Ipswich is a coastal town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 13,785 at the 2020 census.[1] Home to Willowdale State Forest and Sandy Point State Reservation, Ipswich includes the southern part of Plum Island. A residential community with a vibrant tourism industry, the town is famous for its clams, celebrated annually at the Ipswich Chowderfest, and for Crane Beach, a barrier beach near the Crane estate. Ipswich was incorporated as a town in 1634.

Ipswich, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

| Town of Ipswich | |

John Whipple House, constructed c. 1677 | |

| Nickname: Birthplace of American Independence | |

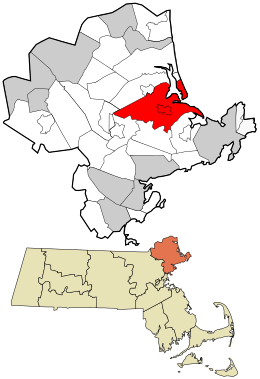

Location in Essex County and the state of Massachusetts. | |

| Coordinates: 42°40′45″N 70°50′30″W / 42.67917°N 70.84167°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Essex |

| Settled | 1633 |

| Incorporated | August 5, 1634 |

| Founded by | John Winthrop the Younger |

| Named for | Ipswich, England |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| Area | |

• Total | 42.5 sq mi (110.1 km2) |

| • Land | 32.1 sq mi (83.2 km2) |

| • Water | 10.4 sq mi (26.9 km2) |

| Elevation | 50 ft (15 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 13,785 |

| • Density | 320/sq mi (130/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 01938 |

| Area code | 351/356/978 |

| FIPS code | 25-32310 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0619448 |

| Website | www |

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

Ipswich was founded by John Winthrop the Younger, son of John Winthrop, one of the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 and its first governor, elected in England in 1629. Several hundred colonists sailed from England in 1630 in a fleet of 11 ships, including Winthrop's flagship, the Arbella. Investigating the region of Salem and Cape Ann, they entertained aboard the Arbella for a day, June 12, 1630, a native chief of the lands to the north, Chief Masconomet.[2] The event was recorded in Winthrop's journal on the 13th, but Winthrop did not say how they overcame the language barrier. The name they heard from Masconomet concerning the country over which he ruled has been reconstructed as Wonnesquamsauke, which the English rendered as "Agawam". The colonists, however, sailed to the south where some buildings had already been prepared for them at a place newly named Charlestown.

That winter they lost a few hundred colonists to malnutrition and disease. They also experienced their first nor'easter, which cost them some fingers and toes, as well as houses destroyed by the fires they kept burning day and night. Just as Winthrop was handing out the last handful of grain, the supply ship Lyon entered Boston Harbor. John sent for his family in England, but his then wife, Margaret, her children, and his eldest son, John, whose mother was the elder John's first wife, Mary Forth, did not arrive until November, on the Lyon.

John the Younger resided with his father and stepmother until 1633, when he resolved to settle in Agawam, with the permission of the General Court of Massachusetts. Captain John Smith had written about the Angoam or Aggawom region in 1614, calling it "an excellent habitation, being a good and safe harbour."[3]

John the Younger and 12 men aboard a shallop sailed into Ipswich harbor and took up residence there. The first settlers with Winthrop were William Clerk, Robert Coles, Thomas Howlet, John Biggs, John Gage, Thomas Hardy, William Perkins, John Thorndike, William Sargent, and three others whose names are uncertain.[4][5] Two men continued up the river (now River Road) to a large meadow, which they called New Meadows, now Topsfield. Agawam was incorporated on August 5, 1634,[6] as Ipswich, after Ipswich in the county of Suffolk, England. The name "Ipswich" was taken "in acknowledgment of the great honor and kindness done to our people which took shipping there."[7] Nathaniel Ward, an assistant pastor in town from 1634 to 1636, wrote the first code of laws for Massachusetts and later published the religious/political work The Simple Cobbler of Aggawam in America[8] in England.

In 1638, Masconomet entered into a contract with John Winthrop the Younger for the purchase of Ipswich for "wampampeage, & other things: and ... also for the sume [sic] of twenty pounds."[9] There is no record of any Native resistance to the colonization either at Charlestown or at Agawam, though there is documentation of devastating virgin soil epidemics among indigenous people in the area around 1617 and again in 1633, and contemporary reports attest to ghost towns encountered by early English settlers.[10]

Pioneers became farmers, fishermen, shipbuilders or traders. The tidal Ipswich River provided water power for mills, and salt marshes supplied hay for livestock. But in 1687, Ipswich residents, led by the Reverend John Wise, protested a tax imposed by the governor, Sir Edmund Andros. As Englishmen, they argued, taxation without representation was unacceptable. Citizens were jailed, but then Andros was recalled to England in 1689, and the new British sovereigns, William III and Mary II, issued colonists another charter. The rebellion is the reason the town calls itself the "Birthplace of American Independence".[11]

A cottage industry in lace-making developed. Ipswich Lace is a unique style, and the only known hand-made bobbin lace produced commercially in the U.S.[12]

Great clipper ships of the 19th century bypassed Ipswich in favor of the deep-water seaports at Salem, Newburyport, Quincy, and Boston. The town remained primarily a fishing and farming community, its residents living in older homes they could not afford to replace—leaving Ipswich with a considerable inventory of early architecture. In 1822, a stocking manufacturing machine that had been smuggled out of England arrived at Ipswich, violating a British ban on exporting such technology, and the community developed as a mill town. In 1828, the Ipswich Female Seminary was founded. In 1868, Amos A. Lawrence established the Ipswich Hosiery Mills beside the river. It became the nation's largest stocking mill by the turn of the 20th century. In 1913, the mill experienced a labor strike led by the Industrial Workers of the World. What may be the last witchcraft trial in North America was held in Ipswich in 1878. In the Ipswich witchcraft trial, a member of the Christian Science religion was accused of using his mental powers to harm others, including a spinster living in the town.[13]

In 1910, Richard T. Crane Jr. of Chicago, the business magnate owner of Crane Plumbing, bought Castle Hill, a drumlin on Ipswich Bay. He hired Olmsted Brothers, successors to Frederick Law Olmsted, to landscape his 3,500-acre (14 km2) estate, and engaged the Boston architectural firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge to design an Italian Renaissance-Revival style villa on the summit. A grande allée, 160 feet (49 m) wide and lined with statuary, would run the half mile from house to sea. But his wife, Florence, loathed the building. Crane promised that if she still disliked it in 10 years, he would replace it. In 1928, a new 59-room mansion designed by Chicago architect David Adler in the English Stuart style stood in its place, called the Great House. At Mrs. Crane's death in 1949, the entire property was bequeathed to The Trustees of Reservations, which uses it as a venue for concerts and weddings.[14]

The town government was reformed in 1950 with the acceptance of the Town Manager Charter. This charter was rescinded by the voters, regained, and lost again. Voters adopted the present Town Manager-Selectmen Charter in 1967. In 2012 Ipswich hired its first female Town Manager, Robin Crosbie, who served until her retirement in 2018.

Geography

editIpswich is drained by the Ipswich River and Plum Island Sound, which join at their mouths and empty through a narrow but navigable channel at the foot of Castle Hill around Sandy Point into Ipswich Bay adjoining the Atlantic Ocean. The crane estate has a long lawn that overlooks the bay and often has castle hill concerts. The southern part of Plum Island falls within the area allotted to the town, making up the town's ocean shore along with Castle Neck, south of the Sound. The northeastern part of town is marshy, where the Rowley River, Roger Island River, and Eagle Hill River drain into Plum Island Sound. South of Castle Neck, the Castle Neck River separates the town from neighboring Essex.

Much of the western end of town is dominated by Willowdale State Forest, and other parts of the town are also protected land, including Crane Wildlife Refuge on Castle Neck, the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge and Sandy Point State Reservation on Plum Island, Hamlin Reservation, Heartbreak Hill Reservation, Bull Brook Reservoir, Greenwood Farm, and part of Appleton Farms Sanctuary, which extends into Hamilton.

Ipswich is in central Essex County and is 11 miles (18 km) south of Newburyport, 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Gloucester, 13 miles (21 km) north of Salem, 20 miles (32 km) east of Lawrence, and 28 miles (45 km) northeast of Boston. It is bordered by Rowley to the north, Boxford to the west, and Topsfield, Hamilton, Essex and Gloucester to the south. (The border with Gloucester lies across Essex Bay, and as such there is no land connection between the two.)

Transportation

editThere is no interstate highway through Ipswich; Interstate 95 passes through neighboring Boxford and Topsfield. U.S. Route 1, known as the Newburyport Turnpike, passes through the western end of town. Massachusetts Route 1A and Route 133 pass through the town, entering concurrently from Rowley and passing through the center of town before splitting south of the town center; Route 1A heads towards Hamilton and Beverly, while Route 133 leads to Essex and Gloucester.

Ipswich has a station along the Newburyport/Rockport Line of the MBTA Commuter Rail, providing service between Newburyport and Boston's North Station. There is no air service in town; the nearest small airports are in Newbury and Beverly, and the nearest national service is Boston's Logan International Airport. The Ipswich Essex Explorer provides summertime weekend shuttle service connecting Ipswich MBTA train station with Crane Beach, Essex and Appleton Farms.

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 4,562 | — |

| 1800 | 3,305 | −27.6% |

| 1810 | 3,569 | +8.0% |

| 1820 | 2,553 | −28.5% |

| 1830 | 2,949 | +15.5% |

| 1840 | 3,000 | +1.7% |

| 1850 | 3,349 | +11.6% |

| 1860 | 3,300 | −1.5% |

| 1870 | 3,720 | +12.7% |

| 1880 | 3,699 | −0.6% |

| 1890 | 4,439 | +20.0% |

| 1900 | 4,658 | +4.9% |

| 1910 | 5,777 | +24.0% |

| 1920 | 6,201 | +7.3% |

| 1930 | 5,599 | −9.7% |

| 1940 | 6,348 | +13.4% |

| 1950 | 6,895 | +8.6% |

| 1960 | 8,544 | +23.9% |

| 1970 | 10,750 | +25.8% |

| 1980 | 11,158 | +3.8% |

| 1990 | 11,873 | +6.4% |

| 2000 | 12,987 | +9.4% |

| 2010 | 13,175 | +1.4% |

| 2020 | 13,785 | +4.6% |

| 2023* | 13,903 | +0.9% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] | ||

As of the census of 2000, there were 12,987 people, 5,290 households, and 3,459 families residing in the town.[note 1] The population density was 398.6 inhabitants per square mile (153.9/km2). There were 5,601 housing units at an average density of 66.4 persons/km2 (171.9 persons/sq mi). The racial makeup of the town was 97.60% White, 0.39% African American, 0.08% Native American, 0.80% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.33% from other races, and 0.79% from two or more races. 1.04% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 5,290 households, out of which 30.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.0% were married couples living together, 8.4% have a woman whose husband does not live with her, and 34.6% were non-families. 28.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.00.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 23.0% under the age of 18, 5.1% from 18 to 24, 28.3% from 25 to 44, 28.1% from 45 to 64, and 15.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.2 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $57,284, and the median income for a family was $74,931. Males had a median income of $51,408 versus $38,476 for females. The per capita income for the town was $32,516. 7.1% of the population and 4.1% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total people living in poverty, 7.8% are under the age of 18 and 13.0% are 65 or older.

Government

edit| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third parties | Total Votes | Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 65.25% 6,273 | 32.34% 3,109 | 2.41% 232 | 9,614 | 32.91% |

| 2016 | 57.74% 4,939 | 35.22% 3,013 | 7.04% 602 | 8,554 | 22.52% |

| 2012 | 53.33% 4,464 | 44.89% 3,758 | 1.78% 149 | 8,371 | 8.43% |

| 2008 | 56.55% 4,573 | 41.81% 3,381 | 1.64% 133 | 8,087 | 14.74% |

| 2004 | 55.14% 4,281 | 43.23% 3,356 | 1.64% 127 | 7,764 | 11.91% |

| 2000 | 50.14% 3,548 | 40.69% 2,879 | 9.17% 649 | 7,076 | 9.45% |

| 1996 | 54.83% 3,757 | 34.43% 2,359 | 10.74% 736 | 6,852 | 20.40% |

| 1992 | 40.36% 2,862 | 35.45% 2,514 | 24.20% 1,716 | 7,092 | 4.91% |

| 1988 | 46.05% 2,946 | 52.13% 3,335 | 1.81% 116 | 6,397 | 6.08% |

| 1984 | 38.47% 2,358 | 60.96% 3,736 | 0.57% 35 | 6,129 | 22.48% |

| 1980 | 32.95% 1,960 | 45.44% 2,703 | 21.62% 1,286 | 5,949 | 12.49% |

| 1976 | 45.46% 2,685 | 51.35% 3,033 | 3.18% 188 | 5,906 | 5.89% |

| 1972 | 43.46% 2,437 | 56.07% 3,144 | 0.46% 26 | 5,607 | 12.61% |

| 1968 | 49.27% 2,383 | 47.88% 2,316 | 2.85% 138 | 4,837 | 1.39% |

| 1964 | 65.67% 2,978 | 34.05% 1,544 | 0.29% 13 | 4,535 | 31.62% |

| 1960 | 43.41% 2,017 | 56.50% 2,625 | 0.09% 4 | 4,646 | 13.09% |

| 1956 | 29.07% 1,162 | 70.80% 2,830 | 0.13% 5 | 3,997 | 41.73% |

| 1952 | 36.91% 1,429 | 62.99% 2,439 | 0.10% 4 | 3,872 | 26.08% |

| 1948 | 43.64% 1,433 | 55.33% 1,817 | 1.04% 34 | 3,284 | 11.69% |

| 1944 | 44.35% 1,283 | 55.38% 1,602 | 0.28% 8 | 2,893 | 11.03% |

| 1940 | 40.55% 1,191 | 59.07% 1,735 | 0.37% 11 | 2,937 | 18.52% |

Education

editThe first Ipswich Grammar School began around 1636.[27]

Elementary schools

editPaul F. Doyon Memorial and Winthrop are the town's two elementary schools. Paul F. Doyon is on Linebrook Road and was originally named the Linebrook School, until it was renamed in 1967 after its namesake died in the Vietnam War.[28] Grade levels end in fifth grade, after which students move to Ipswich Middle School.

Middle and high schools

editThe middle school and high school are in the same building and share the library, the cafeteria, performing arts facilities and athletic resources (tennis courts, a baseball diamond, a football field, and a running track).

Ipswich Middle School (IMS) covers grades 6–8, with each grade assigned to a "pod", a common area with a projector with lockers and classrooms for the grade branching off the pod.

Ipswich High School (IHS) has been considered one of the best public high schools in the Boston area.[citation needed] The Ipswich Public Schools also have what is considered one of the best performing arts programs. In 2005, the high school was named a "Blue Ribbon" school. The Blue Ribbon is an award for national excellence in education under the No Child Left Behind legislation. The school also received a Vanguard award for similar academic prowess. IHS offers college-prep, honors, and AP-level classes. It has one of Massachusetts's highest graduation rates.

Ipswich Middle/High School is considered to have one of the state's best music programs.[citation needed] It offers dance, choruses, bands (including jazz, pep and concert bands), orchestra and symphony orchestra.

The high school mascot is the Tiger, and the school colors are orange and black. Ipswich competes in the Cape Ann League. The high school football team won the Division 3A Super Bowl Championship in 2006. It was the school's first title since 1992, and the fifth in school history. (Previous titles were achieved in 1974, 1977, 1991, and 1992.) Ipswich's traditional rival is Hamilton-Wenham Regional High School. The Ipswich Volleyball Team has won the Division IV State Championship in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

Points of interest

edit- Appleton Farms (1638)

- Brown Stocking Mill Historic District

- Castle Hill (1928)

- Choate Bridge (1764)

- Crane Beach

- John Heard House/Ipswich Historical Society (c. 1800)

- John Whipple House (1642/1677)

- South Green Historic District

Notable people

edit- James Appleton, 19th century politician and activist

- Dick Berggren, motorsports announcer and magazine editor

- Charles E. Bohlen, U.S. diplomat

- Anne Bradstreet, poet

- Simon Bradstreet, governor

- Michael Burns, actor, historian, professor emeritus at Mount Holyoke College, former resident of Ipswich

- Rufus Choate, lawyer, orator and politician

- Eunice Caldwell Cowles, educator

- Nathan Dane, lawyer

- Arthur Wesley Dow, artist

- John F. Dolan, legislator and conservation advocate

- Thomas Dudley, governor

- Dennis Eckersley, baseball Hall-of-Fame pitcher

- Ed Emberley, artist of children's drawing books

- Melissa Ferrick, musician

- David Giddings, Wisconsin Territorial legislator, engineer, and businessman

- Sarah Whipple Goodhue, 17th-century writer

- Mark Harris, Maine politician

- Elizabeth Topham Kennan, former president of Mount Holyoke College and wife of actor-historian Michael Burns, former resident of Ipswich

- Stuffy McInnis, baseball player and manager

- Jimmy McLane, swimmer, Olympic champion

- John Norton, author, minister at Ipswich 1636

- John Proctor, victim of the Salem witch trials

- Richard S. Rust, abolitionist and educator

- Jenny Slew, one of the first black Americans to sue for her freedom, and the first person to succeed through trial by jury

- Eric Standley, contemporary artist

- John Updike, author

- Nathaniel Ward, clergyman and jurist

Notes

edit- ^ This article describes the town of Ipswich as a whole. Additional demographic detail is available which describes only the more densely populated central settlement or village within the town, although that detail is included in the aggregate values reported here. See: Ipswich (CDP), Massachusetts

References

edit- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Ipswich town, Essex County, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ Prince, John (1888), Hurd, D. Hamilton (ed.), "Essex", History of Essex County, Massachusetts: with Biographical Sketches of Many of its Pioneers and Prominent Men, vol. II, Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis & Co, p. 1155

- ^ Smith, John (1837). A description of New England; or, The observations, and discoveries of Captain Iohn Smith (admirall of that country) in the north of America, in the year of our Lord 1614; with the successe of sixe ships, that went the next yeare 1615; and the accidents befell him among the French men of warre: with the proofe of the present benefit this countrey affoords; whither this present yeare, 1616, eight voluntary ships are gone to make further tryall. Washington: P. Force.

- ^ Vannah, Alison I. (1999). "Crotchets of Division":Ipswich in New England, 1633-1679 (PDF). Brandeis University. pp. 28–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-10-05. Retrieved 2022-04-07.

- ^ Waters, Thomas Franklin; Ipswich Historical Society; Goodhue, Sarah; Wise, John (1905). Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony . Ipswich, Mass., The Ipswich historical society. p. 10.

- ^ Records of the governor and company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England, Volume 1, accessed March 15, 2011.

- ^ Winthrop, John. Journal of John Winthrop: 1630–1649, accessed March 15, 2011.

- ^ Ward, Nathaniel. The Simple Cobbler of Aggawam in American

- ^ Perley, Sidney (1912). The Indian land titles of Essex County, Massachusetts. The Library of Congress. Salem, Mass. : Essex Book and Print Club.

- ^ Bradford, William; Winslow, Edward; Dexter, Henry Martyn (1865). Mourt's relation or journal of the plantation at Plymouth. Harvard University. Boston, J. K. Wiggin.

- ^ Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1490572741.

- ^ Raffel, Marta Cotterell (2003). The laces of Ipswich: the art and economics of an early American industry, 1750-1840. Hannover: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-58465-163-5.

- ^ Jastrow, Joseph. The Psychology of Conviction. Reprint ed. Charleston, S.C.: BiblioLife, 2009, p. 200; Springer, Fleta Campbell. According to the Flesh: A Biography of Mary Baker Eddy. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1930, p. 238-240.

- ^ Salny, Stephen M. (2001). The Country Houses of David Adler, pp. 63-71. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-73045-X.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020−2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "Election Results".

- ^ Massachusetts Board of Education; George A. Walton (1877), "Report on Academies: Ipswich Grammar School", Annual Report...1875-76, Boston – via Internet Archive

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Paul Doyon". Fallen Heroes Project. 13 October 2010. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

External links

edit- Town of Ipswich official website

- Ipswich Historical Commission and Visitor Center website, HistoricIpswich.net

- Ipswich Public Library

- Willowdale State Forest

- Ipswich Arts and Cultural Council

- History of Ipswich, Essex, and Hamilton by Joseph Barlow Felt published 1834. Online at books.google.com

- Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Vol.2 1700–1917 by Thomas Franklin Waters, Sarah Goodhue, John Wise. Published 1917.

- Memorial of Samuel Appleton of Ipswich, Massachusetts by Isaac Appleton Jewett, published 1850.

- 1795 Map of Ipswich, Massachusetts Click on the screen size maps to get a much larger image.

- 1832 Map of Ipswich, Massachusetts by Philander Anderson.

- 1872 Map of Ipswich plate 66–67 in the 1872 Atlas of Essex County, Massachusetts.

- 1872 Map of Ipswich Center plate 69 in the 1872 Atlas of Essex County, Massachusetts.

- Old USGS maps of Ipswich Archived 2009-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

- The Birthplace of American Independence, 1687, How Ipswich, Massachusetts, Won This Inscription for Its Town Seal, National Historical Society