 11 the following year."[EG2 9]

- ^ (es) "Podían tener vasallos ya que « todo infanzón que tiene una heredad libre y que con esta heredad, quiera hacer villanos o pecheros, coillazos (es decir, dar renta o porción de frutos), habrá sobre sus collazos y sobre sus villanos el mismo derecho que el rey y los grandes señores tienen sobre los suros" ([They could have vassals because 'any infanzón who has free property and who, with this property, wants to have peasants or pecheros (i.e., pay rent or part of the produce), will have the same rights over his coillazos and his peasants as the king and the great lords have over theirs).[10]

- ^ The custom of Soule distinguishes, at the bottom of the social ladder, the fivatiers (who rent houses and lands) and the botoys (sometimes owners of their house but not the land, which belongs to their lord).[12]

- ^ The donats, laypeople who dedicate themselves to Christ by taking minor vows, had to observe obedience, poverty, and chastity in the event of widowhood.

- ^ According to a consultation granted to the viscount of Macaye on February 22, 1777, by Master Durandeau of Bordeaux: "[...] on Good Friday, the lord goes to worship the Cross in the same place where the clergy perform this ceremony, and he can require that his male children enjoy the same right."[ED 2]

- ^ The court of Licharre had jurisdiction over all of Soule. Appeals were made to the court of the jurats of Dax (Landes) and from there to the sénéchal of Guyenne. The judges of the court of Licharre were the châtelain of Mauléon, the ten potestats of Soule, and the noble landowners. The custom of Soule specifies in 1520: "In the land of Soule, its potestats are the following: the lord of Domec de Lacarri, the lord of Bimeinh de Domasanh, the lord of Domec de Sibas, the lord of Olhaibi, the lord of Domec d'Ossas, the lord of Amichalgun de Charri, the lord of Genteynh, the lord of la Sala de Charrite, the lord of Espes, and the lord of Domec de Cheraute. These must come every eighteen days to the Court of Lixarre to hold court with the Captain Castellan."[8]

- ^ Poverty was very real and reported repeatedly, as in 1782 when the intendant of Guyenne, Dupré de Saint Maur, wrote to Necker: "[...] the land of Labourd borders Spain [...], half of the land is fallow, not only due to the natural sterility of the soil, which requires that three acres of heath be dedicated to fertilizer to make one acre productive, but also due to a lack of population. The main crop is corn or maize, which the inhabitants use for their food. Rarely, they harvest enough for their consumption, but the neighboring regions compensate for it. Their wine is of the poorest quality because of the proximity of the Pyrenees; they successfully cultivate apple trees, and the fruit provides a type of cider to which they add a lot of water, and this is their regular drink. The lack of pastures prevents them from raising much cattle."[ED 4]

- ^ This ratio is to be compared with other provinces at the time; in Touraine, there was one militiaman for 1,070 inhabitants, in Burgundy one for 1,300 inhabitants, but conversely, in Normandy, one for 385 inhabitants.[ED 6]

- ^ This loyalty remained constant, whether the crown was French or English, as in 1323 when Edward III of England "[recognized] the loyalty and trust he found in the inhabitants of Labourd."[ED 8]

- ^ "Acts of resistance can be found several times in the 17th century, such as the one described on July 3, 1665, by M. de Cheverry to Colbert: '...I saw the Basques in the year 1636 refuse, on the part of the King of Spain, the proposals he made to them both before and after the entry of his troops, which were such that as long as they did not take up arms and wished to remain in their homes, he would maintain them peacefully and in all their property, which at that time was of great value, due to the return of a quantity of ships loaded with cod and whales...'"[ED 9]

- ^ On June 9, 1660, Louis XIV married Marie-Thérèse of Austria in Saint-Jean-de-Luz.

- ^ Thus, in Urrugne, the subdelegate Chegaray wrote to the intendant Dupré de Saint-Maur on April 1, 1777: '...Did you call the Lord or Lady of the noble house of Urtubie... Sir, I must truthfully say that the local privileges to ensure the Community the right to appoint these jurats, in collaboration with the lord of Urtubie...'"[ED 18]

- ^ According to Maïté Lafourcade, "The text of the 1620 edict is in the National Archives: H 85 f°14. It was published by Pierre Delmas, 'Du parlement de Navarre et de ses origines,' Bordeaux, Faculty of Law, University of Bordeaux, 1898, 468 pages (BNF 30318934), p. 450-453 and by Victor Dubarat in 1920 in the Bulletin of the SSLA of Pau, p. 108-111"[ML2 8]

- ^ In 1520, according to article 3 of title 11 of the custom of Soule: "the lord of Domec de Lacarry, the lord of Bimein de Domezain, the lord of Domec de Sibas, the lord of Olhaïby, the lord of Domec d'Ossas, the lord Amichalgun of Etcharry, the lord of Gentein, the lord of the Salle de Charrite, the lord of Espès, and the lord of Domec de Chéraute."[ML 13]

- ^ The postal service of Lower Soule (Pettarra or Barhoa) includes the degairies of Laruns, Aroue, and Domezain; that of the Arbailles (Arballak) includes the Grande Arbaille and the Petite Arbaille; the postal service of Upper Soule (Basaburia) is composed of Val Dextre (ibar esküin) and Val Senestre (Ibar ester).[EG2 12]

- ^ The dégans are elected every year during the general assemblies of the parishes of each degairie by the heads of households. Their role is to ensure communication between the syndic and the parishes, to collect taxes, and to summon representatives to the Court of order. In addition to their political function, the dégans are also the guardians of Souletine archives.[EG2 7]

- ^ "The October 1620 union edict, which incorporated Béarn and Navarre into the domain of the French Crown, also decreed the union of the Chancery of Saint-Palais, the highest court of justice of Lower Navarre, with the sovereign council of Béarn to form the Parliament of Navarre seated in Pau. After many delays, this merger took place in 1624."[ML 18]

- ^ Armand Jean d'Hegoburu (or de Hégoburu), elected general syndic since January 6, 1729, by the Silviet, is himself noble and a potentate of Gentein, a noble house of Ordiarp.[ML 19]

- ^ The clergy, in particular, demands "because of the Basque language of the diocese" that the bishop of Bayonne be "chosen from among the natives of the country."[EG2 15]

References

edit- Dravasa, Étienne (1950). Les privilèges des Basques du Labourd sous l'Ancien Régime [The privileges of the Labourd Basques under the Ancien Régime] (in French). San Sebastiàn.

- ^ a b Dravasa 1950, p. 85

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 99

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 18

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 54

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 44

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 51

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 26

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 33

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 36

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 5

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 73

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 79

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 80

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 242

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 10

- ^ Dravasa 1950, pp. 414–420

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 94

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 96

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 100

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 108

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 91

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 25

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 278

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 281

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 282

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 283

- ^ Dravasa 1950, p. 303

- Bernoville, Gaëtan; Etcheverry, Michel; Veyrin, Philippe; Ithurriague, Jean (1948). Visages du Pays basque : géographie humaine du Pays basque, les institutions du Pays basque français, l'art au Pays basque, la littérature populaire basque [Faces of the Basque Country: human geography of the Basque Country, institutions of the French Basque Country, art in the Basque Country, popular Basque literature] (in French). Strasbourg: Imprimerie strasbourgeoise.

- ^ Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 51

- ^ a b c d e f Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 52

- ^ a b c d Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 53

- ^ a b c d e Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 54

- ^ a b Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 55

- ^ a b c Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 56

- ^ a b c d e Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 57

- ^ a b c d Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 61

- ^ a b Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 59

- ^ a b Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 60

- ^ a b c Bernoville et al. 1948, p. 58

- Goyheneche, Eugène (1979a). Notre terre basque [Our Basque land] (in French). Pau: Société nouvelle d'éditions régionales et de diffusion.

- ^ Goyheneche 1979a, p. 56

- ^ Goyheneche 1979a, p. 50

- ^ Goyheneche 1979a, p. 51

- Goyheneche, Eugène (1979b). Le Pays basque : Soule, Labourd, Basse-Navarre [The Basque Country: Soule, Labourd, Basse-Navarre] (in French). Pau: Société nouvelle d'éditions régionales et de diffusion.

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 152

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 160

- ^ a b c Goyheneche 1979b, p. 142

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 141

- ^ a b Goyheneche 1979b, p. 132

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 133

- ^ a b c d Goyheneche 1979b, p. 135

- ^ a b c Goyheneche 1979b, p. 134

- ^ a b c d e Goyheneche 1979b, p. 137

- ^ a b Goyheneche 1979b, p. 136

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 138

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, Map 11 in appendix

- ^ a b c Goyheneche 1979b, p. 371

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 373

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 372

- ^ a b c d Goyheneche 1979b, p. 374

- ^ a b c Goyheneche 1979b, p. 375

- ^ a b c Goyheneche 1979b, p. 376

- ^ Goyheneche 1979b, p. 380

- Lafourcade, Maïté. "Les assemblées provinciales du Pays basque français sous l'Ancien régime" [The provincial assemblies of the French Basque Country under the Ancien Régime] (PDF). euskomedia.org (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 591

- ^ a b Lafourcade, p. 599

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 589

- ^ a b Lafourcade, p. 593

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 594

- ^ a b Lafourcade, p. 597

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 598

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 608

- ^ a b Lafourcade, p. 609

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 610

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 600

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 606

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 601

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 602

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 603

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 604

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 615

- ^ Lafourcade, p. 616

- ^ a b c d Lafourcade, p. 607

- Lafourcade, Maïté (2011). La société basque traditionnelle [Traditional Basque society]. Terre et gens (in French). Donostia et Bayonne, Elkar. ISBN 978-84-15337-11-9.

- ^ Lafourcade 2011, p. 9

- ^ Lafourcade 2011, p. 41

- ^ a b Lafourcade 2011, p. 29

- ^ Lafourcade 2011, p. 28

- ^ Lafourcade 2011, p. 39

- ^ a b c Lafourcade 2011, p. 12

- ^ a b c Lafourcade 2011, p. 13

- ^ Lafourcade 2011, p. 10

Other sources

edit- ^ Abizu, Danielle; Antz, Jacques; Audenot, Nelly (1994). Sare (in French). Vol. 2. Saint-Jean-de-Luz: Ekaïna. p. 181. ISBN 2-9507270-2-6.

- ^ Lafourcade, Maïté (1989). Le droit coutumier [Customary law]. Euskal Herriak - Pays basque 2/Langue, culture, identité (in French). Les cahiers de l'I.F.O.R.E.P. n° 57. pp. 38–57.

- ^ "La stèle romaine d'Hasparren" [The Roman stele at Hasparren]. Notice no PM64000184, on the open heritage platform, Palissy database, French Ministry of Culture (in French). Archived from the original on February 4, 2024.

- ^ Hourmat, Pierre (1986). Histoire de Bayonne des origines à la révolution française de 1789 [History of Bayonne from its origins to the French Revolution of 1789] (in French). Bayonne: Société des sciences, lettres et arts de Bayonne. pp. 27–35.

- ^ Hourmat, Pierre (1989). Visiter Bayonne [Visit Bayonne] (in French). Bordeaux: Sud Ouest. p. 6. ISBN 978-2-905983-72-5.

- ^ Lafourcade, Maïté (2001). La féodalité en Labourd : enquête ordonnée par Édouard II d'Angleterre pour connaître ses droits sur cette terre - 1311 [Feudalism in Labourd: inquiry ordered by Edward II of England into his rights to the land - 1311] (in French). Saint-Sébastien: Basque Studies Society. pp. 165–180.

- ^ Destrée, Alain (1954). La Basse-Navarre et ses institutions de 1620 à la Révolution [Basse-Navarre and its institutions from 1620 to the Revolution] (in French). Paris: Thèse de droit.

- ^ a b Raymond, Paul (1863). Dictionnaire topographique du département des Basses-Pyrénées [Topographical dictionary of the Basses-Pyrénées department] (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Impériale. p. 102. Archived from the original on December 3, 2024.

- ^ Nussy-Saint-Saëns, Marcel (1955). Le païs de Soule : essai sur la coutume basque [Le païs de Soule: an essay on Basque custom] (in French). Bordeaux: Cledes et Fils Imprimeurs Éditeurs. quoted by Goyheneche, Eugène (1979). Le Pays basque : Soule, Labourd, Basse-Navarre [The Basque Country: Soule, Labourd, Basse-Navarre] (in French). Pau: Société nouvelle d'éditions régionales et de diffusion. p. 137.

- ^ "Les Coillazos de Navarre" [Coillazos from Navarre]. euskaletexea2013.blogspot.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "II". Fuero General [General Jurisdiction] (in French). Vol. III. p. 17.

- ^ "La coutume de Soule" [Soule custom]. Montory commune website (in French). Archived from the original on April 20, 2024. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Mousnier, Roland (2005). Les institutions de la France sous la monarchie absolue : 1598-1789 [French institutions under the absolute monarchy: 1598-1789] (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-054836-9.

- ^ Barbiche, Bernard (1999). Les institutions de la monarchie française à l'époque moderne, XVIe – XVIIIe siècle [The institutions of the French monarchy in the modern era, 16th - 18th centuries] (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-048195-7.

- ^ Webster, Wentworth (1901). Les loisirs d'un étranger au Pays basque [A foreigner's leisure time in the Basque Country] (in French). Chalon-sur-Saône: imprimerie de E. Bertrand. p. 18.

- ^ Petit-Dutaillis, Charles (1933). La monarchie féodale en France et en Angleterre, Xe – XIIIe siècle [Feudal monarchy in France and England, 10th- 13th centuries] (in French). Paris: la Renaissance du livre. p. 175.

- ^ Extract from Registres français, tome 1, page 140. The Bayonne archives are grouped into two collections, one named Registres gascons and the other Registres français.

- ^ Raymond, Paul. Introduction à l'inventaire de la série C des archives des Pyrénées-Atlantiques [Introduction to the inventory of series C of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques archives] (in French). p. 91.

- ^ Veyrin, Philippe (1975). Les Basques : de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse-Navarre, leur histoire et leurs traditions [The Basques: from Labourd, Soule and Basse-Navarre, their history and traditions] (in French). Grenoble: Arthaud. p. 157. ISBN 2-7003-0038-6.

- ^ Etcheverry, Michel (1931). Gure Herria (in French). Bayonne. p. 392.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Destrée, Alain (1954). La Basse Navarre et ses institutions de 1620 à la Révolution [Lower Navarre and its institutions from 1620 to the Revolution] (in French). Paris: Thèse de droit. p. 180.