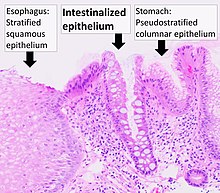

Intestinal metaplasia is the transformation (metaplasia) of epithelium (usually of the stomach or the esophagus) into a type of epithelium resembling that found in the intestine. In the esophagus, this is called Barrett's esophagus. Chronic inflammation caused by H. pylori infection in the stomach and GERD in the esophagus are seen as the primary instigators of metaplasia and subsequent adenocarcinoma formation. Initially, the transformed epithelium resembles the small intestine lining; in the later stages it resembles the lining of the colon. It is characterized by the appearance of goblet cells and expression of intestinal cell markers such as the transcription factor, CDX2.

| Intestinal metaplasia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Histopathology of Barrett's esophagus, showing intestinalized epithelium with Goblet cells, as opposed to normal stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus, and pseudostratified columnar epithelium of the fundus of the stomach. H&E stain. |

Although H. pylori infection can cause gastrointestinal metaplasia, its eradication does not reverse the process.[1] Bile reflux is an additional pathogenic factor in gastrointestinal metaplasia that can continuously irritate the gastric mucosa. Bile acids in refluxed fluid are widely reported to be associated with gastrointesinal metaplasia.[1][2]

Risk factors

editAlthough it was originally reported that people of East Asian ethnicity with gastric intestinal metaplasia are at increased risk of stomach cancer,[3] it is now clear that gastric intestinal metaplasia is also a risk factor in low-incidence regions like Europe.[4] Risk factors for progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia to full blown cancer are smoking and family history.[5]

Latency

editIntestinal metaplasia lesions that have an active DNA damage response are likely to experience extended latency in the premalignant state until the incidence of damages overrides the DNA damage response leading to clonal expansion and progression to cancer.[6] During the DNA damage response, proteins are expressed that detect DNA damages and activate downstream responses like DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints or apoptosis.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b Qu X, Shi Y (July 2022). "Bile reflux and bile acids in the progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia". Chin Med J (Engl). 135 (14): 1664–1672. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000002290. PMC 9509189. PMID 35940882.

- ^ Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Payne CM, Dvorak K (July 2009). "Bile acids as endogenous etiologic agents in gastrointestinal cancer". World J Gastroenterol. 15 (27): 3329–40. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.3329. PMC 2712893. PMID 19610133.

- ^ Choi, AY; Strate, LL; Fix, MC; Schmidt, RA; Ende, AR; Yeh, MM; Inadomi, JM; Hwang, JH (April 2018). "Association of gastric intestinal metaplasia and East Asian ethnicity with the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in a U.S. population". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 87 (4): 1023–1028. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2017.11.010. PMID 29155082.

- ^ den Hollander WJ, Holster IL, den Hoed CM, Capelle LG, Tang TJ, Anten MP, Prytz-Berset I, Witteman EM, Ter Borg F, Hartog GD, Bruno MJ, Peppelenbosch MP, Lesterhuis W, Doukas M, Kuipers EJ, Spaander MC (April 2019). "Surveillance of premalignant gastric lesions: a multicentre prospective cohort study from low incidence regions". Gut. 68 (4): 585–593. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314498. PMID 29875257. S2CID 46962160.

- ^ Nieuwenburg SA, Mommersteeg MC, Eikenboom EL, Yu B, den Hollander WJ, Holster IL, den Hoed CM, Capelle LG, Tang TJ, Anten MP, Prytz-Berset I, Witteman EM, Ter Borg F, Burger JP, Bruno MJ, Fuhler GM, Peppelenbosch MP, Doukas M, Kuipers EJ, Spaander MC (March 2021). "Surveillance of premalignant gastric lesions: a multicentre prospective cohort study from low incidence regions". Endosc Int Open. 9 (3): E297–E305. doi:10.1055/a-1314-6626. PMC 7892268. PMID 33655025.

- ^ a b Krishnan, V; Lim, DXE; Hoang, PM; et al. (October 2020). "DNA damage signalling as an anti-cancer barrier in gastric intestinal metaplasia". Gut. 69 (10): 1738–1749. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319002. PMC 7497583. PMID 31937549.