Knowing (stylized as KNOW1NG) is a 2009 American science fiction thriller film[4] directed and co-produced by Alex Proyas and starring Nicolas Cage. The film, conceived and co-written by Ryne Douglas Pearson, was originally attached to a number of directors under Columbia Pictures, but it was placed in turnaround and eventually picked up by Escape Artists. Production was financially backed by Summit Entertainment. Knowing was filmed in Docklands Studios Melbourne, Australia, using various locations to represent the film's Boston-area setting. The film centers on the discovery of a strange paper filled with numbers and the possibility that they somehow predict the details of various disasters.

| Knowing | |

|---|---|

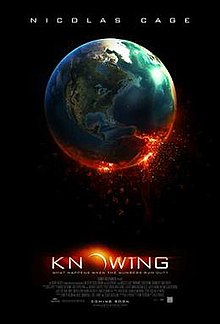

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alex Proyas |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Ryne Douglas Pearson |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Simon Duggan |

| Edited by | Richard Learoyd |

| Music by | Marco Beltrami |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Summit Entertainment (United States) Contender Entertainment (United Kingdom)[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 121 minutes |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $186.5 million[3] |

The film was released on March 20, 2009, in the United States. The DVD and Blu-ray media were released on July 7. Knowing grossed $186.5 million at the worldwide box office, plus $27.7 million with home video sales, against an average production budget of $50 million. It met with mixed reviews, with praise for the acting performances, visual style and atmosphere, but criticism over some implausibilities and the ending.

Plot

editIn 1959, a Lexington, Massachusetts, elementary school celebrates its opening with a competition in which students draw what they believe will happen in the future. All the children create visual works except for Lucinda Embry. Guided by whispering voices, Lucinda fills her paper with a series of numbers. Before she can write the final numbers, the allotted time for the task expires, and the teacher collects the students' drawings. The following day, Lucinda engraves the remaining numbers into a closet door with her fingernails. The works are stored in a time capsule and opened 50 years later when the current class distributes the drawings among the students. Lucinda's paper is given to Caleb Koestler, the 9-year-old son of widowed MIT astrophysics professor John Koestler.

John discovers that Lucinda's numbers are dates, death tolls, and geographical coordinates of major disasters over the past 50 years, including the Oklahoma City bombing, September 11 attacks, and Hurricane Katrina, as well as three more yet to happen. In the following days, John witnesses two of the three final events in person: a plane crash and a New York City Subway derailment caused by a faulty siding. John becomes convinced that his family has a significant role in these incidents: his wife died in one of the earlier events, while Caleb was the one to receive Lucinda's message. Meanwhile, Caleb begins hearing the same whispering voices as Lucinda.

John locates Lucinda's daughter Diana and her granddaughter Abby to help prevent the last event. Diana becomes suspicious but eventually goes with John to Lucinda's abandoned mobile home, where they find a copy of Matthäus Merian's engraving of Ezekiel's "chariot vision", in which a great sun is represented. They also discover that the final two digits of Lucinda's message are not numbers but two reversed letter E's, matching the message left by Lucinda under her bed: "Everyone Else," implying an extinction-level event. During the search, Caleb and Abby, who were left asleep in the car, have an encounter with the beings who are the source of the whispers. Diana tells John that her mother had always told her the date she would die. He also visits Lucinda's teacher, who despite showing signs of Alzheimer's disease, tells him of the scratching on the door left by Lucinda.

The next day, Abby colors in the sun on the engraving, which gives John a revelation. He rushes to the MIT observatory and learns that a massive solar flare with the potential to destroy all life will strike the Earth on the last date indicated by the message. As Diana and Abby prepare to take refuge in nearby caves, John goes to the school and finds the door on which Lucinda engraved the final numbers. He identifies them as coordinates of a place where he believes they may find salvation from the solar flare. The skeptical and hysterical Diana loads Caleb and Abby into her car and flees for the caves.

At a gas station, the whispering beings steal Diana's car with Caleb and Abby inside. Diana pursues them but is killed in a crash. The beings take Caleb and Abby to Lucinda's mobile home, where John encounters them shortly thereafter. The beings, acting as extraterrestrial angels, are leading children to safety on interstellar arks. John is told he cannot go with them because he never heard the whispering, so he convinces Caleb to leave with Abby. The two are taken away by the being, and the ark, along with many others, leaves the Earth.

The following morning, John decides to be with his family when the flare strikes and drives to his parents' house, where he reconciles with his estranged father. The solar flare then strikes, vaporizing New York City, and then destroying the Earth. Meanwhile, the ark deposits Caleb and Abby on another world resembling an earthly paradise and departs, as do other arks. The two run through a field towards a large white mysterious tree resembling the tree of life.

Cast

edit- Nicolas Cage as John Koestler

- Rose Byrne as Diana

- Chandler Canterbury as Caleb Koestler

- Joshua Long as young Caleb

- Ben Mendelsohn as Phil Beckman

- Lara Robinson as Abby / Lucinda

- D.G. Maloney as The Stranger

- Nadia Townsend as Grace

- Alan Hopgood as Reverend Koestler

- Adrienne Pickering as Allison Koestler

- Danielle Carter as Miss Taylor (1959)

- Alethea McGrath as Miss Taylor (2009)

- Tamara Donnellan as Lucinda's mother

- Travis Waite as Lucinda's father

- Liam Hemsworth as Spencer

- Gareth Yuen as Donald

- Ra Chapman as Jessica

- Benita Collings as John's mother

- Terry Camilleri as Cashier

Production

editDevelopment

editIn 2001, novelist Ryne Douglas Pearson approached producers Todd Black and Jason Blumenthal with his idea for a film, where a time capsule from the 1950s is opened revealing fulfilled prophecies, of which the last one ended with 'EE' – "everyone else". The producers liked the concept and bought his script.[5] The project was set up at Columbia Pictures. Both Rod Lurie and Richard Kelly were attached as directors, but the film eventually went into turnaround. The project was picked up by the production company Escape Artists, and the script was rewritten by Stiles White and Juliet Snowden. Director Alex Proyas was attached to direct the project in February 2005.[6] Proyas said the aspect that attracted him the most was the "very different script" and the notion of people seeing the future and "how it [shapes] their lives".[5] Summit Entertainment took on the responsibility to fully finance and distribute the film. Proyas and Stuart Hazeldine rewrote the draft for production,[7] which began on March 25, 2008 in Melbourne, Australia.[8] The director hoped to emulate The Exorcist in melding "realism with a fantastical premise".[9]

Filming

editThe film is set primarily in the town of Lexington with some scenes set in the nearby cities of Cambridge and Boston. However, it was shot in Australia, where director Proyas resides.[5] Locations included the Geelong Ring Road; the Melbourne Museum; "Cooinda", a residence in Mount Macedon which was the location for all of the "home and garden" scenes; and Collins Street in Melbourne.[2] Filming also took place at Camberwell High School, which was converted into the fictional William Dawes Elementary, located in 1959 Lexington.[10][11] Interior shots took place at the Australian Synchrotron to represent an observatory.[12][13] Filming also took place at the Haystack Observatory in Westford, Massachusetts.[14] In addition to practical locations, filming also took place at the Melbourne Central City Studios in Docklands.[15] The plane crash, which was mostly shown in one take in the film, was done in a nearly-finished freeway outside Melbourne, the Geelong Ring Road, mixing practical effects and pieces of a plane with computer-generated elements. The scenographic rain led to the usage of a new gel for the flames so the fire would not be put out, and semi-permanent make-up to make them last the long shooting hours.[5] The solar flare destruction sequence is set in New York City, showing notable landmarks such as the Metlife Building, Times Square and the Empire State Building being obliterated as the flare spreads across the Earth's surface, destroying everything in its path.[16]

Proyas used a Red One 4K digital camera. He sought to capture a gritty and realistic look to the film, and his approach involved a continuous two-minute scene in which Cage's character sees a plane crash and attempts to rescue passengers. The scene was an arduous task, taking two days to set up and two days to shoot. Proyas explained the goal, "I did that specifically to not let the artifice of visual effects and all the cuts and stuff we can do, get in the way of the emotion of the scene."[17]

Soundtrack

edit| Knowing: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | March 24, 2009 |

| Genre | Film score |

| Length | 65:39 |

| Label | Varèse Sarabande |

The music for the film was written by Marco Beltrami, but also features classical works such as Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven) - Allegretto,[18] which is played without any accompanying sound effects in the final Boston disaster scene of the film.[19] Beltrami released the soundtrack as a CD with 22 tracks.[20]

Reception

editBox office

editKnowing was released in 3,332 theaters in the United States and Canada on March 20, 2009, and grossed US$24,604,751 in its opening weekend,[1] placing first at the box office.[21] According to exit polling, 63% of the audience was 25 years old and up and evenly split between genders.[22] On the weekend of March 17, 2009, Knowing ranked first in the international box office, grossing US$9.8 million at 1,711 theatres in ten markets, including first with US$3.55 million in the United Kingdom.[23] The film had grossed US$80 million in the United States and Canada and US$107 million in other territories for a worldwide total of US$186.5 million, plus US$27.7 million with home video sales, against a production budget of US$50 million.[3]

Critical reception

editReview aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a 34% critic rating based upon a sample of 184 critics with an average rating of 4.80/10. The site's consensus: "Knowing has some interesting ideas and a couple good scenes, but it's weighted down by its absurd plot and over-seriousness".[24] Metacritic gave the film a score of 41% based on 27 reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[25]

A. O. Scott of The New York Times gave the film a negative review and wrote, "If your intention is to make a brooding, hauntingly allegorical terror-thriller, it's probably not a good sign when spectacles of mass death and intimations of planetary destruction are met with hoots and giggles ... The draggy, lurching two hours of Knowing will make you long for the end of the world, even as you worry that there will not be time for all your questions to be answered."[26] In the San Francisco Chronicle, Peter Hartlaub called the film "an excitement for fans of Proyas" and "a surprisingly messy effort". He thought Nicolas Cage "borders on ridiculous here, in part because of a script that gives him little to do but freak out or act depressed".[27]

Writing for The Washington Post, Michael O'Sullivan thought the film was "creepy, at least for the first two-thirds or so, in a moderately satisfying, if predictable, way ... But the narrative corner into which this movie... paints itself is a simultaneously brilliant and exciting one. Well before the film neared its by turns dismal and ditzy conclusion, I found myself knowing—yet hardly able to believe—what was about to happen."[28] Betsy Sharkey of the Los Angeles Times found it to be "moody and sometimes ideologically provocative" and added, "Knowing has its grim moments—and by that I mean the sort of cringe- (or laugh-) inducing lines of dialogue that have haunted disaster films through the ages ... So visually arresting are the images that watching a deconstructing airliner or subway train becomes more mesmerising than horrifying."[29]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times was enthusiastic, rating it four stars out of four and writing, "Knowing is among the best science-fiction films I've seen—frightening, suspenseful, intelligent and, when it needs to be, rather awesome."[30] He continued, "With expert and confident storytelling, Proyas strings together events that keep tension at a high pitch all through the film. Even a few quiet, human moments have something coiling beneath. Pluck this movie, and it vibrates."[30] Ebert later listed it as the sixth best film of 2009.

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian suggested Knowing was saved by its ending, concluding that "the film sticks to its apocalyptic guns with a spectacular and thoroughly unexpected finish."[31] Philip French's review in The Observer suggested the premise was "intriguing B-feature apocalypse, determinism versus free will stuff" and that the ending has something for everyone: "A chosen few will apparently be swept away by angels to a better place. If you're a Christian fundamentalist who believes that Armageddon is nigh, you'll have a family hug and wake up to be greeted by St Peter at the Pearly Gates. On the other hand, Darwinists will be gratified to see Gaia and her stellar opposite numbers sock it to an unconcerned mankind."[32] Richard von Busack of Metroactive derided the striking similarity between the film and the Arthur C. Clarke novel Childhood's End.[33]

Accolades

editThe film was nominated at the 8th Visual Effects Society Awards in the category of "Best Single Visual Effect of the Year" for the plane crash sequence.[34]

Home media

editKnowing was released on DVD on July 7, 2009, opening in the United States at No. 1 for the week and selling 773,000 DVD units for US$12.5 million in revenue. In total, 1.4 million DVD units were sold in the United States for a US$21.1 million and US$25 million worldwide. From Blu-ray sales, the film also earned US$1.6 million in the United States and a total of US$2.6 million worldwide. The estimated gross for global domestic video sales is US$27.6 million.[35]

Lawsuit

editOn November 25, 2009, Global Findability filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Summit Entertainment and Escape Artists in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, claiming that a geospatial entity object code was used in the film Knowing which infringed Patent US 7107286 Integrated information processing system for geospatial media.[36][37][38][39] The case was dismissed on January 10, 2011.[40]

Scientific accuracy

editRegarding the film's grounding in science, director Alex Proyas said at a press conference: "The science was important. I wanted to make the movie credible. So of course we researched as much as we could and tried to give it as much authenticity as we could".[41]

Several writers criticized the treatment of science in the film. Ian O'Neill of Discovery News criticized the film's solar flare plot line, pointing out that the most powerful solar flares could never incinerate Earthly cities.[42] Erin McCarthy of Popular Mechanics calls attention to the film's confusion of numerology, the occult's study of how numbers like dates of birth influence human affairs, with the ability of science to describe the world mathematically to make predictions about things like weather or create technology like cell phones.[41] Steve Biodrowski of Cinefantastique refers to the film's approach as disappointingly "pseudo-scientific". He writes, "Cage plays an astronomer, and his discussions with a colleague hint that the film may actually grapple with the question of predicting the future, perhaps even offer a plausible theory. Unfortunately, this approach is abandoned as Koestler pursues the disasters, and the film eventually moves into a mystical approach".[43]

Asked about his research for the role, Nicolas Cage stated: "I grew up with a professor, so that was all the research I ever needed". His father, August Coppola, was a professor of comparative literature at Cal State Long Beach.[44]

See also

edit- 2012 (film) – 2009 film by Roland Emmerich

- 20th Century Boys – Japanese manga series

- Graphomania – Obsessive impulse to write

References

edit- ^ a b "Knowing (2009)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Ziffer, Daniel (April 7, 2008). "Night at the museum". The Age. Australia. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Knowing". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- ^ "Knowing (2009) - Alex Proyas | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related". AllMovie.

- ^ a b c d Knowing All: The Making of a Futuristic Thriller. Knowing DVD.

- ^ Laporte, Nicole (February 16, 2005). "Proyas digs Knowing gig". Variety. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (December 10, 2007). "Cage to star in Proyas' Knowing". Variety. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Byrne Set for Sci-Fi Thriller Knowing". VFXWorld.com. Animation World Network. March 4, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Vejvoda, Jim (July 24, 2008). "SDCC 08: Knowing When to Push". IGN. Archived from the original on July 27, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ Nye, Doug (July 7, 2009). "Grumpy Old Men,' Knowing' top short list of new Blu-ray releases". Victoria Advocate. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ^ Metlikovec, Jane (March 20, 2008). "Nicolas Cage goes back to school". Herald Sun. Australia. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Bernecich, Adrian (October 28, 2008). "Powerhouse for research". Waverly Gazette.

- ^ "International Film Shot at Australian Synchrotron" (PDF). Lightspeed. Australian Synchrotron Company, Ltd. April 1, 2008. p. 1. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Minch, Jack (September 23, 2008). "Hollywood coming to Westford". The Sun.

- ^ Wigney, James (April 27, 2008). "Nicolas's golden cage an empty shell". Herald Sun. Australia. Archived from the original on April 28, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "Knowing (2009)". onthesetofnewyork.com. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Minnick, Remy (August 12, 2008). "Alex Proyas: And Knowing Is Half The Battle". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ "Knowing (2009) Soundtrack". Soundtrack.Net. Autotelics, LLC. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ "KNOWING-The End of the World". YouTube. December 13, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Knowing (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". Varèse Sarabande. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (March 22, 2009). "Knowing tops weekend box office". Variety. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ Gray, Brandon (March 23, 2009). "Weekend Report: Knowing Digs Up the Digits". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ^ McNary, Dave (March 29, 2009). "Knowing tops foreign box office". Variety. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ "Knowing (2009)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "Knowing Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (March 20, 2009). "Extinction Looms! Stop the Aliens!". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (March 20, 2009). "Movie review: Knowing funny for a thriller". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Michael (March 20, 2009). "Few Surprises in Knowing". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ Sharkey, Betsy (March 20, 2009). "'Knowing,' but still in the dark". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (March 22, 2009). "Love and hate and "Knowing" -- or, do wings have angels?". rogerebert.suntimes.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (March 27, 2009). "Film review: Knowing". The Guardian. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ French, Philip (March 29, 2009). "Film review: Knowing". The Observer. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ von Busack, Richard (March 25, 2009). "Tribulation 99. 'Knowing': Bad day with black rocks". Metroactive. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ "8th Annual VES Awards". visual effects society. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "Knowing (2009) - Financial Information (Video sales)". The Numbers. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ "Complaint" (PDF). Courthouse News. November 30, 2009. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (December 2, 2009). "Can a science-fiction movie infringe a tech patent?". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Crouch, Dennis (December 8, 2009). "Patents and the Movie Industry: Stopping Nicholas Cage". PatentlyO blog. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ "GLOBAL FINDABILITY, INC. v. SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT, LLC et al". Justia. November 25, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "Case Docket for No. 09-2247". Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Erin (September 30, 2009). "Knowing Blends Science Fact with Fiction (Beware: Spoilers!)". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ O'Neill, Ian (August 23, 2009). ""Knowing" How Solar Flares Don't Work". AstroEngine.com. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Biodrowski, Steve (March 20, 2009). "Knowing – Science Fiction Film Review". Cinefantastique. Archived from the original on December 10, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "August Coppola, arts educator, dies at 75". San Francisco Chronicle. November 4, 2009.

External links

edit- KNOW1NG.COM

- Knowing at IMDb

- Knowing at AllMovie