Nathaniel Ward (1578 – October 1652) was a Puritan clergyman and pamphleteer in England and Massachusetts.

Nathaniel Ward | |

|---|---|

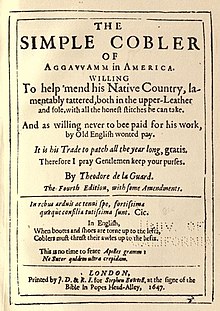

Title page of Ward's book The Simple Cobler of Aggawamm in America (4th ed., 1647) | |

| Born | 1578 |

| Died | October 1652 (aged 73–74) |

| Alma mater | Emmanuel College, Cambridge |

| Occupations |

|

| Church | Protestant (Puritan) |

| Writings | Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) |

| Signature | |

Biography

editA son of John Ward, a noted Puritan minister, he was born in Haverhill, Suffolk, England. He studied law and graduated from Emmanuel College, Cambridge University in 1603.[1][2] He practised as a barrister and travelled in continental Europe. In Heidelberg he met a German Protestant reformer, David Pareus, who persuaded him to enter the ministry. In 1618 he was a chaplain to a company of English merchants at Elbing, in Poland. He returned to England and in 1628 he was appointed rector of Stondon Massey in Essex. He was soon recognised as one of the foremost Puritan ministers in Essex, and so in 1631 was reprimanded by the Bishop of London, William Laud. Although he escaped excommunication, in 1633 he was dismissed for his Puritan beliefs. (Ward's two brothers also suffered for their non-conformity.)

In 1634 Ward emigrated to Massachusetts and became a minister in Ipswich for two years. He then resigned because of ill-health. While still living in Ipswich, he wrote for the colony of Massachusetts The Body of Liberties, legal code, which was adopted by the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Company in December 1641. This was the first code of laws established in New England. The Body of Liberties defined liberty in terms that were advanced in their day, establishing a code of fundamental principles based on Common Law, Magna Carta, and the Old Testament. However, Ward believed in theocracy rather than democracy. One of his epigrams was:

The upper world shall Rule,

While Stars will run their race:

The nether world obey,

While People keep their place.

Ward thought that justice and the law were essential to the liberty of the individual. Some have said that The Body of Liberties began the American tradition of liberty, leading eventually to the United States Constitution.[3]

In 1645 Ward began his second book, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America. This was published in England in January, 1646–1647, before Ward's return there, under the pseudonym of Theodore de la Guard. Three other editions, with important additions and changes, soon followed. The Simple Cobbler is a small book, which "in spite of its bitterness, and its lack of toleration" is "full of quaint originality, grim humor and power", according to the anthology Colonial Prose and Poetry: The Transplanting of Culture 1607–1650 (1903).[4]

According to the anthology, the book is "probably the most interesting literary performance" in the first half of the 17th century in the English colonies that later became the United States. The book was later reprinted in 1713 and 1843 in Boston, Massachusetts.[4]

He also wrote several religious-political pamphlets.

At the end of the English Civil War, Ward returned to England, where he wrote pamphlets, particularly Discolliminium (1650), critical of the establishment of the Commonwealth of England. His contribution to the Engagement debate (an oath of loyalty to the new Commonwealth) and his attack on polemic opponents, particularly John Dury, included attacking the speed with which the oath was to be administered and questioning the government's legitimacy as a just power. Ward became the minister of the church at Shenfield in Essex and died shortly after in Shenfield.

References

edit- ^ Tyler, Moses Coit, A History of American Literature, 1607–1676. G.P. Putnam's Sons (1878), p. 228.

- ^ "Ward, Nathaniel (WRT596N)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Winthrop Society

- ^ a b Trent, William P. and Wells, Benjamin W., Colonial Prose and Poetry: The Transplanting of Culture 1607–1650, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1903 edition, pp. 250–251.

External links

edit- Works by Nathaniel Ward at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Nathaniel Ward at the Internet Archive

- Cambridge History of English and American Literature – Emigrant Puritans

- "Ward, Nathaniel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28700. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.). The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. 1885–1900.