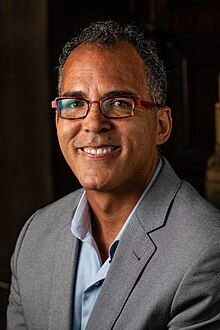

James Forman Jr. (born James Robert Lumumba Forman; June 22, 1967)[2] is an American legal scholar currently on leave from serving as the J. Skelly Wright Professor of Law at Yale Law School. He is the author of Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America, which won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction, and a co-founder of the Maya Angelou School in Washington, D.C.

James Forman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | James Robert Lumumba Forman June 22, 1967 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Education | Brown University (BA) Yale University (JD) |

| Notable work | Locking Up Our Own (2017) |

| Spouse |

Ify Nwokoye (m. 2005) |

| Children | 1 |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Constitutional law |

| Institutions | |

In 2023, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[3]

Early life

editForman is the son of James Forman Sr. and Constancia Romilly, who met through their activism and involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC.[4] Forman Sr. was the group's executive secretary handling internal operations[5] from 1961 to 1966 and active during the 1964 Freedom Summer.[4] Romilly, daughter of the British aristocrats Jessica Mitford and Esmond Romilly,[4] dropped out of Sarah Lawrence College to join the group in 1962 and would eventually become a coordinator of SNCC's Atlanta chapter.[5] Forman has a brother, Chaka Forman.[6] In the early 1970s, when Forman was seven years old, his parents, who had never been married, separated.[4][7] Forman speculated in an interview that FBI pressure on civil rights groups at the time contributed to the strain on his parents' relationship:[4] "There was also the period when...the FBI was putting incredible pressure on civil rights groups through the counter-intelligence program -- or the COINTELPRO program. And they were fomenting lies and distrust... They [Forman Sr. and Romilly] had a hard time in those years for a lot of reasons but I know, for my mom in particular, that that was one."[4]

After his parents' separation, Forman and his brother lived with Romilly in New York but spent summers and holidays with Forman Sr., and Forman has stated that both parents were active in his life.[4]

Forman was accepted into an elite New York high school: Hunter College High School.[4] The school was almost all white, prompting Romilly to move with her sons to Atlanta so they could grow up in a black community, which she considered important for their racial identities.[4] Forman expressed the importance of this move in an interview, saying: "In a city that has so many African-American people, I would go to school, and the jocks were black. The nerds were black... The artsy kids were black. The band-camp kids were black. The thugs were black -- like, everybody was black. So there wasn't a way to perform that went along with being black. And that, I think, was very powerful and liberating for me as a child because it meant I got to be who I was, which was a nerdy kid. And nobody thought, oh, well, you're not black if you're reading books."[4]

Forman attended Roosevelt High School in Atlanta.[8] He went on to attend Brown University, from which he received his Bachelor of Arts in 1988.[9] He received a Juris Doctor degree from Yale Law School in 1992.[9]

Law career

editLaw clerk

editIn the 1990s, right after graduating law school, Forman began work as a law clerk for William Norris of the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.[4] The next year he clerked for Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.[4]

Forman describes working with O'Connor as enjoyable, although they disagreed on many of the social issues that came before the court.[4] In his interview for the job, Forman was asked how his differing political viewpoints would affect his work as a law clerk.[4] In an interview, he stated his response: "I told her that I will argue with you. I'll tell you the truth about what I think. I will try to persuade you. But at the end of the day, you are the justice, and I'm the law clerk. And if I'm taking this job, I'm agreeing to help you do your work, right? I'm helping -- if you decide to come out the other way and assign me the opinion, then I'll write the best opinion I can for you."[4]

Public defender

editDuring Forman's stint as O'Connor's clerk, the justice encouraged him to pursue a career in the Department of Justice or with a civil rights organization such as the NAACP.[10] He instead chose to become a public defender, saying in an interview, "I imagined myself doing the civil rights work of my generation."[9]

Forman became a public defender in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1994, a job he would hold for six years.[11] He wrote about some of his experiences with clients in Locking Up Our Own.

Teaching

editIn 2003, Forman began teaching law at Georgetown University.[8] He remained at Georgetown until 2011, when he joined the faculty at Yale.[8] There he teaches Constitutional Law and seminars entitled Race, Class and Punishment, and Inside Out: Issues in Criminal Justice.[8] Forman's Inside Out course meets inside a different prison each semester and creates a space where incarcerated persons and law students can engage in conversation about the criminal justice system.[12]

The Maya Angelou School

editThis section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. (July 2023) |

In 1997, Forman cofounded with David Domenici as part of the See Forever Foundation, a comprehensive educational program for teens, which later became the Maya Angelou Public Charter School.[13] Domenici, a Stanford Law graduate and former corporate attorney first pitched his idea for the school to Forman in a D.C. coffee shop in 1995, and they began planning in earnest soon after.[13]

The school was designed to reach troubled children and provide them high-quality education, counseling services, and employment opportunities.[13] Forman thought the program could be incredibly beneficial to some of his clients as a public defender; he wrote in his book: "Most of my clients had struggled in school or dropped out altogether before they were arrested. If a program like [this one] had existed...they might never have become my clients in the first place."[14]

In 1997, Forman took a leave of absence from public defense work to pursue opening the Maya Angelou School.[14] In the fall, with some grant money and teachers hired on, the Maya Angelou Public Charter High School opened with twenty students selected from the court system,[14] all of them either on probation or committed to the Department of Youth and Rehabilitation Services.[15] The students had poor academic records and had often experienced trauma or struggled with mental health.[16] In addition, Forman writes in Locking Up Our Own about ongoing struggles with local police targeting students of the school for searches and arrests.[16]

Despite these difficulties, the school was successful. By September 2004, the Maya Angelou Public Charter High School had grown significantly and opened a second campus location in partnership with the District of Columbia Public Schools.[15]

In the summer of 2007, the Maya Angelou School took over the school inside Oak Hill Detention Center, Washington D.C.'s juvenile prison.[15] The changes enacted by the Maya Angelou School inside the prison were described by a court monitor as contributing to an "extraordinary" turnaround.[8] The same year, the Transition Center was also opened to help young people transition from incarceration by helping them get GEDs and workplace credentials.[15]

Today the Maya Angelou School system includes the Maya Angelou Public Charter High School, the Maya Angelou Young Adult Learning Center (the Transition Center), and the Maya Angelou Academy at New Beginnings.[15]

The Maya Angelou School's mission statement, described as "the Maya Way" on the school's website, is to provide "a comprehensive approach to education that focuses on academic achievement, social and emotional support, and career and college preparation so students are ready for life after Maya."[17]

The school's name was chosen in a contest from an essay written by Sherti Hendrix, a member of the class of 1999, the school's first graduating class.[18]

Bibliography

editForman was part of the 1999 documentary Innocent Until Proven Guilty, which focused on his work as a public defender and with the See Forever Foundation.[19]

Forman has contributed writing about topics such as police brutality, mass incarceration, and the criminal justice system to The Atlantic and The New York Times.

In April 2017, Forman published his first book, Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America.[20] The book examines tough-on-crime policies that were supported in many black communities in the 1970s but are now contributing to mass incarceration. In an interview, Forman stated about the issues addressed in the book: "When we think about our criminal justice system, I don't think we can imagine choices in isolation... And so what I'm trying to argue in the book is that we have to look at this system as a whole, and we have to look at all of its dysfunctions. And only until we do that will we really understand the damage that it's doing to people's lives. Sometimes, some people even say we need more prisons. But they also say, we need more job training. We need more housing. We need better schools. We need funding for drug treatment, for mental health treatment. We need a national gun control policy. We need a Marshall Plan for urban America. We need the federal government to do for black communities what it did for Europe after World War II -- to rebuild, to reinvest, to revitalize. That's the claim. But instead of all of the above, the black community, historically, has gotten one of the above. And the one of the above is law enforcement."[4]

For Locking Up Our Own, Forman received the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.[21] The book was additionally on accolade lists such as the Publishers Weekly Best Books of 2017, The New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice, the GQ Book of the Year as well as the longlist for the National Book Awards and the shortlist for the Inaugural Goddard Riverside Stephan Russo Book Prize for Social Justice.[22]

See also

edit- Mitford family, Forman's maternal grandmother Jessica was one of six famous sisters.

- Black British nobility, Forman's class in Britain

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 8)

References

edit- ^ Forman, James (10 January 2018). "James Forman, Jr. About".

- ^ "James Forman 1967-". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ "The American Philosophical Society Welcomes New Members for 2023".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Gross, Terry (2017-07-17). "How Black Leaders Unwittingly Contributed To The Era Of Mass Incarceration". NPR. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ a b Forman Jr., James (2017). Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 8. ISBN 9780374189976.

- ^ Dalrymple, Helen; Fineberg, Gail (March 2008). "James Forman, Activist: Children Donate Civil Rights Leader's Papers". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ According to a 13 March 1967 letter written at the time of the birth of the couple's first child by Constancia's aunt Deborah, the Duchess of Devonshire, to her sister Nancy Mitford, Romilly and Forman remained unwed "because she is white & would be a handicap to him in his political career (he is the right-hand man of one of the leading Negro politicians from the South) & I suppose that is rather insulting ..." Shortly afterward, Romilly's mother wrote to Nancy Mitford on 6 April 1967, "I don't quite fathom why she doesn't get married (as the babe's father, Jim Foreman [sic], and her [sic] have been living together for ages); but she seems happy with her rum lot, so that's a comfort." The full text of the letters and other correspondence regarding Forman and Romilly's relationship and the births of their children appear in Charlotte Mosley, editor, The Mitfords: Letters between Six Sisters (London: Fourth Estate, 2007; pp. 485-486, 488).

- ^ a b c d e "James Forman Jr". Yale Law School. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ a b c Siegal, Robert (2017-04-18). ""Locking Up Our Own" Details the Mass Incarceration of Black Men". NPR. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ^ Forman Jr., James (2017). Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 7. ISBN 9780374189976.

- ^ Forman Jr., James (2017). Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 121. ISBN 9780374189976.

- ^ "Studying Criminal Justice from the Inside Out". law.yale.edu. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- ^ a b c Forman, Jr., James (2017). Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 151. ISBN 9780374189976.

- ^ a b c Forman, Jr., James (2017). Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 152. ISBN 9780374189976.

- ^ a b c d e "Our Beginnings". See Forever Foundation. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Forman, Jr., James (2017). Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 153. ISBN 9780374189976.

- ^ "Mission". See Forever Foundation. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ "Our Namesake". See Forever Foundation. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ Bell-Russel, Danna. "Innocent Until Proven Guilty: James Forman, Jr., Public Defender". Educational Movie Reviews Online. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ Senior, Jennifer (2017-04-11). ""Locking Up Our Own," What Led to the Mass Incarceration of Black Men". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ^ "Four Yalies win Pulitzer Prize; finalists include professor, alumni". YaleNews. 2018-04-16. Retrieved 2021-04-05.

- ^ "Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America". Macmillan Publishers. Retrieved January 14, 2022.