James Mars (March 3, 1790 – May 27, 1880)[1] was an American slave narrative author and political activist. Born into slavery in Canaan, Connecticut, he gained his freedom in 1811. In 1864, he published his memoir A Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut, Written by Himself—a notable example of the slave narrative genre.[2][3] His grave is a stop on the Connecticut Freedom Trail.[4] In 2021, Governor Ned Lamont declared May 1 to be James Mars Day in Connecticut.[5]

James Mars | |

|---|---|

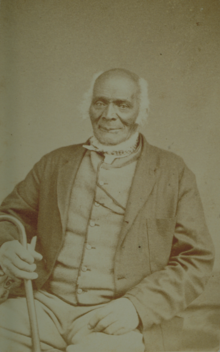

Mars in 1870 | |

| Born | March 3, 1790 Canaan, Connecticut, US |

| Died | May 27, 1880 (aged 90) Ashley Falls, Massachusetts, US |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Autobiography, slave narrative |

| Notable works | A Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut |

Early life and emancipation

editMars was born into slavery in Canaan, Connecticut. His parents, Jupiter and Fanny Mars, were enslaved persons who were owned by the Reverend Amos Thompson, Canaan's Congregational minister, and by Thompson's Virginia-born wife. Jupiter Mars fought in the American Revolution. James's sister, Elizabeth, would spend 34 years as a missionary in Liberia.[6]

In 1784, Connecticut had enacted a gradual emancipation law that freed any enslaved person born in the state on or after March 1, 1784, once the person reached a given age (in Mars's case, the age of 25). However, Thompson attempted to bypass the emancipation law by moving to Virginia, a slave state, and forcing James and his brother, sister, and parents to accompany him. The Mars family instead fled to neighboring Norfolk, Connecticut, and took refuge with white abolitionists, who kept them hidden and safe, moving from place to place, while Thompson and his agents attempted to recapture the fugitives.[1][7]

By September 1798, Thompson struck a deal with the Mars family through intermediaries. As part of the deal, James Mars and his brother agreed to work as slaves in Norfolk until they turned 25. Their parents and sister would be manumitted immediately. James's new captor, a man named Munger, proved a harsh taskmaster. In 1811, Mars paid $90 (~$1,648 in 2023) to buy out his remaining years of servitude.[8] He later reconciled with his captors and cared for the ailing Mr. Munger and his daughter until both died.[9][7]

Activist years

editMars became a leader in New England's freedmen community and in African American reform movements for temperance and enfranchisement. During the 1830s, he worked in a dry goods store in Hartford, Connecticut, where he helped found the Talcott Street Church, in which he served as deacon alongside minister James W. C. Pennington.[2] Mars was a principal in the 1837 landmark case Jackson v. Bulloch, in which the Connecticut Supreme Court freed a fugitive enslaved woman, Nancy Jackson, after she had lived two years in Connecticut with her Georgia captor, James Bulloch. Mars also raised funds for the legal defense of the passengers of La Amistad.[1][2][8] By 1840, he was serving on the board of the mostly white Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society.[10]

Later life

editMars married in the early 1830s. By the time they departed Hartford, he and his wife had had eight children, one of whom died in infancy. Circa 1845, the family moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he lived for twenty years, purchased land, farmed, and continued to participate in Black reform and antislavery movements.[1] Three of his sons fought for the Union in the Civil War.[7]

As an impoverished elderly man, Mars returned to Norfolk and published The Life of James Mars: A Slave Bought and Sold in Connecticut (Hartford: Case, Lockwood & Company, 1864).[1] The pamphlet-length book went through at least six editions, including a 1868 edition that included more details of his later life.[7] Mars explained that he wrote his memoirs because "some told me that they did not know that slavery was ever allowed in Connecticut, and some affirm that it never did exist in the State."[9]

In August 1879, Mars was granted a pension by the State of Connecticut.[11] He died less than a year later in Ashley Falls, Massachusetts. He was interred in the Center Cemetery in Norfolk.[4]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Hinks, Peter (2006), "Mars, James", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.44876, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1

- ^ a b c White, David O. (2004). "The Real Life of James Mars". Connecticut History Review. 43 (1): 28–46. doi:10.2307/44369902. ISSN 0884-7177. JSTOR 44369902. S2CID 254480229.

- ^ Bontemps, Arna, ed. (1971). Five Black Lives: The Autobiographies of Venture Smith, James Mars, William Grimes, the Rev. G.W. Offley, [and] James L. Smith. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-4036-2. OCLC 159550.

- ^ a b "List of Sites - James Mars Gravesite". Connecticut Freedom Trail. Archived from the original on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- ^ "Salisbury will honor former enslaved man James Mars". The Register Citizen. 2021-04-26. Retrieved 2022-02-01.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Conrad, Robert J. (1996-06-16). "Slave's Narrative Tells a History of Humanity". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ a b c d Hutchins, Zachary (n.d.). "Summary of Life of James Mars, A Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Written by Himself". Documenting the American South. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ a b Menschel, David (2001). "Abolition without Deliverance: The Law of Connecticut Slavery 1784-1848". Yale Law Journal. 111 (1): 183–222. doi:10.2307/797518. ISSN 0044-0094. JSTOR 797518.

- ^ a b Hinks, Peter P. (2015-02-28). "James Mars' Words Illuminate the Cruelty of Slavery in New England". Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ Beeching, Barbara J. (2016). Hopes and Expectations: The Origins of the Black Middle Class in Hartford. SUNY Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-1-4384-6165-6.

- ^ "A Connecticut Slave". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. 1879-08-25. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

External links

edit- Life of James Mars, A Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut - Full text via the Library of Congress