James Scott Skinner (5 August 1843 – 17 March 1927) was a Scottish dancing master, violinist, fiddler and composer. He is considered to be one of the most influential fiddlers in Scottish traditional music, and was known as "the Strathspey King".

Early years

editSkinner was born on 5 August 1843 in Arbeadie in the parish of Banchory, Aberdeenshire, the youngest of six children. His father William Skinner was a dancing teacher. His mother, Mary Skinner (née Agnew) originally came from Strathdon. His father died in 1845. When his mother remarried seven years later, he moved to Aberdeen where he lived with his sister Annie and attended Connell's School.[1]

His elder brother Alexander "Sandy" Forbes Skinner gave him lessons in violin and cello, and he started playing at local dances with local fiddler Peter Milne.[1][2]

Career

editThree years later he left to join Dr Mark's Little Men, a travelling orchestra. This involved spending six years intensive training at their headquarters in Manchester. It also involved touring round the UK. The orchestra gave a command performance before Queen Victoria at Buckingham on 10 February 1858. Skinner attributed his own later success to meeting Charles Rougier in Manchester, who taught him to play Beethoven and other classical masters. Finally he took a year's dancing tuition from William Scott. Skinner could now earn his living as a dancing master for the district around Aberdeen.

In 1862 he won a sword-dance competition in Ireland. The following year he won a strathspey and reel competition in Inverness. Gradually he broadened his district of clients until Queen Victoria learned of his reputation. She requested him to teach callisthenics and dancing to the royal household at Balmoral. In 1868 he had 125 pupils there. In the same year his first collection of compositions was published. By 1870 he had married and was soon living in Elgin. For twelve years he continued as a dancing master and violinist. He gave virtuoso concerts, with his adopted daughter joining him as a pianist. In 1881 his wife became seriously ill and died a couple of years later. For the next ten years he spent little time in any one place. The 1880s did see three more collections of tunes published. In 1893 he toured the United States with Willie MacLennan, the celebrated bagpiper and dancer.

After returning to Scotland he virtually gave up dancing and concentrated on the fiddle. In 1897 he remarried and wrote some of his best work. In 1899 he made his first cylinder recordings. In 1903, he wrote one of his best known tunes, Hector the Hero, a lament for Scottish Major-General Hector MacDonald, a friend of Skinner's who committed suicide following accusations of homosexuality. In 1904, Skinner published The Harp & Claymore Collection, his biggest collection of music, edited by Gavin Greig.[3]

In the period from 1906 to 1909 he lived a settled life in Monikie but had so little money that he could not afford to publish his work. He sent manuscripts to friends who copied them out and played them to create a market. Those precious scraps of paper, the backs of envelopes and hand-bills are now in museums. Skinner frequently used the word "genius" to describe himself. This might explain the fact that in 1909 his wife "resigned" and moved to Rhodesia. He threw himself into another round of concert tours. Several of his 1910 recordings for Columbia in London are available on a CD on the Temple label. These include traditional tunes as well as his own works, presenting a unique window into early twentieth century fiddle playing and probably back to the 1850s.

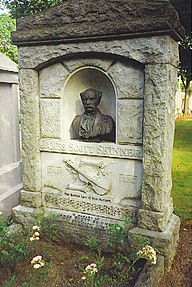

In 1925 he was still top of the bill on five tours of the UK. Skinner entered a reel and jig competition in the United States in 1926. He immediately had musical differences with the pianist and strode off stage without completing his test pieces. He died on 17 March 1927 without giving another public performance. His body was buried in Aberdeen, where his marble memorial gravestone, by the artist and sculptor Frederick William George, was unveiled by Sir Harry Lauder.[4]

Publications

editOver 600 of his compositions were published, among the best known being "The Bonnie Lass of Bon Accord," "Cradle Song," "Bovaglie's Plaid," "The Music o' Spey," and "Hector the Hero." He made over 80 recordings.

References

edit- ^ a b "Biography – The Music of James Scott Skinner". abdn.ac.uk. University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "J. Scott Skinner". Scottish Traditional Music Hall of Fame. Hands Up For Trad. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Ballantyne, Pat The Harp & Claymore Collection Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 January 2009

- ^ The Lost Works of Frederick William George. Campbell Wilson. 2009. p. Unnumbered.

- Alburger, Mary Anne (1983), Scottish Fiddlers And Their Music, Victor Gollancz Ltd., ISBN 0-575-03174-3.

- Emmerson, George S. (1971), Rantin' Pipe And Tremblin' String, McGill-Queen's University Press, ISBN 0-7735-0116-9.

External links

edit- The Music of James Scott Skinner (Aberdeen University)

- Visit Banchory – Birthplace of Scott Skinner

- James Scott Skinner: The Miller O'Hirn Collection University of Glasgow (library), Book of the Month June 2000 by Lynne Dent