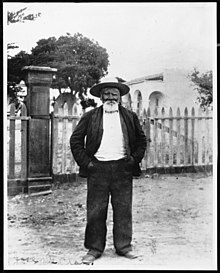

José de Grácia Cruz (c. 1848 – 1924) was a Acjachemen man who was born in 1848 at Mission San Juan Capistrano.[1] He was known for his work as a bell ringer at the mission, as an artisan, a flutist in a native orchestra that would play at the mission, a sheep shearer, and for his knowledge of the Juaneño language and village sites, including Puvunga.[2][3][4] He was also the source of the story of the mission's swallows in St. John O'Sullivan's Capistrano Nights (1930).[3] He was referred to locally as "Acǘ,"[4] a nickname that was reportedly given to him as a child by his parents.[5]

José de Grácia Cruz | |

|---|---|

José de Grácia Cruz in 1909 (born 1840s), Juaneño (Acjachemen) bell ringer at Mission San Juan Capistrano. | |

| Born | 1848 |

| Died | 1924 |

| Other names | Acǘ |

| Occupation(s) | Bell ringer, artisan, sheep shearer, flutist |

| Known for | Knowledge of the Juaneño language, Mission San Juan Capistrano, and Acjachemen village sites |

Life

editGracia Cruz was born at Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1848. He lived his whole life in the town and had relatives in the native village of Temecula. His father, Lázaro, was a bell ringer at the Mission, and he inherited this position from him. His father taught him how to ring in regard to various events, including for feast days and other public occasions.[1][5]

In December 1907, Alfred Kroeber recorded that "it was found possible to spend a short time with an elderly Juaneño called Jose de Gracia Cruz, born at the Mission and living almost within hail of it and the present railroad station. The vocabulary obtained from him is obtained below."[2] The Juaneño language vocabulary provided by Grácia Cruz included numbers, family members, relationships, body parts, natural phenomena, animals, actions, and more.[2]

Later in his life, he was asked by St. John O'Sullivan why he had not become wealthy from his work as a sheep shearer, leading a sheep shearing band from Rincon and Pala. Grácia Cruz responded: "It is not good for an Indian to be rich, padre. There are not any rich Indians. It would not do, padre. A rich Indian is proud; he won't take orders from you or any American; but when all his money is gone... he is very humble." Historian Lisbeth Haas argued that Grácia Cruz used double meaning in this reply, stating that "the irony escaped the priest" who saw Gracia Cruz as a "child of the mission."[1]

In Capistrano Nights (1930), Grácia Cruz is noted as having replied to the question of "How are you?" as "Very sad, patron. Because, patron, I am very old; also I am very poor, for God does not help me. I am now working these fifty years, and I have no money."[5] After many years of his work throughout his life, Grácia Cruz died in 1924.[3] His nephew, Paul Arbiso, became the bell ringer at the mission some time after his death.[1]

Legacy

editThe publication of O'Sullivan's Capistrano Nights (1930) memorialized Grácia Cruz's life in print, which was reprinted numerous times following its original publication.[5]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Haas, Lisbeth (1996). Conquests and historical identities in California, 1769-1936 ([Pbk. ed., 1996] ed.). Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. pp. 110, 134. ISBN 978-0-520-91844-3. OCLC 45732484.

- ^ a b c Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1910). A Mission Record of the California Indians: From a Manuscript in the Bancroft Library, Volume 8, Issues 1-6. The University Press. pp. 247–250.

- ^ a b c Hallan-Gibson, Pamela; Tryon, Don; Tryon, Mary Ellen; et al. (San Juan Capistrano Historical Society) (2005). San Juan Capistrano. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439630983.

- ^ a b Loewe, Ronald (2016). Of sacred lands and strip malls : the battle for Puvungna. Lanham, MD. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7591-2162-1. OCLC 950751182.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Capistrano Nights. Wildside Press. 2007 [1930]. ISBN 9781434489722.